There has been a considerable shift in the way that individual development is understood and characterised. We have moved from identifying training needs to identifying learning needs, the implication being that development is owned by the learner with the need rather than by the trainer seeking to satisfy that need. This also has implications for who identifies the needs and the way that those needs are met. Current thinking suggests that needs are best developed by a partnership between the individual and the organisation, and that the methods of meeting these needs are not limited only to formal courses, but to a wide range of on-the-job development methods and distance/ e-learning approaches. Whilst a partnership approach is considered ideal the phrase ‘self-development’ is an important one in our development lexicon, indicating the growing emphasis on the individual having ownership of and taking responsibility for their own development. There has also been a shift in the type of skills that are the focus of development activity. Hallier and Butts (1999) for example identify a change from an interest in technical skills to the development of personal skills, self-management and attitudes. Lastly, while the focus on development for the current job remains high, there is greater pressure for development which is also future oriented. These shifts reflect the changes that we have already discussed in terms of global competition, fast and continuous change and the need for individuals to develop their employability in an increasingly uncertain world.

1. THE NATURE OF LEARNING

For the purpose of this text we consider the result of learning to be changed or new behaviour resulting from new or reinterpreted knowledge that has been derived from an external or internal experience. There are broadly four theoretical approaches or perspectives to understanding the nature of learning, and the training and development that organisations carry out reflect the explicit or implicit acceptance of one or more perspectives. We will look at each perspective, in the evolutionary order in which they became important. There is no right or wrong theory – each has strengths and weaknesses.

The behaviourist perspective is the earliest which, reflecting the label, concentrates on changes in observable behaviour. Experiments with animals formed the foundation of this theory, for example the work of Skinner, Watson and Pavlov. Researchers sought to associate rewards with certain behaviours in order to increase the display of that behaviour. The relevance of this for organisations today may be seen for example in telesales training where employees are taught to follow a script and calls are listened to, to ensure that the script is followed. Reward or punishment follows depending on behaviour. Trainers are not interested in what is going on in the heads of employees, they merely want them to follow the routine to be learned. This approach has also been used for a range of interpersonal skills training. One American company, for example plays video sequences to trainees portraying the ‘correct’ way to carry out, say, a return to work interview. Trainees then practise copying what they have seen and are given cue cards to use when carrying out that particular interpersonal event. The problems with the perspective are that it is overtly manipulative, simplistic and limited. It may produce only temporary changes in behaviour and increase cynicism.

Cognitive approaches are based on an information-processing perspective and are more concerned with what goes on in the learner’s head. This is a more technical perspective and maps out the stages of learning such as: expectancy to learn (motivation); attention and perception required; experience is coded (meaning is derived); meaning is stored in long-term memory; meaning is retrieved when needed; learning is applied; feedback is received (which may supply reinforcement). The strengths of this perspective are that it stresses the importance of learner motivation and individual needs, it recognises that the individual has some control over what is learned and it identifies feedback as an important aspect of learning. The weaknesses are that it assumes learning is neutral and unproblematic and it is a purely rational approach that ignores emotion. From this perspective useful development activities would be seen as formal courses offering models and ideas with lots of back-up paperwork. Activities to improve learning motivation are also important, for example helping employees to recognise their own development needs and providing rewards for skills development. Mechanisms for providing feedback to employees are also key.

The third perspective is based on social learning theory, in other words learning is a social activity and this is based on our needs as humans to fit in with others. In organisations this happens to some extent naturally as we learn to fit in with things such as dress codes, behaviour in meetings and so on. Fitting in means that we can be accepted as successful in the organisation, but it is not necessary that we internalise and believe in these codes. Organisations often use role models, mentors and peer support, and ‘buddies’, to intensify our natural will to fit in. The disadvantages of this perspective are that it ignores the role of choice for the individual and it is based, to some extent, on a masquerade.

The constructivist perspective is a development of the information-processing perspective, but does not regard learning as a neutral process: it is our perception of our experiences that count; there is no ‘objective’ view. This perspective accepts that in our dealings with the world we create ‘meaning structures’ in our heads and these are based on our past experiences and personality. New information and potential learning need to fit with these meaning structures in some way, which means that a similar new experience will be understood differently by different people. We tend to pay attention to things which fit with our meaning structures and ignore or avoid things that don’t fit. As humans we are also capable of constructing and reconstructing our meaning structures without any new experiences. These meaning structures are mainly unconscious and therefore we are not aware of the structures which constrain our learning. We are generally unaware of how valid our meanings sets are, and they are deeply held and difficult to change. Making these structures explicit enables us to challenge them and to start to change them. This perspective recognises that learning is a very personal and potentially threatening process. We develop mechanisms to protect ourselves from this threat, and thus protect ourselves from learning. The implication of this is that learning support needs to encourage introspection and reflection, and providing the perspectives of others (for example as in 360-degree feedback, outdoor courses or relocations) may assist in this process.

2. PRACTICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF LEARNING AND DEVELOPMENT

2.1. Learning from experience

A significant amount of work has been done which helps us understand how managers, and others, learn from their experiences. Kolb et al. (1984) argue that it is useful to combine the characteristics of learning, which is usually regarded as passive, with those of problem solving, which is usually regarded as active. From this combination Kolb et al. developed a four-stage learning cycle, which was further developed by Honey and Mumford (1989).

The four stages, based on the work of both groups of researchers, are shown in Figure 18.1.

Each of these four stages of the learning cycle is critical to effective learning, but few people are strong at each stage and it is helpful to understand where our strengths and weaknesses lie. Honey and Mumford designed a questionnaire to achieve this which identified individuals’ learning styles as ‘activist’, ‘reflector’, ‘theorist’ and ‘pragmatist’, and explain that:

- Activists learn best from ‘having a go’, and trying something out without necessarily preparing. They would be enthusiastic about role-play exercises and keen to take risks in the real environment.

- Reflectors are much better at listening and observing. They are effective at reflecting on their own and others’ experiences and good at analysing what happened and why.

- Theorists’ strengths are in building a concept or a theory on the basis of their analysis. They are good at integrating different pieces of information, and building models of the way things operate. They may choose to start their learning by reading around a topic.

- Pragmatists are keen to use whatever they learn and will always work out how they can apply it in a real situation. They will plan how to put it into practice. They will value information/ideas they are given only if they can see how to relate them to practical tasks they need to do.

Understanding how individuals learn from experience underpins all learning, but is particularly relevant in encouraging self-development activities. Understanding our strengths and weaknesses enables us to choose learning activities which suit our style, and gives us the opportunity to decide to strengthen a particularly weak learning stage of our learning cycle. While Honey and Mumford adopt this dual approach, Kolb firmly maintains that learners must become deeply competent at all stages of the cycle. There has been considerable attention to the issue of matching and mismatching styles with development activities: see, for example, Hayes and Allinson (1996), who also consider the matching and mismatching of trainer learning style with learner learning style.

2.2. Planned and emergent learning

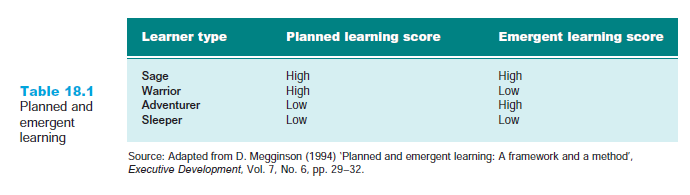

From a different, but compatible, perspective, David Megginson characterises learners by the extent to which they plan the direction of their learning and implement this (planned learning), and the extent to which they are able to learn from opportunistic learning experiences (emergent learning). Megginson (1994) suggests that strengths and weaknesses in these two areas will influence the way individuals react to self-development. These two characteristics are not mutually exclusive, and Megginson combines them to identify four learning types, as shown in Table 18.1.

Warriors are those who are strong at planning what they want to learn and how, but are less strong at learning from experiences they had not ancticipated. They have a clear focus on what they want to learn and pursue this persistently. On the other hand Adventurers respond to and learn from opportunities that come along unexpectedly, they are curious and flexible. However, they tend not to plan and create opportunities for themselves. Sages are strong on both characteristics, and Sleepers display little of either characteristic at present. To be most effective in self-development activities learners need to make maximum use of both planned and emergent learning. For a further explanation of this model also see Megginson and Whitaker (1996).

2.3. Learning curves

The idea of the learning curve has been promulgated for some time, and was developed in relation to technical skills development. The general idea was that we tend to learn a new task more rapidly at first, so that the learning curve is steep, and then gradually plateau after we have had significant experience. A slightly different shape of learning is more relevant to personal skills development: the curve is less likely to be smooth, or it may not even be curved. Ideally our learning would be incremental, improving bit by bit all the time; in reality, however, learning is usually characterised by a mix of improvements and setbacks. Although, with persistence, our skills gradually increase, in the short term we may experience dips. These dips are demotivating but they are a necessary part of learning. Developing personal skills usually requires us to try out a new way of doing things. This is risky because, although the skills we are developing may be quite personal to us, we usually have to experiment with new ways of doing things in public. Understanding that sometimes things get worse before they get better helps to carry us through the dips. Figure 18.2 shows the reality of learning progress.

2.4. Identifying learning and training needs

The ‘systematic training cycle’ was developed to help organisations move away from ad hoc non-evaluated training, and replace it with an orderly sequence of training activities, but this approach has been less prominent of late. Harrison (2005) contests that such a cycle is not necessarily the most appropriate to use as it falls far short of the messy world of practice, and does not focus adequately on learning. Sloman (2001) argues that it may have fitted the 1960s mood for rationality and efficiency, but it is somewhat mechanical and fits less well with our faster pace of continuous change. In spite of this the cycle does retain some value, and we describe an adaptation of such a model to make it more applicable to today’s environment. The model is set within an external environment and within an organisation strategy and an HR development strategy. Even if some of these elements are not made explicit, they will exist implicitly. Note that the boundary lines are dotted, not continuous. This indicates that the boundaries are permeable and overlapping. The internal part of the model reflects a systematic approach to learning and to training. Learning needs may be identified by the individual, by the organisation or in partnership, and this applies to each of the following steps in the circle. This dual involvement is probably the biggest change from traditional models where the steps were owned by the organisation, usually the trainers, and the individual was considered to be the subject of the exercise rather than a participant in it, or the owner of it. The model that we offer does not exclude this approach where appropriate, but is intended to be viewed in a more flexible way. The model is shown in Figure 18.3.

There are various approaches to analysing needs, the two most traditional being a problem-centred approach and matching the individual’s competency profile with that for the job that person is filling. The problem-centred approach focuses on any performance problems or difficulties, and explores whether these are due to a lack of skills and, if so, which. The profile comparison approach takes a much broader view and is perhaps most useful when an individual, or group of individuals, are new to a job. This latter approach is also useful because strategic priorities change and new skills are required of employees, as the nature of their job changes, even though they are still officially in the same role with the same job title. When a gap has been identified, by whatever method, the development required needs to be phrased in terms of a learning objective, before the next stage of the cycle, planning and designing the development, can be undertaken. For example, when a gap or need has been identified around team leadership, appropriate learning objectives may be that learners, by the end of the development, will be able ‘to ask appropriate questions at the outset of a team activity to ascertain relevant skills and experience, and to check understanding of the task’ or ‘to review a team activity by involving all members in that review’.

The planning and design of learning will be influenced by the learning objectives and also by the HR development strategy, which for example may contain a vision of who should be involved in training and development activities, and the emphasis on approaches such as self-development and e-learning. Once planning and design have been specified the course, or coaching or e-learning activity, can commence, and should be subject to ongoing monitoring and evaluated at an appropriate time in the future to assess how behaviour and performance have changed.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

I’ve read several good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how a lot effort you place to create such a great informative web site.

I want reading and I conceive this website got some really useful stuff on it! .