Three theoretical approaches to strategic HRM can be identified. The first is founded on the concept that there is ‘one best way’ of managing human resources in order to improve business performance. The second focuses on the need to align employment policies and practice with the requirements of business strategy in order that the latter will be achieved and the business will be successful. This second approach is based on the assumption that different types of HR strategies will be suitable for different types of business strategies. Third, a more recent approach to strategic HRM is derived from the resource-based view of the firm, and the perceived value of human capital. This view focuses on the quality of the human resources available to the organisation and their ability to learn and adapt more quickly than their competitors. Supporters of this perspective challenge the need to secure a mechanistic fit with business strategy and focus instead on long-term sustainability and survival of the organisation via the pool of human capital.

1. Universalist approach

The perspective of the universalist approach is derived from the conception of human resource management as ‘best practice’, as we discussed in Chapter 1. In other words it is based on the premise that one model of labour management – a high-commitment model – is related to high organisational performance in all contexts, irrespective of the particular competitive strategy of the organisation. An expression of this approach can be seen in Guest’s theory of HRM, which is a prescriptive model based on four HR policy goals: strategic integration, commitment, flexibility and quality. These policy goals are related to HRM policies which are expected to produce desirable organisational outcomes.

Guest (1989) describes the four policy goals as follows:

- Strategic integration – ensuring that HRM is fully integrated into strategic planning, that HRM policies are coherent, and that line managers use HRM practices as part of their everyday work.

- Commitment – ensuring that employees feel bound to the organisation and are committed to high performance via their behaviour.

- Flexibility – ensuring an adaptable organisation structure, and functional flexibility based on multiskilling.

- Quality – ensuring a high quality of goods and services through high-quality, flexible employees.

Guest sees these goals as a package – all need to be achieved to create the desired organisational outcomes, which are high job performance, problem solving, change, innovation and cost effectiveness; and low employee turnover, absence and grievances.

Clarity of goals gives a certain attractiveness to this model – but this is where the problems also lie. Whipp (1992) questions the extent to which such a shift is possible, and Purcell (1991) sees the goals as unattainable. The goals are also an expression of human resource management, as opposed to personnel management, and as such bring us back to the debate about what human resource management really is and the inherent contradictions in the approach (Legge 1991, 1995). Ogbonna and Whipp (1999) argue that internal consistency within such a model is extremely difficult to achieve because of such contradictions (for example the tension between flexibility and commitment). Because the prescriptive approach brings with it a set of values, it suggests that there is only one best way and this is it. Although Guest (1987) has argued that there is no best practice, he also encourages the use of the above approach as the route to survival of UK businesses.

Pfeffer (1994) and Becker and Gerhart (1996) are well-known exponents of this view. While there is some support for this perspective, there remains some debate as to which particular human resource practices will stimulate high commitment. We consider this perspective in more depth in Chapter 11 on Strategic aspects of performance.

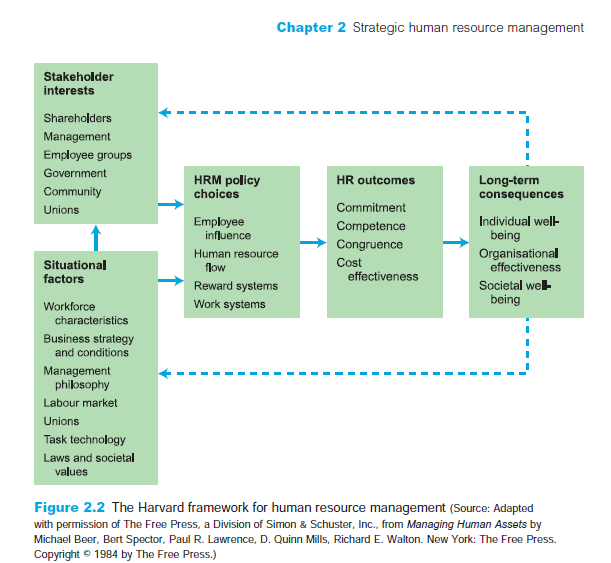

Falling somewhere between the universalist approach and the fit approach is the Harvard model of HRM. This model, produced by Beer et al. (1984), is analytical rather than prescriptive. The model, shown in Figure 2.2, recognises the different stakeholder interests that impact on employee behaviour and performance, and also gives greater emphasis to factors in the environment that will help to shape human resource strategic choices – identified in the Situational factors box. Poole (1990) also notes that the model has potential for international or other comparative analysis, as it takes into account different sets of philosophies and assumptions that may be operating.

Although Beer et al.’s model is primarily analytical, there are prescriptive elements leading to some potential confusion. The prescription in Beer et al.’s model is found in the HR outcomes box, where specific outcomes are identified as universally desirable.

2. Fit or contingency approach

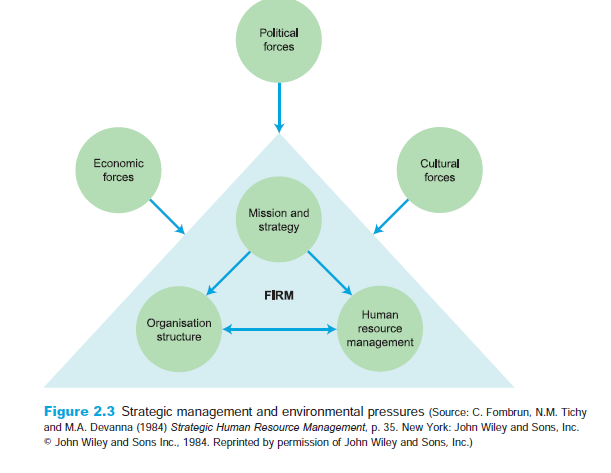

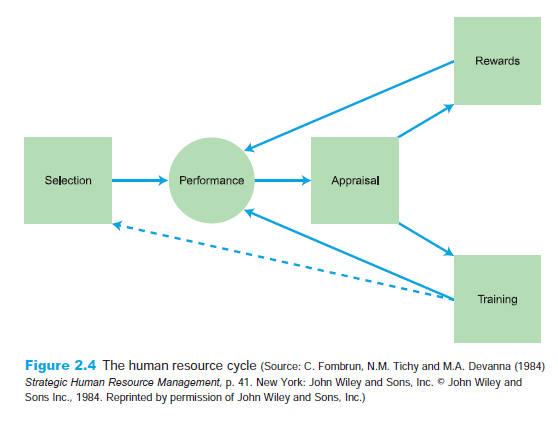

The fit or contingency approach is based on two critical forms of fit. The first is external fit (sometimes referred to as vertical integration) – that HR strategy fits with the demands of business strategy; the second is internal fit (sometimes referred to as horizontal integration) – that all HR policies and activities fit together so that they make a coherent whole, are mutually reinforcing and are applied consistently. One of the foundations of this approach is found in Fombrun et al. (1984), who proposed a basic framework for strategic human resource management, shown in Figures 2.3 and 2.4. Figure 2.3 represents the location of human resource management in relation to organisational strategy, and you should be able to note how the Fit model (B) is used (see Figure 2.1). Figure 2.4 shows how activities within human resource management can be unified and designed in order to support the organisation’s strategy.

The strength of this model is that it provides a simple framework to show how selection, appraisal, development and reward can be mutually geared to produce the required type of employee performance. For example, if an organisation required cooperative team behaviour with mutual sharing of information and support, the broad implications would be:

- Selection: successful experience of teamwork and sociable, cooperative personality; rather than an independent thinker who likes working alone.

- Appraisal: based on contribution to the team, and support of others; rather than individual outstanding performance.

- Reward: based on team performance and contribution; rather than individual performance and individual effort.

There is little doubt that this type of internal fit is valuable. However, questions have been raised over the model’s simplistic response to organisation strategy. The question ‘what if it is not possible to produce a human resource response that enables the required employee behaviour and performance?’ is never addressed. So, for example, the distance between now and future performance requirements, the strengths, weaknesses and potential of the workforce, the motivation of the workforce and employee relations issues are not considered.

This model has been criticised because of its dependence on a rational strategy formulation rather than on an emergent strategy formation approach; and because of the nature of the one-way relationship with organisational strategy. It has also been criticised owing to its unitarist assumptions, as no recognition is made for employee interests and their choice of whether or not to change their behaviour.

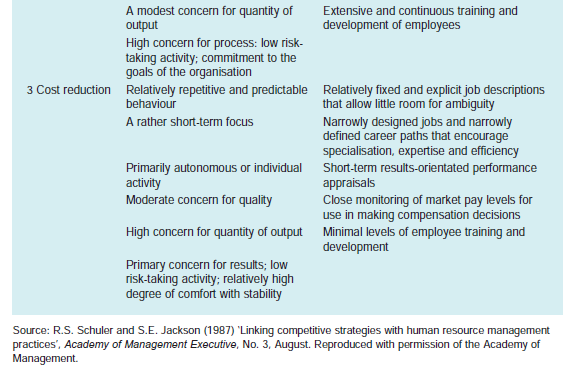

Taking this model and the notion of fit one step further, human resource strategy has been conceived in terms of generating specific employee behaviours. In the ideal form of this there would be analysis of the types of employee behaviour required to fulfil a predetermined business strategy, and then an identification of human resource policies and practices which would bring about and reinforce this behaviour. A very good example of this is found in Schuler and Jackson (1987). They used the three generic business strategies defined by Porter (1980) and for each identified employee role behaviour and HRM policies required. Their conclusions are shown in Table 2.1.

Similar analyses can be found for other approaches to business strategy, for example in relation to the Boston matrix (Purcell 1992) and the developmental stage of the organisation (Kochan and Barocci 1985). Some human resource strategies describe the behaviour of all employees, but others have concentrated on the behaviour of Chief Executives and senior managers; Miles and Snow (1984), for example, align appropriate managerial characteristics to three generic strategies of prospector, defender and analyser. The rationale behind this matching process is that if managerial attributes and skills are aligned to the organisational strategy, then a higher level of organisational performance will result. There is little empirical evidence to validate this link, but work by Thomas and Ramaswamy (1996) does provide some support. They used statistical analysis to investigate if there was a match between manager attributes and skills in organisations with either a defender or a prospector strategy in 269 of the Fortune 500 companies in the United States. They found an overall statistical relationship between manager attributes and strategy. Taking the analysis a step further they then compared 30 organisations which were misaligned with 30 which were aligned and found that performance in the aligned companies (whether prospector or defender) was statistically superior. While this work can be criticised, it does provide an indication of further research which can be developed to aid our understanding of the issues. Sanz-Valle et al. (1999) found some partial support for the Schuler and Jackson model in terms of the link between business strategy and HR practices, but they did not investigate the implications of this link for organisational performance. The types of strategies described above are generic, and there is more concentration in some organisations on tailoring the approach to the particular needs of the specific organisation.

Many human resource strategies aim not just to target behaviour, but through behaviour change to effect a movement in the culture of the organisation. The target is, therefore, to change the common view of ‘the way we do things around here’ and to attempt to manipulate the beliefs and values of employees. There is much debate as to whether this is achievable.

We have previously recounted some of the concerns expressed about Fombrun et al.’s specific model; however, there is further criticism of the fit or matching perspective as a whole. Grundy (1998) claims that the idea of fit seems naive and simplistic. Ogbonna and Whipp (1999) argue that much literature assumes that fit can be targeted, observed and measured and there is an underlying assumption of stability. Given that most companies may have to change radically in response to the environment, any degree of fit previously achieved will be disturbed. Thus, they contend that fit is a theoretical ideal which can rarely be achieved in practice. Boxall (1996) criticises the typologies of competitive advantage that are used, arguing that there is evidence that high-performing firms are good ‘all rounders’; the fact that strategy is a given and no account is taken of how it is formed or by whom; the assumption that employees will behave as requested; and the aim for consistency, as it has been shown that firms use different strategies for different sections of their workforce.

However, in spite of the criticisms of this perspective, it is still employed in both the academic and practitioner literature – see, for example, Holbeche’s (1999) book entitled Aligning Human Resources and Business Strategy.

A further form of fit which we have not mentioned so far is cultural fit, and the Window on Practice, below, demonstrates this aspect.

3. Resource-based approach

The resource-based view of the firm (Barney 1991) has stimulated attempts to create a resource-based model of strategic HRM (Boxall 1996). The resource-based view of the firm is concerned with the relationships between internal resources (of which human resources is one), strategy and firm performance. It focuses on the promotion of sustained competitive advantage through the development of human capital rather than merely aligning human resources to current strategic goals. Human resources can provide competitive advantage for the business, as long as they are unique and cannot be copied or substituted for by competing organisations. The focus is not just on the behaviour of the human resources (as with the fit approach), but on the skills, knowledge, attitudes and competencies which underpin this, and which have a more sustained impact on long-term survival than current behaviour (although this is still regarded as important). Briggs and Keogh (1999) maintain that business excellence is not just about ‘best practice’ or ‘leapfrogging the competition’, but about the intellectual capital and business intelligence to anticipate the future, today.

Barney states that in order for a resource to result in sustained competitive advantage it must meet four criteria, and Wright et al. (1994) demonstrate how human resources meet these. First, the resource must be valuable. Wright and his colleagues argue that this is the case where demand for labour is heterogeneous, and where the supply of labour is also heterogeneous – in other words where different firms require different competencies from each other and for different roles in the organisation, and where the supply of potential labour comprises individuals with different competencies. On this basis value is created by matching an individual’s competencies with the requirements of the firm and/or the job, as individuals will make a variable contribution, and one cannot be substituted easily for another.

The second criterion, rarity, is related to the first. An assumption is made that the most important competence for employees is cognitive ability due to future needs for adaptability and flexibility. On the basis that cognitive ability is normally distributed in the population, those with high levels of this ability will be rare. The talent pool is not unlimited and many employers are currently experiencing difficulties in finding the talent that they require.

Third, resources need to be inimitable. Wright et al. argue that this quality applies to the human resource as competitors will find it difficult to identify the exact source of competitive advantage from within the firm’s human resource pool. Also competitors will not be able to duplicate exactly the resource in question, as they will be unable to copy the unique historical conditions of the first firm. This history is important as it will affect the behaviour of the human resource pool via the development of unique norms and cultures. Thus even if a competing firm recruited a group of individuals from a competitor they would still not be able to produce the same outcomes in the new firm as the context would be different. Two factors make this unique history difficult to copy. The first is causal ambiguity – in other words it is impossible to separate out the exact causes of performance, as the sum is always more than the parts; and, second, social complexity – that the complex of relationships and networks developed over time which have an impact on performance is difficult to dissect.

Finally resources need to be non-substitutable. Wright and his co-authors argue that although in the short term it may be possible to substitute human resources with others, for example technological ones, in the long term the human resource is different as it does not become obsolete (like technology) and can be transferred across other products, markets and technologies.

Wright et al. noted that attention has often been devoted to leaders and top management in the context of a resource-based approach, and indeed Boxall (1996) contends that this approach provides the theoretical base on which to concentrate in the renewal and development of the critical resource of leaders in the organisation. However, Wright and his co-authors view all human resources in the organisation as the pool of capital. This sits well with the view of strategy as evolutionary and strategy being influenced from the bottom up as well as from the top down. Also it is likely that top managers are more easily identified for their contribution to the organisation and hence are more likely to be mobile, therefore, than other employees who may not be so easily identified.

However, different segments of the human resource are viewed differently by organisations in terms of their contribution to competitive advantage, so for some organisations the relevant pool of human capital may not be the total pool of employees.

Whereas fit models focus on the means of competitive advantage (HR practices) the resource-based view focuses on the source (the human capital). Wright et al. argue that while the practices are important they are not the source of competitive advantage as they can be replicated elsewhere, and they will produce different results in different places because of the differential human capital in different places. The relationship between human capital, human resource practices and competitive advantage is shown in Figure 2.5.

Boxall (1996) argues that this theoretical perspective provides a conceptual base for asserting that human resources are a source of competitive advantage, and as such valued as generating strategic capability. Thus there is a case for viewing HR strategy as something more than a reactive matching process. Indeed Wright et al. argue that it provides the case for HR to be involved in the formulation of strategy rather than just its implementation. They suggest that it provides a grounding for asserting that not every strategy is universally implementable, and that alternatives may have to be sought or the human capital pool developed further, via human resource practices, where this is possible.

The importance of this perspective is underlined by the current emphasis on a firm’s intangible assets. Numerous studies have shown that a firm’s market value (the sum of the value of the shares) is not fully explained by its current financial results (see, for example, Ulrich and Smallwood 2002) or its tangible assets and the focus has moved to a firm’s intangible assets such as intellectual capital and customer relationships – all of which are derived from human capital (see, for example, Schmidt and Lines 2002). This emphasis has resulted in a great deal of attention being paid to the evaluation of human capital through measuring, reporting and managing it. Human capital can be reported both internally and externally (as in the annual financial report, or similar), and Angela Baron from the CIPD has been reported as commenting that ‘investors are demanding information on human capital’ (Roberts 2002).

But human capital is loaned: ‘human capital is not owned by the organization, but secured through the employment relationship’ (Scarborough 2003a, p. 2) and because this is so, the strategy for the management of people is also critical. The government’s White Paper, Modernising Company Law, suggested that the largest 1,000 companies should publish an annual operating and financial review (OFR), and experts believed

this would need to include a review about the ways that employees are managed (People Management 2002). However this planned requirement has now been scrapped and a simpler report is now sufficient which meets the minimum demands of the EU Accounts and Modernisation Directive (EAMD) (Scott 2005). The report now required is entitled the ‘Business Review’, forms part of the Director’s Report, and actually came into force in April 2005. The Business Review requires ‘a balanced and comprehensive analysis of the business’, and that human capital management issues should be included ‘where material’. The scrapping of the OFR raised fears that human capital reporting would have less priority in the business; however the Business Review does apply in some form to all organisations except small firms. Angela Baron suggests that the better the information an organisation has on its human capital the more likely it is that business benefits will accrue (Manocha 2006), and it has been suggested that many companies which have prepared for the OFR will go ahead and produce the more extensive report. The Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatary Reform (DBERR) has not discounted the possibility of the OFR being resurrected.

The perceived importance of people as an intangible asset is demonstrated in the action of Barclays Group who on their Investor’s Day were keen to demonstrate not only their financial results but their people strategies and improvements in staff satisfaction which they believe have contributed to the results (Arkin and Allen 2002). The Barclays approach is covered in more detail in a case study on the website www.pearsoned.co.uk/torrington.

This approach has great advantages from an HR point of view. People in the organisation become the focus, their contribution is monitored and made more explicit, the way people are managed can be seen to add value and money spent on people can be seen as an investment rather than a cost. Some firms are using the balanced scorecard to demonstrate the contribution that human capital makes to firm performance, such as Norwich Union, and Scarborough (2003b) argues that this builds a bridge between the role of the HR function and the strategy of the firm. However, there are inbuilt barriers in the language of the resource-based view. One is the reference to people as ‘human capital’ which some consider to be unnecessarily instrumental. Another is the focus on ‘firms’ and ‘competitive advantage’ which makes it harder to see the relevance of this perspective for organisations in the public sector. There is also the issue of what is being measured and who decides this. The risk is that too much time is spent measuring and that not everything that is measured is of critical value to the organisation. So far, such measures appear very varied, although different firms will, of course, need to measure different things. Measures often appear to be taken without a coherent framework, as appears to be the case in the results documented by Scarborough and Elias (2002) for their 10 case study organisations. The balanced scorecard and the HR scorecard, however, appear to be useful mechanisms in this respect. The evaluation of human capital is considered in greater depth in Chapter 33.

4. Why does the theory matter?

It is tempting to think of these theories of strategic HRM as competing with each other. In other words one is right and the others are wrong. If this were the case HR managers/ directors and board members would need only to work out which is the ‘right’ theory and apply that. This is, of course, a gross oversimplification, as each theory can be interpreted and applied in different ways, and each has advantages and disadvantages. It

could be argued that different theories apply in different sectors or competitive contexts. For example Guest (2001) suggests that there is the possibility that a ‘high performance/high commitment’ approach might always be most appropriate in manufacturing, whereas strategic choice (which could be interpreted as choice to fit with business strategy) might be more realistic in the services sector. This could be taken one step further to suggest that different theories apply to different groups in the workforce.

Consequently, these three theories do not necessarily represent simple alternatives. It is also likely that some board directors and even HR managers are not familiar with any of these theories (see, for example, Guest and King 2001). In spite of that, organisations, through their culture, and individuals within organisations operate on the basis of a set of assumptions, and these assumptions are often implicit. Assumptions about the nature and role of human resource strategy, whether explicit or implicit, will have an influence on what organisations actually do. Assumptions will limit what are seen as legitimate choices.

Understanding these theories enables HR managers, board members, consultants and the like to interpret the current position of HR strategy in the organisation, confront current assumptions and challenge current thinking and potentially open up a new range of possibilities.

This chapter forms the underpinning for the other strategic chapters later in the book and links with key material in Chapter 3 on HR planning, Chapter 14 on Leadership and change, Chapter 32 on The changing HR function and Chapter 33 on IT and human capital measurement.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I like this web blog very much so much fantastic information.

Good site! I truly love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I’m wondering how I could be notified when a new post has been made. I’ve subscribed to your RSS which must do the trick! Have a great day!

It’s actually a great and helpful piece of information. I’m glad that you shared this useful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.