1. PART-TIME WORKERS

Discriminating against a female part-time worker has long been taken by the courts to constitute indirect sex discrimination because the vast majority of part-time workers are female. Since 2000, however, it has not been necessary for part-time workers (of either gender) to use sex discrimination law to protect themselves. The Part-time Workers (Prevention of Less Favourable Treatment) Regulations 2000 were introduced to ensure that the UK complied with the EU’s Part-Time Workers Directive. They now seek to ensure that part-time workers (not just employees) are treated equally with full-time workers in all aspects of work, the key features being as follows:

- Part-time workers who believe that they are being treated less favourably than a comparable full-time colleague can write to their employer asking for an explanation.

- This must be given in writing within 14 days.

- Where the explanation given by the employer is considered unsatisfactory, the parttime worker may ask an employment tribunal to require the employer to affirm the right to equal treatment.

- Employers are required under the regulations to review their terms and conditions and to give part-timers pro rata rights with those of comparable full-timers.

- There is a right not to be victimised on account of enforcing rights under the Parttime Workers Regulations.

- Any term or condition of employment is covered by the regulations, as is any detriment caused as a result of failure to be promoted or given access to training. It is also now unlawful to select someone for redundancy simply because he or she works part-time.

There are a number of problems with the new regulations, including the absence of a statutory authority to enforce the third of the above points. One of the more complex issues involves how the term ‘part-time worker’ should be defined, because it is used differently in different workplaces. In some organisations someone working 35 hours a week is employed on a ‘part-time contract’ because full-time hours are 40 per week. Elsewhere, where everyone works 35 hours, such a worker would be regarded as a full-timer. The regulations simply state that a worker is part-time if he or she works fewer hours in a week than are worked by recognised full-timers. This obviously poses difficulties for organisations which do not employ people to work a set number of hours a week, or for whom patterns of hours vary considerably over the course of a year. There is also a need for part-time workers who consider themselves to have been less favourably treated to name a comparator employed in a broadly similar job who is employed on a full-time basis in the same employment. Where none exists it is effectively impossible to bring a claim.

2. FIXED-TERM WORKERS

The EU’s Fixed-term Work Directive (brought into UK law via the Employment Act 2000) includes a range of important provisions designed to improve the position of the many employees who are employed on temporary contracts. The general requirement is that a fixed-term employee should not be treated less favourably than a comparable permanent employee unless less favourable treatment can be objectively justified. This has meant an end to the common practice of avoiding making redundancy payments when fixed-term contracts finish by including a waiver clause in the contract of employment. The statute extends to fixed-term employees the right to receive statutory sick pay (SSP) in the same way as permanent staff and also requires employers to inform fixed-term employees about permanent vacancies in the organisation.

However, the most significant change is the restriction on the employment of people on successive fixed-term contracts. In the past employers commonly used this device to give themselves numerical flexibility and, many would argue, to extract greater effort out of people who were in constant fear of the consequences of non-renewal. Employment of people on successive fixed-term contracts is now limited to four years unless further extensions can be objectively justified. It thus remains acceptable to extend a fixed-term contract beyond four years if the money to fund the post is limited or if a specific project is clearly coming to an end within a short period of time. However, in other situations, after four years the law treats all fixed-term contracts as if they were permanent.

The law gives fixed-term employees the right to ask for a written statement of reasons from their employer if they are being treated unfavourably as well as a statement that their contract has become permanent after four years. Where employers fail to honour these rights or to give satisfactory explanations, complaints can be taken to an employment tribunal.

3. EX-OFFENDERS

Another group who are given some measure of legal protection from discrimination at work are ex-offenders whose convictions have been ‘spent’. The relevant legislation is contained in the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 which sets out after how many

years different types of criminal conviction become spent and need not be acknowledged by the perpetrator. In the field of employment, protection from discrimination extends to dismissal, exclusion from a position and ‘prejudicing’ someone in any way in their employment. In other words, employers cannot dismiss people, fail to recruit them or hold them back in their occupations simply because they are known or discovered to have a former conviction. Failing to disclose the conviction can also be no grounds for discrimination. Moreover, no one (the individual concerned or anyone else) is under any obligation to tell anyone else about the conviction once it has been spent. Effectively, the slate is wiped clean, allowing the ex-offender to live and work as if no conviction had been received.

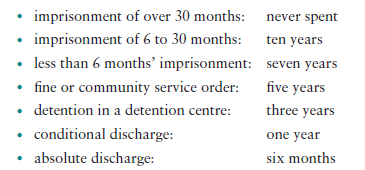

The rehabilitation periods set out in the Act vary depending on the type of sentence that has been received. The tariff is as follows:

The time runs from the date of the conviction, the times being cut in half for those who are under the age of 18 at this time. It is the sentence imposed that is relevant to the Act and not the sentence actually served.

Numerous jobs and occupations are excluded from the terms of the Act. Organisations which employ people to work in these positions are entitled to know about spent convictions and can lawfully discriminate against individuals on these grounds. The list includes all jobs which involve the provision of services to minors, employment in the social services, nursing homes and courts, as well as employment in the legal, medical and accountancy professions.

At the time of writing the government is proposing to make a series of relatively minor amendments to the law on the rehabilitation of offenders, but no date has been given for their introduction.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I am continuously searching online for tips that can assist me. Thank you!

I went over this website and I believe you have a lot of wonderful info , saved to my bookmarks (:.