This section is of particular relevance if you have not yet selected a research topic and do not know where to start. If you have already selected your topic or question, go to the next section.

Most research in the humanities revolves around four Ps:

- people;

- problems;

- programmes;

- phenomena.

In fact, a closer look at any academic or occupational field will show that most research revolves around these four Ps. The emphasis on a particular ‘P’ may vary from study to study but generally, in practice, most research studies are based upon at least a combination of two Ps. You may select a group of individuals (a group of individuals — or a community as such — ‘people’), to examine the existence of certain issues or problems relating to their lives, to ascertain their attitude towards an issue (‘problem’), to establish the existence of a regularity (‘phenomenon’) or to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention (‘programme’). Your focus may be the study of an issue, an association or a phenomenon per se; for example, the relationship between unemployment and street crime, smoking and cancer, or fertility and mortality, which is done on the basis of information collected from individuals, groups, communities or organisations. The emphasis in these studies is on exploring, discovering or establishing associations or causation. Similarly, you can study different aspects of a programme: its effectiveness, its structure, the need for it, consumers’ satisfaction with it, and so on. In order to ascertain these you collect information from people.

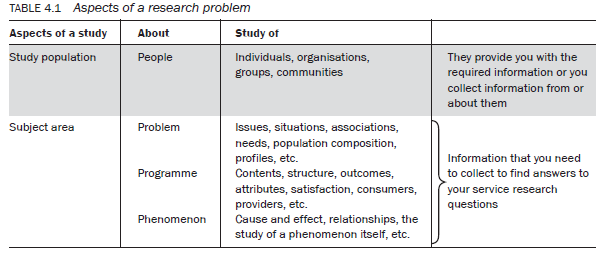

Every research study has two aspects: the people provide you with the ‘study population’, whereas the other three Ps furnish the ‘subject areas’. Your study population — individuals, groups and communities — is the people from whom the information is collected.Your subject area is a problem, programme or phenomenon about which the information is collected. This is outlined further in Table 4.1, which shows the aspects of a research problem.

You can study a problem, a programme or a phenomenon in any academic field or from any professional perspective. For example, you can measure the effectiveness of a programme in the field of health, education, social work, industrial management, public health, nursing, health promotion or welfare, or you can look at a problem from a health, business or welfare perspective. Similarly you can gauge consumers’ opinions about any aspect of a programme in the above fields.

Examine your own academic discipline or professional field in the context of the four Ps in order to identify anything that looks interesting. For example, if you are a student in the health

field there are an enormous number of issues, situations and associations within each subfield of health that you could examine. Issues relating to the spread of a disease, drug rehabilitation, an immunisation programme, the effectiveness of a treatment, the extent of consumers’ satisfaction or issues concerning a particular health programme can all provide you with a range of research problems. Similarly, in education there are several issues: students’ satisfaction with a teacher, attributes of a good teacher, the impact of the home environment on the educational achievement of students, and the supervisory needs of postgraduate students in higher education. Any other academic or occupational field can similarly be dissected into subfields and examined for a potential research problem. Most fields lend themselves to the above categorisation even though specific problems and programmes vary markedly from field to field.

The concept of 4Ps is applicable to both quantitative and qualitative research though the main difference at this stage is the extent of their specificity, dissection, precision and focus. In qualitative research these attributes are deliberately kept very loose so that you can explore more as you go along, in case you find something of relevance. You do not bind yourself with constraints that would put limits on your ability to explore. There is a separate section on ‘Formulating a research problem in qualitative research’ later in the chapter, which provides further guidance on the process.

Source: Kumar Ranjit (2012), Research methodology: a step-by-step guide for beginners, SAGE Publications Ltd; Third edition.

Hi there i am kavin, its my first time to commenting

anywhere, when i read this article i thought i could also make comment due to this sensible article.

I’m not that much of a internet reader to be honest but your

blogs really nice, keep it up! I’ll go ahead and bookmark your website to come back in the future.

Cheers

I am not sure where you are getting your info, but good topic.

I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more.

Thanks for excellent information I was looking for this info

for my mission.

Good answers in return of this matter with solid arguments and describing all about that.