The Project Portfolio Process (PPP) attempts to link the organization’s projects directly to the goals and strategy of the organization. This occurs not only in the project’s initiation and planning phases, but also throughout the life cycle of the projects as they are managed and eventually brought to completion. This topic is compared to project and program management in PMBOK’s Chapter 1: Introduction. Thus, the PPP is also a means for monitoring and controlling the organization’s strategic projects, as will be reiterated in Chapter 7: Monitoring and Controlling the Project. On occasion this will mean shutting down projects prior to their completion because their risks have become excessive, their costs have escalated beyond their expected benefits, another (or a new) project does a better job of supporting the goals, or any of a variety of similar reasons. The steps in this process generally follow those described in Longman, Sandahl, and Speir (1999) and Englund and Graham (1999).

The first step is to appoint a Project Council to establish and articulate a strategic direction for projects. The Council should report to a senior executive since it will be responsible for allocating funds to those projects that support the organization’s goals and controlling the allocation of resources and skills to the projects. In addition to senior management, other appropriate members of the Project Council include program managers, project managers of major projects; the head of the PMO, and general managers who can identify key opportunities and risks facing the organization.

Next, various project categories are identified so the mix of projects funded by the organization will be spread appropriately across those areas making major contributions to the organization’s goals. In addition, within each category criteria are established to discriminate between very good and even better projects using the weighted scoring model previously discussed. The criteria are also weighted to reflect their relative importance.

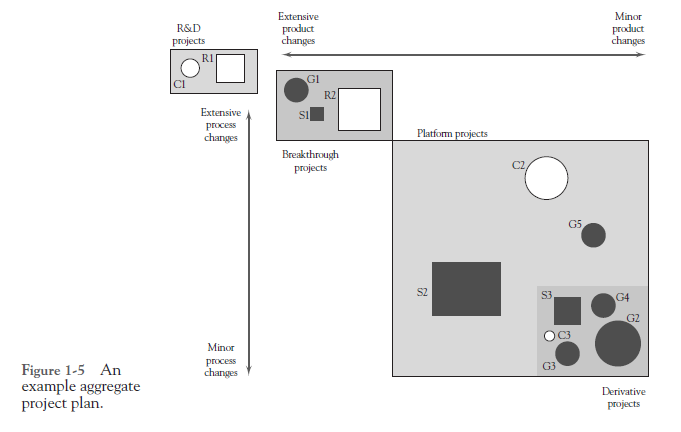

The first task in this step is to list the goals of each existing and proposed project— that is, the mission, or purpose, of each project. Relating these to the organization’s goals and strategies should allow the Council to identify a variety of categories that are important to achieving the organization’s goals. One way to position many of the projects (particularly product/service development projects) is in terms of the extent of product and process changes. Wheelwright and Clark (1992) have developed a matrix called the aggregate project plan illustrating these changes, as shown in Figure 1-5. Based on the extent of product change and process change, they identified four separate categories of projects:

- Derivative projects These are projects with objectives or deliverables that are only incrementally different in both product and process from existing offerings. They are often meant to replace current offerings or add an extension to current offerings (lower priced version, upscale version).

- Platform projects The planned outputs of these projects represent major departures from existing offerings in terms of either the product/service itself or the process used to make and deliver it, or both. As such, they become “platforms” for the next generation of organizational offerings, such as a new model of automobile or a new type of insurance plan. They form the basis for follow-on derivative projects that attempt to extend the platform in various dimensions.

- Breakthrough projects Breakthrough projects typically involve a newer technology than platform projects. It may be a “disruptive” technology that is known to the industry or something proprietary that the organization has been developing over time. Examples here include the use of fiber-optic cables for data transmission, cash- balance pension plans, and hybrid gasoline-electric automobiles.

- R&D projects These projects are “blue-sky,” visionary endeavors, oriented toward using newly developed technologies, or existing technologies in a new manner. They may also be for acquiring new knowledge, or developing new technologies themselves.

The size of the projects plotted on the array indicates the size/resource needs of the project, and the shape may indicate another aspect of the project (e.g., internal/external, long/medium/short term, or whatever aspect needs to be shown). The numbers indicate the order, or time frame, in which the projects are to be (or were) implemented, separated by category, if desired.

The aggregate project plan can be used to:

- View the mix of projects within each illustrated aspect (shape)

- Analyze and adjust the mix of projects within each category or aspect

- Assess the resource demands on the organization, indicated by the size, timing, and number of projects shown

- Identify and adjust the gaps in the categories, aspects, sizes, and timing of the projects

- Identify potential career paths for developing project managers, such as team members of a derivative project, then team member of a platform project, manager of a derivative project, member of a breakthrough project, and so on

For each existing and proposed project, assemble the data appropriate to that category’s criteria. Include the timing, both date and duration, for expected benefits and resource needs. Use the project plan, a schedule of project activities, past experience, expert opinion, whatever is available to get a good estimate of these data. If the project is new, you may want to fund only enough work on the project to verify the assumptions.

Next, use the criteria score limits, or constraints as described in our discussions of scoring models, to screen out the weaker projects. For example, have costs on existing projects escalated beyond the project’s expected benefits? Has the benefit of a project lessened because the organization’s goals have changed? Also, screen in any projects that do not require deliberation, such as projects mandated by regulations or laws, projects that are competitive or operating necessities (described above), projects required for environmental or personnel reasons, and so on. The fewer projects that need to be compared and analyzed, the easier the work of the Council.

When we discussed financial models and scoring models, we urged the use of multiple criteria when selecting projects. ROI on a project may be lower than the firm’s cut-off rate, or even negative, but the project may be a platform for follow-on projects that have very high benefits for the firm. Wheatly (2009) also warns against the use of a single criterion, commonly the return on investment (ROI), to evaluate projects. A project aimed at boosting employee satisfaction will often yield improvements in output, quality, costs, and other such factors. For example, Mindtree, of Bangalore, India, measures benefits on five dimensions; revenue, profit, customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and intellectual capital created—in sum, “Have we become a better company?”

Next, assess the availability of both internal and external resources, by type, department, and timing. Timing is particularly important, since project resource needs by type typically vary up to 100 percent over the life cycle of projects. Needing a normally plentiful resource at the same moment it is fully utilized elsewhere may doom an otherwise promising project. Eventually, the Council will be trying to balance aggregate project resource needs over future periods with resource availabilities, so timing is as important as the amount of maximum demand and availability. Many managers insist on trying to schedule resource usage as closely as possible to system capacity. This is almost certain to produce a catastrophe (see Section 6.3, subsection on Resource Loading/Leveling and Uncertainty).

Then use multiple screens to reduce the number of competing projects. The first screen should be each project’s support of the organization’s goals, but other possible screens might be:

- Whether the required competence exists in the organization

- Whether there is a market for the offering

- The likely profitability of the offering

- How risky the project is

- If there is a potential partner to help with the project

- If the right resources are available at the right times

- If the project uses the organization’s strengths, or depends on its weaknesses

- If the project is synergistic with other important projects

- If the project is dominated by another existing or proposed project

- If the project has slipped in its desirability since the last evaluation

Now apply the scores and criterion weights to rank the projects within each category. It is acceptable to hold some hard-to-measure criteria out for subjective evaluation, such as riskiness, or development of new knowledge. Subjective evaluations can be translated from verbal to numeric terms easily by the Delphi * Method, pairwise comparisons, or other methods.

Finally, select the projects to be funded and those to be held in reserve. That is, determine the mix of projects across the various categories and time periods. Next be sure to leave some percentage (e.g., 20%) of the organization’s resource capacity free for new opportunities, crises in existing projects, errors in estimates, and so on. Then allocate the categorized projects in rank order to the categories according to the mix desired. It is usually good practice to include some speculative projects in each category to allow future options, knowledge improvement, additional experience in new areas, and so on. The focus should be on committing to fewer projects but with sufficient funding to allow project completion. Document why late projects were delayed and why any were defended.

Be sure to make the results of the PPP widely known, including the documented reasons for project cancellations, deferrals, and nonselection as was mentioned earlier. Top management must now make their commitment to this project portfolio process totally clear by supporting the process and its results. This may require a PPP champion near the top of the organization. As project proposers come to understand and appreciate the workings and importance of the PPP, their proposals will more closely fit the profile of the kinds of projects the organization wishes to fund. As this happens, it is important to note that the Council will have to concern itself with the reliability and accuracy of proposals competing for limited funds. Senior management must fully fund the selected projects. It is unethical and inappropriate for senior management to undermine PPP and the Council as well as strategically important projects by playing a game of arbitrarily cutting x percent from project budgets. It is equally unethical and inappropriate to pad potential project budgets on the expectation that they will be arbitrarily cut.

Finally, the process must be repeated on a regular basis. The Council should determine the frequency, which to some extent will depend on the speed of change within the organization’s industry. For some industries, quarterly analysis may be best, while in slow- moving industries yearly may be fine.

In an article on competitive intelligence, Gale (2008b) reports that Cisco Systems Inc. constantly tracks industry trends, competitors, the stock market, and end users to stay ahead of their competition and to know which potential projects to fund. Pharmaceutical companies are equally interested in knowing which projects to drop if competitors are too far ahead of them, thereby saving millions of dollars in development and testing costs.

When reading a text, it is helpful to understand how the book is organized and where it will take the reader. Following this introductory chapter, our attention goes to the various roles the PM must play and the ways projects are organized. Chapter 2 focuses on the behavioral and structural aspects of projects and their management. It describes the PM’s roles as communicator, negotiator, and manager. It also includes a discussion of project management as a profession and reports briefly on the Project Management Institute (PMI), the PM’s professional organization. Then attention turns to the ways in which

Source: Meredith Jack R., Mantel Jr. Samuel J., Shafer Scott M., Sutton Margaret M. (2017), Project Management in Practice, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 3th Edition.

It’s an awesome post for all the internet visitors; they will obtain benefit from

it I am sure.

I have learn some just right stuff here. Certainly value bookmarking for

revisiting. I surprise how a lot attempt you put to make this kind of great informative website.

Hello, I enjoy reading through your article. I like to write a

little comment to support you.

Very soon this site will be famous among all blogging visitors, due to it’s pleasant articles or reviews