There is always a need for replacement employees and those with unfamiliar skills that business growth makes necessary, and with the Institute for Employment Research (2006) now estimating that UK employers will be creating an additional 1.3 million jobs before 2014, it is clear that effective recruitment will remain a central HR objective for the foreseeable future. Recruitment is also an area in which there are important social and legal implications, but perhaps most important is the significant part played in the lives of individual men and women by their personal experience of recruitment and the failure to be recruited. Virtually everyone reading these pages will know how significant those experiences have been in their own lives.

Over three million people are recruited by employers in the UK each year. It can be a costly and difficult process when skills are in short supply and labour markets are tight. In such circumstances the employer needs to ‘sell’ its jobs to potential employees so as to ensure that it can generate an adequate pool of applicants, but even then for some groups of staff it is getting harder to find people who are both willing and able to fill the vacancies that are available. According to the CIPD annual survey of recruitment practice, the vast majority of respondents report experiencing recruitment difficulties, particularly when it comes to finding appropriate management and professional staff (CIPD 2006, pp. 6-7). This means that the time taken to fill vacancies is increasing as are the costs associated with recruitment. However, as Barber (1998) points out, it is important that employers do not consider the recruitment process to be finished at the point at which a pool of applications has been received. It continues during the shortlisting and interviewing stages and is only complete when an offer is made and accepted. Until that time there is an ongoing need to ensure that a favourable impression of the organisation as an employer is maintained in the minds of those whose services it wishes to secure. That said, it is also important to avoid overselling a job in a bid to secure the services of talented applicants. Making out that the experience of working in a role is going to be more interesting or exciting than it really will be is an easy trap to fall into, but ultimately it is counterproductive because it raises unrealistic expectations. These then

get quickly dashed, leading to unnecessary demotivation and, quite possibly, an early resignation. You will find further information and discussion exercises about realistic recruitment on our companion website www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

1. DETERMINING THE VACANCY

Is there a vacancy? Is it to be filled by a newly recruited employee? These are the first questions to be answered in recruitment. Potential vacancies occur either through someone leaving or as a result of expansion. When a person leaves, there is no more than a prima facie case for filling the vacancy thus caused. There may be other ways of filling the gap. Vacancies caused by expansion may be real or imagined. The desperately pressing need of an executive for an assistant may be a plea more for recognition than for assistance. The creation of a new post to deal with a specialist activity may be more appropriately handled by contracting that activity out to a supplier. Recruiting a new employee may be the most obvious tactic when a vacancy occurs, but it is not necessarily the most appropriate. Listed below are some of the options, several of which we discussed in Chapters 5 and 6:

- Reorganise the work

- Use overtime

- Mechanise the work

- Stagger the hours

- Make the job part time

- Subcontract the work

- Use an agency

If your decision is that you are going to recruit, there are four questions to determine the vacancy:

- What does the job consist of?

- In what way is it to be different from the job done by the previous incumbent?

- What are the aspects of the job that specify the type of candidate?

- What are the key aspects of the job that the ideal candidate wants to know before deciding to apply?

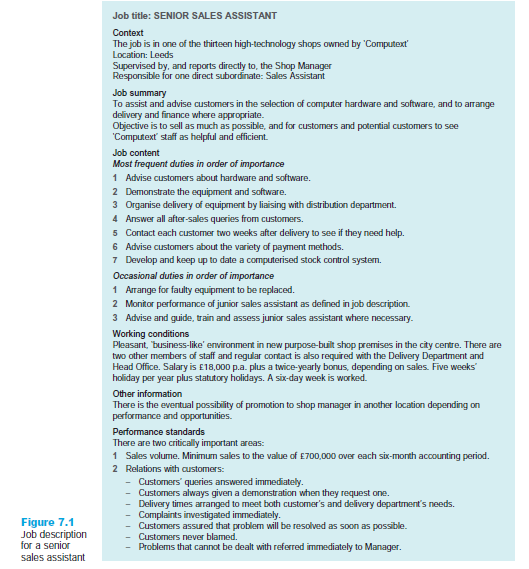

The conventional HR approach to these questions is to produce job descriptions and personnel specifications. Methods of doing this are well established. Good accounts are provided by Pearn and Kandola (1988), Brannick and Levine (2002) and IRS (2003a). The approach involves breaking the job down into its component parts, working out what its chief objectives will be and then recording this on paper. A person specification listing the key attributes required to undertake the role can then be derived from the job description and used in recruiting the new person. An example of a job description is given in Figure 7.1.

An alternative approach which allows for more flexibility is to dispense with the job description and to draw up a person specification using other criteria. One way of achieving this is to focus on the characteristics or competences of current job holders who are judged to be excellent performers. Instead of asking ‘What attributes are necessary to undertake this role?’ this second method involves asking ‘What attributes are shared by the people who have performed best in the role?’ According to some (for example Whiddett and Kandola 2000), the disadvantage of the latter approach is that it tends to produce employees who are very similar to one another and who address problems with the same basic mindset (corporate clones). Where innovation and creativity are wanted it helps to recruit people with more diverse characteristics.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!