Although not everyone agrees precisely on the components of a business model, many agree that a successful business model has a common set of at- tributes. These attributes are often laid out in a visual framework or template so it is easy to see the individual parts and their interrelationships. One widely- used framework is the Business Model Canvas, popularized by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur in their book, Business Model Generation.11 The Business Model Canvas consists of nine basic parts that show the logic of how a firm intends to create, deliver, and capture value for its stakeholders. You can view the Business Model Canvas via a simple Google search.

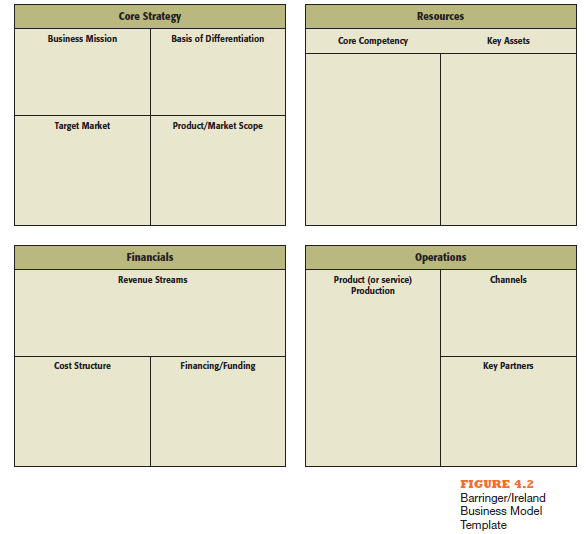

The business model framework used here, the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template, is shown in Figure 4.2. It is slightly more comprehensive than the Business Model Canvas in that it consists of 4 major categories and 12 individual parts. The 12 parts make up a firm’s business model. The job of the entrepreneur, or team of entrepreneurs, is to configure their firm’s business model in a manner that produces a viable and exciting business. The Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template is a tool that allows an entrepreneur to describe, project, revise, and pivot a business model until all 12 parts are decided upon. Appendix 4.1 contains an expanded version of the Barringer/Ireland Template shown here. The 12 parts are spread out, which provides space for ideas to be recorded, scratched out, and recorded again as ideas morph and change. Feel free to copy and use the template to help formulate the business model for an individual firm.

Next, we discuss each of the 4 categories and the 12 individual elements of a firm’s business model. We will refer frequently to Figure 4.2 throughout the discussion.

1. Core Strategy

The first component of a business model is core strategy. A core strategy describes how the firm plans to compete relative to its competitors.12 The pri- mary elements of core strategy are: business mission, basis of differentiation, target market, and product/market scope.

Business Mission A business’s mission or mission statement describes why it exists and what its business model is supposed to accomplish.13 If carefully written and used properly, a mission statement can articulate a busi- ness’s overarching priorities and act as its financial and moral compass. A firm’s mission is the first box that should be completed in the business model template. A well-written mission statement is something that a business can continually refer back to as it makes important decisions in other elements of its business model.

At a 50,000-foot level, a mission statement indicates how a firm intends to create value for stakeholders. For example, Zynga’s mission is “Connecting the world through games.” Zynga is a producer of social games, such as FarmVille and Texas HoldEm Poker, which can be played through its website and social networking platforms such as Facebook and Google+. Although Zynga’s mission statement is short and to the point, it provides direction for how the other elements of its business model should be configured. The company will focus on games, as opposed to other business pursuits, and its games will be social, meaning that they will be designed to be played with other people. The remaining 11 parts of Zynga’s business model should sup- port these basic premises.

There are several rules of thumb for writing mission statements. A business’s mission statement should:

■ Define its “reason for being”

■ Describe what makes the company different

■ Be risky and challenging but achievable

■ Use a tone that represents the company’s culture and values

■ Convey passion and stick in the mind of the reader

■ Be honest and not claim to be something that the company “isn’t”

Basis of Differentiation It’s important that a business clearly articulate the points that differentiate its product or service from competitors.14 This is akin to what some authors refer to as a company’s value proposition. A company’s basis of differentiation is what causes consumers to pick one company’s products over another’s.15 It is what solves a problem or satisfies a customer need.

When completing the basis for differentiation portion of the Barringer/ Ireland Business Model Template, it’s best to limit the description to two to three points. Also, make sure that the value of the points is easy to see and understand. For example, ZUCA (www.zuca.com) is a backpack on rollers. It was designed by Laura Udall as an alternative to traditional backpacks when her fourth-grade daughter complained daily that her back hurt from carrying her backpack. The ZUCA has two distinct points of differentiation: It relieves back pain by putting backpacks on rollers and it is sturdy enough for either a child or adult to sit on. The company’s website frequently features photos of kids sitting on the ZUCA seat, which anyone could imagine might be handy for kids waiting for the school bus. These are points of differentiation that are easy to grasp and remember. They are the reasons that some parents will choose ZUCA’s product and solution over others.

Making certain that your points of differentiation refer to benefits rather than features is another important point to remember when determining a firm’s basis of differentiation. Points of differentiation that focus on features, such as the technical merits of a product, are less compelling than those that focus on benefits, which is what a product can do. For example, when Laura Udall introduced the ZUCA, she could have focused on the features of the product and listed its points of differentiation as follows: (1) is pulled like a suitcase rather than worn on the back, (2) includes a sturdy aluminum frame, and (3) is available in six colors. While features are nice, they typically don’t entice someone to buy a product. A better approach for Udall would have been to focus on the benefits of the product: (1) relieves back pain by putting back- packs on rollers, (2) is sturdy enough for either an adult or child to sit on, and (3) strikes the ideal balance between functionality and “cool” for kids. This set of points focuses on benefits. It tells parents how buying the product will en- hance their son or daughter’s life.

Target Market The identification of the target market in which the firm will compete is extremely important.16 As explained in Chapter 3, a target market is a place within a larger market segment that represents a narrower group of customers with similar interests.17 Most new businesses do not start by sell- ing to broad markets. Instead, most start by identifying an emerging or under- served niche within a larger market.18

A firm’s target market should be made explicit on the business model template. Her Campus’s target market is active college females. Zynga’s tar- get market is online game enthusiasts. A target market can be based on any relevant variable, as long as it identifies for a firm the group of like-minded customers that it will try to appeal to. For example, Hayley Barna and Katia Beauchamp, the founders of Birchbox, wrote the following about their com- pany’s target market:

From the start, we’ve always said that our target market isn’t a specific demo- graphic, but instead a psychographic—we believe that Birchbox appeals to women of all ages and backgrounds as long as they are excited to try new things and learn through discovery.19

This type of awareness of a firm’s intended market, and the people who are the most likely to respond positively to a firm’s product or service, is helpful in build- ing out all the elements of a firm’s business model. For example, targeting women of all ages and backgrounds who are excited to try new things and learn through discovery requires a certain set of core competencies (we define core competen- cies in the next section). It requires identifying and hiring people who have the ability to build anticipation and can locate partners and suppliers that have ex- citing new products that appeal to all age groups. If Barna and Beauchamp had instead identified Birchbox’s target market as females ages 16–31, and left the “try new things and learn through discovery” part out, a different set of core com- petencies may have been needed for Birchbox’s overall business model to work. The same philosophy applies across the business model template. The target market a firm selects affects everything it does, from the key assets it acquires to the financing or funding it will need to the partnerships it forms.

Product/Market Scope The fourth element of core strategy is product/ market scope. A company’s product/market scope defines the products and markets on which it will concentrate. Most firms start narrow and pursue adja- cent product and market opportunities as the company grows and becomes finan- cially secure. As explained earlier, new firms typically do not have the resources to produce multiple products and pursue multiple markets simultaneously.

An example is Dropbox, the online data storage company profiled in Case 2.1. When Dropbox was pitching its business idea, a challenge it had was that it was solving a problem that most people didn’t know they had. There were ways for people to transfer files from one device to another, such as USB memory sticks, e-mailing files to yourself, and so forth. Dropbox’s solution was much more elegant. Its service allows users to create a special folder on each of their devices, and sync and store data across devices. Dropbox completely solved the problem of working on a file on one device, such as an office com- puter, and then not having it available on another device, such as a laptop at home. When Dropbox launched in 2008, it had a single product—its online data storage service. The initial market it pursued was tech-savvy people in the Silicon Valley. Since then, Dropbox’s market has expanded to all computer and Internet users; the firm now has 200 million customers. But for the first five years of its existence, it stuck to its initial product, preferring to continually im- prove the quality of its online data storage service rather than developing new services. It wasn’t until 2013 that Dropbox added a second product through the acquisition of Mailbox, an e-mail processing service for mobile devices. Recently, the firm announced a third product, Carousel, which will be a digital gallery that will allow users to share their entire life’s memories. So in terms of product/market scope, Dropbox has progressed as follows:

■ Launch—Single product/Silicon Valley tech-savvy users

■ 1-2 years into existence—Single product/Growing number of Silicon Valley tech-savvy users and people they told about the service

■ 3-4 years into existence—Single product/All computer and Internet users

■ 5 years into existence—Two products/All computer and Internet users

■ 6 years into existence—Three products/All computer and Internet users

This example illustrates a well-thought-out and executed expansion of product/market scope.

In completing the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template, a company should be very clear about its initial product/market scope and project 3-5 years in the future in terms of anticipated expansion. A bullet-point format, as shown for Dropbox above, is acceptable. Similar to all aspects of a company’s business model, its product/market scope will affect other elements of the model.

2. Resources

The second component of a business model is resources. Resources are the inputs a firm uses to produce, sell, distribute, and service a product or ser- vice.20 At a basic level, a firm must have a sufficient amount of resources to enable its business model to work.21 For example, a firm may need a patent (i.e., a key asset) to protect its basis of differentiation. Similarly, a business may need expertise in certain areas (i.e., core competencies) to understand the needs of its target market. At a deeper level a firm’s most important resources, both tangible and intangible, must be both difficult to imitate and hard to find a substitute for in order for the company’s business model to be competitive over the long term. A tangible resource that fits this criterion is Her Campus’s network of 4,000-plus volunteers. As mentioned earlier, it would take a tre- mendous effort for a competitor to amass a similar number of volunteers. In addition, there is no practical substitute for the work that 4,000-plus volun- teers can do. An example of an intangible resource that fits the criterion is Zappos’s reputation for customer service. Zappos is consistently viewed very favorably for its ability to deliver a high level of customer service that is both difficult to imitate and hard to find a substitute for.

Resources are developed and accumulated over a period of time.22 As a result, when completing the Barringer/Ireland Business Plan Template, the current resources a company possesses should be the resources that are noted, but aspirational resources should be kept in mind. For example, it took time for Her Campus to recruit 4,000-plus volunteers. The company may have had 100 volunteers if and when it completed its first business model template. As a result, the proper notation under the Key Assets por – tion of the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template would have been “100 volunteers” (with the goal of adding 100 volunteers a month) or whatever the exact number might have been.

Core Competencies A core competency is a specific factor or capabil- ity that supports a firm’s business model and sets it apart from its rivals.23 A core competency can take on various forms, such as technical know-how, an efficient process, a trusting relationship with customers, expertise in product design, and so forth. It may also include factors such as passion for a business idea and a high level of employee morale. A firm’s core competencies largely determine what it can do. For example, many firms that sell physical prod- ucts do not do their own manufacturing because manufacturing is not a core competency. Instead, their core competencies may be in areas such as product design and marketing. The key idea is that to be competitive a business must be particularly good at certain things, and those certain things must be sup- portive of all elements of its business model. For example, Netflix is particu- larly good at supply chain management, which was essential during the years that Netflix’s business model was geared primarily towards delivering DVDs to customers via the mail. Without a core competency in supply chain manage- ment, Netflix’s entire business model would not have worked.

Most start-ups will list two to three core competencies on the business model template. Consistent with the information provided above, a core compe- tency is compelling if it not only supports a firm’s initiatives, but is also difficult to imitate and substitute. Few start-ups have core competencies in more than two to three areas. For example, Her Campus has three core competencies:

■ Creating content of interest to active college-aged females

■ Recruiting and managing a volunteer network

■ Connecting active college-aged females with major brands

Similar to the Netflix and supply chain management example, Her Campus’s entire business model would be untenable absent these three core competen- cies. In Her Campus’s case, an added advantage is that its core competencies are, at varying levels, difficult to imitate and hard to find substitutes for.

Key assets Key assets are the assets that a firm owns that enable its business model to work.24 The assets can be physical, financial, intellectual, or human. Physical assets include physical space, equipment, vehicles, and distribution networks. Intellectual assets include resources such as patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets, along with a company’s brand and its reputation. Financial assets include cash, lines of credit, and commitments from investors. Human assets include a company’s founder or founders, its key employees, and its advisors.

Firms vary regarding the key assets they prioritize and accumulate. All companies require financial assets to varying degrees. Retailers such as Whole Foods Markets and Amazon rely heavily on physical assets—Whole Foods because of its stores and Amazon because of its warehouses and distribu- tion network. Companies such as Uber rely almost exclusively on intellectual assets. Uber does not employ the drivers that provide its customers rides or own the cars they ride in. It simply provides a technology-based platform that connects people wanting rides with people willing to provide them. As a result, Uber’s key assets are an app, its brand, and the relationships it has with its customers, drivers, and the communities in which it operates. Many compa- nies rely heavily on human assets. The success of Zynga’s business model, for example, relies heavily on its ability to attract and retain a group of game producers and programmers who are creative enough and proficient enough to continually come up with online games that are engaging and social.

Obviously, different key resources are needed depending on the business model that a firm conceives. In filling out the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template, a firm should list the three to four key assets that it pos- sesses that support its business model as a whole. In some cases, the ongoing success of a firm’s business model hinges largely on a single key resource. For example, Zynga has historically maintained an agreement with Facebook that provided Zynga a privileged position on Facebook’s platform. In 2013, that agreement came to end, which weakened Zynga’s business model and dimmed its future prospects.

3. Financials

The third component of a business model focuses on its financials. This is the only section of a firm’s business model that describes how it earns money— thus, it is extremely important. For most businesses, the manner in which it makes money is one of the most fundamental aspects around which its busi- ness model is built.25 The primary aspects of financials are: revenue streams, cost structure, and financing/funding.

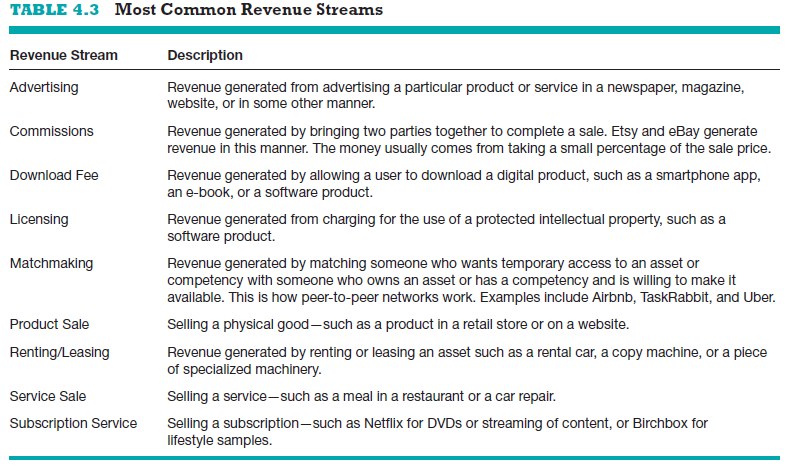

Revenue Streams A firm’s revenue streams describe the ways in which it makes money.26 Some businesses have a single revenue stream, while oth- ers have several. For example, most restaurants have a single revenue stream. Their customers order a meal and pay for it when they’re finished eating. Other restaurants have several revenue streams. They may operate a restaurant, offer a catering service, and sell products at their counter, such as bottled barbeque sauce in the case of a barbeque restaurant. The nature of the way businesses make money also varies. Some businesses make money via one- time customer payments, while others receive recurring revenue by selling a subscription service. Some businesses are very creative in the ways in which they make money. For example, many providers of online games offer the basic game for free, and generate most of their revenue from a small number of us- ers who purchase premium products such as time-saving shortcuts, special weapons, and other features to enhance play.

The most common revenue streams are shown in Table 4.3. As noted above, many businesses have more than one revenue stream, primarily to le- verage the value they are creating for their customers. For example, Birchbox has two revenue streams—its subscription service and its online store. For $10 a month, its subscribers receive four to five product samples. If a cus- tomer wants to buy a full-sized version of one of the samples, it is available via Birchbox’s online store. For Birchbox, having two revenue streams makes per- fect sense. The product samples introduce subscribers to products that they might not have known about otherwise. If a subscriber likes a particular prod- uct and wants a full-sized version, it is available via Birchbox’s website. The arrangement is good for the subscriber and is good for Birchbox. It provides the subscriber a convenient way to buy a product that he or she just sampled, and provides Birchbox dual revenue streams.

The number and nature of a business’s revenue streams has a direct im- pact on the other elements of its business model. All for-profit businesses need at least one revenue stream to fund their operations. Whether additional rev- enue streams add or subtract value depends on the nature of the business and the other elements of its business model. It makes sense for Birchbox to have two revenue streams, as explained above. It also makes sense for a retail store, such as a bicycle shop, to not only sell bicycles (Revenue Stream #1), but to sell bicycle accessories (Revenue Stream #2), offer bicycle repair services (Revenue Stream #3), and sponsor local bicycle races (Revenue Stream #4). In contrast, the seller of a smartphone app may charge a one-time download fee (Revenue Stream #1) and offer product upgrades (Revenue Stream #2). But the seller may stop short of selling online advertising (Potential Revenue Stream #3), fearing that online advertising would detract from the experience of playing the game and lead to poorer user reviews and ultimately fewer downloads.

In filling out the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template, you should clearly identify your revenue streams. Placing them in bullet-point format is preferable.

Cost Structure A business’s cost structure describes the most important costs incurred to support its business model.27 It costs money to establish a basis of differentiation, develop core competencies, acquire or develop key as- sets, form partnerships, and so on. Generally, the goal for this box in a firm’s business model template is threefold: identify whether the business is a cost- driven or value-driven business, identify the nature of the business’s costs, and identify the business’s major cost categories.

Initially, it is important to determine the role of costs in a business. Businesses can be categorized as cost-driven or value-driven. Cost-driven busi- nesses focus on minimizing costs wherever possible. An example is Warby Parker, the subject of Case 5.2. Warby Parker sells prescription glasses for

$95, which is well below the price charged by stores like Pearle Vision and LensCrafters. To do this, Warby Parker’s entire business model is based on cost containment. Its glasses are designed in-house, manufactured overseas, and sold via the Web, eliminating many of the costs associated with traditional glasses manufacturing and retailing. Instead of concentrating on driving costs lower and lower relative to rivals’ cost structures, value-driven business models focus on offering a high-quality product (or experience) and personalized service. Optometrists routinely sell prescription glasses in the $400 to $500 price range.

The additional value they provide is a wide selection, personalized service select- ing and fitting the glasses, and free follow-on services if the glasses need to be adjusted or repaired.

Next, it’s important to identify the nature of a business’s costs. Most businesses have a mainly fixed-cost or variable-cost structure. Fixed costs are costs that remain the same despite the volume of goods or services provided. Variable costs vary proportionally with the volume of goods or services produced. The reason that it’s important to know this is that it impacts the other elements of a firm’s business model. Developing smart- phone apps, for example, involves large fixed costs (i.e., the coding and development of the app) and small variable costs (i.e., the incremental costs associated with each additional app that is sold). As a result, a large amount of money will be needed up front, to fund the initial development, but not so much downstream, to fund the ongoing sales of the app. In contrast, a business such as a sub sandwich shop may have low fixed costs and high variable costs. The initial cost to set up the business may be modest, particularly if it is located in a leased facility, but the cost of labor and ingredients needed to prepare and serve the sandwiches may be high rela- tive to the prices charged. This type of business may need a smaller up-front investment but may require a line of credit to fund its ongoing operations. Other elements of the business model may also be affected. For example, a business with substantial fixed costs, such as an airline, has typically made a major investment in key assets. A service-based company may have few key assets but may have core competencies and a partnership network that allows it to source raw materials, prepare products, and reliably deliver the finished products to its customers.

The third element of cost structure is to identify the business’s major cost categories. At the business model stage, it is not necessary to establish a bud- get or prepare pro-forma financial projections. It is necessary, however, to have a sense of a firm’s major categories of costs. For example, Facebook’s major categories of costs are data center costs, marketing and sales, research and development, and general and administrative. This type of breakdown helps a business understand where its major costs will be incurred. It will also provide anyone looking at the business model template a sense of the major cost items that a company’s business model relies on.

Financing/Funding Finally, many business models rely on a certain amount of financing or funding to bring their business model to life. For example, Birchbox’s business model may have looked elegant on paper, but the firm needed an infusion of investment dollars to get up and running. Most businesses incur costs prior to the time they generate revenue. Think of a business such as SuperJam, the subject of the opening feature in Chapter 1. Prior to earning revenue the company had to design its product, arrange for manufacturing, purchase inventory, acquire customers, and ship its product to its customers. This sequence, which is common, typically necessitates an infusion of up-front capital for the business to be feasible. Absent the capital, the entire business model is untenable.

Some entrepreneurs are able to draw from personal resources to fund their business. In other cases, the business may be simple enough that it is funded from its own profits from day one. In many cases, however, an initial infusion of funding or financing is required, as described above. In these cases, the business model template should indicate the approximate amount of funding that will be needed and where the money is most likely to come from.

Similar to cost structure, at the business model stage projections do not need to be completed to determine the exact amount of money that is needed. An approximation is sufficient. There are three categories of costs to consider: capital costs, one-time expenses, and provisions for ramp-up expenses. In regard to capital costs, this category includes real estate, buildings, equip- ment, vehicles, furniture, fixtures, and similar capital purchases. These costs vary considerably depending on the business. A restaurant or retail store may have substantial capital costs, while a service business may have little or no capital costs. The second category includes one-time expenses such as legal expenses to launch the business, website design, procurement of initial inventory, and similar one-time expenses and fees. All businesses incur at least some of these expenses. Finally, a business must allow for ramp-up ex- penses. Many businesses require a ramp-up period in which they lose money until they are fully up to speed and reach profitability. For example, it usually takes a new fitness center several months to reach its membership goals and achieve profitability. It’s important to have cash set aside to make it through this period.

4. Operations

The final quadrant in a firm’s business model focuses on operations. Operations are both integral to a firm’s overall business model and represent the day-to- day heartbeat of a firm. The primary elements of operations are: product (or service) production, channels, and key partners.

Product (or Service) Production This section focuses on how a firm’s products and/or service are produced. If a firm sells physical products, the products can be manufactured or produced in-house, by a contract manu- facturer, or via an outsource provider. This decision has a major impact on all aspects of a firm’s business model. If it opts to produce in-house, it will need to develop core competencies in manufacturing and procure key assets related to the production process. It will also require substantial up-front investment. If a firm that produces a physical product opts to use a contract manufacturer or an outsource provider, then a critical aspect of its business model is its ability to locate a suitable contract manufacturer or outsource provider. This is not a trivial activity. It’s often difficult to find a contract manufacturer or outsource provider that will take a chance on a start-up. As a result, in the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template, it is not suffi- cient to complete this box by simply saying “Manufacturing will be completed by a contract manufacturer.” The exact name of the manufacturer is not necessary, but a general sense of what part of the world the manufacturer is located in and the type of arrangement that will be forged with the manufac- turer is needed.

If a firm is providing a service rather than a physical product, a brief description of how the service will be produced should be provided. For ex- ample, Rover.com, the subject of Case 2.2, is a service that matches people who need their dogs watched while they are out of town with individuals who are willing to watch and care for dogs. The business model template needs to briefly report how this works. The explanation does not need to be lengthy, but it needs to be substantive. For example, an acceptable description for Rover.com is as follows:

Rover.com will connect dog owners and dog sitters via a website. The dog sitters will be screened to ensure a quality experience. Customer support will be provided 24/7 to troubleshoot any problems that occur. Pet insurance is provided that covers any medical bills that a dog has while in the care of a Rover.com sitter.

This brief statement provides a great deal of information about how Rover. com works and how the elements of its business model need to be configured. This is information that isn’t provided in another box in the business model template.

Channels A company’s channels describe how it delivers its product or service to its customers.28 Businesses sell direct, through intermediaries, or through a combination of both.

Many businesses sell direct, through a storefront and/or online. For example, Warby Parker sells its eyewear via its website and in a small number of company-owned stores. It does not sell via intermediaries, such as distribu- tors and wholesalers. In contrast, SuperJam sells direct, via its website, and also through supermarkets throughout the country. It utilizes distributors and wholesalers to get its bikes into stores. Some companies sell strictly through intermediaries. For example, some of the manufacturers that sell via Zappos and Amazon do not maintain a storefront or sell via a website of their own. They strictly rely on broadly trafficked sites such as Zappos and Amazon to sell their products.

The same holds true for firms that sell services. Hotels, for example, sell their services (typically rooms) directly through their websites and telephone reservation services, and also through intermediaries such as travel agents, tour operators, airlines, and so forth. For example, if you were planning a trip to San Francisco, you could book your flight, rental car, and hotel through Travelocity, Expedia, or many other similar services. In this instance, Travelocity and the others act as intermediaries for the service providers.

A firm’s selection of channels affects other aspects of its business model. Warby Parker maintains a simple channels strategy, selling strictly through its website and a small number of company-owned stores. Its price point is low enough that it must capture 100 percent of its margins for itself for its business model to work. In contrast, GoPro sells its cameras through its website, via on- line outlets such as Amazon and BestBuy.com, and through hundreds of retail stores in the United States and abroad. It utilizes intermediaries, such as whole- salers and distributors, to help it find new outlets. GoPro has a value-driven cost structure, so it can afford to share some of its margins with channel partners. The advantage of GoPro’s approach is wide dissemination of its products both online and in retail outlets.

Some firms employ a sales force that calls on potential customers to try to close sales. This is an expensive strategy but necessary in some instances. For example, if a firm is selling a new piece of medical equipment that needs to be demonstrated to be sold, fielding a sales force may be the only realistic option.

Key Partners The final element of a firm’s business model is key partners. Start-ups, in particular, typically do not have sufficient resources (or funding) to perform all the tasks needed to make their business models work, so they rely on partners to perform key roles. In most cases, a business does not want to do everything itself because the majority of tasks needed to build a prod- uct or deliver a service are outside a business’s core competencies or areas of expertise.

The first partnerships that many businesses forge are with suppliers. A supplier (or vendor) is a company that provides parts or services to another company. Almost all firms have suppliers who play vital roles in the function- ing of their business models. Traditionally, firms maintained an arm’s-length relationship with their suppliers and viewed them almost as adversaries. Producers needing a component part would negotiate with several suppliers to find the best price. Today, firms are moving away from this approach and are developing more cooperative relationships with suppliers. More and more, managers are focusing on supply chain management, which is the coordination of the flow of all information, money, and material that moves through a prod- uct’s supply chain. The more efficiently an organization can manage its supply chain, the more effectively its entire business model will work.

Along with suppliers, firms partner with other companies to make their business models work. The most common types of relationships, which include strategic alliances and joint ventures, are shown in Table 4.4. The advantages of participating in partnerships include: gaining access to a particular resource, risk and cost sharing, speed to market, and learning.29 An example is a partner- ship between Zynga, the online games company, and Hasbro, a long-time maker of board games. In 2012, the two companies formed a partnership, which re- sulted in the production of Zynga-themed adaptations of classic Hasbro games. Hasbro now makes a board game called FarmVille Hungry Hungry Herd, which is an adaptation of Zynga’s popular FarmVille online game. The partnership is good for both Zynga and Hasbro. It provides Zynga a new source of revenue and entry into a new industry, board games, and it provides Hasbro a fresh new game to sell to its customers.30 Partnerships also have potential disadvan- tages.31 The disadvantages include loss of proprietary information, management complexities, and partial loss of decision autonomy.32

When completing the Barringer/Ireland Business Model Template, you should identify your primary supplier partnerships and other partnerships. Normally, a start-up begins with a fairly small number of partnerships, which grows over time.

One trend in partnering, utilized by all types of businesses, is to use free- lancers to do jobs that are outside their core competencies. A freelancer is an independent contractor that has skills in a certain area, such as software de- velopment or website design. There are several Web platforms that are making it increasingly easy to identify and find qualified freelancers. These platforms are highlighted in the Partnering for Success boxed feature.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about website. Regards

Thank you for your article.Much thanks again. Will read on…

I like the valuable info you provide in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and take a look at again right here frequently. I am somewhat certain I will be informed many new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good. I do not know who you are but definitely you’re going to a famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

I enjoy what you guys tend to be up too. This kind of clever work and coverage! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve included you guys to blogroll.

Your an expert writer. I must save and revisit your website.

I love the details on your websites. Thank you!|

I love looking through an article that will make people think. Also, many thanks for allowing me to comment!

There is definately a lot to learn about this issue. I like all of the points you made.

After study a few of the blog posts on your website now, and I truly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Pls check out my web site as well and let me know what you think.

You’ve been terrific to me. Thank you!

Thanks for posting such an excellent article. It helped me a lot and I love the subject matter.

I’ve to say you’ve been really helpful to me. Thank you!

I really appreciate your help