Change does not happen easily, but change can be managed. By observing external trends, patterns, and needs, managers use planned change to help the organization adapt to exter- nal problems and opportunities.63 When organizations are caught flat-footed, failing to anticipate or respond to new needs, management is at fault.

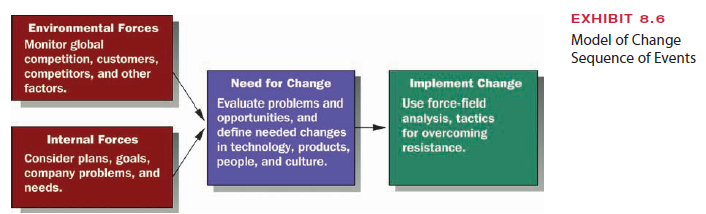

An overall model for planned change is presented in Exhibit 8.6. Three events make up the change sequence: (1) internal and external forces for change exist; (2) organization managers monitor these forces and become aware of a need for change; and (3) the required change is implemented. How each of these activities is handled depends on the organiza- tion and managers’ styles.

We now turn to a brief discussion of the specific activities associated with the first two events—forces for change and the perceived need for the organization to respond. Later, we will discuss change implementation.

1. FORCES FOR CHANGE

Forces for organizational change exist both in the external environment and within the organization.

Environmental Forces. As described in Chapters 3 and 4, external forces origi- nate in all environmental sectors, including customers, competitors, technology, economic forces, and the international arena. For example, shifts in customer tastes led McDonald’s, the giant purveyor of burgers and fries, to begin offering salads, fruit, whole grain muffins, and grilled chicken sandwiches that are perceived as healthier.64 Changes in technology and the health care needs of customers caused Medtronic to shift how it views medical devices, from simply providing therapy to monitoring a patient’s health condition. The company’s cardioverter-defibrillators, for example, can now send information to a secure server, allow- ing medical personnel to review the patient’s condition in real time and identify any prob- lems.65 Increased competition spurred Microsoft to change how it designs and builds soft- ware. With competitors such as Google rapidly introducing innovative software products over the Internet, Microsoft had to find a faster, more flexible way to bring out a new ver- sion of Windows onto which new features can be added one by one over time.66 Technol- ogy has also forced television networks and stations to venture into new territory, as shown in the Spotlight in Technology box.

Internal Forces. Internal forces for change arise from internal activities and deci- sions. If top managers select a goal of rapid company growth, internal actions will have to be changed to meet that growth. New departments or technologies will be created and ad- ditional people hired to pursue growth opportunities. To support growth goals at 3M, CEO James McNerney revved up the company’s product innovation with a new approach to research and development.

Take a moment to complete the New Manager Self Test on openness to change.

By changing the company’s approach to R&D, McNerney and Wendling got 3M’s sales and profits growing again. New business strategies, shifts in the labor pool, demands from unions, and production inefficiencies all can generate a force to which management must respond with change. Production inefficiencies at Chrysler U.S. factories, for example, prompted managers to initiate a total overhaul of the assembly process, resulting in a new, flexible assembly system that makes extensive use of robots and allows for building more than one type of vehicle on a single assembly line. The flexibility can keep Chrysler’s plants run- ning at full capacity, enabling the company to increase profits.68

2. NEED FOR CHANGE

As indicated in Exhibit 8.6, external or internal forces translate into a perceived need for change within the organization. Many people are not willing to change unless they perceive a problem or a crisis. Managers at Humana Inc., for example, changed how the company sells health insurance after losing more than 100,000 private health insurance members in 2005 due to a rapid decrease in the number of small and midsized companies providing benefits to their employees.69 In many cases, however, it is not a crisis that prompts change. Most problems are subtle, so managers have to recognize and then make others aware of the need for change.70

One way managers sense a need for change is through the appearance of a perfor-mance gap—a disparity between existing and desired performance levels. They then try to create a sense of urgency so that others in the organization will recognize and understand the need for change. For example, the chief component-purchasing manager at Nokia no- ticed that order numbers for some of the computer chips it purchased from Philips Elec- tronics weren’t adding up, and he discovered that a fire at Philips’ Albuquerque, New Mexico, plant had delayed production. The manager moved quickly to alert top managers, engineers, and others throughout the company that Nokia could be caught short of chips unless it took action. Within weeks, a crisis team had redesigned chips, found new suppli- ers, and restored the chip supply line. In contrast, managers at a competing firm that also purchased chips from Philips, had the same information but failed to recognize or create a sense of crisis for change, which left the company millions of chips short of what it needed to produce a key product.71

Recall from Chapter 5 the discussion of SWOT analysis. Managers are responsible for monitoring threats and opportunities in the external environment as well as strengths and weaknesses within the organization to determine whether a need for change exists. Managers in every company must be alert to problems and opportunities because the perceived need for change sets the stage for subsequent actions that create a new product or technology. Big problems are easy to spot. Sensitive monitoring systems are needed to detect gradual changes that can fool managers into thinking their company is doing fine. An organization may be in greater danger when the environment changes slowly because managers may fail to trigger an organizational response. Failing to use planned change to meet small needs can place the organization in hot water, as illustrated in the following passage:

When frogs are placed in a boiling pail of water, they jump out—they don’t want to boil to death. However, when frogs are placed in a cold pail of water, and the pail is placed on a stove with the heat turned very low, over time the frogs will boil to death.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

I really value your piece of work, Great post.