We’re ready to describe the general stages in the business buying-decision process. Patrick J. Robinson and his associates identified eight stages and called them buyphases.31 The model in Table 7.1 is the buygrid framework.

In modified-rebuy or straight-rebuy situations, some stages are compressed or bypassed. For example, the buyer normally has a favorite supplier or a ranked list of suppliers and can skip the search and proposal solicitation stages. Here are some important considerations in each of the eight stages.

1. PROBLEM RECOGNITION

The buying process begins when someone in the company recognizes a problem or need that can be met by acquiring a good or service. The recognition can be triggered by internal or external stimuli. The internal stimulus might be a decision to develop a new product that requires new equipment and materials or a machine that breaks down and requires new parts. Or purchased material turns out to be unsatisfactory and the company searches for another supplier or lower prices or better quality. Externally, the buyer may get new ideas at a trade show, see an ad, receive an e-mail, read a blog, or receive a call from a sales representative who offers a better product or a lower price. Business marketers can stimulate problem recognition by direct marketing in many different ways.

2. GENERAL NEED DESCRIPTION AND PRODUCT SPECIFICATION

Next, the buyer determines the needed item’s general characteristics and required quantity. For standard items, this is simple. For complex items, the buyer will work with others—engineers, users—to define characteristics such as reliability, durability, or price. Business marketers can help by describing how their products meet or even exceed the buyers needs.

The buying organization now develops the item’s technical specifications. Often, the company will assign a product-value-analysis engineering team to the project. Product value analysis (PVA) is an approach to cost reduction that studies whether components can be redesigned or standardized or made by cheaper methods of production without adversely affecting product performance. The PVA team will identify overdesigned components, for instance, that last longer than the product itself. Tightly written specifications allow the buyer to refuse components that are too expensive or that fail to meet specified standards.

Suppliers can use product value analysis as a tool for positioning themselves to win an account. Whatever the method, it is important to eliminate excessive costs. Mexican cement giant Cemex is famed for “The Cemex Way” which uses high-tech methods to squeeze out inefficiencies.32

3. SUPPLIER SEARCH

The buyer next tries to identify the most appropriate suppliers through trade directories, contacts with other companies, trade advertisements, trade shows, and the Internet. The move to online purchasing has far-reaching implications for suppliers and will change the shape of purchasing for years to come. Companies that purchase online are utilizing electronic marketplaces in several forms:

- Catalog sites. Companies can order thousands of items through electronic catalogs, such as W. W. Grainger’s, distributed by e-procurement software.

- Vertical markets. Companies buying industrial products such as plastics, steel, or chemicals or services such as logistics or media can go to specialized Web sites called e-hubs. Plastics.com allows plastics buyers to search the best prices among thousands of plastics sellers.

- “Pure Play” auction company. Ritchie Bros. Auctioneers is the world’s largest industrial auctioneer, with 44 auction sites worldwide. It sold $3.8 billion of used and unused equipment at more than 356 unreserved auctions in 2013, including a wide range of heavy equipment, trucks, and other assets for the construction, transportation, agricultural, material handling, oil and gas, mining, forestry, and marine industry sectors. While some people prefer to bid in person at Ritchie Bros. auctions, they can also do so online in real time at rbauction.com—the company’s multilingual Web site. In 2013, 50 percent of the bidders at Ritchie Bros. auctions bid over the Internet; online bidders purchased $1.4 billion of equipment.33

- Spot (or exchange) markets. On spot electronic markets, prices change by the minute. IntercontinentalExchange (ICE) is the leading electronic energy marketplace and soft commodity exchange with billions in sales.

- Private exchanges. Hewlett-Packard, IBM, and Walmart operate private exchanges to link with specially invited groups of suppliers and partners over the Web.

- Barter markets. In barter markets, participants offer to trade goods or services.

- Buying alliances. Several companies buying the same goods can join together to form purchasing consortia to gain deeper discounts on volume purchases. TopSource is an alliance of firms in the retail and wholesale food-related businesses.

Online business buying offers several advantages: It shaves transaction costs for both buyers and suppliers, reduces time between order and delivery, consolidates purchasing systems, and forges more direct relationships between partners and buyers. On the downside, it may help to erode supplier-buyer loyalty and create potential security problems.

E-PROCUREMENT Web sites are organized around two types of e-hubs: vertical hubs centered on industries (plastics, steel, chemicals, paper) and functional hubs (logistics, media buying, advertising, energy management). In addition to using these Web sites, companies can use e-procurement in other ways:

- Set up direct extranet links to major suppliers. A company can set up a direct e-procurement account at Dell or Office Depot, for instance, and its employees can make their purchases this way.

- Form buying alliances. A number of major retailers and manufacturers such as Acosta, Ahold, Best Buy, Carrefour, Family Dollar Stores, Lowe’s, Safeway, Sears, SUPERVALU, Target, Walgreens, Walmart, and Wegmans Food Markets are part of a data-sharing alliance called 1SYNC. Several auto companies (GM, Ford, Chrysler) formed Covisint for the same reason. Covisint is the leading provider of services that can integrate crucial business information and processes between partners, customers, and suppliers. The company has now also targeted health care to provide similar services.

- Set up company buying sites. General Electric formed the Trading Process Network (TPN), where it posts requests for proposals (RFPs), negotiates terms, and places orders.

Moving into e-procurement means more than acquiring software; it requires changing purchasing strategy and structure. However, the benefits are many. Aggregating purchasing across multiple departments yields larger, centrally negotiated volume discounts, a smaller purchasing staff, and less buying of substandard goods from outside the approved list of suppliers.

LEAD GENERATION The supplier’s task is to ensure it is considered when customers are—or could be—in the market and searching for a supplier. Marketing must work with sales to define what makes a “sales ready” prospect and cooperate to send the right messages via sales calls, trade shows, online activities, PR, events, direct mail, and referrals.

Marketers must find the right balance between the quantity and quality of leads. Too many leads, even of high quality, and the sales force may be overwhelmed and allow promising opportunities to fall through the cracks; too few or low-quality leads and the sales force may become frustrated or demoralized.34

To generate high-quality leads, suppliers need to know about their customers. They can obtain background information from vendors such as Dun & Bradstreet and InfoUSA or information-sharing Web sites such as Jigsaw and LinkedIn.35

Suppliers that qualify may be visited by the buyer’s agents, who will examine the suppliers’ manufacturing facilities and meet their staff. After evaluating each company, the buyer will end up with a short list of qualified suppliers. Many professional buyers have forced suppliers to make adjustments to their marketing proposals to increase their likelihood of making the cut.

4. PROPOSAL SOLICITATION

The buyer next invites qualified suppliers to submit written proposals. After evaluating them, the buyer will invite a few suppliers to make formal presentations.

Business marketers must be skilled in researching, writing, and presenting proposals as marketing documents that describe value and benefits in customer terms. Oral presentations must inspire confidence and position the company’s capabilities and resources so they stand out from the competition.

Proposals and selling efforts are often team efforts that leverage the knowledge and expertise of coworkers. Pittsburgh-based Cutler-Hammer, part of Eaton Corp., developed “pods” of salespeople focused on a particular geographic region, industry, or market concentration.

5. SUPPLIER SELECTION

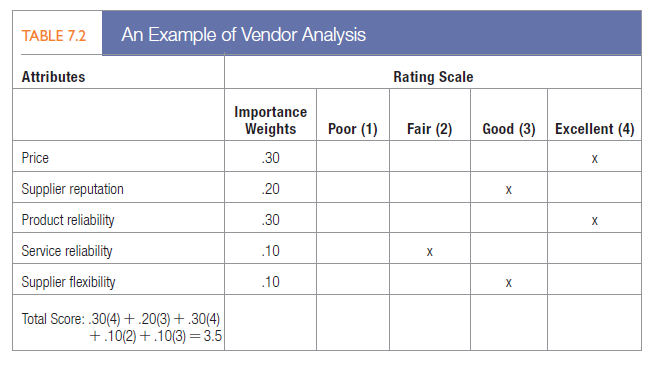

Before selecting a supplier, the buying center will specify and rank desired supplier attributes, often using a supplier-evaluation model such as the one in Table 7.2.

To develop compelling value propositions, business marketers need to better understand how business buyers arrive at their valuations.36 Researchers have identified eight different customer value assessment (CVA) methods. Companies tended to use the simpler methods, though the more sophisticated ones promise a more accurate picture of CPV (see “Marketing Memo: Developing Compelling Customer Value Propositions”).

The choice of attributes and their relative importance vary with the buying situation. Delivery reliability, price, and supplier reputation are important for routine-order products. For procedural-problem products, such as a copying machine, the three most important attributes are technical service, supplier flexibility, and product reliability. For political-problem products that stir rivalries in the organization (such as the choice of a computer system or software platform), the most important attributes are price, supplier reputation, product reliability, service reliability, and supplier flexibility.

OVERCOMING PRiCE PRESSURES Despite moves toward strategic sourcing, partnering, and participation in cross-functional teams, buyers still spend a large chunk of their time haggling with suppliers on price. The number of price-oriented buyers can vary by country, depending on customer preferences for different service configurations and characteristics of the customer’s organization.37

Marketers can counter requests for a lower price in a number of ways, including framing as noted above. They may also be able to show that the total cost of ownership, that is, the life-cycle cost of using their product, is lower than for competitors’ products. They can cite the value of the services the buyer now receives, especially if it is superior to that offered by competitors.38 Research shows that service support and personal interactions, as well as a supplier’s know-how and ability to improve customers’ time to market, can be useful differentiators in achieving key-supplier status.

Improving productivity helps alleviate price pressures. Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway has tied 30 percent of employee bonuses to improvements in the number of railcars shipped per mile.40 Some firms are using technology to devise novel customer solutions. With Web technology and tools, Vistaprint printers can offer professional printing to small businesses that previously could not afford it.41

Some companies handle price-oriented buyers by setting a lower price but establishing restrictive conditions: (1) limited quantities, (2) no refunds, (3) no adjustments, and (4) no services.42

- Cardinal Health set up a bonus-dollars plan and gave points according to how much the customer purchased. The points could be turned in for extra goods or free consulting.

- GE is installing diagnostic sensors in its airline engines and railroad engines. It is now compensated for hours of flight or railroad travel.

- IBM is now more of a “service company aided by products” than a “product company aided by services.” It can sell computer power on demand (like video on demand) as an alternative to selling computers.

Solution selling can also alleviate price pressure and comes in different forms. Here are three examples.43

- Solutions to enhance customer revenues. Hendrix UTD has used its sales consultants to help farmers deliver an incremental animal weight gain of 5 percent to 10 percent over competitors.

- Solutions to decrease customer risks. ICI Explosives formulated a safer way to ship explosives for quarries.

- Solutions to reduce customer costs. W. Grainger employees work at large customer facilities to reduce materials-management costs.

More firms are seeking solutions that increase benefits and reduce costs enough to overcome any low-price concerns. Consider the following example.

LINCOLN ELECTRIC Lincoln Electric has a decades-long tradition of working with its customers to reduce costs through its Guaranteed Cost Reduction (GCR) Program. When a customer insists that a Lincoln distributor lower prices to match competitors, the company and the distributor may guarantee that, during the coming year, they will find cost reductions in the customer’s plant that meet or exceed the price difference between Lincoln’s products and the competition’s. The Holland Binkley Company, a major manufacturer of components for tractor trailers, had been purchasing Lincoln Electric welding wire for years. When Binkley began to shop around for a better price on wire, Lincoln Electric developed a package for reducing costs and working together that called for a $10,000 savings but eventually led to a six-figure savings, a growth in business, and a strong long-term partnership between customer and supplier.

Risk and gain sharing can offset price reductions customers request. Suppose Medline, a hospital supplier, signs an agreement with Highland Park Hospital promising $350,000 in savings over the first 18 months in exchange for getting a tenfold increase in the hospital’s share of supplies. If Medline achieves less than this promised savings, it will make up the difference. If it achieves substantially more, it participates in the extra savings. To make such arrangements work, the supplier must be willing to help the customer build a historical database, reach an agreement for measuring benefits and costs, and devise a dispute resolution mechanism.

NUMBER OF SUPPLIERS Companies are increasingly reducing the number of their suppliers. Ford, Motorola, and Honeywell have cut their number of suppliers 20 percent to 80 percent. These companies want their chosen suppliers to be responsible for a larger component system, achieve continuous quality and performance improvement, and at the same time lower prices each year by a given percentage. They expect their suppliers to work closely with them during product development, and they value their suggestions.

There is even a trend toward single sourcing, though companies that use multiple sources often cite the threat of a labor strike, natural disaster, or any other unforseen event as the biggest deterrent to single sourcing. Companies may also fear single suppliers will become too comfortable in the relationship and lose their competitive edge.

6. MARKETING MEMO Developing Compelling Customer Value Propositions

To command price premiums in competitive B-to-B markets, firms must create compelling customer value propositions. The first step is to research the customer. Here are a number of productive research methods:

- Internal engineering assessment—Have company engineers use laboratory tests to estimate the product’s performance characteristics. Weakness: Ignores the fact that the product will have different economic values in different applications.

- Field value-in-use assessment-interview customers about how costs of using a new product compare with those of using an incumbent. The task is to assess how much each cost element is worth to the buyer.

- Focus-group value assessmen—Ask customers in a focus group what value they would put on potential market offerings.

- Direct survey questions—Ask customers to place a direct dollar value on one or more changes in the market offering.

- Conjoint analysis—Ask customers to rank their preferences for alternative market offerings or concepts. Use statistical analysis to estimate the implicit value placed on each attribute.

- Benchmarks—Show customers a benchmark offering and then a new-market offering. Ask how much more they would pay for the new offering or how much less they would pay if certain features were removed from the benchmark offering.

- Compositional approach—Ask customers to attach a monetary value to each of three alternative levels of a given attribute. Repeat for other attributes, then add the values together for any offer configuration.

- Importance ratings—Ask customers to rate the importance of different attributes and their suppliers’ performance on each.

Having done this research, firms can specify the customer value proposition, following a number of important principles. First, clearly substantiate value claims by concretely specifying the differences between your offerings and those of competitors on the dimensions that matter most to the customer. Rockwell Automation identified the cost savings customers would realize from purchasing its pump instead of a competitor’s by using industry-standard metrics of functionality and performance: kilowatt-hours spent, number of operating hours per year, and dollars per kilowatt-hour. Also, make the financial implications obvious.

Second, document the value delivered by creating written accounts of costs savings or added value that existing customers have actually captured by using your offerings. Chemical producer Akzo Nobel conducted a two-week pilot on a production reactor at a prospective customer’s facility to document the advantages of its high-purity metal organics product.

Finally, make sure the method of creating a customer value proposition is well implemented within the company, and train and reward employees for developing a compelling one. Quaker Chemical conducts training programs for its managers that include a competition to develop the best proposals.

Sources: James C. Anderson and Finn Wynstra, “Purchasing Higher-Value, Higher-Price Offerings in Business Markets,” Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing 17 (2010), pp. 29-61; James C. Anderson, Marc Wouters, and Wouter van Rossum, “Why the Highest Price Isn’t the Best Price,” MIT Sloan Management Review, Winter 2010, pp. 69-76; James C. Anderson, Nirmalya Kumar, and James A. Narus, Value Merchants: Demonstrating and Documenting Superior Value in Business Markets (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2007); James C. Anderson, James A. Narus, and Wouter van Rossum, “Customer Value Propositions in Business Markets,” Harvard Business Review, March 2006, pp. 2-10; James C. Anderson and James A. Narus, “Business Marketing: Understanding What Customers Value,” Harvard Business Review, November 1998, pp. 53-65.

7. ORDER-ROUTINE SPECIFICATION

After selecting suppliers, the buyer negotiates the final order, listing the technical specifications, the quantity needed, the expected time of delivery, return policies, warranties, and so on. Many industrial buyers lease heavy equipment such as machinery and trucks. The lessee gains a number of advantages: the latest products, better service, the conservation of capital, and some tax advantages. The lessor often ends up with a larger net income and the chance to sell to customers that could not afford outright purchase.

For maintenance, repair, and operating items, buyers are moving toward blanket contracts rather than periodic purchase orders. A blanket contract establishes a long-term relationship in which the supplier promises to resupply the buyer as needed, at agreed-upon prices, over a specified period of time. Because the seller holds the stock, blanket contracts are sometimes called stockless purchase plans. They lock suppliers in tighter with the buyer and make it difficult for out-suppliers to break in unless the buyer becomes dissatisfied.

Companies that fear a shortage of key materials are willing to buy and hold large inventories. They will sign long-term contracts with suppliers to ensure a steady flow of materials. DuPont, Ford, and several other major companies regard long-term supply planning as a major responsibility of their purchasing managers. For example, General Motors wants to buy from fewer suppliers, which must be willing to locate close to its plants and produce high-quality components. Business marketers are also setting up extranets with important customers to facilitate and lower the cost of transactions. Customers enter orders that are automatically transmitted to the supplier.

Some companies go further and shift the ordering responsibility to their suppliers, using systems called vendor- managed inventory (VMI). These suppliers are privy to the customer’s inventory levels and take responsibility for continuous replenishment programs. Plexco International AG supplies audio, lighting, and vision systems to the world’s leading automakers. Its VMI program with its 40 suppliers resulted in significant time and cost savings and allowed the company to use former warehouse space for productive manufacturing activities.45

8. PERFORMANCE REVIEW

The buyer periodically reviews the performance of the chosen supplier(s) using one of three methods. The buyer may contact end users and ask for their evaluations, rate the supplier on several criteria using a weighted-score method, or aggregate the cost of poor performance to come up with adjusted costs of purchase, including price. The performance review may lead the buyer to continue, modify, or end a supplier relationship.

Many companies have set up incentive systems to reward purchasing managers for good buying performance, leading them to increase pressure on sellers for the best terms.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

19 May 2021

20 May 2021

19 May 2021

19 May 2021

19 May 2021

20 May 2021