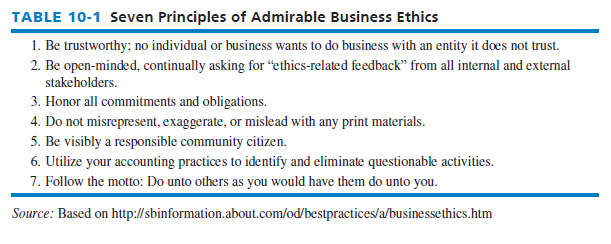

The Institute of Business Ethics (IBE) recently did a study titled “Does Business Ethics Pay?” and concluded that companies displaying a “clear commitment to ethical conduct” consistently outperform companies that do not display ethical conduct. Philippa Foster Black of the IBE stated, “Not only is ethical behavior in business life the right thing to do in principle, it pays off in financial returns.” Alan Simpson remarked, “If you have integrity, nothing else matters. If you don’t have integrity, nothing else matters.” Good ethics is good business. Bad ethics can derail even the best strategic plans. This chapter provides an overview of the importance of business ethics in strategic management. Table 10-1 provides some results of the IBE study.

1. Does It Pay to Be Ethical?

A rising tide of consciousness about the importance of business ethics is sweeping the United States and the rest of the world. Strategists such as CEOs and business owners are the individuals primarily responsible for ensuring that high ethical principles are espoused and practiced in an organization. All strategy formulation, implementation, and evaluation decisions have ethical ramifications.

As indicated in Academic Research Capsule 10-1, it does pay to be ethical; high-performing companies generally exhibit high business ethics. Investor’s Business Daily reported on 7-20-15 (p. A4) that character-driven leaders deliver five times greater profitability results and 26 percent higher workforce engagement than self-focused leaders. Those were the results of a seven-year study by Fred Kiel, author of “Return on Character,” who followed 8,000 employees and 84 top executives of Fortune 500 companies.

Daily, newspapers and business magazines report legal and moral breaches of ethical conduct by both public and private organizations. Being unethical can be expensive. For example, Cisco Systems in 2015 sued Arista Networks for copying verbatim sections of its user manuals. In addition to plagiarism, literally hundreds of business actions are unethical, including:

- Misleading advertising or labeling

- Causing environmental harm

- Poor product or service safety

- Padding expense accounts

- Insider trading

- Dumping banned or flawed products in foreign markets

- Not providing equal opportunities for women and minorities

- Overpricing

- Sexual harassment

- Using company funds or resources for personal gain

Increasingly, executives’ and managers’ personal and professional decisions are placing them in the crosshairs of angry shareholders, disgruntled employees, and even their own boards of directors—making the imperious CEO far more vulnerable to personal, public, and corporate missteps than ever before. “certainly, anybody who is doing something that can be construed as unethical, immoral or greedy is being taken to task,” says paul Dorf of compensation Resources, a consultant to boards of directors.1

Social media and business-centric websites such as glassdoor.com and vault.com as well as disclosure mandates required under Sarbanes-oxley are just several among hundreds of outlets that today quickly spread fact and rumor about the inside dealings of corporations and organizations, revealing ethical breaches and internal business practices that may never have surfaced years ago. Wendy patrick, who teaches business ethics at San Diego State University, states, “God forbid anyone who isn’t squeaky-clean these days or misrepresents their credentials. Anything embarrassing and you begin to question everything. If you aren’t making good decisions in your personal life, it can bleed over to your career (professional life).”

2. What Can We Learn from High-Performance Companies?

Research at DePaul University in Chicago by Frigo and Litman found a pattern of strategic activities of high-performance companies. Their research involved screening the financial performance of more than 15,000 public companies using 30 years of financial data and identifying about 100 high-performance companies. Here are three lessons from high-performance companies studied:

- Commitment to Return on Investment and Ethical Business Conduct: High-performance companies demonstrate a strong commitment to creating shareholder value by focusing on sustainable return on investment (ROI). These companies achieve superior ROI and growth while adhering to ethical business conduct, such as Johnson & Johnson, which is famous for its credo as a foundation for ethical business conduct at the company.

- Focus on Unmet Customer Needs in Growing Market Segments: To avoid commoditization, high-performance companies concentrate on fulfilling unmet customer needs and target growing market segments. Harley-Davidson targets customer needs (lifestyle, freedom, community) with their unique Harley experience while pursuing a growing customer group (the Baby Boom generation).

- Innovate Offerings: High-performance companies constantly reexamine their products and services (their offerings), modifying existing ones and developing new ones that will better fulfill customers’ unmet needs. For example, Apple demonstrate this characteristic through its innovation strategy.

Source: Based on Mark L. Frigo and Joel Litman, DRIVEN: Business Strategy, Human Actions and the Creation of Wealth, Strategy and Execution (Chicago: Strategy & Execution LLC, 2008).

3. Who Is Prone to Be Unethical in a Business?

Prior research suggests that being unethical is abnormal, rare, and most often perpetrated by people who are abhorrent. However, Donald Palmer recently reported that misconduct is a normal phenomenon and that wrongdoing is as prevalent as “rightdoing,” and that misconduct is most often done by people who are primarily good, ethical, and socially responsible. Palmer reports that individuals engage in unethical activities due to a plethora of structure, processes, and mechanisms inherent in the functioning of organizations—and, importantly, all of us are candidates to be unethical under the right circumstances in any organization. Implications of this new research abound for managers. In light of his findings, Palmer concludes that organizations should implement the following six procedures as soon as possible:

- Punish wrongdoing swiftly and severely when it is detected.

- Be careful to hire employees who possess high ethical standards.

- Develop socialization programs to reinforce desired cultural values.

- Alter chains of command so subordinates report to more than one superior.

- Develop a culture whereby subordinates may challenge their superior’s orders when they seem questionable.

- Develop a better understanding of internal policies, procedures, systems, and mechanisms that could lead to misconduct.

Source: Based on Donald Palmer, “The New Perspective on Organizational Wrongdoing,” California Management Review, 56, no. 1 (2013): 5-23.

4. How to Establish an Ethics Culture

A new wave of ethics issues has recently surfaced related to product safety, employee health, sexual harassment, AIDS in the workplace, smoking, acid rain, affirmative action, waste disposal, foreign business practices, cover-ups, takeover tactics, conflicts of interest, employee privacy, inappropriate gifts, and security of company records. A key ingredient for establishing an ethics culture is to develop a clear code of business ethics. Internet fraud, hacking into company computers, spreading viruses, and identity theft are other unethical activities that plague every sector of online commerce.

As indicated in Academic Research Capsule 10-2, anyone is prone to be unethical in a business, so Donald palmer provides six procedures to establish an ethics culture.

Merely having a code of ethics, however, is not sufficient to ensure ethical business behavior. A code of ethics can be viewed as a public relations gimmick, a set of platitudes, or window dressing. To ensure that the code is read, understood, believed, and remembered, periodic ethics workshops are needed to sensitize people to workplace circumstances in which ethics issues may arise.2 If employees see examples of punishment for violating the code as well as rewards for upholding the code, this reinforces the importance of a firm’s code of ethics. The website www.ethicsweb.ca/codes provides guidelines on how to write an effective code of ethics.

Reverend Billy Graham once said, “When wealth is lost, nothing is lost; when health is lost, something is lost; when character is lost, all is lost.” An ethics “culture” needs to permeate organizations! To help create an ethics culture, Citicorp developed a business ethics board game that is played by thousands of employees worldwide. called “The Word Ethic,” this game asks players business ethics questions, such as “How do you deal with a customer who offers you football tickets in exchange for a new, backdated IRA?” Diana Robertson at the Wharton School of Business believes the game is effective because it is interactive. Many organizations have developed a code-of-conduct manual outlining ethical expectations and giving examples of situations that commonly arise in their businesses.

One reason strategists’ salaries are high is that they must take the moral risks of the firm. Strategists are responsible for developing, communicating, and enforcing the code of business ethics for their organizations. Although primary responsibility for ensuring ethical behavior rests with a firm’s strategists, an integral part of the responsibility of all managers is to provide ethics leadership by constant example and demonstration. Managers hold positions that enable them to influence and educate many people. This makes managers responsible for developing and implementing ethical decision making. Gellerman and Drucker, respectively, offer some good advice for managers:

All managers risk giving too much because of what their companies demand from them. But the same superiors who keep pressing you to do more, or to do it better, or faster, or less expensively, will turn on you should you cross that fuzzy line between right and wrong. They will blame you for exceeding instructions or for ignoring their warnings. The smartest managers already know that the best answer to the question “How far is too far?” is don’t try to find out.3

A man (or woman) might know too little, perform poorly, lack judgment and ability, and yet not do too much damage as a manager. But if that person lacks character and integrity—no matter how knowledgeable, how brilliant, how successful—he destroys. He destroys people, the most valuable resource of the enterprise. He destroys spirit. And he destroys performance. This is particularly true of the people at the head of an enterprise because the spirit of an organization is created from the top. If an organization is great in spirit, it is because the spirit of its top people is great. If it decays, it does so because the top rots. As the proverb has it, “Trees die from the top.” No one should ever become a strategist unless he or she is willing to have his or her character serve as the model for subordinates.4

No society anywhere in the world can compete long or successfully with people stealing from one another or not trusting one another, with every bit of information requiring notarized confirmation, with every disagreement ending up in litigation, or with government having to regulate businesses to keep them honest. Being unethical is a recipe for headaches, inefficiency, and waste. History has proven that the greater the trust and confidence of people in the ethics of an institution or society, the greater its economic strength. Business relationships are built mostly on mutual trust and reputation. Short-term decisions based on greed and questionable ethics will preclude the necessary self-respect to gain the trust of others. More and more firms believe that ethics training and an ethics culture create strategic advantage. According to Max Killan, “If business is not based on ethical grounds, it is of no benefit to society, and will, like all other unethical combinations, pass into oblivion.”

Source: David Fred, David Forest (2016), Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach, Concepts and Cases, Pearson (16th Edition).

17 May 2021

18 May 2021

18 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021

17 May 2021