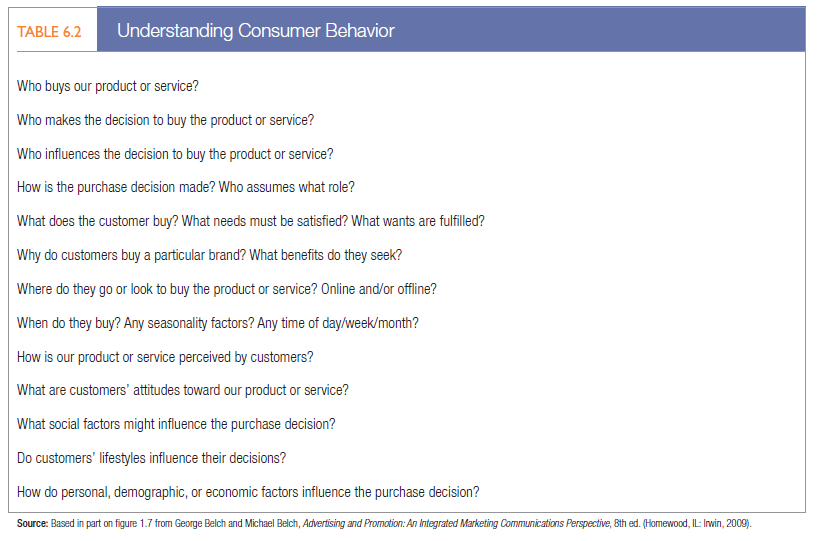

The basic psychological processes we’ve reviewed play an important role in consumers’ actual buying decisions. Table 6.2 provides a list of some key consumer behavior questions marketers should ask in terms of who, what, when, where, how, and why.

Smart companies try to fully understand customers’ buying decision process—all the experiences in learning, choosing, using, and even disposing of a product. Marketing scholars have developed a “stage model” of the process (see Figure 6.4). The consumer typically passes through five stages: problem recognition, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase decision, and postpurchase behavior.

Clearly, the buying process starts long before the actual purchase and has consequences long afterward.52 Some consumers passively shop and may decide to make a purchase from unsolicited information they encounter in the normal course of events.53 Recognizing this fact, marketers must develop activities and programs that reach consumers at all decision stages. Consider how Procter & Gamble launched a new CoverGirl “Smokey Eye Look” makeup kit.54

P&G COVERGIRL To create awareness at product launch, P&G sent makeup bloggers “Makeup Master” kits with packs of mascara, eyeliner, and eye shadow along with application instructions, blogging tips, product photographs, and a CoverGirl-emblazoned director’s chair before the product was available in stores. At stores, CoverGirl created attention and interest with live product demonstrations, co-branded print ads with Walmart, and cardboard trays displaying product features and the product kits themselves. After they bought, purchasers were encouraged via Facebook and other online campaigns to provide feedback and write reviews to influence others. The brand’s Facebook page featured testimonies from celebrities Ellen DeGeneres and Sofia Vergara. CoverGirl is one of P&G’s most digitally supported brands, recognizing the high level of consumer involvement and the need to stay up to date. P&G is also supporting CoverGirl via mobile marketing through targeted ads and a microsite with experts’ tips and video on proper application.

Consumers don’t always pass through all five stages—they may skip or reverse some. When you buy your regular brand of toothpaste, you go directly from the need to the purchase decision, skipping information search and evaluation. The model in Figure 6.4 provides a good frame of reference, however, because it captures the full range of considerations that arise when a consumer faces a highly involving or new purchase. Later in the chapter, we will consider other ways consumers make decisions that are less calculated.

1. PROBLEM RECOGNITION

The buying process starts when the buyer recognizes a problem or need triggered by internal or external stimuli. With an internal stimulus, one of the person’s normal needs—hunger, thirst, sex—rises to a threshold level and becomes a drive. A need can also be aroused by an external stimulus. A person may admire a friend’s new car or see a television ad for a Hawaiian vacation, which inspires thoughts about the possibility of making a purchase.

Marketers need to identify the circumstances that trigger a particular need by gathering information from a number of consumers. They can then develop marketing strategies that spark consumer interest. Particularly for discretionary purchases such as luxury goods, vacation packages, and entertainment options, marketers may need to increase consumer motivation so a potential purchase gets serious consideration.

2. INFORMATION SEARCH

Surprisingly, consumers often search for only limited information. Surveys have shown that for durables, half of all consumers look at only one store, and only 30 percent look at more than one brand of appliances. We can distinguish between two levels of engagement in the search. The milder search state is called heightened attention. At this level a person simply becomes more receptive to information about a product. At the next level, the person may enter an active information search: looking for reading material, phoning friends, going online, and visiting stores to learn about the product.

Marketers must understand what type of information consumers seek—or are at least receptive to—at different times and places.55 Unilever, in collaboration with Kroger, the largest U.S. retail grocery chain, has learned that meal planning goes through a three-step process: discussion of meals and what might go into them; choice of exactly what will go into a particular meal, and finally purchase. Mondays turn out to be critical days for planning for the week. Conversations at breakfast time tend to focus on health, but later in the day, at lunch, discussion centers more on how meals could possibly be repurposed for leftovers.56

INFORMATION SOURCES Major information sources to which consumers will turn fall into four groups:

- Personal. Family, friends, neighbors, acquaintances

- Commercial. Advertising, Web sites, e-mails, salespersons, dealers, packaging, displays

- Public. Mass media, social media, consumer-rating organizations

- Experiential. Handling, examining, using the product

The relative amount of information and influence of these sources vary with the product category and the buyer’s characteristics. Generally speaking, although consumers receive the greatest amount of information about a product from commercial—that is, marketer-dominated—sources, the most effective information often comes from personal or experiential sources or public sources that are independent authorities.57

Each source performs a different function in influencing the buying decision. Commercial sources normally perform an information function, whereas personal sources perform a legitimizing or evaluation function. For example, physicians often learn of new drugs from commercial sources but turn to other doctors for evaluations. Many consumers alternate between going online and offline (in stores) to learn about products and brands.

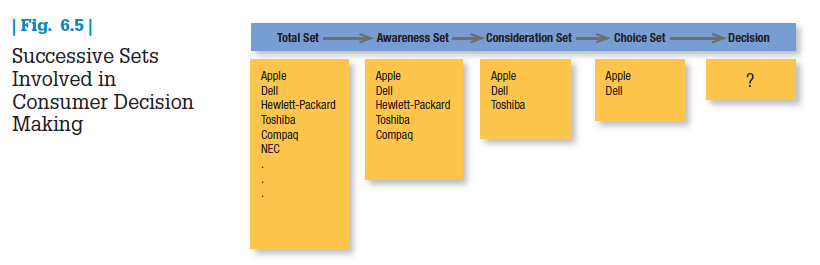

SEARCH DYNAMICS By gathering information, the consumer learns about competing brands and their features. The first box in Figure 6.5 shows the total set of brands available. The individual consumer will come to know a subset of these, the awareness set. Only some, the consideration set, will meet initial buying criteria. As the consumer gathers more information, just a few, the choice set, will remain strong contenders. The consumer makes a final choice from these.58

Marketers need to identify the hierarchy of attributes that guide consumer decision making in order to understand different competitive forces and how these various sets get formed. This process of identifying the hierarchy is called market partitioning. Years ago, most car buyers first decided on the manufacturer and then on one of its car divisions (brand-dominant hierarchy). A buyer might favor General Motors cars and, within this set, Chevrolet. Today, many buyers decide first on the nation or nations from which they want to buy a car (nation-dominant hierarchy). Buyers may first decide they want to buy a German car, then Audi, and then the A4 model of Audi.

The hierarchy of attributes also can reveal customer segments. Buyers who first decide on price are price dominant; those who first decide on the type of car (sports, passenger, hybrid) are type dominant; those who choose the brand first are brand dominant. Type/price/brand-dominant consumers make up one segment; quality/service/type buyers make up another. Each may have distinct demographics, psychographics, and mediagraphics and different awareness, consideration, and choice sets.

Figure 6.5 makes it clear that a company must strategize to get its brand into the prospect’s awareness, consideration, and choice sets. If a food store owner arranges yogurt first by brand (such as Dannon and Yoplait) and then by flavor within each brand, consumers will tend to select their flavors from the same brand. However, if all the strawberry yogurts are together, then all the vanilla, and so forth, consumers will probably choose the flavors they want first and then choose the brand name they want for that particular flavor.

Search behavior can vary online, in part because of the manner in which product information is presented. For example, product alternatives may be presented in order of their predicted attractiveness for the consumer. Consumers may then choose not to search as extensively as they would otherwise.59

The company must also identify the other brands in the consumer’s choice set so that it can plan the appropriate competitive appeals. In addition, marketers should identify the consumer’s information sources and evaluate their relative importance. Asking consumers how they first heard about the brand, what information came later, and the relative importance of the different sources will help the company prepare effective communications for the target market.

3. EVALUATION OF ALTERNATIVES

How does the consumer process competitive brand information and make a final value judgment? No single process is used by all consumers or by one consumer in all buying situations. There are several processes, and the most current models see the consumer forming judgments largely on a conscious and rational basis.

Some basic concepts will help us understand consumer evaluation processes. First, the consumer is trying to satisfy a need. Second, the consumer is looking for certain benefits from the product solution. Third, the consumer sees each product as a bundle of attributes with varying abilities to deliver the benefits. The attributes of interest to buyers vary by product—for example:

- Hotels—Location, cleanliness, atmosphere, price

- Mouthwash—Color, effectiveness, germ-killing capacity, taste/flavor, price

- Tires—Safety, tread life, ride quality, price

Consumers will pay the most attention to attributes that deliver the sought-after benefits. We can often segment the market for a product according to attributes and benefits important to different consumer groups.

BELIEFS AND ATTiTUDES Through experience and learning, people acquire beliefs and attitudes. These in turn influence buying behavior. A belief is a descriptive thought that a person holds about something. Just as important are attitudes, a person’s enduring favorable or unfavorable evaluations, emotional feelings, and action tendencies toward some object or idea. People have attitudes toward almost everything: religion, politics, clothes, music, or food.

Attitudes put us into a frame of mind: liking or disliking an object, moving toward or away from it. They lead us to behave in a fairly consistent way toward similar objects. Because attitudes economize on energy and thought, they can be very difficult to change. As a general rule, a company is well advised to fit its product into existing attitudes rather than try to change attitudes. If beliefs and attitudes become too negative, however, more active steps may be necessary.

EXPECTANCY-VALUE MODEL The consumer arrives at attitudes toward various brands through an attribute-evaluation procedure, developing a set of beliefs about where each brand stands on each attribute.60 The expectancy-value model of attitude formation posits that consumers evaluate products and services by combining their brand beliefs—the positives and negatives—according to importance.

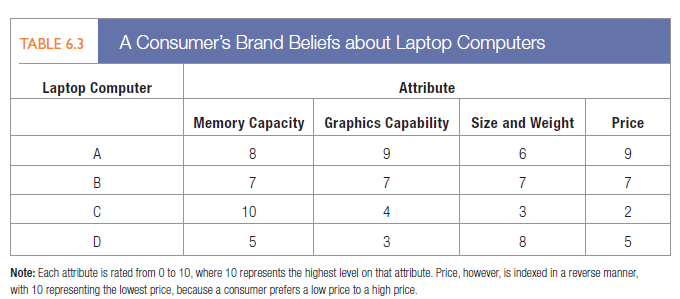

Suppose Linda has narrowed her choice set to four laptops (A, B, C, and D). Assume she’s interested in four attributes: memory capacity, graphics capability, size and weight, and price. Table 6.3 shows her beliefs about how each brand rates on the four attributes. If one computer dominated the others on all the criteria, we could predict that Linda would choose it. But, as is often the case, her choice set consists of brands that vary in their appeal. If Linda wants the best memory capacity, she should buy C; if she wants the best graphics capability, she should buy A; and so on.

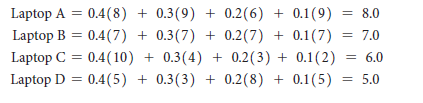

If we knew the weights Linda attaches to the four attributes, we could more reliably predict her choice. Suppose she assigned 40 percent of the importance to the laptop’s memory capacity, 30 percent to graphics capability, 20 percent to size and weight, and 10 percent to price. To find Linda’s perceived value for each laptop according to the expectancy-value model, we multiply her weights by her beliefs about each computer’s attributes. This computation leads to the following perceived values:

An expectancy-model formulation predicts that Linda will favor laptop A, which (at 8.0) has the highest perceived value.61

Suppose most laptop buyers form their preferences the same way. Knowing this, the marketer of laptop B, for example, could apply the following strategies to stimulate greater interest in brand B:

- Redesign the laptop. This technique is called real repositioning.

- Alter beliefs about the brand. Attempting to alter beliefs about the brand is called psychological repositioning.

- Alter beliefs about competitors’ brands. This strategy, called competitive depositioning, makes sense when buyers mistakenly believe a competitor’s brand is higher quality than it actually is.

- Alter the importance weights. The marketer could try to persuade buyers to attach more importance to the attributes in which the brand excels.

- Call attention to neglected attributes. The marketer could draw buyers’ attention to neglected attributes, such as styling or processing speed.

- Shift the buyer’s ideals. The marketer could try to persuade buyers to change their ideal levels for one or more attributes.62

4. PURCHASE DECISION

In the evaluation stage, the consumer forms preferences among the brands in the choice set and may also form an intention to buy the most preferred brand. In executing a purchase intention, the consumer may make as many as five subdecisions: brand (brand A), dealer (dealer 2), quantity (one computer), timing (weekend), and payment method (credit card).

NONCOMPENSATORY MODELS OF CONSUMER CHOICE The expectancy-value model is a compensatory model, in that perceived good things about a product can help to overcome perceived bad things. But consumers often take “mental shortcuts” called heuristics or rules of thumb in the decision process.

With noncompensatory models of consumer choice, positive and negative attribute considerations don’t necessarily net out. Evaluating attributes in isolation makes decision making easier for a consumer, but it also increases the likelihood that she would have made a different choice if she had deliberated in greater detail. We highlight three choice heuristics here.63

- Using the conjunctive heuristic, the consumer sets a minimum acceptable cutoff level for each attribute and chooses the first alternative that meets the minimum standard for all attributes. For example, if Linda decided all attributes had to rate at least 5, she would choose laptop B.

- With the lexicographic heuristic, the consumer chooses the best brand on the basis of its perceived most important attribute. With this decision rule, Linda would choose laptop C.

- Using the elimination-by-aspects heuristic, the consumer compares brands on an attribute selected probabilistically—where the probability of choosing an attribute is positively related to its importance—and eliminates brands that do not meet minimum acceptable cutoffs.

Our brand or product knowledge, the number and similarity of brand choices and time pressures present, and the social context (such as the need for justification to a peer or boss) all may affect whether and how we use choice heuristics.

Consumers don’t necessarily use only one type of choice rule. For example, they might use a noncompensatory decision rule such as the conjunctive heuristic to reduce the number of brand choices to a more manageable number and then evaluate the remaining brands.

One reason for the runaway success of the Intel Inside campaign in the 1990s was that it made the brand the first cutoff for many consumers—they would buy only a personal computer that had an Intel microprocessor. Leading personal computer makers at the time, such as IBM, Dell, and Gateway, had no choice but to support Intel’s marketing efforts.

A number of factors will determine the manner in which consumers form evaluations and make choices. University of Chicago professors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein show how marketers can influence consumer decision making through what they call the choice architecture—the environment in which decisions are structured and buying choices are made.

According to these researchers, in the right environment, consumers can be given a “nudge” via some small feature in the environment that attracts attention and alters behavior. They maintain Nabisco is employing a smart choice architecture by offering 100-calorie snack packs, which have solid profit margins, while nudging consumers to make healthier choices.64

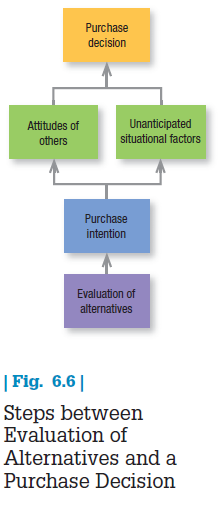

INTERVENING FACTORS Even if consumers form brand evaluations, two general factors can intervene between the purchase intention and the purchase decision (see Figure 6.6). The first factor is the attitudes of others. The influence on us of another person’s attitude depends on two things: (1) the intensity of the other person’s negative attitude toward our preferred alternative and (2) our motivation to comply with the other person’s wishes.65 The more intense the other person’s negativism and the closer he or she is to us, the more we will adjust our purchase intention. The converse is also true.

Related to the attitudes of others is the role played by infomediaries’ evaluations: Consumer Reports, which provides unbiased expert reviews of all types of products and services; J. D. Power, which provides consumer-based ratings of cars, financial services, and travel products and services; professional movie, book, and music reviewers; customer reviews of books and music on such sites as Amazon.com; and the increasing number of chat rooms, bulletin boards, blogs, and other online sites like Angie’s List where people discuss products, services, and companies.66

Consumers are undoubtedly influenced by these external evaluations, as evidenced by the runaway success of the movie Ted.67

TED With a modest production budget of $50 million, the R-rated comedy Ted became a summer blockbuster in 2012, eventually grossing more than a staggering $530 million worldwide, thanks to favorable reviews by critics and moviegoers and a carefully constructed online marketing campaign. Edgy videos and a Twitter feed with raunchy advice from Ted, the often-crude teddy bear star, created much online buzz. Fans of the movie’s Facebook page approached 3 million, Twitter followers reached 400,000, and a “Talking Ted” iPhone app was downloaded 3.5 million times. Universal Pictures’ marketing campaign also included several different theater trailers to attract different types of audiences. Social media targeted fans of the Family Guy television show, whose creator, Seth McFarlane, directed Ted and provided the voice of the title character. After the first trailer went online, the studio picked up much online chatter with a song, “Thunder Buddies,” that the other star of the movie, Mark Wahlberg, sang to Ted while in bed. To capitalize on the buzz, the studio put out a remixed version of the song on the movie’s Web site, e-cards with lyrics on Facebook, Thunder Buddy pajamas from CafePress.com, and a 30-second video clip of the song.

The second factor is unanticipated situational factors that may erupt to change the purchase intention. Linda might lose her job before she purchases a laptop, some other purchase might become more urgent, or a store salesperson may turn her off. As Chapter 15 discusses, much marketing occurs at the point of purchase: online or in the store.

Preferences and even purchase intentions are not completely reliable predictors of purchase behavior. A consumer’s decision to modify, postpone, or avoid a purchase decision is heavily influenced by one or more types of perceived risk6

- Functional risk—The product does not perform to expectations.

- Physical risk—The product poses a threat to the physical well-being or health of the user or others.

- Financial risk—The product is not worth the price paid.

- Social risk—The product results in embarrassment in front of others.

- Psychological risk—The product affects the mental well-being of the user.

- Time risk—The failure of the product results in an opportunity cost of finding another satisfactory product.

The degree of perceived risk varies with the amount of money at stake, the amount of attribute uncertainty, and the level of consumer self-confidence. Consumers develop routines for reducing the uncertainty and negative consequences of risk, such as avoiding decisions, gathering information from friends, and developing preferences for national brand names and warranties. Marketers must understand the factors that provoke a feeling of risk in consumers and provide information and support to reduce it.

5. POSTPURCHASE BEHAVIOR

After the purchase, the consumer might experience dissonance from noticing certain disquieting features or hearing favorable things about other brands and will be alert to information that supports his or her decision. Marketing communications should supply beliefs and evaluations that reinforce the consumer’s choice and help him or her feel good about the brand. The marketer’s job therefore doesn’t end with the purchase. Marketers must monitor postpurchase satisfaction, postpurchase actions, and postpurchase product uses and disposal.

POSTPURCHASE SATiSFACTION Satisfaction is a function of the closeness between expectations and the product’s perceived performance.69 If performance falls short of expectations, the consumer is disappointed; if it meets expectations, the consumer is satisfied; if it exceeds expectations, the consumer is delighted. These feelings make a difference in whether the customer buys the product again and talks favorably or unfavorably about it to others.

The larger the gap between expectations and performance, the greater the dissatisfaction. Here the consumer’s coping style comes into play. Some consumers magnify the gap when the product isn’t perfect and are highly dissatisfied; others minimize it and are less dissatisfied.

POSTPURCHASE ACTIONS A satisfied consumer is more likely to purchase the product again and will also tend to say good things about the brand to others. Dissatisfied consumers may abandon or return the product. They may seek information that confirms its high value. They may take public action by complaining to the company, going to a lawyer, or complaining directly to other groups (such as business, private, or government agencies) or to many others online. Private actions include deciding to stop buying the product (exit option) or warning friends (voice option).70

Chapter 5 described CRM programs designed to build long-term brand loyalty. Postpurchase communications to buyers have been shown to result in fewer product returns and order cancellations. Computer companies, for example, can send a letter to new owners congratulating them on having selected a fine new tablet computer. They can place ads showing satisfied brand owners. They can solicit customer suggestions for improvements and list the location of available services. They can write intelligible instruction booklets. They can send owners e-mail updates describing new tablet applications. In addition, they can provide good channels for speedy redress of customer grievances.

POSTPURCHASE USES AND DiSPOSAL Marketers should also monitor how buyers use and dispose of the product (Figure 6.7). A key driver of sales frequency is product consumption rate—the more quickly buyers consume a product, the sooner they may be back in the market to repurchase it.

Consumers may fail to replace some products soon enough because they overestimate product life.71 One strategy to speed replacement is to tie the act of replacing the product to a certain holiday, event, or time of year (such as promoting changing the batteries in smoke detectors when Daylight Savings ends).

Another strategy is to provide consumers with better information about either (1) the time they first used the product or need to replace it or (2) its current level of performance. Batteries have built-in gauges that show how much power they have left; razors have color in their lubricating strips to indicate when blades may be worn; and so on. Perhaps the simplest way to increase usage is to learn when actual usage is lower than recommended and persuade customers that more regular usage has benefits, overcoming potential hurdles.

If consumers throw the product away, the marketer needs to know how they dispose of it, especially if—like batteries, beverage containers, electronic equipment, and disposable diapers—it can damage the environment. There also may be product opportunities in disposed products: Air Salvage International is the largest plane dismantler in Europe and a major player in the booming secondhand market for aircraft parts, which totaled $2.5 billion from 2009 to 2011; vintage clothing shops, such as Savers, resell 2.5 billion pounds of used clothing annually; Diamond Safety buys finely ground used tires and then makes and sells playground covers and athletic fields.72

6. MODERATING EFFECTS ON CONSUMER DECISION MAKING

The path by which a consumer moves through the decision-making stages depends on several factors, including the level of involvement and extent of variety seeking.

LOW-INVOLVEMENT CONSUMER DECISION MAKING The expectancy-value model assumes a high level of consumer involvement, or engagement and active processing the consumer undertakes in responding to a marketing stimulus.

Richard Petty and John Cacioppo’s elaboration likelihood model, an influential model of attitude formation and change, describes how consumers make evaluations in both low- and high-involvement circumstances.73 There are two means of persuasion in their model: the central route, in which attitude formation or change stimulates much thought and is based on the consumer’s diligent, rational consideration of the most important product information; and the peripheral route, in which attitude formation or change provokes much less thought and results from the consumer’s association of a brand with either positive or negative peripheral cues. Peripheral cues for consumers include a celebrity endorsement, a credible source, or any object that generates positive feelings.

Consumers follow the central route only if they possess sufficient motivation, ability, and opportunity. In other words, they must want to evaluate a brand in detail, have the necessary brand and product or service knowledge in memory, and have sufficient time and the proper setting. If any of those factors is lacking, consumers tend to follow the peripheral route and consider less central, more extrinsic factors in their decisions.

We buy many products under conditions of low involvement and without significant brand differences. Consider salt. If consumers keep reaching for the same brand in this category, it may be out of habit, not strong brand loyalty. Evidence suggests we have low involvement with most low-cost, frequently purchased products.

Marketers use four techniques to try to convert a low-involvement product into one of higher involvement. First, they can link the product to an engaging issue, as when Crest linked its toothpaste to cavity prevention. Second, they can link the product to a personal situation—for example, fruit juice makers began to include vitamins such as calcium to fortify their drinks. Third, they might design advertising to trigger strong emotions related to personal values or ego defense, as when cereal makers began to advertise to adults the heart-healthy nature of cereals and the importance of living a long time to enjoy family life. Fourth, they might add an important feature—for example, when GE lightbulbs introduced “Soft White” versions. These strategies at best raise consumer involvement from a low to a moderate level; they do not necessarily propel the consumer into highly involved buying behavior.

If consumers will have low involvement with a purchase decision regardless of what the marketer can do, they are likely to follow the peripheral route. Marketers must give consumers one or more positive cues to justify their brand choice, such as frequent ad repetition, visible sponsorships, and vigorous PR to enhance brand familiarity. Other peripheral cues that can tip the balance in favor of the brand include a beloved celebrity endorser, attractive packaging, and an appealing promotion.

VARIETY-SEEKING BUYING BEHAVIOR Some buying situations are characterized by low involvement but significant brand differences. Here consumers often do a lot of brand switching. Think about cookies. The consumer has some beliefs about cookies, chooses a brand without much evaluation, and evaluates the product during consumption. Next time, the consumer may reach for another brand out of a desire for a different taste. Brand switching occurs for the sake of variety rather than from dissatisfaction.

The market leader and the minor brands in this product category have different marketing strategies. The market leader will try to encourage habitual buying behavior by dominating the shelf space with a variety of related product versions, avoiding out-of-stock conditions, and sponsoring frequent reminder advertising. Challenger firms will encourage variety seeking by offering lower prices, deals, coupons, free samples, and advertising that tries to break the consumer’s purchase and consumption cycle and presents reasons for trying something new.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Howdy! I simply would like to give you a big thumbs up for the excellent information you have right here on this post. I’ll be coming back to your site for more soon.