1. Planning Types

Managers use strategic, tactical, and operational goals to direct employees and resources toward achieving specific outcomes that enable the organization to perform efficiently and effectively. They take a number of planning approaches, among the most popular of which are management by objectives, single-use plans, standing plans, and contingency plans.

1.1. MANAGEMENT BY OBJECTIVES

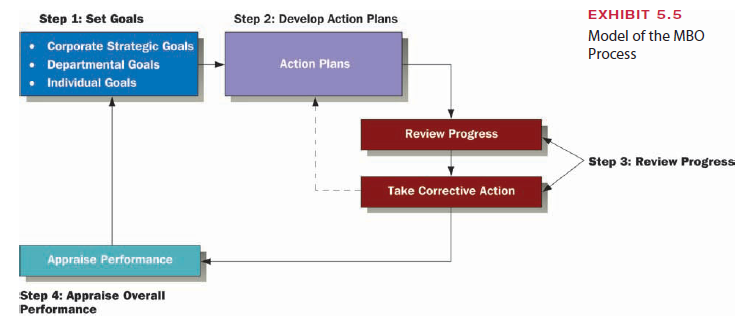

Management by objectives (MBO) is a method whereby managers and employees define goals for every department, project, and person and use them to monitor subsequent performance.26 A model of the essential steps of the MBO process is presented in Exhibit 5.5. Four major activities must occur for MBO to be successful:27

- Set goals. This step is the most difficult in MBO. Setting goals involves employees at all levels and looks beyond day-to-day activities to answer the question: “What are we trying to accomplish?” A good goal is concrete and realistic, provides a specific target and time frame, and assigns responsibility. Goals may be quantitative or qualitative. Quantitative goals are described in numerical terms, such as: “Salesperson Jones will obtain 16 new accounts in ” Qualitative goals use statements such as, “Marketing will reduce complaints by improving customer service next year.” Goals should be jointly derived. Mutual agreement between employee and supervisor creates the strongest commitment to achieving goals. In the case of teams, all team members may participate in setting goals.

- Develop action plans. An action plan defines the course of action needed to achieve the stated goals. Action plans are made for individuals as well as departments.

- Review progress. A periodic progress review is important to ensure that action plans are working. These reviews can take place informally between managers and subordinates, and the organization may wish to conduct 3-, 6-, or 9-month reviews during the year. This periodic checkup allows managers and employees to see whether they are on target or whether corrective action is needed.

Managers and employees should not be locked into predefined behavior and must be willing to take whatever steps are necessary to produce meaningful results. The point of MBO is to achieve goals. The action plan can be changed whenever goals are not being met.

- Appraise overall performance. The final step in MBO is to carefully evaluate whether the annual goals have been achieved for individuals and departments. Success or failure to achieve goals can become part of the performance appraisal system and the designation of salary increases and other rewards. The appraisal of departmental and overall corporate performance shapes the goals for the next year. The MBO cycle repeats itself annually.

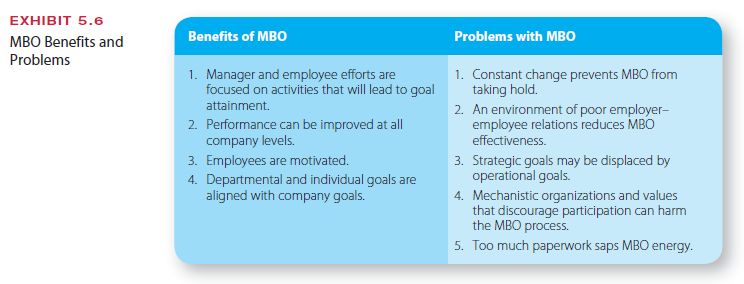

Many companies, including Intel, Tenneco, Black & Decker, and DuPont, have ad- opted MBO, and most managers consider MBO as an effective management tool.28 Man- agers believe they are better oriented toward achieving goals when they are using MBOs. In recent years, the U.S. Congress required that federal agencies adopt a type of MBO sys- tem to encourage government employees to achieve specific outcomes.29 Like any system, MBO achieves benefits when it is used properly but results in problems when it is used im- properly. The benefits and problems of MBOs are summarized in Exhibit 5.6.

Benefits of the MBO process can be many. Corporate goals are more likely to be achieved when they focus on manager and employee efforts. Using a performance measure- ment system such as MBO helps employees see how their jobs and performance contribute to the business, giving them a sense of ownership and commitment.30 Performance is im- proved when employees are committed to attaining the goal, are motivated because they help decide what is expected, and are free to be resourceful. Goals at lower levels are aligned with and enable the attainment of goals at top management levels.

Problems with MBO arise when the company faces rapid change. The environment and internal activities must have some stability for performance to be measured and compared against goals. Setting new goals every few months allows no time for action plans and ap- praisal to take effect. Also, poor employer–employee relations reduce effectiveness because of an element of distrust that may be present between managers and workers. Sometimes goal “displacement” occurs if employees concentrate exclusively on their operational goals to the detriment of other teams or departments. Overemphasis on operational goals can harm the attainment of overall goals.

Another problem arises in mechanistic organizations characterized by rigidly defined tasks and rules that may not be compatible with the emphasis of MBOs on mutual determi- nation of goals by employee and supervisor. In addition, when participation is discouraged, employees will lack the training and values to set goals jointly with employers. Finally, if MBO becomes a process of filling out annual paperwork rather than energizing employees to achieve goals, it becomes an empty exercise. Once the paperwork is completed, employees forget about the goals, perhaps even resenting the paperwork in the first place.

1.2. SINGLE-USE AND STANDING PLANS

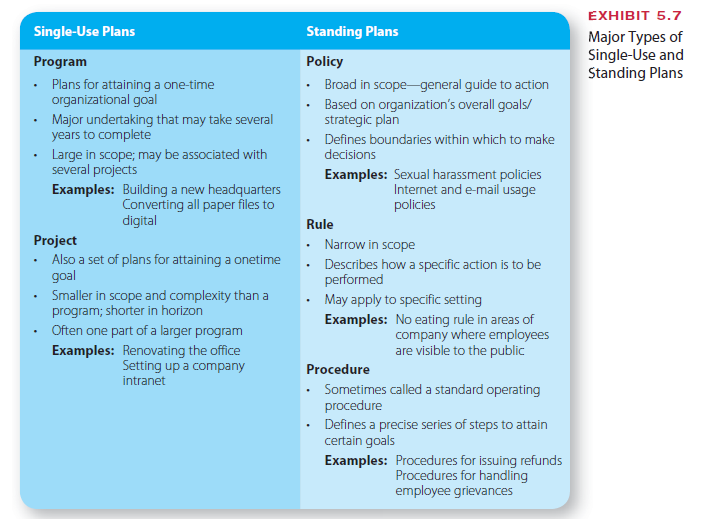

Single-use plans are developed to achieve a set of goals that are not likely to be repeated in the future. Standing plans are ongoing plans that provide guidance for tasks per- formed repeatedly within the organization. Exhibit 5.7 outlines the major types of single- use and standing plans. Single-use plans typically include both programs and projects. The primary standing plans are organizational policies, rules, and procedures. Standing plans generally pertain to matters such as employee illness, absences, smoking, discipline, hiring, and dismissal.

1.3. CONTINGENCY PLANS

When organizations are operating in a highly uncertain environment or dealing with long- time horizons, planning can seem like a waste of time sometimes. In fact, strict plans may even hinder rather than help an organization’s performance in the face of rapid technologi- cal, social, economic, or other environ-mental change. In these cases, managers may want to develop multiple future alternatives to help them form more flexible plans.

Contingency plans define com-pany responses to be taken in the case of emergencies, setbacks, or unexpected conditions.

To develop contingency plans, man- agers identify important factors in the environment, such as possible economic downturns, declining markets, increases in cost of supplies, new technological developments, or safety accidents. Managers then forecast a range of al- ternative responses to the most likely high-impact contingencies, focusing on the worst case.31 For example, if sales fall 20 percent and prices drop 8 percent, what will the company do? Managers could develop contingency plans that include layoffs, emergency budgets, new sales efforts, or new mar- kets. A real-life example comes from FedEx, which has to cope with some kind of unexpected disruption to its service somewhere in the world on a daily basis. In 2005, for example, managers activated contingency plans related to more than two dozen tropical storms, an air traffic controller strike in France, and a blackout in Los Angeles. The company also has contingency plans in place for events such as labor strikes, social upheavals in foreign countries, or incidents of terrorism.32

2. Planning in a Turbulent Environment

Today, contingency planning takes on a whole new urgency as increasing turbulence and uncertainty shake the business world. Managers must renew their emphasis on bracing for unexpected—even unimaginable—events. Two recent extensions of contingency planning are building scenarios and crisis planning.

2.1. BUILDING SCENARIOS

One way managers cope with greater uncertainty is with a forecasting technique known as scenario building. Scenario building involves looking at current trends and dis- continuities and visualizing future possibilities. Rather than looking only at history and thinking about what has been, managers think about what could be. The events that cause the most damage to companies are those that no one even conceived of, such as the collapse of the World Trade Center towers in New York from the terrorist attack.

Although managers can’t predict the future, they can rehearse a framework within which to manage future events.33 With scenario building, a broad base of managers mentally rehearses different scenarios, anticipating various changes that could impact the organization. Scenarios are like stories that offer alternative vivid pictures of what the future will be like and how managers will respond. Typically, two to five scenarios are developed for each set of fac- tors, ranging from the most optimistic to the most pessimistic view.34 Scenario building forces managers to mentally rehearse what they would do if their best-laid plans collapse.

Royal Dutch/Shell has long used scenario building to help managers navigate the tur- bulence and uncertainty of the oil industry. One scenario that Shell managers rehearsed in 1970, for example, involved an imagined accident in Saudi Arabia that severed an oil pipe- line, which in turn decreased supply. The market reacted by increasing oil prices, which allowed OPEC nations to pump less oil and make more money.

This story caused managers to reexamine the standard assumptions about oil price and supply and imagine what would happen and how they would respond if OPEC were to increase prices. Nothing in the exercise told Shell managers to expect an embargo, but by rehearsing this scenario, they were much more prepared than the competition when OPEC announced its first oil embargo in October 1973. This speedy response to a massive shift in the environment enabled Shell to move in two years from being the world’s eighth largest oil company to being number two.35

2.2. CRISIS PLANNING

Some unexpected events are so sudden and devastating that they require imme- diate response. Consider events such as the November 12, 2001, crash of American Airlines Flight 587 in a New York neighborhood that already had been devastated by terrorist attacks, the 1993 deaths from e-coli bacteria in Jack-in-the-Box hamburgers, or the 2003 crash of the Columbia space shuttle. Companies, too, face many smaller crises that call for rapid response, such as the conviction of Martha Stewart, chair of Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, on charges of insider trading; allegations of tainted Coca-Cola in Belgium; or charges that Tyson Foods hired illegal immigrants to work in its processing plants. Crises have become expected in our organizations.36

Although crises differ, a carefully thought-out and coordinated crisis plan can be used to respond to any disaster. In addition, crisis planning reduces the incidence of trouble, much like putting a good lock on a door reduces burglaries.37

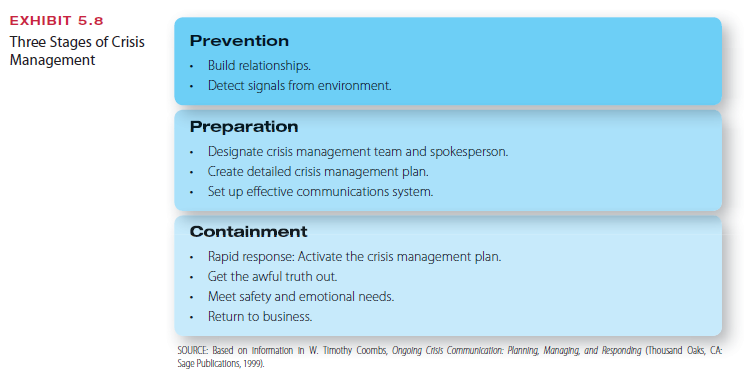

Exhibit 5.8 outlines the three essen- tial stages of crisis management.38 The prevention stage involves activities that managers undertake to try to prevent crises from happening and to detect warning signs of potential crises. The preparation stage includes all the detailed planning to handle a crisis when it arises. Containment focuses on the or- ganization’s response to an actual crisis and any follow-up concerns.

Prevention. Although unexpected events and disasters will happen, managers should do everything they can to prevent crises. Critical to prevention is to build trusting relation- ships with key stakeholders such as employees, customers, suppliers, governments, unions, and the community. By developing favorable relationships, managers often can prevent crises from happening and can respond more effectively to those that cannot be avoided. For example, organizations that have open, trusting relationships with employees and unions may avoid crippling labor strikes.

Good communication also helps managers identify problems early so they do not turn into major issues. Coca-Cola suffered a major crisis in Europe because it failed to respond quickly to reports of “foul-smelling” Coke in Belgium. A former CEO observed that every problem the company has faced in recent years “can be traced to a singular cause: We neglected our relationships.”39

Preparation. The three steps in the preparation stage are

- designating a crisis management team and spokesperson,

- creating a detailed crisis management plan, and

- setting up an effective communications system.

Some companies are setting up crisis management offices, with high-level leaders who report directly to the CEO.40 Although these offices are in charge of crisis management, people throughout the company must be involved. The crisis management team, for exam- ple, is a cross-functional group of people who are designated to swing into action if a crisis erupts. The organization also should designate a spokesperson who will be the voice of the company during the crisis.41 In many cases this person is the top leader. Organizations, however, typically assign more than one spokesperson so someone else will be prepared if the top leader is not available.

The crisis management plan (CMP) is a detailed, written plan that specifies the steps to be taken, and by whom, if a crisis arises. The CMP should include the steps for dealing with various types of crises—natural disasters such as fires or earthquakes, normal accidents such as economic crises or industrial accidents, and abnormal events such as product tampering or acts of terrorism.42

Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, the World Trade Center’s largest tenant with 3,700 em- ployees, adopted a crisis management plan for abnormal events after bomb threats during the Persian Gulf War in 1991. Top managers credit its detailed evacuation procedures for saving the lives of all but six employees during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack.43

A key point is that a crisis management plan should be a living, changing document that is regularly reviewed, practiced, and updated as needed.

Containment. Some crises are inevitable no matter how well prepared an organiza- tion is. When a crisis hits, a rapid response is crucial. Training and practice enable the team to implement the crisis management plan immediately. In addition, the organization should “get the awful truth out” to employees and the public as soon as possible.44 At this stage, the organization must speak with one voice so people do not get conflicting stories about what’s going on and what the organization is doing about it.

After ensuring people’s physical safety, if necessary, during a crisis, the next step should be to respond to the emotional needs of employees, customers, and the public. Presenting facts and statistics to try to downplay the disaster inevitably backfires because it does not meet people’s emotional need to feel that someone cares about them and what the disaster has meant to their lives.

Organizations strive to give people a sense of security and hope by getting back to busi- ness quickly. Companies that cannot get up and running within 10 days after any major cri- sis are not likely to stay in business.45 People want to feel that they are going to have a job and be able to take care of their families. Managers also use a time of crisis to bolster their prevention abilities and be better prepared in the future. Executives at Home Depot do a postmortem after each catastrophic event to learn how to better prepare for the next one.46

A crisis also is an important time for companies to strengthen their stakeholder relation- ships. By being open and honest about the crisis and putting people first, organizations build stronger bonds with employees, customers, and other stakeholders, and they gain a reputation as a trustworthy company.

3. Planning for High Performance

The purpose of planning and goal setting is to help the organization achieve high perfor- mance. Overall organizational performance depends on achieving outcomes identified by the planning process. The process of planning is changing to be more in tune with a rapidly changing environment. Traditionally, strategy and planning have been the domain of top managers. Today, managers involve people throughout the organization, which can spur higher performance because people understand the goals and plans and buy into them.

In a complex and competitive business environment, strategic thinking and execution become the expectation of every employee.47 Planning comes alive when employees are in- volved in setting goals and determining the means to reach them. Here are some guidelines for planning in the new workplace.

- Start with a strong mission and vision. Planning for high performance requires flexi- bility. Employees may have to adapt their plans to meet new needs and respond to changes in the environment. During times of turbulence or uncertainty, a powerful sense of purpose (mission) and direction for the future (vision) become even more im- portant. Without a strong mission and vision to guide employees’ thinking and behav- ior, the resources of a fast-moving company can quickly become uncoordinated, with employees pursuing radically different plans and activities. A compelling mission and vision also can increase employee commitment and motivation, which are vital to help- ing organizations compete in a rapidly shifting environment.48

- Set stretch goals for excellence. Stretch goals are highly ambitious goals that are so clear, compelling, and imaginative that they fire up employees and engender excellence. Stretch goals enable people to think in new ways because they are so far beyond the current levels that people don’t know how to reach them. At the same time, though, as we discussed earlier, the goals must be seen as achievable or employees will be discouraged and demo- 49 Stretch goals are extremely important today because things move fast.

A company that focuses on gradual, incremental improvements in products, pro- cesses, or systems will be left behind. Managers can use stretch goals to compel em- ployees to think in new ways that lead to bold, innovative breakthroughs. Motorola used stretch goals to achieve Six Sigma quality which now has become the standard for numerous companies. Managers first set a goal of a tenfold increase in quality over a two-year period. After this goal was met, the company set a new stretch goal of a hun- dredfold improvement over a four-year period.50

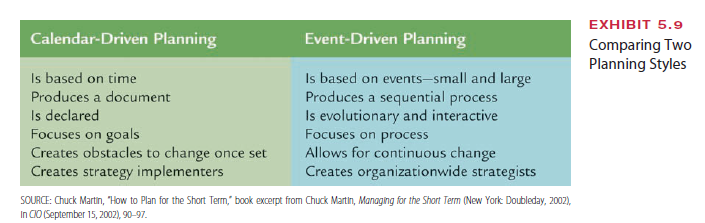

- Embrace event-driven planning. In rapidly shifting environments, managers have to be in tune with what’s happening right now, rather than concentrating only on long-range goals and plans. Long-range strategic planning is not abandoned but is accompanied by event-driven planning, which responds to the current reality of what the environment and the marketplace demand.51 Exhibit 5.9 compares traditional cal- endar-driven planning to event-driven planning.

Event-driven planning is a continuous, sequential process rather than a staid planning document. It is evolutionary and interactive, taking advantage of unforeseen events to shift the company as needed to improve performance. Event-driven planning allows for flexibility to adapt to market forces or other shifts in the environment rather than being tied to a plan that no longer works.

For example, Redix International, a software development firm, has a long-term plan for items it wants to incorporate into the software. But the plan is modified at least four or five times a year. The shifts in direction are based on weekly discussions that president and CEO Randall King has with key Redix managers, where they exam- ine what demands from clients indicate about where the marketplace is going.52

- Use performance dashboards. People need a way to see how plans are progressing and gauge their progress toward achieving goals. Companies began using business performance dashboards as a way for executives to keep track of key performance metrics, such as sales in relation to targets, number of products on back order, or percentage of customer service calls resolved within specified time periods. Today, dashboards are evolving into organization-wide systems that help align and track goals across the enterprise. The true power of dashboards comes from deploying them throughout the company, even on the factory floor, so all employees can track progress toward goals, notice when things are falling short, and find innovative ways to get back on course toward reaching the specified targets.

At Emergency Medical Associates, a physician-owned medical group that manages emergency rooms for hospitals in New York and New Jersey, dashboards enable the staff to note when performance thresholds related to patient wait times, for example, aren’t being met at various hospitals.53 Some dashboard systems also incorporate soft- ware that enables users to perform what-if scenarios to evaluate the impact of various alternatives for meeting goals.

- Organize temporary task forces. A planning task force is a temporary group of man- agers and employees who take responsibility for developing a strategic plan. Many of today’s companies use interdepartmental task forces to help establish goals and make plans for achieving them. The task force often includes outside stakeholders as well, such as customers, suppliers, strategic partners, investors, or even members of the gen- eral community. Today’s companies concentrate on satisfying the needs and interests of all stakeholder groups, so they bring these stakeholders into the planning and goal- setting process.54 LendLease, an Australian real estate and financial services company, for example, involves numerous stakeholders, including community advocates and potential customers, in the planning process for every new project it undertakes.55

- Recognize that planning still starts and stops at the top. Top managers create a mission and vision worthy of employees’ best efforts, which provides a framework for planning and goal setting. Even though planning is decentralized, top managers must show sup-port and commitment to the planning process. Top managers also accept responsibility when planning and goal setting are ineffective, rather than blaming the failure on lower- level managers or employees.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Really fantastic information can be found on web blog.

Your home is valueble for me. Thanks!…