A trademark is any word, name, symbol, or device used to identify the source or origin of products or services and to distinguish those products or services from others. All businesses want to be recognized by their potential clientele and use their names, logos, and other distinguishing features to enhance their visibility. Trademarks also provide consumers with useful information. For example, con- sumers know what to expect when they see a Macy’s store in a mall. Think of how confusing it would be if any retail store could use the name Macy’s.

As is the case with patents, trademarks have a rich history. Archaeologists have found evidence that as far back as 3,500 years ago, potters made distinc- tive marks on their articles of pottery to distinguish their work from others. But consider a more modern example. The original name that Jerry Yang and David Filo, the co-founders of Yahoo, selected for their Internet directory service was “Jerry’s Guide to the World Wide Web.” Not too catchy, is it? The name was later changed to Yahoo, which caught on with early adopters of the Internet.

1. The Four types of trademarks

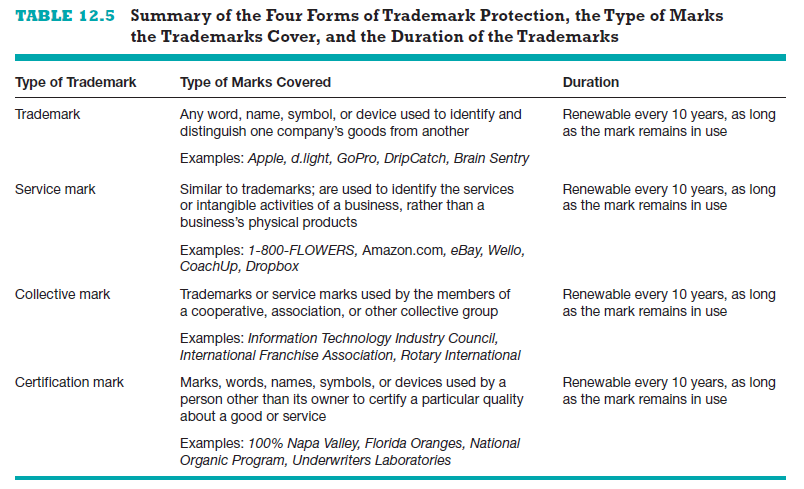

There are four types of trademarks: trademarks, service marks, collective marks, and certification marks (see Table 12.5). Trademarks and service marks are of the greatest interest to entrepreneurs.

Trademarks, as described previously, include any word, name, symbol, or device used to identify and distinguish one company’s products from an- other’s. Trademarks are used to promote and advertise tangible products.

Examples here include Apple for smartphones, Nike for athletic shoes, Ann Taylor for women’s clothing, and Zynga for online games.

Service marks are similar to ordinary trademarks, but they are used to identify the services or intangible activities of a business rather than a busi- ness’s physical product. Service marks include The Princeton Review for test prep services, eBay for online auctions, and Verizon for cell phone service.

Collective marks are trademarks or service marks used by the members of a cooperative, association, or other collective group, including marks indi- cating membership in a union or similar organization. The marks belonging to the American Bar Association, The International Franchise Association, and the Entrepreneurs’ Organization are examples of collective marks.

Finally, certification marks are marks, words, names, symbols, or devices used by a person other than its owner to certify a particular quality about a product or service. The most familiar certification mark is the UL mark, which certifies that a product meets the safety standards established by Underwriters Laboratories. Other examples are the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval, Stilton Cheese (a product from the Stilton region in England), and 100% Napa Valley (from grapes grown in the Napa Valley of northern California).

2. What is protected under trademark law?

Trademark law, which falls under the Lanham Act, passed in 1946, protects the following items:

■ Words: All combinations of words are eligible for trademark registration, including single words, short phrases, and slogans. Birchbox, Warby Parker, and the National Football League are examples of words and phrases that have been registered as trademarks.

■ Numbers and letters: Numbers and letters are eligible for registration.

Examples include 3M, Boeing 787, and AT&T. Alphanumeric marks are also registerable, such as 1-800-CONTACTS.

■ Designs or logos: A mark consisting solely of a design, such as the Golden Gate Bridge for Cisco Systems or the Nike swoosh logo, may be eligible for registration. The mark must be distinctive rather than generic. As a result, no one can claim exclusive rights to the image of the Golden Gate Bridge, but Cisco Systems can trademark its unique depiction of the bridge. Composite marks consist of a word or words in conjunction with a design. An example is the trademark for Zephyrhill’s bottled water, which includes Zephyrhill’s name below a picture of mountain scenery and water.

■ Sounds: Distinctive sounds can be trademarked, although this form of trademark protection is rare. Recognizable examples of such sounds include MGM’s lion’s roar, the familiar four-tone sound that accompanies “Intel Inside” commercials, and the Yahoo yodel.

■ Fragrances: The fragrance of a product may be registerable as long as the product is not known for the fragrance or the fragrance does not enhance the use of the product. As a result, the fragrance of a perfume or room deodorizer is not eligible for trademark protection, whereas stationery treated with a special fragrance in most cases would be.

■ Shapes: The shape of a product, as long as it has no impact on the prod- uct’s function, can be trademarked. The unique shape of the Apple iPod has received trademark protection.20 The Coca-Cola Company has trade- marked its famous curved bottle. The shape of the bottle has no effect on the quality of the bottle or the beverage it holds; therefore, the shape is not functional.

■ Colors: A trademark may be obtained for a color as long as the color is not functional. For example, Nexium, a medicine pill that treats acid reflux disease, is purple and is marketed as “the purple pill.” The color of the pill has no bearing on its functionality; therefore, it can be protected by trademark protection.

■ Trade dress: The manner in which a product is “dressed up” to appeal to customers is protectable. This category includes the overall packag- ing, design, and configuration of a product. As a result, the overall look of a business is protected as its trade dress. In a famous case in 1992, Two Pesos, Inc., v. Taco Cabana International Inc., the U.S. Supreme Court protected the overall design, colors, and configuration of a chain of Mexican restaurants from a competitor using a similar decor.21

Trademark protection is very broad and provides many opportunities for businesses to differentiate themselves from one another. The key for young entrepreneurial firms is to trademark their products and services in ways that draw positive attention to them in a compelling manner.

3. Exclusions from trademark protection

There are notable exclusions from trademark protection that are set forth in the U.S. Trademark Act:

■ Immoral or scandalous matter: A company cannot trademark immoral or scandalous matter, including profane words.

■ Deceptive matter: Marks that are deceptive cannot be registered. For ex- ample, a food company couldn’t register the name “Fresh Florida Oranges” if the oranges weren’t from Florida.

■ Descriptive marks: Marks that are merely descriptive of a product or service cannot be trademarked. For example, an entrepreneur couldn’t design a new type of golf ball and try to obtain trademark protection on the words golf ball. The words describe a type of product rather than a brand of product, such as Titleist or Taylor Made, and are needed by all golf ball manufacturers to be competitive. This issue is a real concern for the manufacturers of very popular products. At one point, Xerox was in danger of losing trademark protection for the Xerox name because of the common use of the word Xerox as a verb (e.g., “I am go- ing to Xerox this”).

■ Surnames: A trademark consisting primarily of a surname, such as Anderson or Smith, is typically not protectable. An exception is a surname combined with other wording that is intended to trademark a distinct product, such as William’s Fresh Fish or Smith’s Computer Emporium.

4. The process of obtaining a trademark

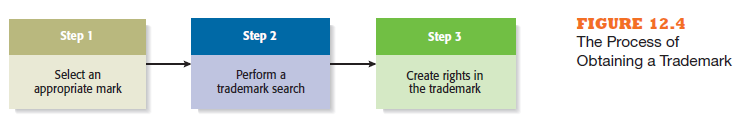

As illustrated in Figure 12.4, selecting and registering a trademark is a three- step process. Once a trademark has been used in interstate commerce, it can be registered with the USPTO. It can remain registered forever as long as the trademark stays in use. The first renewal is between the fifth and the sixth year following the year of initial registration. It can be renewed every 10 years thereafter, as long as the trademark stays in use.

Technically, a trademark does not need to be registered to receive protec- tion and to prevent other companies from using confusingly similar marks. Once a mark is used in commerce, such as in an advertisement, it is protected. There are several distinct advantages, however, in registering a trademark with the USPTO: Registered marks are allowed nationwide priority for use of the mark, registered marks may use the federal trademark registration symbol (®), and registered marks carry with them the right to block the importation of infringing goods into the United States. The right to use the trademark regis- tration symbol is particularly important. Attaching the trademark symbol to a product (e.g., My Yahoo!®) provides notice of a trademark owner’s registration.

This posting allows an owner to recover damages in an infringement action and helps reduce an offender’s claim that it didn’t know that a particular name or logo was trademarked.

There are three steps in selecting and registering a trademark:

Step 1 Select an appropriate mark. There are several rules of thumb to help business owners and entrepreneurs select appropriate trade- marks. First, a mark, whether it is a name, logo, design, or fragrance, should display creativity and strength. Marks that are inherently distinctive, such as the McDonald’s Golden Arches; made-up words, such as Google and eBay; and words that evoke particular images, such as Double Delight Ice Cream, are strong trademarks. Second, words that create a favorable impression about a product or service are helpful. A name such as Safe and Secure Childcare for a day care center positively resonates with parents.

Step 2 Perform a trademark search. Once a trademark has been selected, a trademark search should be conducted to determine if the trade- mark is available. If someone else has already established rights to the proposed mark, it cannot be used. There are several ways to con- duct a trademark search, from self searches to hiring a firm special- izing in trademark clearance checks. The search should include both federal and state searches in any states in which business will be conducted. If the trademark will be used overseas, the search should also include the countries where the trademark will be used.

Although it is not necessary to hire an attorney to conduct a trademark search, it is probably a good idea to do so. As noted above, self searches can also be conducted. The USPTO’s website provides a powerful trademark search engine at www.uspto.gov/trademarks. There is a catch. The USPTO’s search engine only searches trade- marks that are registered. In the United States, you are not required to register a trademark to obtain protection. A trademark attorney can perform a more comprehensive search for you if you think it is necessary. Adopting a trademark without conducting a trademark search is risky. If a mark is challenged as an infringement, a com- pany may have to destroy all its goods that bear the mark (including products, business cards, stationery, signs, and so on) and then se- lect a new mark. The cost of refamiliarizing customers with an exist- ing product under a new name or logo could be substantial.

Step 3 Create rights in the trademark. The final step in establishing a trademark is to create rights in the mark. In the United States, if the trademark is inherently distinctive (think of Starbucks, iTunes, or Facebook), the first person to use the mark becomes its owner. If the mark is descriptive, such as “Bufferin” for buffered aspirin, using the mark merely begins the process of developing a secondary meaning necessary to create full trademark protection. Secondary meaning arises when, over time, consumers start to identify a trademark with a specific product. For example, the name “chap stick” for lip balm was originally considered to be descriptive, and thus not afforded trademark protection. As people started to think of “chap stick” as lip balm, it met the threshold of secondary meaning, and the name “ChapStick” was able to be trademarked.

There are two ways that the USPTO can offer further protection for firms con- cerned about maintaining the exclusive rights to their trademarks. First, a per- son can file an intent-to-use trademark application. This is an application based on the applicant’s intention to use a trademark. Once this application is filed, the owner obtains the benefits of registration. The benefits are lost, however, if the owner does not use the mark in business within six months of registration. Further protection can be obtained by filing a formal applica- tion for a trademark. The application must include a drawing of the trademark and a filing fee, ranging from $275 to $375, depending on how the applica- tion is filed. (It’s cheaper to file electronically.) After a trademark application is filed, an examining attorney at the USPTO determines if the trademark can be registered. It currently takes about 10 months to get a trademark registered through the USPTO.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Its like you read my mind! You seem to know so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a little bit, but instead of that, this is excellent blog. A fantastic read. I’ll certainly be back.