When we surveyed the activities and priorities of HR specialists in the early 1980s, there was no doubt about the pre-eminence of employee relations as being the activity on which they spent most of their time and as being most central to the human resource function (Mackay and Torrington 1986, pp. 149, 161). Only in recruitment and selection did they feel that they had a slightly greater degree of discretion and scope in decision making (pp. 146-8). Twenty-five years on, the situation has wholly changed. Nowadays surveys of HR managers always show that employee relations issues are well down their lists of current and perceived future priorities (e.g. IRS 2006a, pp. 8-12). The emphasis is overwhelmingly on recruitment, staff retention, organisational restructuring, development and absence management, along with the HR implications associated with the introduction of new technologies and, in particular, legislation. The main reason appears to be a widespread perception that employee relations in UK organisations are in a healthy state. The 2004 Workplace Employment Relations (WER) Survey found that 93 per cent of HR managers believed their own organisations’ employment relations climate to be either ‘good’ or ‘very good’, while only one per cent saw it as being poor (Kersley et al. 2006, p. 277), suggesting that the pressures placed on many workforces to become more efficient and flexible are not in the main leading to overt forms of conflict. Employee relations is not therefore seen as an organisational problem. Interestingly the WER Survey also found that a majority of employees were positive about the employee relations climate in their own organisations, although theirs was a less enthusiastic endorsement (16 per cent characterised the climate as being ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’). Employee relations activities may not be as significant to HR practitioners as they once were, but they remain important. A poor employee relations climate can easily develop, while a good one is not created or maintained automatically; ongoing action on the part of managers is required.

1. KEY TRENDS IN EMPLOYEE RELATIONS

The past thirty years have witnessed a sea change in the UK employee relations scene. Most of the once well-established norms in British industry have been abandoned or have withered away as the nature of the work that we do and the types of workplace in which we are employed have evolved. To an extent, cultural change has accompanied this structural change too, creating a world of work in which employee attitudes towards their employers and employer attitudes towards their employees have developed in new directions. As we demonstrate throughout this book, ongoing change of one kind or another has affected and continues to affect most areas of HRM activity, but it is in the field of employee relations that the most profound transformations have occurred.

That said, it is important to appreciate that change in this field proceeds at a different pace in different places. There remain many workplaces, particularly in the public sector and in the former public sector corporations, in which more traditional models of employee relations continue to operate despite attempts by successive governments to change them. What we now have, therefore, is a far greater variety of approaches in place across the different industrial sectors than was the case in past decades.

1.1. Trade union decline

The most significant and fundamental trend is the decline in the number of people joining trade unions and taking part in trade union activity. In the UK membership levels reached a historic peak in 1979, when it was recorded that over 13 million people (58 per cent of all employees) were members of listed trade union organisations. In almost every year since then the number has declined as people have let their membership lapse, older members have retired and younger people have not replaced them. By 2005 membership among employees stood at just 6.4 million and represented just 26.2 per cent of the working population (DTI 2006, p. 1). The rate of decline has reduced somewhat in recent years, some unions reporting modest increases in their membership levels, but trade union density (i.e. the percentage of employees in membership) has fallen year on year for all but two of the past thirty years.

Because the decline started in 1979 at the time that Margaret Thatcher was first elected prime minister, the actions of her governments have frequently been cited as a major source of the trade unions’ decline. While it is true that a series of hostile employment Acts passed on to the statute books in the 1980s did not help the union cause, the extent to which these directly impacted on union decline was limited. The only full-frontal legal attack on the ability of unions to recruit members came in the form of regulations which made it impossible to sustain closed shop agreements whereby membership of a specific trade union was a necessary pre-condition of employment in certain workplaces. This was a major reform, affecting over five million employees who worked in closed shops (Dunn and Gennard 1984), but it did not lead directly to a great number of resignations from unions. Membership decline may have been partly precipitated by legislation of the 1980s and early 1990s which sought to reduce the number of strikes by making it harder for a union to press its demands through industrial action, but there is little evidence to support this. The view that ‘anti-union’ legislation can be blamed for membership decline in the UK is thus unconvincing, especially as the substantial downward trend in the number of trade unionists was and still is an international trend (see Vissa 2002).

The main cause of trade union decline has less to do with the employment policy of governments than with the kind of industrial restructuring that has occurred across the developed world. Established industries with union membership, such as mining, shipbuilding and heavy manufacturing, have declined. The jobs lost have been replaced by those in the service sector, in call centres, hospitality, tourism and retailing, where union membership is much rarer. The size of the average workplace has declined too, and this has reduced the propensity of employees to join a union. There are fewer large factories employing thousands on assembly and many more small-scale office and hi-tech manufacturing operations. Management styles in small workplaces, even when part of a much larger group, inevitably tend to be more ad hoc and personal. Grievances, disputes and requests for a pay rise are thus discussed and settled in face-to-face meetings or informally between people who know each other well, without the need to involve a trade union. Moreover, in the private services sector the proliferation of small workplaces means that alternative employment is readily available for suitably qualified people. When receptionists, shopworkers, sales executives, call-centre staff or IT people are dissatisfied with their work, their workplace or their managers, they can simply look for another job and resign. They do not need to move house to find work and are unlikely, in the present economic climate, to suffer any decline in income. Their jobs thus matter less to them than was the case in the days of the steel town, the mining village or the city suburb in which one big employer provided the lion’s share of all employment. In short, there is now less need to join a union because there are other ways of resolving problems at work and relieving discontent. Union members no longer enjoy the substantially higher wages and greater levels of job security that they used to, so the economic incentive for non-members to join is less strong too (Metcalf 2005).

By 2004 49 per cent of UK workplaces employing over 25 people stated that they employed no union members at all (Kersley et al. 2006, p. 110), while in tens of thousands more unions have no influence of any significance. For most employees, therefore, the norm is now to work in a non-union workplace. However, this is not true in the public sector, where union density remains high (64 per cent) and collective bargaining with full union recognition is still near universal. The same is true in the utility firms and in the transportation and education sectors. As a result, employee relations has come to be characterised by a far greater variety of forms than had been the case throughout much of the past century, traditional approaches continuing to decline:

What we find, therefore, is a marked split between the public sector, where traditional industrial relations appears to have survived, albeit with some adaptations, and a private sector which, with the exception of a declining set of large establishments, is predominantly non-union and without worker representation. . . . Management appears to be firmly in the driving seat, controlling the direction of employment relations. (Guest 2001, p. 99)

Whether continued trade union decline is inevitable produces diverse views. From a trade union perspective there are grounds for pessimism, despite years of new initiatives aimed at recruiting new members in the private sector. The proportion of younger people who choose to join unions has declined dramatically, suggesting that they do not see membership of a collective employee body as necessary or desirable. In 1991 as many as 37 per cent of people in the 25-34 age group were union members (Waddington 2003, p. 239). Ten years later, union density among the under 30s had fallen to just 16 per cent, compared with 34 per cent among those over the age of 30 (Freeman and Diamond 2003, p. 29). The second reason to anticipate further decline in the future relates to the continued growth of industries which have not traditionally been unionised. With the exception of some jobs in the public sector, the fastest-growing professions are all ones that have very low rates of union density (e.g. technicians, consultants, software engineers, nursery nurses, hairdressers and beauticians). These factors lead Metcalf (2005) to calculate that ‘long run union density will be around 20%, implying a rate of 12% in the private sector’.

The alternative view rests first of all on the observation that trade unions have been through periods of steep decline before and have later recovered. Kelly (1998) shows how union membership declined steeply during the 1920s and early 1930s, density falling as low as 22 per cent in 1933, only to recover again afterwards. His theory of ‘long waves’ in industrial relations leads him to conclude that workers will only ever put up with so much ‘exploitation and domination’ by employers, before beginning to unite to fight back. Others take heart from research which shows that many employees in the non-union sectors (including young people) are neither strongly opposed to unions, nor unwilling to countenance joining a union in the future. Fifty per cent of those asked in a poll in 2001 said that they would be either ‘very likely’ or ‘fairly likely’ to join if one were available at their workplace (Charlwood 2003, p. 52), while positive attitudes to unions appear to be just as common among non-members as they are among members (Prowse and Prowse 2006). These figures suggest that unions could create a renaissance for themselves if they could find more effective ways of organising and marketing themselves in the private services sector. You will find an article and some discussion exercises focusing on the prospects for trade union revival on our companion website, www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

1.2. Collective bargaining and industrial action

A major consequence of the decline in trade union membership has been a simultaneous decline in the number of employees whose terms and conditions are determined through collective bargaining (i.e. negotiation with a union or unions). Here, too, dramatic changes have occurred over recent decades. We have moved from a position in which a large majority of people worked in establishments which recognised trade unions, to one in which a large majority do not. In 1970 over 80 per cent of the UK workforce was covered by collective agreements. Thirty-five years later, the figure was just 35.3 per cent (DTI 2006, p. 12).

Profound changes have also occurred within the sectors that remain covered by collective agreements, and continue to do so. Over several decades we have seen the breaking down of the system of national collective bargaining established in the middle years of the twentieth century. Agreements of this kind are now very rare outside the public sector whereas once they were the norm. They involve terms and conditions being agreed at industry level between representatives of the relevant unions and an employers association, resulting in an agreement to which all operating in the industry agree to adhere. One by one arrangements of this kind have collapsed as collective bargaining, where it continues at all, increasingly takes place at the level of the organisation or the individual workplace. In 1960, according to Brown et al. (2003), 60 per cent of UK employees were covered by industry-level collective agreements. By 1980 the proportion had fallen to 43 per cent and by 2004 to only seven per cent. These remaining agreements are largely in the public sector and are themselves under robust attack from government ministers who see local bargaining as a more efficient and fairer way of distributing public money.

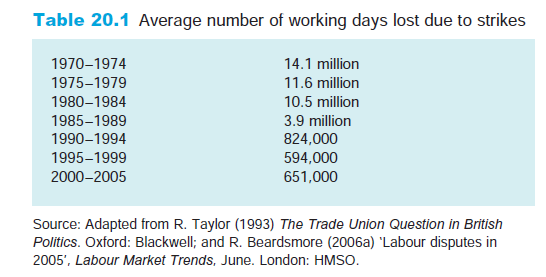

Another significant change in employee relations has been the very marked decline in the incidence of industrial action in recent years. Contrary to commonly held perceptions, UK workers have never been more prone to take industrial action than their counterparts in other countries, but the 1970s and early 1980s did see the loss of millions of days’ work as a result of strikes, not to mention the fall of at least two governments in the wake of major disputes. The position is now wholly transformed. The UK’s strike rate has been below the average for both the European Union and the OECD countries in every year except one since 1992 (Beardsmore 2006b), while the subject has long ceased to be one which influences voting patterns. The number of stoppages varies from year to year. In 2002, for example, there was a marked increase due to a long-running dispute in the fire service, but the overall trend has been downwards for over a decade. The number of working days lost to strikes each year is now a fraction of what it was thirty years ago (see Table 20.1). Some argue that we can expect to see an increase in the incidence of industrial action over coming years in the public sector as employees respond to government attempts to restructure services and reduce the costs associated with providing generous occupational pensions. Industrial action in the private sector, by contrast, is generally expected to remain rare and restricted to specific sectors (IRS 2006b).

1.3. The rise of employment law

Until the 1960s there was no such thing as employment law in Britain. With the exception of basic protection for child workers and some health and safety regulations, the state ‘kept its distance’ from the relationship between employers and employees. This became known as the principle of voluntarism and it meant that the UK differed very markedly from most other industrialised countries. All workers and employers, it was argued, were free to enter into whatever contractual relationship they preferred and it was not for the state to determine people’s terms and conditions or to set minimum standards. All the courts did was provide a mechanism for contracts of employment to be enforced when one side or the other breached them or sought to change them unilaterally without the consent of the other party. Protection from injustices perpetrated by managers and abuse of power was provided by trade unions and through collective agreements.

Over the past forty years this position has wholly reversed. In 1965 the first major piece of modern employment legislation was introduced – a right for redundant workers to receive payments by way of compensation. In the years since a major new field of legal practice has been created as the law has intervened more and more in the regulation of the employment relationship. As trade unions have declined in size and influence, the law has stepped in to provide a minimum floor of rights and to deter employers from acting without proper employee relations procedures. In recent years many developments have originated at European level, but UK governments have pushed the agenda forward on their own account too.

Unfair dismissal law dates from 1971, sex discrimination law from 1975 and race discrimination law from 1976. Since 1974 we have had comprehensive health and safety law together with a government inspectorate to enforce it. Regulations relating to ‘transfers of undertakings’ were introduced in 1981, when it also became a formal requirement to consult collectively when making redundancies. The past ten years have seen an astonishing quickening of the pace. We now have disability discrimination law, a national minimum wage, restrictions on working time, compulsory union recognition, a host of new family-friendly measures, extensive data protection law and measures preventing discrimination against people employed on fixed-term and part-time contracts. In 2003 new regulations outlawing discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and religion or belief were introduced, and there were significant improvements to the rights of people with family responsibilities. In 2004 new workplace dispute resolution measures came into force and in 2005 significant new obligations were introduced in the field of information and consultation. Age discrimination legislation was introduced in 2006 and 2007 saw a major extentsion of maternity and other family-friendly rights.

Employment tribunals now oversee nearly one hundred separate areas of jurisdiction (i.e. distinct types of claim that an aggrieved employee, ex-employee or job applicant can bring before them). In addition there are some thirty or forty separate types of claim rooted in the laws of contract, trust or tort that can be taken to the county courts. Around 100,000 claims are lodged with the Employment Tribunal Service each year, leading the government to reform procedures and adjust remedies so as to discourage parties from pursuing cases they are unlikely to win.

Given the acceleration of developments in the field of employment law, it is not surprising that its implementation by organisations now comes so much higher up HR managers’ agendas than more traditional employee relations concerns (IRS 2006a). Two- thirds of HR specialists claim to spend in excess of 20 per cent of their time ‘dealing with employment law issues’, while a quarter report that over 40 per cent of their working days are spent in this way (CIPD 2002). In the vast majority of workplaces the nature of the relationship that is established between employers and employees, and the rules that govern it, owe far more to the requirements of employment law than to the demands of trade unions. This represents a total transformation from the position that prevailed a generation ago.

2. STRATEGIC CHOICES

Most organisations in the UK do not have a clearly identifiable employee relations strategy which their managers can readily articulate. At no point have managers at senior levels determined what the general approach or philosophy of the organisation should be towards the relationship it has with its employees, either individually or collectively. While it may be possible to identify the operation of a clear management style or the presence of definable employee relations culture, these have not in most cases been shaped in a deliberate or coherent manner by managers (Blyton and Turnball 2004: 121). Instead, pragmatism reigns and employee relations issues only receive serious attention at senior levels when problems arise (Keenoy 1992, p. 97).

The reason for this is that there is often only limited scope for individual managers or teams of managers, however senior, to determine the nature of the employment relationships in an organisation. Whereas a reward strategy or an employee development strategy can be thought through, devised and then introduced by managers with relative ease, altering, let alone shaping the direction of employee relations is far harder to achieve. This is because the nature of the employment relationship in an organisation is controlled to a considerable extent by the attitudes, outlook and responses of employees. While managers can often readily get employees to do what they want them to, they cannot do more than influence their hearts and minds. As a result, even if a strategic approach to employee relations is developed, there is no guarantee that it will be successfully implemented and the extent of its success will always be difficult to measure objectively and accurately.

Moreover, the defining characteristics of the employment relationship in most organisations are heavily determined by the nature of the work that is being carried out and the way that it is organised. For example, a new manufacturing plant which mass produces goods via assembly lines is inevitably going to develop different kinds of employment relationships with its staff than would be the case in a new shop, hotel, hospital or government department. Different types of workplace develop clearly differentiated cultures derived from the complexity of work that they carry out, the nature of customer interactions, the extent of competition and the nature of the skills and qualifications their staff possess. Once established, workplace cultures are difficult to change, and this means that the nature of established employment relationships is difficult to change too.

Despite these difficulties, it can be strongly argued that organisations are more effective when their senior managers do think strategically about the employment relationship and develop policies and practices which help them to achieve clearly articulated objectives. There are strategic choices to be made in the field of employee relations and it is better that these should be considered and rational, rather than determined in an ad hoc, inconsistent and reactive fashion.

2.1. Management control

It would be a great deal easier for organisations if their employees had an innate desire to come to work on time every day and carry out their duties in a highly efficient fashion and were always happy to accept change. If this were the case there would hardly be a need to employ managers at all, while terms such as ‘industrial conflict’ would never have been invented. But, of course, the real world is very different. Employees and their employers share some interests in common, but what they aim to get from their relationship also varies considerably. There is thus an ever-present need, from a management perspective, to supervise what employees are doing and, more generally, to exercise a degree of control over a workplace. However, the nature of the control that is exercised varies from organisation to organisation, and this is largely a matter determined by management.

The central choice is between the two fundamentally different control strategies identified by Friedman (1977); ‘direct control’ and ‘responsible autonomy’. The former involves close supervision by managers who determine what work is done, when and by whom. Employees are required to do what they are told and are not given any meaningful day-to-day influence over the way their work is organised or performed. Hard work is rewarded, while disciplinary sanctions are conspicuously used to deter recalcitrant behaviour. This is a model of control that is often seen as being similar to that used in the armed forces, although its origins lie as much in the the ideas of F.W. Taylor (see Chapter 1) and the school of scientific management which sought to organise work in the way that an engineer might design a machine. Responsible autonomy, by contrast, is both subtler and a great deal more pleasant from the employees’ point of view. It is also believed by many managers to be more desirable because it leads to less conflict with staff, and more cost effective because less management time needs to be spent supervising the activities of others. Here the organisation sets the objectives, communicating clearly to its staff what it wants them to achieve, but it allows employees as much autonomy as is practicable to decide how and when they meet these objectives.

2.2. Labour-market orientation

In Chapter 5 we looked in detail at the strategic choices available to organisations when interacting with their labour markets. We noted that in recent years most labour markets have tightened, making it harder for employers to recruit and retain good performers. Staff who are unhappy now have more alternative employment opportunities open to them and can thus either switch employers, or credibly threaten to do so if they find that their objectives from an employment relationship are not being met. For an employer seeking to respond effectively employee relations practices have a great deal to contribute because of the major role they play in influencing job satisfaction.

One strategic choice that many employers have taken in response to tightening labour market conditions has been to seek status as an ‘employer of choice’ or even as the employer of choice in their industry. This involves making themselves more attractive to prospective employees than competitor organisations, the aim being to secure and then to hold on to the services of high performers. Positioning an organisation as an employer of choice can be expensive in the short term, but over time dividends are reaped because fewer people are required, and those that are employed help ensure that the organisation meets its objectives more effectively and efficiently than its rivals. Sustained competitive advantage thus results. It follows that employers seeking to achieve employer of choice status, or simply aiming to recruit and retain more effectively, need to develop employee relations strategies that increase the chances that employees are satisfied and decrease the likelihood of dissatisfaction.

Taylor (2001, p. 15) drawing on the work of Michael White and Stephen Hill states that contemporary research into what employees want to achieve from the employment relationship consistently reports a desire, above other possibilities, for the following:

- an interesting job

- employment security

- a feeling of positive accomplishment

- influence over how their job gets done

This strongly suggests that there are substantial long-term dividends to be gained by employers who develop sophisticated employee relations strategies. Effective employee involvement practices are central as are approaches to supervision which combine responsible autonomy with strong positive feedback mechanisms. Involving employees in the management of change is particularly important so as to minimise perceptions of insecurity. Above all an employer of choice requires an employee relations strategy which is built around a view of employees as individuals with different personalities, attributes and ambitions. A traditional approach which views employees as a mass group of people with identical aspirations is unlikely to deliver jobs which individuals find interesting or fulfilling.

Not all labour markets are tight, and while they have tightened considerably over the long term in most parts of the UK, it is important to recognise that there are areas of high unemployment both in this country and overseas. Moreover, in all countries, there are groups of people who lack sufficient basic skills or whose skills have become obsolete. In such conditions employers are not required to become employers of choice in order to recruit and retain effective staff. People may prefer jobs which are interesting, secure and satisfying, and may desire a degree of influence over how they do their jobs, but management do not have to provide such employment for reasons of commercial necessity. Where competitive pressures require organisations to minimise costs in order to survive and prosper, a rather different employee relations strategy is appropriate. Policies are likely to be highly standardised, employee involvement limited and few formal opportunities for positive feedback provided. Jobs are designed first and foremost around the need of the organisation to maximise its efficiency rather than the needs or aspirations of employees. In such conditions employers are often tempted to avoid legal obligations, taking short cuts with health and safety for example, and may permit managers at the local level to take a somewhat ‘flexible’ approach when interpreting written policy.

In between these two extreme types of employee relations strategy there are a variety of other possibilities. Shore et al. (2004), for example, refer to employee relations strategies adopted by US companies which differentiate between ‘core’ and ‘non-core’ employees, the purpose of which is to ensure that the former are retained while maximum efficiency is extracted from the latter. They also describe employee relations strategies which vary from division to division within a corporation depending on the particular business strategy being pursued.

2.3. Management style

So far we have only discussed strategic choices in employee relations as they affect the individual employment relationship. Debates about what is usually termed ‘management style’ relate to the different approaches employers choose to take as far as the collective employment relationship is concerned. How does an employer wish to view its relationship with its employees as a group? Does it wish to engage with them through representatives whom they appoint or elect? Does it wish to establish formal mechanisms for consultation or negotiation? What is its approach to possible trade union recognition?

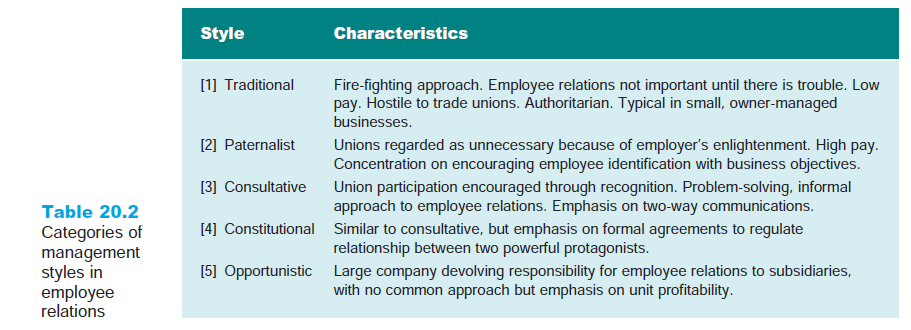

One of the best-known typologies of management style is that developed by Purcell and Sisson (1983) following extensive research into the different approaches favoured by employers. These are summarised in Table 20.2. Their categories are useful, although some organisations do not fit easily into any one of them. Most large, long-established companies will be in one of the last three; most public sector organisations will be in category 4; and many newer businesses will be in some version of category 2. Smaller organisations tend to take the ‘traditional’ approach, having no considered employee relations strategy in place.

It is also possible to view management styles in terms of the extent and nature of collective employee participation in decision making. Below we set out seven categories of consent, in which there is a steadily increasing degree of involvement. We begin with a category in which there is straightforward and unquestioning acceptance of management authority, and then move through various stages of increasing participation in decision making and the necessary changes in management style as the power balance alters and the significance of bargaining develops and extends to more and more areas of organisational life.

- Normative. We use this term in the sense of Etzioni (1961), who described ‘normative’ organisations as those in which the involvement of individuals was attributable to a strong sense of moral obligation. Any challenge to authority would imply a refutation of the shared norms and was therefore unthinkable. Many of the exercises in corporate culture are construed by some as strategies to develop this type of consent, with strong emphasis on commitment and the suppression of views opposed to managerial orthodoxy.

- Disorganised. In organisations that are not normative there may be collective consent simply because there is no collective focus for a challenge; disorganised consent is where there may be discontent but consent is maintained through lack of employee organisation to articulate and endorse the dissatisfaction. A Victorian sweatshop would come into this category.

- Organised. When employees organise it is nearly always in trade unions and the first collective activities are usually those dealing with general grievances. It is very unlikely that there will be any degree of involvement in the management decisionmaking processes. Employees simply consent to obey instructions as long as grievances are dealt with.

- Consultative. Consultation is a stage of development beyond initial trade union recognition, even though some employers consult with employees before – often as a means of deferring – trade union recognition. This is the first incursion into the management process as employees are asked for an opinion about management proposals before decisions are made, even though the right to decide remains with the management.

- Negotiated. Negotiation implies that both parties have the power to commit and the power to withhold agreement, so that a decision can only be reached by some form of mutual accommodation. No longer is the management retaining all decision making for itself; it is seeking some sort of bargain with employee representatives, recognising that only such reciprocity can produce what is needed.

- Participative. When employee representatives reach the stage of participating in the general management of the business in which they are employed, there is a fundamental change in the control of that business, even though this may initially be theoretical rather than actual. Employee representatives take part in making the decisions on major strategic issues such as expenditure on research, the opening of new plants and the introduction of new products. In arrangements for participative consent there is a balance between the decision makers representing the interests of capital and those representing the interests of labour, though the balance is not necessarily even.

- Controlling. If the employees acquire control of the organisation, as in a workers’ cooperative, then the consent is a controlling type. This may sound bizarre, but there will still be a management apparatus within the organisation to which employee collective consent will be given or from which it will be withheld.

All of the above categories require some management initiative to sustain collective consent. In categories 1 and 2 it may be exhortation to ensure that commitment is kept up, or information supplied to defer organisation. In each subsequent category there is an increasing bargaining emphasis, which becomes progressively more complex. The implication is that there is a hierarchy of consent categories, through which organisations steadily progress. Although this has frequently been true in the past, it is by no means necessary.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

Hi my family member! I wish to say that this article is awesome, nice written and come with almost all important infos. I?¦d like to see extra posts like this .