In the constructionist view, as the word suggests, meaning is not discovered but constructed. Meaning does not inhere in the object, merely waiting for someone to come upon it. As writers like Merleau- Ponty have pointed out very tellingly, the world and objects in the world are indeterminate. They may be pregnant with potential meaning, but actual meaning emerges only when consciousness engages with them. How, such thinkers ask, can there be meaning without a mind?

Accepting that the world we experience, prior to our experience of it, is without meaning does not come easy. What the ‘commonsense’ view commends to us is that the tree standing before us is a tree. It has all the meaning we ascribe to a tree. It would be a tree, with that same meaning, whether anyone knew of its existence or not. We need to remind ourselves here that it is human beings who have construed it as a tree, given it the name, and attributed to it the associations we make with trees. It may help if we recall the extent to which those associations differ even within the same overall culture. ‘Tree’ is likely to bear quite different connotations in a logging town, an artists’ setdement and a treeless slum.

What constructionism claims is that meanings are constructed by human beings as they engage with the world they are interpreting. Before there were consciousnesses on earth capable of interpreting the world, the world held no meaning at all.

You may object that you cannot imagine a time when nothing existed in any phenomenal form. Were there not volcanoes, and dust-storms and starlight long before there was any life on Earth? Did not the sun rise in the East and set in the West? Did not water flow downhill, and light travel faster than sound? The answer is that if you had been there, that is indeed the way the phenomena would have appeared to you. But you were not there: no one was. And because no one was there, there was not —at this mindless stage of history—anything that counted as a volcano, or a dust-storm, and so on. I am not suggesting that the world had no substance to it whatsoever. We might say, perhaps, that it consisted of ‘worldstuff’. But the properties of this worldstuff had yet to be represented by a mind. (Humphrey 1993, p. 17)

From the constructionist viewpoint, therefore, meaning (or truth) cannot be described simply as ‘objective’. By the same token, it cannot be described simply as ‘subjective’. Some researchers describing themselves as constructionist talk as if meanings are created out of whole cloth and simply imposed upon reality. This is to espouse an out-and-out subjectivism and to reject both the existentialist concept of humans as beings-in-the-world and the phenomenological concept of intentionality. There are strong threads within structuralist, post-structuralist and postmodernist thought espousing a subjectivist epistemology but constructionism is different. According to constructionism, we do not create meaning. We construct meaning. We have something to work with. What we have to work with is the world and objects in the world.

As Heidegger and Merleau-Ponty repeatedly state, the world is ‘always already there’. The world and objects in the world may be in themselves meaningless; yet they are our partners in the generation of meaning and need to be taken seriously. It is surely important, and liberating, to distinguish theory consistent with experienced reality from theory that is not. Objectivity and subjectivity need to be brought together and held together indissolubly. Constructionism does precisely that.

In this respect, constructionism mirrors the concept of intentionality. Intentionality is a notion that phenomenology borrowed from Scholastic philosophy and in its turn has shared with other orientations. It was the renowned nineteenth-century psychologist and philosopher Franz Brentano who invoked the Scholastic concept of intentionality. Brentano’s student and acknowledged founder of phenomenology Edmund Husserl went on to make it the pivotal concept of his philosophy.

Brentano recalls (1973, p. 88) that, in medieval philosophy, all mental phenomena are described as having ‘reference to a content, direction toward an object’. Consciousness, in other words, is always consciousness of something. ‘In presentation something is presented, in judgment something is affirmed or denied, in love loved, in hate hated, in desire desired and so on.’

It is important to note that ‘intentionality’ and ‘intentional’ as used here have nothing to do with purpose or deliberation. The root stem of these words is the Latin tendere, which means ‘to tend’—in the sense of ‘moving towards’ or ‘directing oneself to’. Here ‘in-tending’ is not about choosing or planning but about reaching out into (just as ‘ex-tending’ is about reaching out from). Intentionality means referentiality, relatedness, directedness, ‘aboutness’.

The basic message of intentionality is straightforward enough. When the mind becomes conscious of something, when it ‘knows’ something, it reaches out to, and into, that object. In contrast to other epistemologies at large towards the end of the nineteenth century, intentionality posits a quite intimate and very active relationship between the conscious subject and the object of the subject’s .consciousness. Consciousness is directed towards the object; the object is shaped by consciousness. As Lyotard expresses it:

There is thus no answer to the question whether philosophy must begin with the object (realism) or with the ego (idealism). The very idea of phenomenology puts this question out of play: consciousness is always consciousness of, and there is no object which is not an object for. There is no immanence of the object to consciousness unless one corelatively assigns the object a rational meaning, without which the object would not be an object for. Concept or meaning is not exterior to Being; rather, Being is immediately concept in itself, and the concept is Being for itself. (1991, p. 65)

Later phenomenologists, working within the context of an existentialist philosophy, make the process far less cerebral. Not only is consciousness intentional, but human beings in their totality are intentionally related to their world. Human being means being-in-the- world. In existentialist terms, intentionality is a radical interdependence of subject and world.

Because of the essential relationship that human experience bears to its object, no object can be adequately described in isolation from the conscious being experiencing it, nor can any experience be adequately described in isolation from its object. Experiences do not constitute a sphere of subjective reality separate from, and in contrast to, the objective realm of the external world—as Descartes’ famous ‘split’ between mind and body, and thereby between mind and world, would lead us to imagine. In the way of thinking to which intentionality introduces us, such a dichotomy between the subjective and the objective is untenable. Subject and object, distinguishable as they are, are always united. It is this insight that is captured in the term ‘intentionality’.

To embrace the notion of intentionality is to reject objectivism. Equally, it is to reject subjectivism. What intentionality brings to the fore is interaction between subject and object. The image evoked is that of humans engaging with their human world. It is in and out of this interplay that meaning is bom.

It may be helpful to consider what literary critic and linguistics exponent Stanley Fish has to say. In a well-known essay (1990), Fish recalls a summer program in which he was teaching two courses. One explored the relationship between linguistics and literary criticism. The other was a course in English religious poetry. The sessions for both courses were held in the same classroom and they followed one after the other.

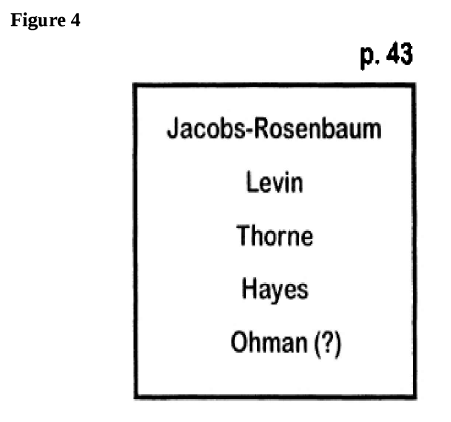

One morning, when the students in the first course had left the room, Fish looked at a list of names he had written on the blackboard. It was the assignment he had set for the students. The people listed were authors whose works the students were expected to consult before the next class. One of the names listed had a question mark after it, because Fish was not sure whether it was spelled correcdy.

Fish went to the board, drew a frame around the names and wrote ‘p. 43’ above the frame. When the students in the second course filed into the room for their class, what confronted them on the blackboard was what we see in Figure 4.

Fish began this second class for the day by drawing the students’ attention to the list of names. He informed them that it was a religious poem of the kind they had been studying and invited them to interpret it.

The students were equal to the task. The first student to speak commented on the shape of the poem. The poem was a hieroglyph, he surmised, but was it in the shape of an altar or a cross? After this promising start, other students were not slow to follow suit. ‘Jacobs’ came to be related to Jacob’s ladder, an Old Testament allegory for the Christian’s ascent into heaven. It is linked in the list to ‘Rosenbaum’—rose tree in German and surely an allusion to the Virgin Mary, who is often depicted as a rose without thorns and promotes Christians’ ascent into heaven through the redemptive work of her son, Jesus. Redemption is effected above all through Christ’s suffering and death, symbolised in his being crowned with thorns (corrupted to ‘Thome’?). The reference to Levi (see ‘Levin’) is not surprising: the tribe of Levi was the priesdy tribe and Jesus, after all, is the Great High Priest of the New Testament. ‘Ohman’ could be given at least three readings (hence the question mark?): it might be ‘omen’ or ‘Oh Man!’ or simply ‘Amen’. The students also noted that both Old and New Testaments are represented in the poem, three of the names being Jewish, two Gentile, and one ambiguous. Perhaps this ambiguity is the reason for the question mark after it. And so on.

In the wake of this exercise, Fish asks the question that he uses to shape the tide of his essay: How do you recognise a poem when you see one? In this case, the students are not led to recognise the poem as a poem because of particular distinguishing features. The act of recognition comes first. They are told it is a poem. They are invited at the start to address the list on the board with ‘poetry-seeing eyes’. Having done that, they are able to detect particular significances in the object as a poem. Fish concludes that reading of any kind is along these same lines, that is, not ‘a matter of discerning what is there’ but ‘Of knowing how to produce what can thereafter be said to be there’ (1990, pp. 182- 3).

‘Just a moment! ’, some might want to argue. This list does have a meaning and the members of the first class did, in fact, discern ‘what is there’. The list is an assignment.

Fish remains unimpressed. ‘Unfortunately, the argument will not hold because the assignment we all see is no less the product of interpretation than the poem into which it was turned. That is, it requires just as much work, and work of the same kind, to see this as an assignment as it does to see it as a poem’ (Fish 1990, p. 184).

All right, then. It is not an assignment either. But it is a list of names.

We can read it as a list of names and that, surely, is to discern ‘what is there’. No, not even that, Fish assures us. ‘In order to see a list, one must already be equipped with the concepts of seriality, hierarchy, subordination, and so on’ (Fish 1990, p. 186). These have to be learned and one cannot see a list without learning them. The meaning of list, as of anything else, is not just ‘there’. Instead, making meaning is always an ‘ongoing accomplishment’. ‘The conclusion, therefore, is that all objects are made and not found and that they are made by the interpretive strategies we set in motion’ (Fish 1990, p. 191).

In Fish’s story we find human beings engaging with a reality and making sense of it. Obviously, it is possible to make sense of the same reality in quite different ways. Not that we need to be taught that lesson. Moving from one culture to another, as no doubt most of us have done at one time or another, provides evidence enough that strikingly diverse understandings can be formed of the same phenomenon. Yet there are always some who stand ready to dismiss other interpretations as merely quaint viewpoints that throw the ‘true’ or ‘valid’ interpretation into clearer relief. What constructionism drives home unambiguously is that there is no true or valid interpretation. There are useful interpretations, to be sure, and these stand over against interpretations that appear to serve no useful purpose. There are liberating forms of interpretation too; they contrast sharply with interpretations that prove oppressive. There are even interpretations that may be judged fulfilling and rewarding—in contradistinction to interpretations that impoverish human existence and stunt human growth. ‘Useful’, ‘liberating’, ‘fulfilling’, ‘rewarding’ interpretations, yes. ‘True’ or ‘valid’ interpretations, no.

There is another lesson that Fish’s example drives home, even if Fish does not make it explicit. It is something we have already noted. The object may be meaningless in itself but it has a vital part to play in the generation of meaning. While Fish’s students are innovative in making sense of the list of names conceived as a religious poem, the particular names that happen to be on the list play a key role. The students, Fish observes (1990, p. 184), ‘would have been able to turn any list of names into the kind of poem we have before us now’. What he does not point out, though he would surely agree, is that they would make different sense of a different list. With different names to engage with, the religious significances they develop would not be the same. It is therefore not a question of conjuring up a series of meanings and just imposing them on the ‘poem’. That is subjectivism, not constructionism. The meanings emerge from the students’ interaction with the ‘poem’ and relate to it essentially. The meanings are thus at once objective and subjective, their objectivity and subjectivity being indissolubly bound up with each other. Constructionism teaches us that meaning is always that.

No mere subjectivism here. Constructionism takes the object very seriously. It is open to the world. Theodor Adorno refers to the process involved as ‘exact fantasy’ (1977, p. 131). Imagination is required, to be sure. There is call for creativity. Yet we are not talking about imagination running wild or untrammelled creativity. There is an ‘exactness’ involved, for we are talking about imagination being exercised and creativity invoked in a precise interplay with something. Susan Buck- Morss (1977, p. 86) finds in Adorno’s exact fantasy ‘a dialectical concept which acknowledged the mutual mediation of subject and object without allowing either to get the upper hand’. It is, she insists, the attention to the object that ‘separated this fantasy from mere dream-like fabrication’.

Bringing objectivity and subjectivity together and holding them together throughout the process is hardly characteristic of qualitative research today. Instead, a rampant subjectivism seems to be abroad. It can be detected in the turning of phenomenology from a study of phenomena as the immediate objects of experience into a study of experiencing individuals. It is equally detectable in the move taking place in some quarters today to supplant ethnography with an ‘autoethnography’.

Description of researchers as bricoleurs is also a case in point. Denzin and Lincoln (1994) have made ‘researcher-as-bricoleur’ the leitmotif of the massive tome they have edited. They devote some columns to it in their opening chapter, refer to it in each of their introductions to the various sections of the book, and return to it in their concluding chapter. Denzin’s own chapter The art and politics of interpretation’ also invokes the notion of the researcher-as-bricoleur.

Denzin and Lincoln begin their treatment of the researcher-as- bricoleur by citing Levi-Strauss’s The Savage Mind. This is to the effect that the bricoleur is ‘a Jack of all trades, or a kind of professional do-it- yourself person’ (Denzin and Lincoln 1994, p. 2). Now the idea of a Jack (or Jill?) of all trades or a do-it-yourself person certainly puts the spodight on the multiple skills and resourcefulness of the individual concerned. This is precisely what Denzin and Lincoln seek to emphasise from start to finish. Bricoleurs, as these authors conceive them, show themselves very inventive in addressing particular tasks. The focus is on an individual’s ability to employ a large range of tools and methods, even unconventional ones, and therefore on his or her inventiveness, resourcefulness and imaginativeness. So the researcher-as-bricoleur ‘is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks’ and ‘is knowledgeable about the many interpretive paradigms (feminism, Marxism, cultural studies, constructivism) that can be brought to any particular problem’ (Denzin and Lincoln 1994, p. 2).

Given this understanding of bricoleur, it is not surprising that Denzin and Lincoln should characterise bricolage as ‘self-reflexive’, a description they draw from Nelson, Treichler and Grossberg (1992, p. 2) writing about cultural studies. When the Jacks and Jills of all trades learn that a job has to be done—they have just finished their carpentry around the door and have painted the ceiling, and now they learn that the toilet is blocked and requires some rather intricate plumbing work—yes, such bricoleurs would tend to be self-reflexive. ‘Can I do it?’ becomes the burning question.

Interestingly, the bricoleur described by Denzin and Lincoln is not the bricoleur described by Claude Levi-Strauss, even though he is the principal reference they give for the notion. The words they quote to describe the bricoleur, ‘a Jack of all trades, or a kind of professional do- it-yourself person’, come from a translator’s footnote (Levi-Strauss 1966, p. 17). In that footnote, the sentence cited is preceded by the statement, ‘The “bricoleur” has no precise equivalent in English’. And the sentence quoted is not given in full. The rest of the sentence reads: ‘but, as the text makes clear, he [the bricoleur] is of a different standing from, for instance, the English “odd job man” or handyman’.

What we find in Levi-Strauss’s text, in fact, is a very different understanding of bricoleur. Consequendy, the ‘analogy’ drawn from it (to use Levi-Strauss’s term) carries a very different message. In The Savage Mind, the bricoleur is not someone able to perform a whole range of specialist functions or even to employ unconventional methods. It is the notion of a person who makes something new out of a range of materials that had previously made up something different. The bricoleur is a makeshift artisan, armed with a collection of bits and pieces that were once standard parts of a certain whole but which the bricoleur, as bricoleur, now reconceives as parts of a new whole. Levi-Strauss provides an example. The bricoleur has a cube-shaped piece of oak. It may once have been part of a wardrobe. Or was it part of a grandfather clock? Whatever its earlier role, the bricoleur now has to make it serve a quite different purpose. It may be used as ‘a wedge to make up for the inadequate length of a plank of pine’ (Levi-Strauss 1966, p. 18). Or perhaps it ‘could be a pedestal—which would allow the grain and polish of the old wood to show to advantage’ (1966, pp. 18-19).

Engaged in that kind of project, bricoleurs are not at all ‘selfreflexive’. To the contrary, they are utterly focused on what they have to work with. The question is not, ‘Can I do it? Do I have the skills?’. Rather, the question is, ‘What can be made of these items? What do they lend themselves to becoming?’. And answering that depends on the qualities found in the items to hand. It is a matter of what items are there and what are not. It is a matter of the properties each possesses—size, shape, weight, colour, texture, britdeness, and so on. The last thing bricoleurs have in mind at this moment is their own self. Imaginativeness and creativity are required, to be sure, but an imaginativeness and creativity to be exercised in relation to these objects, these materials. An ice cream carton, two buttons, and a coat hanger— I’m supposed to make something of that? Self-reflexive? No, not at all. Nothing is further from self-reflexion than bricolage. There the focus is fairly and squarely on the object. True bricoleurs are people constandy musing over objects, engaged precisely with what is not themselves, in order to see what possibilities the objects have to offer. This is the image of the bricoleur to be found in Levi-Strauss.

Consider him at work and excited by his project. His first practical step is retrospective. He has to turn back to an already existent set made up of tools and materials, to consider or reconsider what it contains and, finally and above all, to engage in a sort of dialogue with it and, before choosing between them, to index the possible answers which the whole set can offer to his problem. He interrogates all the heterogeneous objects of which his treasury is composed to discover what each of them could ‘signify’ and so contribute to the definition of a set which has yet to materialize (Levi-Strauss 1966, p. 18)

A dialogue with the materials. Interrogating all the heterogeneous objects. Indexing their possible uses. This preoccupation with objects is mirrored in Levi-Strauss’s assertion that the bricoleur ‘might therefore be said to be constantly on the look out for “messages’” (1966, p. 20).

In their last page of text (1994, p. 584), Denzin and Lincoln come to acknowledge just a litde of all this. They state that ‘bricoleurs are more than simply jacks-of-all-trades; they are also inventors’. They write of bricoleurs having to ‘recycle used fabric’, to ‘cobble together stories’. Even here, however, the emphasis remains on the bricoleur’s inventiveness as ‘the demand of a resdess art’. In this further exposition of the bricoleur, there is still no hint of Levi-Strauss’s preoccupation with objects.

Why such preoccupation with objects? Because they are the limiting factor. They are, warns Levi-Strauss, ‘pre-constrained’. The possibilities they bear ‘always remain limited by the particular history of each piece and by those of its features which are already determined by the use for which it was originally intended or the modifications it has undergone for other purposes’ (Levi-Strauss 1966, p. 19). The uses to which they might be put must accord with what they are. The ability needed by the bricoleur is the ability to ‘re-vision’ these bits and pieces, casting aside the purposes which they once bore and for which they were once designed and divining very different purposes that they may now serve in new settings.

In short, the image of the researcher-as-bricoleur highlights the researcher’s need to pay sustained attention to the objects of research. This is much more to the fore than the need for versatility or resourcefulness in the use of tools and methods. Research in constructivist vein, research in the mode of the bricoleur, requires that we not remain straitjacketed by the conventional meanings we have been taught to associate with the object. Instead, such research invites us to approach the object in a radical spirit of openness to its potential for new or richer meaning. It is an invitation to reinterpretation.

It is precisely this preoccupation with the object that we find in Walter Benjamin and Theodor Adorno. In Benjamin’s form of inquiry, Adorno claims (1981, pp. 240-1), ‘the subjective intention is seen to be extinguished’ and the ‘thoughts press close to its object, seek to touch it, smell it, taste it and so thereby transform itself. Benjamin, in fact, is driven to ‘immerse himself without reserve in the world of multiplicity’. Adorno is the same:

What is ultimately most fascinating in Adorno’s Negative Dialectics is the incessantly formulated appeal that thought be conscious of its nonsovereignty, of the fact that it must always be molded by material that is by definition heterogeneous to it. This is what Adorno calls the ‘mimetic moment’ of knowledge, the affinity with the object What interests him most of all is to impose on thought respect for the nuance, the difference, individuation, requiring it to descend to the most minuscule and infinitesimal detail. (Tertulian 1985, p. 95)

A focus of this kind on the object is hardly characteristic of our times. ‘No age has been so self-conscious’, writes E.M. Cioran. What he calls our ‘psychological sense’ has ‘transformed us into spectators of ourselves’. He finds this reflected in the modem novel, wherein he finds ‘a research without points of references, an experiment pursued within an unfailing vacuity’. It does not look outwards to an object. ‘The genre, having squandered its substance, no longer has an object.’ (Cioran 1976, pp. 139-40).

To the narrative which suppresses what is narrated, an object, corresponds an askesis& of the intellect, a meditation without content. . . The mind discovers itself reduced to the action by virtue of which it is mind and nothing more. All its activities lead it back to itself, to that stationary development which keeps it from catching on to things. (Cioran 1976, p. 141)

Far removed from what Cioran is describing here, constmctionism does not suppress the object but focuses on it intently. It is by no means a stationary development. It is meditation with content. It well and truly catches on to things.

Constmctionism is not subjectivism. It is curiosity, not conceit.

Source: Michael J Crotty (1998), The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process, SAGE Publications Ltd; First edition.

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021

23 Jul 2021