Despite wide differences among national laws, there is a high degree of uniformity in contract practices for the export and import of goods. The universality of trade practices, including terms of sale, is due to the development of the law merchant by international mercantile custom. The law merchant refers to the body of commercial law that developed in Europe during the medieval period for merchants and their merchandise (Brinton, Christopher, Wolff, and Winks, 1984).

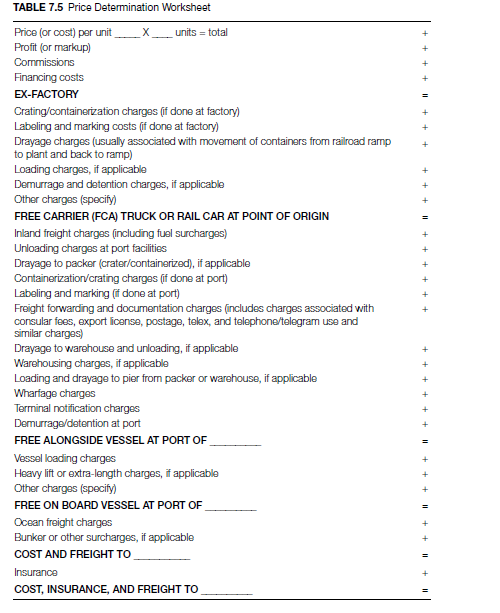

Trade terms are intended to define the method of delivery of the goods sold and the attendant responsibilities of the parties. Such terms also help the seller in the calculation of the purchase price (Anonymous, 1993). A seller quoting the term of sale as FOB, for example, will evidently charge a lower price than one quoting CIF because the latter includes not only the cost of goods but also expenses incurred by the seller for insurance and freight to ship the goods to the port of destination.

1. The Purpose and Function of Incoterms

Incoterms (International commercial terms) comprise a body of predefined commercial terms that deal with the seller’s delivery obligation under an international sales contract. The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), a nongovernmental entity, has been responsible for the development of Incoterms and has undertaken seven revisions since 1936 (1953, 1967, 1976, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010) to make the terms adaptable to changes in global trade, technology, and contemporary commercial practice. Incoterms are accepted by businesses and governments all over the world, thus setting the standard for the interpretation of trade terms used in domestic and international trade. The most recent revision (2010) was necessitated by certain significant and rapid changes in the global economy: (1) The need to adapt trade terms to domestic and international commercial practice as well as to developments in national accounting standards (GAAP or IFRS) and to domestic law in important trading nations such as the United States (Uniform Commercial Code, Sarbanes-Oxley); (2) the desire to increase participation and input from emerging nations that are significant players in global trade such as Brazil and China; (3) the increased importance of multimodal transportation and the need for a broader scope of shipping terms to address land, ocean, and air movements. The current revision of Incoterms was published and came into effect on January 1, 2011 (Reference Guide, Table 7.3).

Incoterms comprise a set of rules and not laws. It is neither national legislation nor an international treaty. However, when parties to an international sales contract agree to be governed by Incoterms, the terms take on the force of law and questions pertaining to delivery of goods will be interpreted according to Incoterms. If the parties do not explicitly agree to be governed by Incoterms, this could be made an implicit term of the contract as part of international custom.

Businesses that understand the implications of Incoterms excel at facilitating the movement of goods, stabilize lead times, and often reduce the landed cost of merchandise. This could serve as a source of competitive advantage (International Perspectives 7.1 and 7.2). In short, Incoterms accomplish the following objectives:

- Provide a set of international rules for the interpretation of the most commonly used terms of sale

- Reduce uncertainty arising from different interpretation of such terms in different countries

- Define the rights and obligations of the parties to the contract of sale pertaining to the delivery of goods sold

- Clearly delineate the tasks, costs, and risks associated with the transportation and delivery of goods.

The national laws of each country often determine the rights and duties of parties with respect to terms of sale. In the United States, the Revised American Foreign Trade Definitions (1941) and the Uniform Commercial Code govern terms of sale. Since 1980, the sponsors of the Revised American Foreign Trade Definitions recommend the use of Incoterms.

In order to avoid any misunderstanding, parties to export contracts should always state the application of the current version of Incoterms. The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) and Incoterms complement each other in many areas. Trade terms are not understood in the same manner in every country, and it is important to explicitly state the law that governs the contract. For example, a contract should state FOB New York (Incoterms) or “CIF Liverpool (Uniform Commercial Code).”

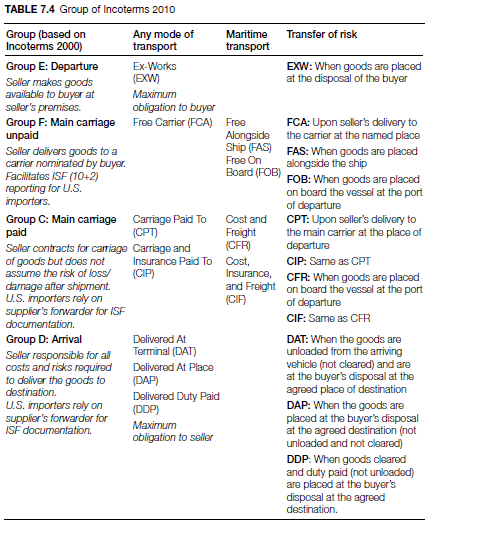

All trade terms are classified into four groups based on the point of transfer of risk (delivery) from seller to buyer. They are displayed in order of increasing obligations for the seller. This means that the Group E term such as Ex-Works signifies the least obligation to the seller, whereas the Group D term imposes the maximum amount of responsibility on the seller (Tables 7.3 and 7.4).

- Group E term (Ex-Works): This grouping has only one term and represents the seller’s minimum obligation—to place the goods at the disposal of the buyer. There are no contractual arrangements between seller and buyer with regard to insurance, transportation or export.

- Group F terms (FCA, FAS, FOB): The seller is expected to bear the risk and expense of delivery to a nominated carrier. It is the buyer’s responsibility to arrange and pay for the main carriage to the point of destination.

- Group C terms (CFR, CIF, CPT, CIP): C terms establish the point of delivery (transfer of risk) from seller to buyer at the point of shipment. It, however, extends the seller’s obligation with regard to the costs of carriage and insurance up to the point of destination. This means that the seller bears certain costs even after the critical point for the division of the risk or damage to the goods. These are often referred to as shipment terms.

- Group D terms (DAT, DAP, DDP): The seller’s delivery obligation extends to the country of destination. This means that the seller could be held liable for breach of contract if the goods are lost or damaged after shipment but before arrival at the agreed point of destination. The seller may be required to provide substitute goods or other forms of restitution to the buyer. These are often referred to as arrival terms. It is not ideal for letter-of-credit transactions since the bill of lading or air waybill do not show actual arrival.

Incoterms 2010 consists of eleven terms and are divided into two major groups:

- Group for any mode of transport: This includes trade terms used for carriage by road, rail, air, and multimodal: Ex-Works (EXW), Free Carrier (FCA), Carriage Paid To (CPT), Carriage and Insurance Paid To (CIP), Delivered At Terminal (DAT), Delivered At Place (DAP), and Delivered Duty Paid (DDP).

- Group for maritime transport: Trade terms under this group are used for carriage over water from port to port, including inland waterways. They include Free Alongside Ship (FAS), Free On Board (FOB), Cost and Freight (CFR), and Cost, Freight, and Insurance (CIF).

2. Incoterms and Scope of Coverage

Incoterms cover only the delivery-oriented aspects of an international sales contract. The seller’s delivery obligations include responsibility for risk of loss or damage to the goods and transportation and customs-related costs, as well as other functional responsibilities (e.g., packaging, export clearance, contract of carriage). Incoterms, however, do not cover or address the following areas:

- Transfer of title: Incoterms do not deal with transfer of ownership of goods (Gardner, 2011)

- Payment terms or methods: Incoterms do not address matters pertaining to payment terms such as cash in advance or letter of credit. Such issues must be covered with a separate clause in the contract of sale.

- Remedies for breach of contract: Incoterms do not cover consequences for breach of contract.

- Any other nondelivery related issues: Incoterms are not a substitute for contracts of carriage or insurance. These questions must be addressed in a separate contract.

3. The Concept of Delivery Under Incoterms

Seller’s delivery obligations under Incoterms do not always entail the physical transfer of possession of goods to the buyer (Chikwava, 2012). There are many cases where such delivery is completed well before the arrival of goods at destination. Incoterms links delivery to the risk of loss or damage to the goods. This means that seller’s delivery obligation is completed at the point where risk of loss or damage to the merchandise is transferred from the seller to the buyer. In CIF contracts, for example, delivery takes place when the goods are placed on board the ship at the port of departure, while in FCA contracts such delivery (transfer of risk) takes place when the goods have been delivered to the carrier at the named place (Table 7.5).

4. Incoterms 2012: Trade Terms

All trade terms are classified into four groups based on the concept of progressive delivery responsibility of the seller. Such terms provide a standardized, universal set of shipping terms that is consistent with contemporary business practices and modes of transportation for domestic and international shipments (Roos, 2011).

4.1. Group E (Ex-Works [EXW])

Ex-Works, Ex-Warehouse, Ex-Store (namedplace): Under this term, the buyer or agent must collect the goods at the seller’s works, warehouse, or store. The seller bears all risk and expenses until the goods are placed at the disposal of the buyer at the time and place agreed for delivery, normally the seller’s premises, warehouse, or factory. The seller has no obligation to load the goods.

Risk is not transferred to buyer if damage or loss is attributed to the failure on the part of the seller to deliver the goods in conformity with the contract (e.g., damage due to inadequate packing of goods).

The buyer bears all risk and charges pertaining to preshipment inspection, export/import licenses, and customs duties/taxes needed for exportation. The buyer is also responsible for clearance of goods for exports, transit, and imports, since the seller makes the goods available to buyer in the country of export.

This term of sale is similar to a domestic sales transaction, although the product is destined for export. This term may be out of line with international business practice since many countries require exporters to be responsible for export clearance or compliance with export regulations. There may be concern with diversion of goods since the buyer is the party that is responsible for export and documentation. Furthermore, there is no standard as to what document constitutes evidence of delivery.

4.2. Group F (FCA, FAS, and FOB)

Free Carrier (FCA), named place: The seller bears the risk and costs relating to the goods until delivery to the carrier or any other person nominated by the buyer. The place of delivery could be the carrier’s cargo terminal or a vehicle sent to pick up the goods at the seller’s premises. In the latter case, the seller is responsible for loading the goods onto the buyer’s collecting vehicle. If the place of delivery is the carrier’s cargo terminal, the seller is required only to bring the goods to the terminal (but is not obligated to unload them). It is thought that the carrier is more likely to have the necessary personnel and equipment to unload the goods at its own terminal than is the seller.

The carrier nominated by the buyer could be a trucker, a freight forwarder, a steamship line, or an airline. The seller must fulfill the export formalities. FCA is suitable for carriage by road, rail, air, and multimodal transport, in particular when containers are being used.

Upon delivery of the goods to the carrier, the seller receives (from the carrier) a receipt that serves as evidence of delivery and contract of carriage made on behalf of the buyer. Neither party is required to insure under FCA. However, the seller must provide the buyer (upon request) with the necessary information for procuring insurance. When using full container load (FCL), risk of loss shifts to the buyer once the goods are loaded, primarily in the factory or on the seller’s premises. In the case of less than full container load (LCL), risk is transferred after the goods are delivered to the groupage warehouse named by the buyer. Similar to FAS and FOB terms, FCA covers only pre-transport (main transport risk lies with buyer). If the seller arranges and pays for carriage and insurance, it turns into CIP (cost and insurance paid to) shipment (CPT without insurance) (Table 7.5).

Besides payment of the purchase price as provided in the contract, the buyer has the following obligations:

- Obtain at his or her own risk and expense any import license and other official authorization necessary for importation of the goods as well as for their transit through another country

- Contract at his or her own expense for carriage of the goods from the named place of delivery

- Pay the costs of any preshipment inspection except when such inspection is mandated by the exporting country.

Free Alongside Ship (FAS), named port of shipment: This term requires the seller to deliver the goods to a named port alongside a vessel to be designated by the buyer (International Chamber of Commerce, 2010). “Alongside the vessel” has been understood to mean that the goods must be within reach of a ship’s lifting tackle. The risks to the goods pass to the buyer upon the seller’s delivery alongside the ship. This implies that all charges and risks for the goods are borne by the buyer from the time they have been effectively delivered alongside the vessel.

The seller must obtain at his or her own risk and expense any export license and other official authorizations, including customs formalities, that are necessary for the export of the goods. The seller’s obligation to clear the goods for export is similar to that in FOB contracts. There is an implied duty on the part of the seller to cooperate in arranging a loading and shipping schedule and to render at the buyer’s request and expense every assistance in obtaining necessary documents for the import of the goods and their transit through another country. The seller must provide the buyer (at the seller’s own expense) with the usual proof of delivery.

The buyer must contract (at his or her own expense) for the carriage of goods from the port of shipment. Since the buyer has to nominate the ship, the buyer has to pay any additional costs incurred if the named vessel fails to arrive on time or the vessel is unable to take the goods. In such cases, a premature passing of risk will occur. Costs of any preshipment inspection are borne by the buyer except when such inspection is mandated by the exporting country.

The use of FAS is appropriate in cases where sellers took their shipments to the pier and deposited it close enough for loading. However, nowadays most of the outbound cargo is delivered to ship lines days before placement alongside the vessel. It is also not applicable in cases of rolling cargo (cars, trucks) that can be driven aboard vessel or for ports with shallow harbors that do not allow for vessels to come alongside the pier. FAS terms are often used for oversized cargo such as heavy equipment in oil and gas or mining that require special handling during loading or transit. The seller does not wish to assume the risk of loss during loading of the vessel.

Free On Board (FOB), named port of shipment: The central feature of FOB contracts is the notion that the seller undertakes to place the goods on board the ship designated by the buyer. This includes responsibility for all charges incurred up to and including delivery of the goods over the ship’s rail at the named port of shipment (ICC, 2010). The buyer has to nominate a suitable ship and inform the seller of its name, as well as the loading point and delivery time. If the ship that was originally nominated is unable or unavailable to receive the cargo at the agreed time for loading, the buyer has to nominate a substitute ship and pay all additional charges. Once the seller delivers the goods on board the ship, the buyer is responsible for all subsequent charges such as freight, marine insurance, unloading charges, import duties, and other expenses due on arrival at the port of destination. Unless otherwise stated in the contract of sale, it is customary in FOB contracts for the seller to procure the export license and other formalities necessary for the export of the goods since the seller is more familiar with licensing practices and procedures in the exporting country than the buyer. Transfer of risk occurs upon seller’s delivery of the goods on board the vessel. The seller and buyer need to agree on what constitutes loading on board the vessel since different products are loaded differently. The seller is responsible for performance of the carrier loading the ship even though the latter is chosen by the buyer (ICC, 2010).

The seller’s responsibility for loss or damage to the goods terminates on delivery to the carrier.

FOB does not appear to be consistent with current practice except for shipments of noncontainerized or bulk cargo as well as shipments by chartered vessel. In many other cases, sellers are required to deliver their outbound cargo to ship lines days before actual loading of the cargo. It is a common term used with letter-of-credit transactions.

4.3. Group C (CFR, CIF, CPT, CIP)

Cost, insurance, and freight (CIF), named port of destination: The CIF contract places upon the seller the obligation to arrange for shipment of the goods. The seller has to ship goods described under the contract to be delivered at the destination and arrange for insurance to be available for the benefit of the buyer or any other person with insurable interest in the goods. In the absence of express agreement, the insurance shall be in accordance with minimum of cover provided under the Institute of Cargo Clauses or similar set of guidelines. The cost of freight is borne by the seller (ICC, 2010). The seller must notify the buyer that the goods have been delivered on board the vessel to enable the buyer to receive the goods.

The seller has to tender the necessary documents (commercial invoice, bill of lading, and policy of insurance) to the buyer so that the latter can obtain delivery upon arrival of the goods or recover for their loss. The buyer must accept the documents when tendered by the seller when they are in conformity with the contract of sale and pay the purchase price. Import duties and licenses, consular fees, and charges to procure a certificate of origin are the responsibility of the buyer, while export licenses and other customs formalities necessary for the export of the goods have to be obtained by the seller.

The CIF contract may provide certain advantages to the overseas customer because the seller often possesses expert knowledge and experience to make favorable arrangements with respect to freight, insurance, and other charges. This could be reflected in terms of reduced import prices for the overseas customer.

Under a CIF contract, risk passes to the buyer upon delivery, that is, when the goods are put on board the ship at the port of departure.

Rejection of documents versus rejection of goods: When proper shipping documents that are in conformity with the contract are tendered, the buyer must accept them and pay the purchase price. The right to reject the goods arises when they are landed and, after examination, are found not to be in conformity with the contract. The buyer can claim damages for breach of contract relating to the goods. The buyer’s acceptance of conforming documents does not impair subsequent rejection of the goods and recovery of the purchase price if upon arrival the goods are not in accordance with the terms of sale. It may also happen that while the goods conform to the contract, the documents are not in accordance with the contract of sale (discrepancies between documents such as bill of lading, commercial invoice, draft, and the letter of credit or contract of sale). In this case, the buyer may waive the discrepancies and agree to accept the goods. Thus, under a CIF contract, the right to reject the documents is separate and distinct from the right to reject the goods.

Payment is often made against documents. Tender of the goods cannot be an alternative to tender of the documents in CIF contracts.

Loss of goods: If the goods shipped under a CIF contract are destroyed or lost during transit, the seller is entitled to claim the purchase price against presentation of proper shipping documents to the buyer. Since insurance is taken for the benefit of the buyer, the buyer can claim against the insurer insofar as the risk is covered by the policy. If the loss is due to some misconduct on the part of the carrier that is not covered by the policy, the buyer can recover from the carrier. CIF is better suited for bulk cargo but not for containerized shipments, since the latter are delivered at port terminal and not loaded onto the vessel by the seller. CIF is a common term used with letter of credit transactions (seller keeps control of shipping terms specified in the letter of credit).

The only difference between CIF and CFR term is that the latter does not require the seller to obtain and pay for cargo insurance.

Carriage Paid To (CPT), named place of destination: This is similar to the CFR term, except that it may be used for any other type of transportation. Even though the seller is obligated to arrange and pay for the transportation to a named place of destination, he or she completes delivery obligations and thus transfers risk of loss or damage to the buyer when the goods are delivered to the first carrier (named by the seller) at the place of shipment. The seller pays the main carriage to destination but does not carry the transport risk.

The seller must notify the buyer that the goods have been delivered to the carrier (first carrier in the case of multimodal transportation) and also give any other notice required to enable the buyer to take receipt of the goods. The term is appropriate for multimodal transportation. When several carriers are involved (precarriage by road or rail from the seller’s warehouse for further carriage by sea to the destination), the seller has fulfilled his or her delivery obligation under the CPT term when the goods have been handed over for carriage to the first carrier. In CFR and CIF contracts, delivery is not completed until the goods have reached a vessel at the port of shipment.

In the absence of an explicit agreement between the parties, there is no requirement to provide a negotiable bill of lading (to enable the buyer to sell the goods in transit). The buyer must pay the costs of any preshipment inspection unless such inspection is mandated by the exporting country. The CPT term is similar to the CIP term, except that the seller is not required to arrange or pay for insurance coverage of the goods during transportation. CPT is the nonmaritime counterpart of CFR and is better suited to container transport.

4.4. Group D (DAT, DAP, DDP)

All Group D terms can be used with all modes of transport. These terms share certain common features:

- They are arrival/destination terms.

- The seller is required to arrange for transportation, pay the freight, and bear the risk of loss to a named point of destination.

- The seller must place the goods at the disposal of the buyer (varies according to term).

- There is no requirement for use of negotiable bill of lading, and delivery occurs only after arrival of the goods.

- Incoterms do not require insurance during transportation. The seller may have to arrange and pay for insurance or act as self-insurer during transportation.

- The buyer must pay the costs of any preshipment inspection except when such inspection is mandated by the exporting country. There are no provisions for postshipment inspection.

Delivered At Terminal (DAT) (named terminal at port or place at destination): DAT is a new addition to Incoterms 2010 and applies to all modes of transport. It replaces the DEQ (delivery ex-quay) term and provides more flexibility. Risk of loss is transferred to the buyer when goods are delivered at a named terminal, yard, or warehouse (offloaded) at the named port or place of destination. The seller is responsible for export clearance and transport costs up to the named place of destination. The customer is responsible for customs clearance, duties, and taxes. This term is included in light of the recognition that most air and ocean shipments are offloaded to a secondary location at destination. It works well for LCL or consolidation shipments (International Perspective 7.3).

Delivered At Place (DAP) (named place of destination): DAP term is similar to DAT except that in the case of DAP the buyer is responsible for unloading the goods at the named place of destination. DAP is used when buyer provides equipment such as forklifts for unloading.

Delivery Duty Paid (DDP) (named place of destination): DDP is similar to DAP except that the seller bears the costs and risks involved to bring the goods, including duties and taxes for import in the country of destination. It is suitable for courier shipments of low value. It is risky for exporters since they have to deal with foreign customs practices that are not familiar to them.

The major differences between arrival contracts and CIF contracts are as follows:

- In arrival contracts, delivery is effected when the goods are placed at the disposal of the buyer. In CIF term, delivery is effected upon loading the goods on board the vessel at the port of departure.

- In arrival contracts, the buyer is under no obligation to pay the purchase price if the goods are lost in transit. In CIF contracts, the buyer is required to pay against documents. However, the loss of goods gives the buyer the right of claim from the carrier or the insurance company, depending on the circumstances.

Source: Seyoum Belay (2014), Export-import theory, practices, and procedures, Routledge; 3rd edition.

Sweet blog! I found it while browsing on Yahoo News. Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there! Cheers

Wow! This blog looks exactly like my old one! It’s on a entirely different topic but it has pretty much the same layout and design. Wonderful choice of colors!

Thank you for writing about this topic. Your post really helped me and I hope it can help others too.

Thanks for writing this article. It helped me a lot and I love the subject.

I must say you’ve been a big help to me. Thanks!

I’ve to say you’ve been really helpful to me. Thank you!

Thank you for posting such a wonderful article. It helped me a lot and I appreciate the topic.