1. Economic Forces

Economic factors have a direct impact on the potential attractiveness of various strategies. For example, high underemployment (minimum wage-type employment) in the United States bodes well for discount firms such as Dollar Tree, T.J. Maxx, Walmart, and Subway, but hurts thousands of traditional-priced retailers in many industries. Although the Dow Jones Industrial Average is high, corporate profits are high, dividend increases are up sharply, gas prices are low, and emerging markets are growing, millions of people work for minimum wages or are unemployed. As a result of droughts, commodity prices are up sharply, especially food, which is contributing to rising inflation fears. Many firms are switching to part-time rather than full-time employees to avoid having to pay health benefits.

To take advantage of Canada’s robust economy and eager-to-spend people, many firms are adding facilities in Canada, including T.J. Maxx opening Marshalls stores and Tanger Outlet Factory Centers stores opening. Canada is one of the most economically prosperous countries in the world. Although interrelated, every country has its own economic situation, and those situations impact where companies choose to spend money and do business.

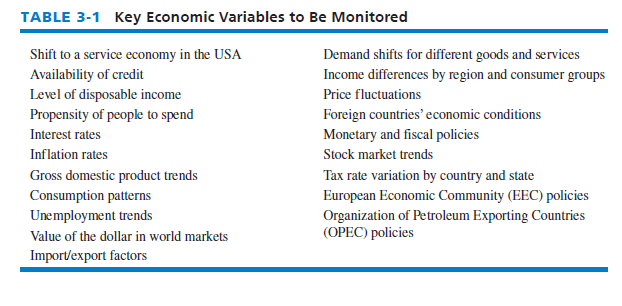

Interest rates, stock prices, and discretionary income are slowly rising. As stock prices increase, the desirability of equity as a source of capital increases. When the market rises, consumer and business wealth expands. A few important economic variables that often represent opportunities and threats for organizations are provided in Table 3-1. Be mindful that in strategic planning and case analysis, relevant economic variables such as those listed must be quantified and actionable to be useful.

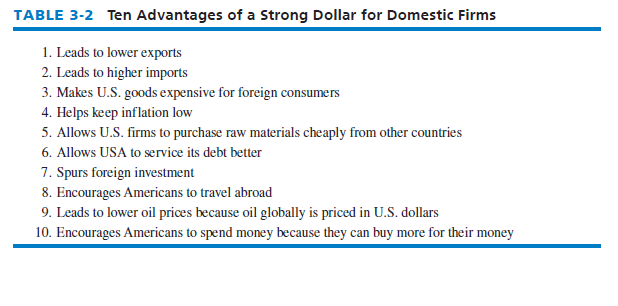

An example of an economic variable is “value of the dollar” that recently hit a 7-year high compared to the yen, a 9-year high compared to the euro, a 5-year high compared to the Australian dollar, and an 11-year high to some other currencies. The high dollar makes it cheap for Americans to travel abroad, but expensive for foreigners to travel to the United States, thus hurting the U.S. tourism business. Trends in the dollar’s value have significant and unequal effects on companies in different industries and in different locations. Agricultural and petroleum industries are hurt by the dollar’s rise against the currencies of Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela, and Australia. Generally, a strong or high dollar makes U.S. goods more expensive in overseas markets. This worsens the U.S. trade deficit.

Domestic firms with big overseas sales, such as McDonald’s, also are hurt by a strong dollar. Its revenue from abroad is lowered because, for example, 100 euros earned in Europe, when translated back to U.S. dollars for reporting purposes, is worth maybe $75. To combat this “loss,” some companies try to raise prices in their European or Mexican stores, but that carries a risk of alienating shoppers, angering retailers, and giving local competitors a price edge. Some advantages of a strong dollar, however, are that (1) companies with substantial outside U.S. operations see their overseas expenses, such as salaries paid in euros, become cheaper; (2) it gives U.S. companies greater firepower for international acquisitions; and (3) companies importing goods have greater buying power because their dollars now go further overseas. Table 3-2 lists 10 advantages of a strong U.S. dollar for U.S. firms.

2. Social, Cultural, Demographic, and Natural Environment Forces

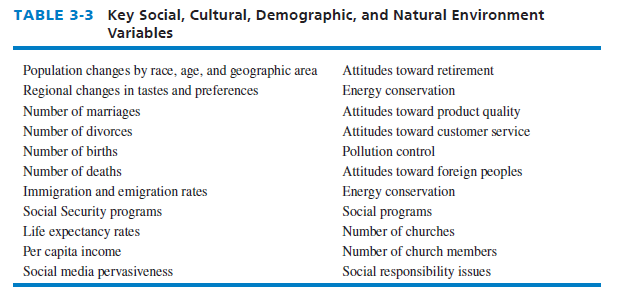

Social, cultural, demographic, and environmental changes impact strategic decisions on virtually all products, services, markets, and customers. Small, large, for-profit, and nonprofit organizations in all industries are being staggered and challenged by the opportunities and threats arising from changes in social, cultural, demographic, and environmental variables. In every way, the United States is much different today than it was yesterday, and tomorrow promises even greater changes.

The United States is becoming older and less white. The oldest among the 76 million baby boomers plan to retire soon, and this has lawmakers and younger taxpayers concerned about who will pay their Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Individuals age 65 and older in the United States as a percentage of the population will rise to 18.5 percent by 2025. The oldest American as of January 1, 2015, is 116-year-old Gertrude Weaver of Little Rock, Arkansas. Weaver is the second-oldest person in the world, behind Misao Okawa of Japan, according to the Gerontology Research Group.

The trend toward an older United States is good news for restaurants, hotels, airlines, cruise lines, tours, resorts, theme parks, luxury products and services, recreational vehicles, home builders, furniture producers, computer manufacturers, travel services, pharmaceutical firms, automakers, and funeral homes. Older Americans are especially interested in health care, financial services, travel, crime prevention, and leisure. The world’s longest-living people are the Japanese. By 2050, the Census Bureau projects that the number of Americans age 100 and older will increase to over 834,000 from just under 100,000 centenarians in the country in 2000. Americans age 65 and over will increase from 12.6 percent of the U.S. population in 2000 to 20.0 percent by the year 2050. The aging U.S. population affects the strategic orientation of nearly all organizations.

Retail shoppers in the United States are increasingly buying online, resulting in a persistent 5 to 7 percent decline in store traffic among almost all retail stores, prompting chains to slow or cease store openings.1 Research reveals that growth in store counts at the 100 largest retailers by revenue slowed to 2 percent in 2014 from more than 12 percent in 2011. Consumer tastes and trends are changing as people wander through stores less, opting more and more to use their mobile phones and computers to research prices and cherry-pick promotions. Sales derived from online purchases are rapidly increasing.

The historical trend of people moving from the Northeast and Midwest to the Sunbelt and West has slowed, but there remains a steady migration to coastal areas. Hard-number data related to this trend can represent key opportunities for many firms and thus can be essential for successful strategy formulation, including where to locate new plants and distribution centers and where to focus marketing efforts.

Fortune recently ranked the largest 100 U.S. cities according to the best managed and worst managed.2 A variety of factors were included, such as the area’s economy, job market, crime level, and welfare of the population. The best-managed city is Irvine, California, followed by Fremont, California; Plano, Texas; Lincoln, Nebraska; Virginia Beach, Virginia; Scottsdale, Arizona; Seattle, Washington; Austin, Texas; Chesapeake, Virginia, and Raleigh, North Carolina.

By 2075, the United States will have no racial or ethnic majority. This forecast is aggravating tensions over issues such as immigration and affirmative action. Hawaii, California, and New Mexico already have no majority race or ethnic group. The population of the world recently surpassed 7 billion; the United States has slightly more than 310 million people. That leaves literally billions of people outside the United States who may be interested in the products and services produced through domestic firms. Remaining solely domestic is an increasingly risky strategy, especially as the world population continues to grow to an estimated 8 billion in 2028 and 9 billion in 2054.

Social, cultural, demographic, and environmental trends are shaping the way Americans live, work, produce, and consume. New trends are creating a different type of consumer and, consequently, a need for different products, new services, and updated strategies. One trend is that there are now more U.S. households with people living alone or with unrelated people than there are households consisting of married couples with children. Another is that U.S. households are making more and more purchases online.

Some important social, cultural, demographic, and environmental variables that represent opportunities or threats for virtually all organizations is given in Table 3-3. Be mindful that in strategic planning and case analysis, relevant social, cultural, demographic, and natural environment factors for a particular business must be quantified and actionable to be useful.

3. Political, Governmental, and Legal Forces

Political issues and stances do matter for business and do impact strategic decisions, especially in today’s world of instant tweeting and emailing. Various industries, such as aerospace and their supplier firms, typically support and lobby for Republicans, whereas other industries, such as automotive and their supplier firms, generally support Democrats. National, state, and local elections impact businesses, with ongoing healthy debate concerning the pros and cons of each party’s agenda for business.

For industries and firms that depend heavily on government contracts or subsidies, political forecasts can be the most important part of an external audit. Changes in patent laws, antitrust legislation, tax rates, and lobbying activities can affect firms significantly. The increasing global interdependence among economies, markets, governments, and organizations makes it imperative that firms consider the possible impact of political variables on the formulation and implementation of competitive strategies.

Various countries worldwide are resorting to protectionism to safeguard their own industries. European Union (EU) nations, for example, have tightened their own trade rules and resumed subsidies for their own industries, while barring imports from certain other countries. The EU recently restricted imports of U.S. chicken and beef. India is increasing tariffs on foreign steel. Russia perhaps has instituted the most protectionist measures by raising tariffs on most imports and subsidizing its own exports. Despite these measures taken by other countries, the United States has largely refrained from “Buy American” policies and protectionist measures, although there are increased tariffs on French cheese and Italian water. Many economists say trade constraints will make it harder for global economic growth.

Local, state, and federal laws, as well as regulatory agencies and special-interest groups, can have a major impact on the strategies of small, large, for-profit, and nonprofit organizations. Many companies have altered or abandoned strategies in the past because of political or governmental actions. In the academic world, as state budgets have dropped in recent years, so too has state support for colleges and universities. Resulting from the decline in funds received from the state, many institutions of higher learning are doing more fund-raising on their own—naming buildings and classrooms, for example, for donors.

Some companies take public stands on political issues. For example, Starbucks’ recent support of same-sex marriage in its home state of Washington was praised by a number of prominent rights activists. Today, all states allow same-sex marriage. But the Seattle-based coffee chain’s outspoken opponents, such as the National Organization for Marriage (NOM), has vowed to make Starbucks (along with other companies that support same-sex marriage) pay a “price” for this stance. “Middle Eastern countries are hostile to lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights. So, for example, in Qatar, in the Middle East, we’ve begun working to make sure that there’s some price to be paid for this,” Brian Brown of the NOM said. “These are not countries that look kindly on same-sex marriage. And this is where Starbucks wants to expand, as well as India.”

Recently, CVS Caremark stopped selling tobacco products at its 7,600 stores, becoming the first U.S. drugstore chain to remove cigarettes from the store—and at the same time changed its corporate name to CVS Health. Nontobacco consumers and the medical community in general applauded the CVS announcement. With the announcement, CVS said its tobacco ban will result in the firm losing about $4 billion in annual sales. Euromonitor International reports that cigarette sales in the United States declined 31.3 percent from 2003 to 2013. However, smoking is still cited as the leading cause of preventable death in the country, killing more than 480,000 Americans per year. Within weeks after the CVS announcement, 24 states, Washington DC, and three U.S. territories sent coordinated letters to the CEOs of Walmart, Rite-Aid, Safeway, Kroger, and Walgreens, asking them to stop selling tobacco products.

In mid-2015, the United States normalized relations with Cuba, ending 54 years of hostility. This event represents an opportunity for numerous companies to do business with Cuba. On 7-20-15, Cuba raised its flag over its new embassy in Washington, D.C. For example, Carnival Corporation has won approval to begin cruising to Cuba and back, marking the first time in over 50 years that a cruise line can travel to and from Cuba.

A political debate still rages in the United States regarding sales taxes on the Internet. Walmart, Target, and other large retailers are pressuring state governments to collect sales taxes from Amazon.com. Big brick-and-mortar retailers are backing a coalition called the Alliance for Main Street Fairness, which is leading political efforts to change sales-tax laws in more than a dozen states. According to Walmart’s executive Raul Vazquez, “The rules today don’t allow brick-and-mortar retailers to compete evenly with online retailers, and that needs to be addressed.”

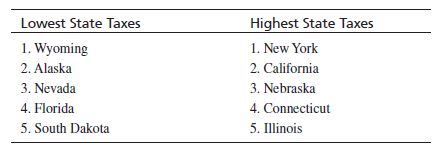

Federal, state, local, and foreign governments are major regulators, deregulators, subsidizers, employers, and customers of organizations. Political, governmental, and legal factors, therefore, can represent major opportunities or threats for both small and large organizations. Politicians decide on tax rates. State and local income taxes and property taxes impact where companies locate facilities and where people desire to live. The five states, in rank order, with the lowest overall state taxes, and the five states with the highest state taxes, are shown here.3

Regarding only state income taxes (rather than property, local, and sales taxes, too), seven states have zero (0.00) state income taxes: Texas, Nevada, Alaska, Florida, South Dakota, Washington, and Wyoming. States with the highest income tax are California (13.3%), Hawaii (11%), Oregon (9.90%), Minnesota (9.85%), Iowa (8.98%), and New Jersey (8.97%).

The extent that a state is unionized can be a significant political factor in strategic-planning decisions as related to manufacturing plant location and other operational matters. The size of U.S. labor unions has fallen sharply in the last decade as a result in large part of erosion of the U.S. manufacturing base. Organized public-sector labor issues are being debated in many state legislatures. Wisconsin, for example, recently passed a law eliminating most collectivebargaining rights for the state’s public-employee unions. That law sets a precedent that many other states may follow to curb union rights as a way to help state budgets become solvent. Ohio is close to passing a similar bill that will curb union rights for 400,000 public workers. Among states, New York continues to have the highest union membership rate (24.1 percent) and North Carolina has the lowest rate (2.9 percent).

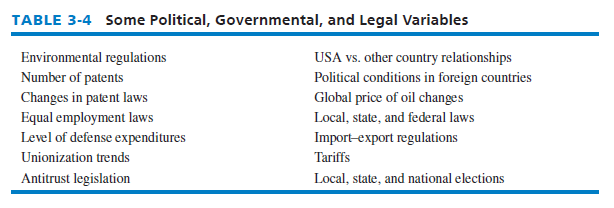

Some political, governmental, and legal variables that can represent key opportunities or threats to organizations are provided in Table 3-4, but in stating these for a particular company, the factors should be both quantitative and actionable.

4. Technological Forces

A variety of new technologies such as the Internet of Things, 3D printing, the cloud, mobile devices, biotech, analytics, autotech, robotics, and artificial intelligence are fueling innovation in many industries, and impacting strategic-planning decisions. Businesses are using mobile technologies and applications to better determine customer trends and employing advanced analytics data to make enhanced strategy decisions. The vast increase in the amount of data coming from mobile devices is driving the development of advanced analytics applications. In fact, by 2018, machine-to-machine devices ranging from wearable Web access devices and utility meters and sensors in cars will account for 35 percent of global Internet network-connected devices, up from 18.6 percent today.4 A primary reason that Cisco Systems has recently entered the data analytics business is that sales of hardware, software, and services connected to the Internet of Things is expected to increase to $7.1 billion by 2020 from about $2.0 billion in 2015.

Rapid technological advances in mobile and electronic banking have led banks to close branch offices at dramatically increasing rates in the United States. The total number of branch locations has dropped below 90,000, the lowest total number in the United States in a decade. Too offset closing branch offices, U.S. banks are ramping up mobile and online services, such as allowing customers to make deposits simply by snapping photos of checks with smartphones and emailing them. Many banks now allow customers to transfer money to other customers via smartphones. At Bank of America, for example, nearly 15 percent of all checks deposited by customers come from snapping pictures on smartphones or tablet computers. Not a single state in the United States reported an increase in the number of branch bank locations in recent years.5 Florida leads all states in branch bank closures, followed by Pennsylvania. Technology is rapidly changing the competitive landscape in banking, and many other industries characterized by brick-and-mortar stores.

Monitoring online reviews about your business, large or small, has become a burdensome but an essential task, especially given emergence of social-media channels, such as Twitter, that empowers opinionated customers. Research is clear that benign neglect of a company’s online reputation could quickly hurt sales, especially given the new normal behavior of customers consulting their smartphones for even the smallest of purchases.6

A number of organizations are establishing two positions in their firms: chief information officer (CIO) and chief technology officer (CTO), reflecting the growing importance of information technology (IT) in strategic management. A CIO and CTO work together to ensure that information needed to formulate, implement, and evaluate strategies is available where and when it is needed. These individuals are responsible for developing, maintaining, and updating a company’s information database. The CIO is more a manager, managing the firm’s relationship with stakeholders; the CTO is more a technician, focusing on technical issues such as data acquisition, data processing, decision-support systems, and software and hardware acquisition.

Global cybersecurity spending by critical infrastructure industries exceeds $50 billion annually, and is rising more than 10 percent annually.7 Security is a major concern for all businesses, yet complete security is something most businesses cannot financially afford to install. Hackers recently stole 40 million of Target Corporation’s customers’ credit- and debit-card numbers, along with passcodes and passwords. Building firewalls and triplicate systems can be expensive. Similarly, J.P. Morgan reported that 76 million of their customers’ contact information was recently stolen in a cybersecurity breach. Sony, too, was recently a victim of a massive cyberattack. Even the federal government employee databanks were recently hacked, reportedly by some entities in China.

Results of technological advancements are varied, as shown in the following list:

- They represent major opportunities and threats that must be considered in formulating strategies.

- They can dramatically affect organizations’ products, services, markets, suppliers, distributors, competitors, customers, manufacturing processes, marketing practices, and competitive position.

- They can create new markets, result in a proliferation of new and improved products, change the relative competitive cost positions in an industry, and render existing products and services obsolete.

- They can reduce or eliminate cost barriers between businesses, create shorter production runs, create shortages in technical skills, and result in changing values and expectations of employees, managers, and customers.

- They can create new competitive advantages that are more powerful than existing advantages.

No company or industry today is insulated against emerging technological developments. In high-tech industries, identification and evaluation of key technological opportunities and threats can be the most important part of the external strategic-management audit.

5. Competitive Forces

An important part of an external audit is identifying rival firms and determining their strengths, weaknesses, capabilities, opportunities, threats, objectives, and strategies. George Salk stated, “If you’re not faster than your competitor, you’re in a tenuous position, and if you’re only half as fast, you’re terminal.”

Collecting and evaluating information on competitors is essential for successful strategy formulation. Identifying major competitors is not always easy because many firms have divisions that compete in different industries. Many multidivisional firms do not provide sales and profit information on a divisional basis for competitive reasons. Also, privately held firms do not publish any financial or marketing information. Addressing questions about competitors, such as those presented in Table 3-5, is important in performing an external audit.

Competition in virtually all industries is intense—and sometimes cutthroat. For example, Walgreens and CVS pharmacies are located generally across the street from each other and battle each other every day on price and customer service. Most automobile dealerships also are located close to each other. Dollar General, Dollar Tree, and Family Dollar compete intensely on price to attract customers away from each other and away from Walmart and Target.

Seven characteristics describe the most competitive companies:

- Strive to continually increase market share.

- Use the vision/mission as a guide for all decisions.

- Realize that the adage “If it’s not broke, don’t fix it” has been replaced by “Whether it’s broke or not, fix it”; in other words, continually strive to improve everything about the firm.

- Continually adapt, innovate, improve—especially when the firm is successful.

- Strive to grow through acquisition whenever possible.

- Hire and retain the best employees and managers possible.

- Strive to stay cost-competitive on a global basis.8

Competitive intelligence (CI), as formally defined by the Society of Competitive Intelligence Professionals (SCIP), is a systematic and ethical process for gathering and analyzing information about the competition’s activities and general business trends to further a business’s own goals (SCIP website). Good competitive intelligence in business, as in the military, is one of the keys to success. The more information and knowledge a firm can obtain about its competitors, the more likely the firm can formulate and implement effective strategies. Major competitors’ weaknesses can represent external opportunities; major competitors’ strengths may represent key threats.

Various legal and ethical ways to obtain competitive intelligence include the following:

- Hire top executives from rival firms.

- Reverse engineer rival firms’ products.

- Use surveys and interviews of customers, suppliers, and distributors.

- Conduct drive-by and on-site visits to rival firm operations.

- Search online databases.

- Contact government agencies for public information about rival firms.

- Systematically monitor relevant trade publications, magazines, and newspapers.

Information gathering from employees, managers, suppliers, distributors, customers, creditors, and consultants also can make the difference between having superior or just average intelligence and overall competitiveness. The Fuld website explains that competitive intelligence is not the following:

Is not spying

Is not a crystal ball

Is not a simple Google search

Is not one-size-fits-all

Is not useful if no one is listening

Is not a job for one, smart person

Is not a fad

Is not driven by software or technology

Is not based on internal assumptions about the market

Is not a spreadsheet.9

The three basic objectives of a CI program are (1) to provide a general understanding of an industry and its competitors, (2) to identify areas in which competitors are vulnerable and to assess the impact strategic actions would have on competitors, and (3) to identify potential moves that a competitor might make that would endanger a firm’s position in the market.10 Competitive information is equally applicable for strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation decisions. An effective CI program allows all areas of a firm to access consistent and verifiable information in making decisions. All members of an organization—from the CEO to custodians—are valuable intelligence agents and should feel themselves to be a part of the CI process. Special characteristics of a successful CI program include flexibility, usefulness, timeliness, and cross-functional cooperation.

Competitive intelligence is not corporate espionage; after all, 95 percent of the information a company needs to make strategic decisions is available and accessible to the public. Sources of competitive information include trade journals, want ads, newspaper articles, and government filings, as well as customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors themselves, and the Internet. Unethical tactics such as bribery, wiretapping, and computer hacking should never be used to obtain information. All the information a company needs can be collected without resorting to unethical tactics.

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

it is a remarkable web site