Market segmentation divides a market into well-defined slices. A market segment consists of a group of customers who share a similar set of needs and wants. The marketer’s task is to identify the appropriate number and nature of market segments and decide which one(s) to target.

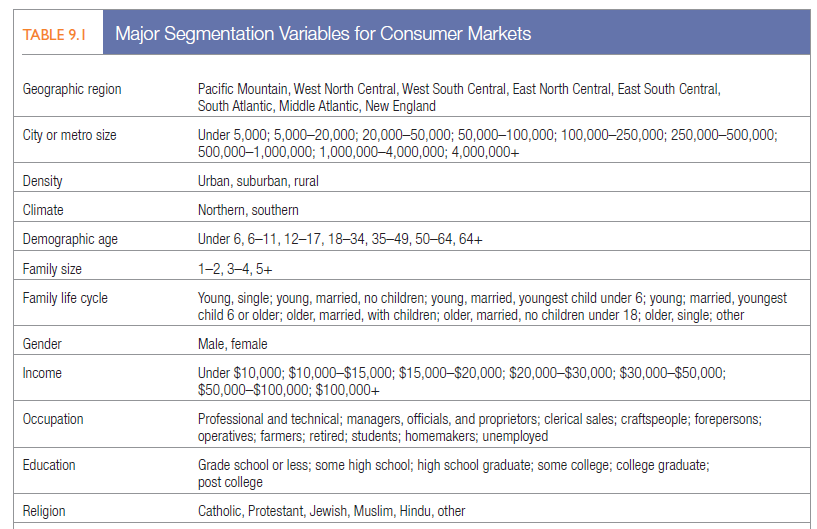

We use two broad groups of variables to segment consumer markets. Some researchers define segments by looking at descriptive characteristics—geographic, demographic, and psychographic—and asking whether these segments exhibit different needs or product responses. For example, they might examine the differing attitudes of “professionals” “blue collars” and other groups toward, say, “safety” as a product benefit.

Other researchers define segments by looking at behavioral considerations, such as consumer responses to benefits, usage occasions, or brands, then seeing whether different characteristics are associated with each consumer- response segment. For example, do people who want “quality” rather than “low price” in an automobile differ in their geographic, demographic, and/or psychographic makeup?

Regardless of which type of segmentation scheme we use, the key is adjusting the marketing program to recognize customer differences. The major segmentation variables—geographic, demographic, psychographic, and behavioral segmentation—are summarized in Table 9.1.

1. GEOGRAPHIC SEGMENTATION

Geographic segmentation divides the market into geographical units such as nations, states, regions, counties, cities, or neighborhoods. The company can operate in one or a few areas, or it can operate in all but pay attention to local variations. In that way it can tailor marketing programs to the needs and wants of local customer groups in trading areas, neighborhoods, even individual stores. In a growing trend called grassroots marketing, marketers concentrate on making such activities as personally relevant to individual customers as possible.

Much of Nike’s initial success came from engaging target consumers through grassroots marketing efforts such as sponsorship of local school teams, expert- conducted clinics, and provision of shoes, clothing, and equipment to young athletes. Citibank provides different mixes of banking services in its branches depending on neighborhood demographics. Retail firms such as Starbucks, Costco, Trader Joe’s, and REI have all found great success emphasizing local marketing initiatives, and other types of firms have also jumped into the action.2

More and more, regional marketing means marketing right down to a specific zip code. Many companies use mapping software to pinpoint the geographic locations of their customers, learning, say, that most customers are within a 10-mile radius of the store and are further concentrated within certain zip+4 areas. By mapping the densest areas, the retailer can rely on customer cloning, assuming the best prospects live where most of the customers already come from.

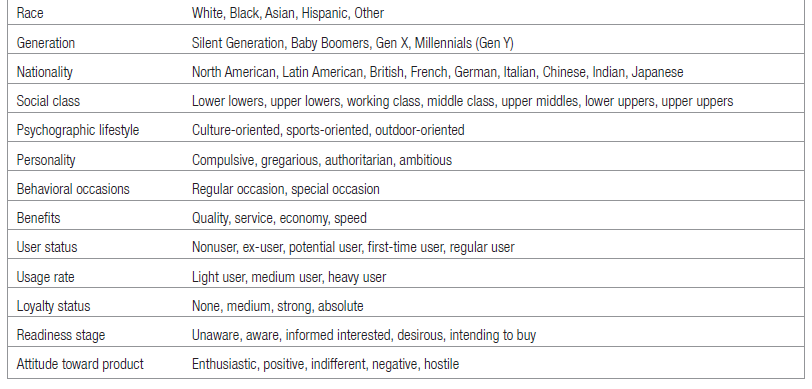

Some approaches combine geographic data with demographic data to yield even richer descriptions of consumers and neighborhoods. Nielsen Claritas has developed a geoclustering approach called PRIZM (Potential Rating Index by Zip Markets) NE that classifies more than half a million U.S. residential neighborhoods into 14 distinct groups and 66 distinct lifestyle segments called PRIZM Clusters.3 The groupings take into consideration 39 factors in five broad categories: (1) education and affluence, (2) family life cycle, (3) urbanization, (4) race and ethnicity, and (5) mobility. The neighborhoods are broken down by zip code, zip+4, or census tract and block group. The clusters have descriptive titles such as Blue Blood Estates, Winner’s Circle, Hometown Retired, Shotguns and Pickups, and Back Country Folks. The inhabitants in a cluster tend to lead similar lives, drive similar cars, have similar jobs, and read similar magazines. Table 9.2 has examples of three PRIZM clusters.

Geoclustering captures the increasing diversity of the U.S. population. PRIZM has been used to answer questions such as: Which neighborhoods or zip codes contain our most valuable customers? How deeply have we already penetrated these segments? Which distribution channels and promotional media work best in reaching our target clusters in each area? Barnes & Nobles placed its stores where the “Money & Brains” segment hangs out. Hyundai successfully targeted a promotional campaign to neighborhoods where the “Kids & Cul-de-Sacs,” “Bohemian Mix,” and “Pool & Patios” could be found.4

Marketing to microsegments has become possible even for small organizations as database costs decline, software becomes easier to use, and data integration increases. Going online to reach customers directly can open a host of local opportunities, as Yelp has found out.5

YELP Founded in 2004, Yelp.com wants to “connect people with great local businesses” by targeting consumers who seek or want to share reviews of local businesses in 96 markets around the world. Almost two-thirds of the Web site’s millions of vetted online reviews are for restaurants and retailers. Yelp was launched in San Francisco, where monthly parties with preferred users evolved into a formal program, Yelp Elite, now used to launch the service into new cities. The company’s recently introduced mobile app allows it to bypass the Internet and connect with consumers directly; almost 50 percent of searches on the site now come from its mobile platform. Yelp generates revenue by selling designated Yelp Ads to local merchants via hundreds of salespeople. The local advertising business is massive—estimated to be worth between $90 billion and $130 billion—but relatively untapped given that many local businesses are not that tech-savvy. Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook (a Yelp competitor), calls local advertising the Internet’s “Holy Grail.” Local businesses also benefit from Yelp—several research studies have demonstrated the potential revenue payback from having reviews of their businesses on the site.

Those who favor such localized marketing see national advertising as wasteful because it is too “arm’s length” and fails to address local needs. Those against local marketing argue that it drives up manufacturing and marketing costs by reducing economies of scale and magnifying logistical problems. A brand’s overall image might be diluted if the product and message are too different in different localities.

2. DEMOGRAPHIC SEGMENTATION

One reason demographic variables such as age, family size, family life cycle, gender, income, occupation, education, religion, race, generation, nationality, and social class are so popular with marketers is that they’re often associated with consumer needs and wants. Another is that they’re easy to measure. Even when we describe the target market in nondemographic terms (say, by personality type), we may need the link back to demographic characteristics in order to estimate the size of the market and the media we should use to reach it efficiently.

Here’s how marketers have used certain demographic variables to segment markets.

AGE AND LIFE-CYCLE STAGE Consumer wants and abilities change with age. Toothpaste brands such as Crest and Colgate offer three main lines of products to target kids, adults, and older consumers. Age segmentation can be even more refined. Pampers divides its market into prenatal, new baby (0-5 months), baby (6-12 months), toddler (13-23 months), and preschooler (24 months+). Indirect age effects also operate for some products. One study of kids ages 8-12 found that 91 percent decided or influenced clothing or apparel buys, 79 percent grocery purchases, and 54 percent vacation choices, while 14 percent even made or swayed vehicle purchase decisions.6

Nevertheless, age and life cycle can be tricky variables. The target market for some products may be the psychologically young. To target 21-year-olds with its boxy Element, which company officials described as a “dorm room on wheels,” Honda ran ads depicting sexy college kids partying near the car at a beach. So many baby boomers were attracted to the ads, however, that the average age of Element buyers turned out to be 42! With baby boomers seeking to stay young, Honda decided the lines between age groups were getting blurred. When sales fizzled, Honda decided to discontinue sales of the Element. When it was ready to launch a new subcompact called the Fit, the firm deliberately targeted Gen Y buyers as well as their empty-nest parents.7

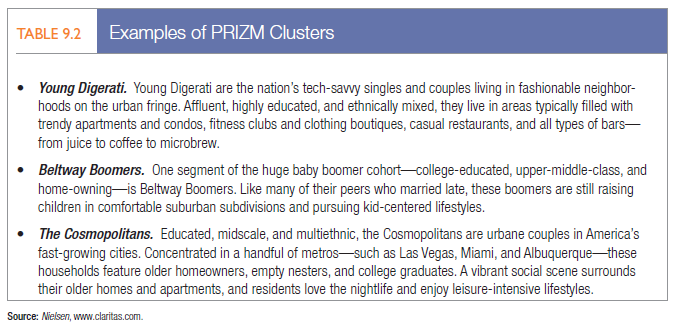

LIFE STAGE People in the same part of the life cycle may still differ in their life stage. Life stage defines a person’s major concern, such as going through a divorce, going into a second marriage, taking care of an older parent, deciding to cohabit with another person, buying a new home, and so on. As Chapter 6 noted, these life stages present opportunities for marketers who can help people cope with the accompanying decisions.

For example, the wedding industry attracts marketers of a vast range of products and services. No surprise—the average U.S. couple spends almost $27,000 on their wedding (see Table 9.3 for some major wedding expenditures).8 But that’s just the start. Newlyweds in the United States spend a total of about $70 billion on their households in the first year after marriage—and they buy more in the first six months than an established household does in five years!

Marketers know marriage often means two sets of shopping habits and brand preferences must be blended into one. Procter & Gamble, Clorox, and Colgate-Palmolive include their products in “Newlywed Kits,” distributed when couples apply for a marriage license. JCPenney has identified “Starting Outs” as one of its two major customer groups. Marketers pay a premium for name lists to assist their direct marketing because, as one noted, newlywed names “are like gold.”9

But not everyone goes through that life stage at a certain time—or at all, for that matter. More than a quarter of all U.S. households now consist of only one person—a record high. It’s no surprise this $1.9 trillion market is attracting interest from marketers: Lowe’s has run an ad featuring a single woman renovating her bathroom; DeBeers sells a “right-hand ring” for unmarried women; and at the recently opened, ultra-hip Middle of Manhattan 63-floor tower, two-thirds of the occupants live alone in one-bedroom and studio rental apartments.10

GENDER Men and women have different attitudes and behave differently, based partly on genetic makeup and partly on socialization.11 Research shows that women have traditionally tended to be more communal-minded and men more self-expressive and goal-directed; women have tended to take in more of the data in their immediate environment and men to focus on the part of the environment that helps them achieve a goal.

A research study of shopping found that men often need to be invited to touch a product, whereas women are likely to pick it up without prompting. Men often like to read product information; women may relate to a product on a more personal level.

Marketers can now reach women more easily via media like Lifetime, Oxygen, and WE television networks and scores of women’s magazines and Web sites; men are more easily found at ESPN, Comedy Central, and Spike TV channels and through magazines such as Maxim and Men’s Health.12 After Pinterest proved its popularity among women, five different Web sites with similar functionality but targeted at men sprang up, including MANinteresting, Dudepins, and Gentlemint.13

Gender differences are shrinking in some other areas as men and women expand their roles. One Yahoo survey found that more than half of men identified themselves as the primary grocery shoppers in their households. Procter & Gamble now designs some ads with men in mind, such as for its Gain and Tide laundry detergents, Febreze air freshener, and Swiffer sweepers. On the flip side, according to some studies, women in the United States and the United Kingdom make 75 percent of decisions about buying new homes and purchase 60 percent of new cars.14

Nevertheless, gender differentiation has long been applied in clothing, hairstyling, and cosmetics. Avon, for one, has built a $6 billion-plus business by selling beauty products to women. Gillette has found similar success with its Venus razor

VENUS RAZOR Gillette’s Venus razor has become the most successful women’s shaving line ever— holding more than 50 percent of the global women’s shaving market—as a result of insightful consumer research and extensive market tests revealing product design, packaging, and advertising cues. The razor was a marked departure from earlier designs, which had essentially been colored or repackaged versions of men’s razors. Venus was designed to uniquely meet women’s needs, instead of men’s. Extensive research identified unique shaving needs for women, including shaving a surface area 9X greater than the male face; in a wet environment and across the unique curves of the body. The resulting female design included an oval shaped cartridge to better fit in to tight areas like underarms and bikini and additional lubrication for better glide. Furthermore, after discovering that women change their grip on a razor about 30 times during each shaving session, Gillette designed Venus razor with a wide, sculpted rubberized handle offering superior grip and control. Design work did not stop with the differences between men and women’s shaving needs, when Gillette later found four distinct segments of female shavers—perfect shave seekers (no missed hairs), skin pamperers, pragmatic functionalists, and EZ seekers—the company designed Venus products for each of them. It also commissioned Harris Interactive to conduct an online study among more than 6,500 women in 13 countries that found seven of 10 wanted so-called goddess skin, defined as smooth (68 percent), healthy (66 percent), and soft (61 percent), leading to the introduction of the new Gillette Venus & Olay razor.

INCOME Income segmentation is a long-standing practice in such categories as automobiles, clothing, cosmetics, financial services, and travel. However, income does not always predict the best customers for a given product. Blue-collar workers were among the first purchasers of color television sets; it was cheaper for them to buy a television than to go to movies and restaurants.

Many marketers are deliberately going after lower- income groups, in some cases discovering fewer competitive pressures or greater consumer loyalty. Procter & Gamble launched two discount-priced brand extensions in 2005—Bounty Basic and Charmin Basic— which have met with some success. Other marketers are finding success with premium-priced products. When Whirlpool launched a pricey Duet washer line, sales doubled their forecasts in a weak economy, due primarily to middle-class shoppers who traded up.

Increasingly, companies are finding their markets are hourglass-shaped, as middle-market U.S. consumers migrate toward both discount and premium products. Companies that miss out on this new market risk being “trapped in the middle” and seeing their market share steadily decline. Recognizing that its channel strategy emphasized retailers like Sears selling primarily to the middle class, Levi-Strauss has since introduced premium lines such as Levi’s Made & Crafted to upscale retailers Bloomingdales and Saks Fifth Avenue and the less-expensive Signature by Levi Strauss & Co. line to mass-market retailers Walmart and Kmart.

GENERATION Each generation or cohort is profoundly influenced by the times in which it grows up—the music, movies, politics, and defining events of that period. Members share the same major cultural, political, and economic experiences and often have similar outlooks and values. Marketers may choose to advertise to a cohort by using the icons and images prominent in its experiences. They can also try to develop products and services that uniquely meet the particular interests or needs of a generational target.

Although the beginning and ending birth dates of any generation are always subjective—and generalizations can mask important differences within the group—here are some general observations about the four main generation cohorts of U.S. consumers, from youngest to oldest.16

Millennials (or Gen Y) Although different age splits are used to define Millennials, or Gen Y, the term usually means people born between 1977 and 1994. That’s about 78 million people in the United States, with annual spending power approaching $200 billion. If you factor in career growth and household and family formation and multiply by another 53 years of life expectancy, trillions of dollars in consumer spending are at stake over their life spans. It’s not surprising that marketers are racing to get a bead on Millennials’ buying behavior. Here is how one bank has targeted these consumers.17

PNC’S VIRTUAL WALLET In early 2007, PNC Bank hired design consultants IDEO to study Gen Y—defined by PNC at that time as 18- to 34-year-olds—to help develop a marketing plan to appeal to them. IDEO’s research found this cohort (1) didn’t know how to manage money and (2) found bank Web sites clunky and awkward to use. PNC thus chose to introduce a new offering, Virtual Wallet, that combined three accounts—“Spend” (regular checking and bill payments), “Reserve” (backup interest-bearing checking for overdraft protection and emergencies), and “Grow” (long-term savings)—with a slick personal finance tool—the “Money Bar”—by which customers can drag money from account to account online by adjusting an on-screen slider. Instead of seeing a traditional ledger, customers can view balances on a calendar that displays estimated future cash flow based on when they get paid, when they pay their bills, and what their spending habits are. Customers also can set a “Savings Engine” tool to transfer money to savings when they receive a paycheck as well as get their account balances via text. PNC has added even more features to Virtual Wallet, such as transaction information for credit cards and a joint calendar view for joint account holders, which has expanded the service’s appeal beyond its 1 million Gen Y customers. PNC also engages 80,000-plus of its Virtual Wallet customers in an “Inside the Wallet” blog, which the bank feels provides more detailed feedback than it can get with its Twitter and Facebook accounts.

Also known as the Echo Boomers, “digital native” Millennials have been wired almost from birth—playing computer games, navigating the Internet, downloading music, and connecting with friends via texting and social

media. They are much more likely than other age groups to own multiple devices and multitask while online, moving across mobile, social, and PC platforms. They are also more likely to go online to broadcast their thoughts and experiences and to contribute user-generated content. They tend to trust friends more than corporate sources of information.18

Although they may have a sense of entitlement and abundance from growing up during the economic boom and being pampered by their boomer parents, Millennials are also often highly socially conscious, concerned about environmental issues, and receptive to cause marketing efforts. The recession hit them hard, and many have accumulated sizable debt. One implication is they are less likely to have bought their first homes and more likely to still live with their parents, influencing their purchases in what demographers are calling a “boom-boom” or boomerang effect. That is, the same products that appeal to 20-somethings also appeal to many of their youth- obsessed parents.

Because Gen Y members are often turned off by overt branding practices and “hard sell,” marketers have tried many different approaches to reach and persuade them.19 Consider these widely used experiential tactics.

- Student ambassadors—Red Bull enlisted college students as Red Bull Student Brand Managers to distribute samples, research drinking trends, design on-campus marketing initiatives, and write stories for student newspapers. American Eagle, among other brands, has also developed an extensive campus ambassador program.

- Street teams—Long a mainstay in the music business, street teams help to promote bands both big and small. Rock band Foo Fighters created a digital street team that sends targeted e-mail blasts to members who “get the latest news, exclusive audio/video sneak previews, tons of chances to win great Foo Fighters prizes, and become part of the Foo Fighters Family.”

- Cool events—Hurley, which defined itself as an authentic “Microphone for Youth” brand rooted in surf, skate, art, music, and beach cultures, has been a long-time sponsor of the U.S. Open of Surfing. The actual title sponsor for the 2013 event was Vans, whose shoes and clothing also have strong Millennial appeal. Vans has also been the title sponsor for almost 20 years of the Warped tour, which blends music with action (or extreme) sports.

Gen X Often lost in the demographic shuffle, the 50 million or so Gen X consumers, named for a 1991 novel by Douglas Coupland, were born between 1964 and 1978. The popularity of Kurt Cobain, rock band Nirvana, and the lifestyle portrayed in the critically lauded film Slacker led to the use of terms like grunge and slacker to characterize Gen X when they were teens and young adults. They bore an unflattering image of disaffection, short attention spans, and weak work ethic.

These stereotypes have slowly disappeared. Gen Xers were certainly raised in more challenging times, when working parents relied on day care or left “latchkey kids” on their own after school and corporate downsizing led to the threat of layoffs and economic uncertainty. At the same time, social and racial diversity were more widely accepted, and technology changed the way people lived and worked. Although Gen Xers raised standards in educational achievement, they were also the first generation to find surpassing their parents’ standard of living a serious challenge.

These realities had a profound impact. Gen Xers prize self-sufficiency and the ability to handle any circumstance. Technology is an enabler for them, not a barrier. Unlike the more optimistic, team-oriented Gen Yers, Gen Xers are more pragmatic and individualistic. As consumers, they are wary of hype and pitches that seem inauthentic or patronizing. Direct appeals where value is clear often work best, especially as Gen Xers have become parents raising families.20

Baby Boomers Baby boomers are the approximately 76 million U.S. consumers born between 1946 and 1964. Though they represent a wealthy target, possessing $1.2 trillion in annual spending power and controlling three- quarters of the country’s wealth, marketers often overlook them. In network television circles, because advertisers are primarily interested in 18- to 49-year-olds, viewers over 50 are referred to as “undesirables,” though ironically the average age of the prime-time TV viewer is 51.

With many baby boomers approaching their 70s and even the last and youngest wave cresting 50, demand has exploded for products to turn back the hands of time. According to one survey, nearly one in five boomers was actively resisting the aging process, driven by the mantra “Fifty is the new thirty.” As they search for the fountain of youth, sales of hair replacement and hair coloring aids, health club memberships, home gym equipment, skintightening creams, nutritional supplements, and organic foods have all soared.

Contrary to conventional marketing wisdom that brand preferences of consumers over 50 are fixed, one study of boomers ages 55 to 64 found a significant number are willing to change brands, spend on technology, use social networking sites, and purchase online.21 Although they love to buy things, they hate being sold to, and as one marketer noted, “You have to earn your stripes every day.” But abundant opportunity exists. Boomers are also less likely to associate retirement with “the beginning of the end” and see it instead as a new chapter in their lives with new activities, interests, careers, and even relationships.22

Silent Generation Those born between 1925 and 1945—the “Silent Generation”—are redefining what old age means. To start with, many people whose chronological age puts them in this category don’t see themselves as old.23 One survey found that 60 percent of respondents over 65 said they felt younger than their actual age. A third of those 65 to 74 said they felt 10 to 19 years younger, and one in six felt at least 20 years younger than their actual age.24

Consistent with what they say, many older consumers lead very active lives. As one expert noted, it is if they were having a second middle age before becoming elderly. Advertisers have learned that older consumers don’t mind seeing other older consumers in ads targeting them, as long as they appear to be leading vibrant lives. But marketers have learned to avoid cliches like happy older couples riding bikes or strolling hand in hand on a beach at sunset.

Strategies emphasizing seniors’ roles as grandparents are well received. Many older consumers not only happily spend time with their grandkids, they often provide for their basic needs and at least occasional gifts. The founders of eBeanstalk.com, which sells children’s learning toys, thought their online business would be driven largely by young consumers starting families. They were surprised to find that as much as 40 percent of their customers were older, mainly grandparents. These customers are very demanding but also more willing to pay full price than their younger counterparts.25

But they also need their own products. To design better appliances for the elderly, GE holds empathy sessions to help designers understand the challenges of aging. They tape their knuckles to represent arthritic hands, put kernels of popcorn in their shoes to create imbalance, and weigh down pans to simulate the challenge of putting food into ovens. Researchers at the MIT AgeLab use a suit called AGNES (Age Gain Now Empathy System) to research the changing needs of the elderly. The suit has a pelvic harness that connects to a headpiece, mimicking an aging spine and restricted mobility, range of motion, joint function, balance, and vision.26

Race and Culture Multicultural marketing is an approach recognizing that different ethnic and cultural segments have sufficiently different needs and wants to require targeted marketing activities and that a mass market approach is not refined enough for the diversity of the marketplace. Consider that McDonald’s now does 40 percent of its U.S. business with ethnic minorities. Its highly successful “I’m Lovin’ It” campaign was rooted in hip-hop culture but has had an appeal that transcended race and ethnicity.27

The Hispanic American, African American, and Asian American markets are all growing at two to three times the rate of nonmulticultural populations, with numerous submarkets, and their buying power is expanding. Multicultural consumers also vary in whether they are first, second, or a later generation and whether they are immigrants or born and raised in the United States.

Marketers need to factor the norms, language nuances, buying habits, and business practices of multicultural markets into the initial formulation of their marketing strategy, rather than adding these as an afterthought. All this diversity also has implications for marketing research; it takes careful sampling to adequately profile target markets.

Multicultural marketing can require different marketing messages, media, channels, and so on. Specialized media exist to reach virtually any cultural segment or minority group, though some companies have struggled to provide financial and management support for fully realized programs.

Fortunately, as countries become more culturally diverse, many marketing campaigns targeting a specific cultural group can spill over and positively influence others. Ford developed a TV ad featuring comedian Kevin Hart to launch its new Explorer model that initially targeted the African American market, but it became one of the key ads for the general market launch too.28

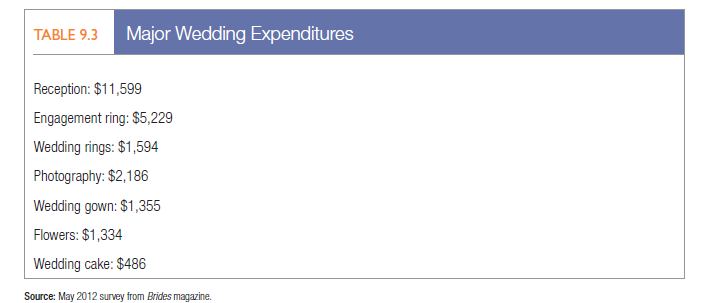

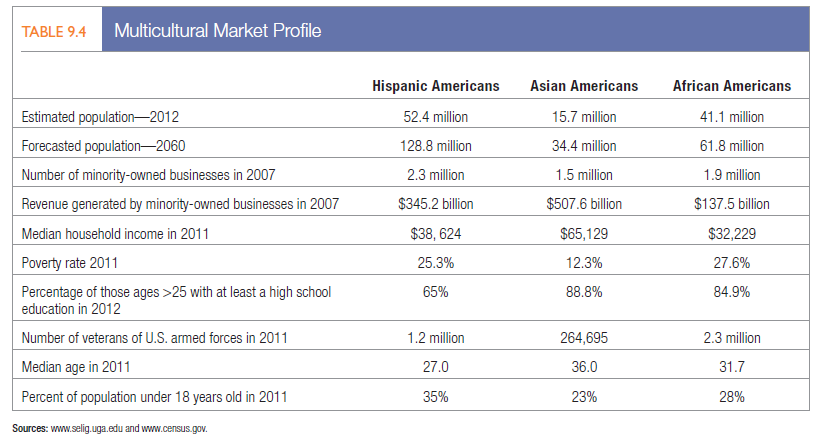

Next, we consider issues in the three largest multicultural markets—Hispanic Americans, African Americans, and Asian Americans. Table 9.4 lists some important facts and figures about them.29

Hispanic Americans Accounting for more than half the growth in the U.S. population from 2000 to 2010, Hispanic Americans have become the largest minority in the country. It’s projected that by 2020, 17 percent of U.S. residents will be of Hispanic origin. With annual purchasing power of more than $1 trillion in 2010—and expected to rise to $1.5 trillion by 2015—Hispanic Americans would be the world’s ninth-largest market if they were a separate nation.

This segment is youthful. The median age of U.S. Hispanics is 27—right in the middle of the highly coveted 18- to-34 Millennial age range—compared with a median age of 42 for non-Hispanic whites. In fact, every 30 seconds, two non-Hispanics retire while a Hispanic turns 18.31 Hispanic Millennials have been called “fusionistas” because they see themselves as both fully American and Latino.32 As one marketing executive noted, “they eat tamales and burgers and watch football and futbol.”33

More than half the U.S. Hispanic population lives in just three states—California, Texas, and Florida—and more than 4 million Hispanics live in New York and Los Angeles. The Hispanic American market holds a wide variety of subsegments. Hispanics of Mexican origin are the dominant segment, followed by those of Puerto Rican and Cuban descent, though numbers of Salvadorans, Dominicans, Guatemalans, and Columbians are growing faster.34

To meet these divergent needs, Goya, the largest U.S. Hispanic food company with $1.3 billion in annual revenue, sells 1,600 products ranging from bags of rice to ready-to-eat, frozen empanadas and 38 varieties of beans alone. The company also has found much success selling key products directly to non-Hispanics. Its new philosophy: “We don’t market to Latinos, we market as Latinos.”35

Hispanic Americans often share strong family values—several generations may reside in one household—and strong ties to their country of origin. Even young Hispanics born in the United States tend to identify with the country their families are from. Hispanic Americans desire respect, are brand loyal, and take a keen interest in product quality. Procter & Gamble’s research revealed that Hispanic consumers believe “lo barato sale caro” (“cheap can be expensive,” or in the English equivalent, “you get what you pay for”). P&G found Hispanic consumers were so value-oriented they would even do their own product tests at home. One woman was using different brands of tissues and toilet paper in different rooms to see which her family liked best.36

U.S.-born Hispanic Americans also have different needs and tastes than their foreign-born counterparts and, though bilingual, often prefer to communicate in English. Though two-thirds of U.S. Hispanics are considered “bicultural” and comfortable with both Spanish- and English-speaking cultures, most firms choose to run Spanish- only ads on traditional Hispanic networks Univision and Telemundo. Univision is the long-time market-leader, which has found great success with its DVR-proof telenovelas (like daily soap operas), though new competition is emerging from Fox and other media companies.37

Marketers are reaching out to Hispanic Americans with targeted promotions, ads, and Web sites, but they need to capture the nuances of cultural and market trends.38 Consider two companies that did so.

- Although Kleenex was the market-share leader in facial tissues among Hispanics, brand owner Kimberly- Clark felt there was much room to grow. Relying on research showing that more than twice as many Hispanics base their purchase decisions on package and design as in the general population, it launched the “Con Kleenex, Expresa Tu Hispanidad” campaign. Amateur artists were solicited to submit designs for customized packages sold during National Hispanic Heritage Month. Public voting chose three winners, and the campaign increased Kleenex sales at participating retailers by an impressive 476 percent.39

- The Clorox Company found its Hispanic American customers were relatively more likely to agree or overindex on “cleaning more to prevent family and friends from getting sick,” especially in spring and summer months and when visitors came. Additional research also revealed the importance of packaging and a preference for scent as the final step in the cleaning process. Product development led to the launch of the FRANGAZIA line of cleaning products with lavender and other scents that had tested well. As support, Spanish-only ads were run on Hispanic media.40

General Motors, Southwestern Airlines, and Toyota have used a “Spanglish” approach in their ads, conversationally mixing some Spanish with English in dialogue among Hispanic families.41 Continental Airlines, General Mills, and Sears have used mobile marketing to reach Hispanics.42 With a mostly younger population that may have less access to Internet or landline service, Hispanics are much more active with mobile technology and social media than the general population. Staying connected to friends and family is important for them.43

Asian Americans According to the U.S. Census Bureau, “Asian” refers to people having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent. Six countries represent 79 percent of the Asian American population: China (21 percent), the Philippines (18 percent), India (11 percent), Vietnam (10 percent), Korea (10 percent), and Japan (9 percent).

The diversity of these national identities limits the effectiveness of pan-Asian marketing appeals. For example, in terms of general food trends, research has uncovered that Japanese eat much more raw food than Chinese; Koreans are more inclined to enjoy spicy foods and drink more alcohol than other Asians; and Filipinos tend to be the most Americanized and Vietnamese the least Americanized in terms of food choices.44

The Asian American market has been called the “invisible market” because, compared with the Hispanic Americans and African American markets, it has traditionally received a disproportionally small fraction of U.S. companies’ total multicultural marketing expenditure.45 Yet it is getting easier to reach this market, given Asian- language newspapers, magazines, cable TV channels, and radio stations targeting specific groups.46

Telecommunications and financial services are a few of the industries more actively targeting Asian Americans. Wells Fargo Bank has a long tradition of marketing to Asian Americans, aided by its deep historical roots in California where a heavy concentration exists. The bank has engaged its Asian American agency partner, Dae Partners, for years. Wells Fargo itself is diverse with an internal team of multicultural experts and a significant group of Asian American executives. It has developed products and programs specifically for the Asian American market and is highly engaged in volunteerism and community efforts.47

Asian Americans tend to be more brand-conscious than other minority groups yet are the least loyal to particular brands. They also tend to care more about what others think (for instance, whether their neighbors will approve of them) and share core values of safety and education. Comparatively affluent and well educated, they are an attractive target for luxury brands. The most computer-literate group, Asian Americans are more likely to use the Internet on a daily basis.48

African Americans African Americans are projected to have a combined spending power of $1.1 trillion by 2015. They have had a significant economic, social, and cultural impact on U.S. life, contributing inventions, art, music, sports achievements, fashion, and literature. Like many cultural segments, they are deeply rooted in the U.S. landscape while also proud of their heritage and respectful of family ties.49

Based on survey findings, African Americans are the most fashion-conscious of all racial and ethnic groups but are strongly motivated by quality and selection. They’re also more likely to be influenced by their children when selecting a product and less likely to buy unfamiliar brands. African Americans watch television and listen to the radio more than other groups and are heavy users of mobile data. Nearly three-fourths have a profile on more than one social network, with Twitter being extremely popular.50

Media outlets directed at black audiences received only 2 percent of the $120 billion firms spent on advertising in 2011, however.51 A Nielsen research study found that roughly half of African Americans say they are more likely to buy a product if its advertising portrays the black community in a positive manner. More than 90 percent said black media are more relevant to them than generic media outlets.52 To encourage more marketing investment, the Cabletelevision Advertising Bureau trade organization even created an information-laden Web site, www.reachingblackconsumers.com.

Ad messages targeting African Americans must be seen as relevant. In a campaign for Lawry’s Seasoned Salt targeting African Americans, images of soul food appeared; a campaign for Kentucky Fried Chicken showed an African American family gathered at a reunion—demonstrating an understanding of both the markets values and its lifestyle.53 P&G’s “My Black Is Beautiful” campaign was started by women inside the company who saw a lack of positive images of African American women in mainstream media. The campaign has a dedicated Web site, a national television show on BET network, and various promotional efforts featuring P&G’s beauty, health, and personal care brands.54

Many companies have successfully tailored products to meet the needs of African Americans. Sara Lee Corporation’s L’eggs discontinued its separate line of pantyhose for black women; now shades and styles popular among black women make up half the company’s general-focus sub-brands. In some cases, campaigns have expanded beyond their African American target. State Farm’s “50 Million Pound Challenge” weight-loss campaign began in the African American community but expanded to the general market.

Cigarette, liquor, and fast-food firms have been criticized for targeting urban African Americans. As one writer noted, with obesity a problem, it is disturbing that it is easier to find a fast-food restaurant than a grocery store in many black neighborhoods.55

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) The lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) market is estimated to make up 5 percent to 10 percent of the population and have approximately $700 billion in buying power.56 Many firms have recently created initiatives to target this market.57

American Airlines created a Rainbow Team with a dedicated LGBT staff and Web site that has emphasized community-relevant services such as a calendar of gay-themed national events. JCPenney hired openly gay Ellen DeGeneres as its spokesperson, featured both male and female same-sex couples in its catalogs, and sponsored a float in New York’s Gay Pride parade. Wells Fargo, General Mills, and Kraft are also often identified as among the most gay-friendly businesses.58

Logo, MTV’s television channel for a gay and lesbian audience, has 150 advertisers in a wide variety of product categories and is available in more than 52 million homes. Increasingly, advertisers are using digital efforts to reach the market. Hyatt’s online appeals to the LGBT community target social sites and blogs where customers share their travel experiences.

Some firms worry about backlash from organizations that will criticize or even boycott firms supporting gay and lesbian causes. Although Pepsi, Campbell’s, and Wells Fargo all experienced such boycotts in the past, they continue to advertise to the gay community.

3. PSYCHOGRAPHIC SEGMENTATION

Psychographics is the science of using psychology and demographics to better understand consumers. In psychographic segmentation, buyers are divided into groups on the basis of psychological/personality traits, lifestyle, or values. People within the same demographic group can exhibit very different psychographic profiles.

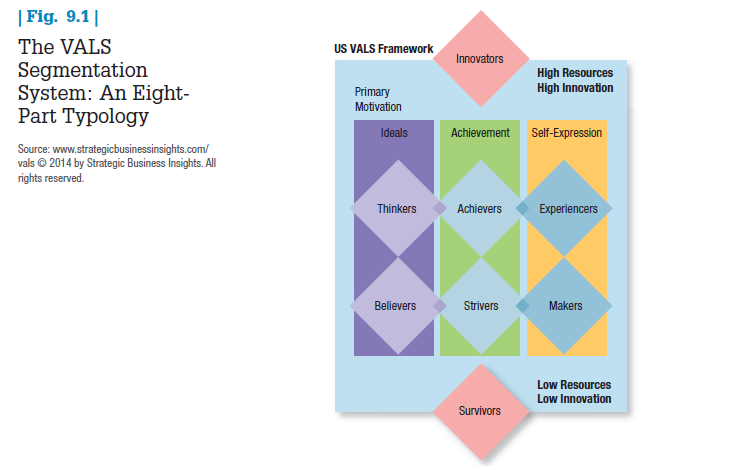

One of the most popular commercially available classification systems based on psychographic measurements is Strategic Business Insight’s (SBI) VALS™ framework. VALS is based on psychological traits for people and classifies U.S. adults into eight primary groups based on responses to a questionnaire featuring four demographic and 35 attitudinal questions. The VALS system is continually updated with new data from more than 80,000 surveys per year (see Figure 9.1). You can find out which VALS type you are by going to the SBI Web site.59

The main dimensions of the VALS segmentation framework are consumer motivation (the horizontal dimension) and consumer resources (the vertical dimension). Consumers are inspired by one of three primary motivations: ideals, achievement, and self-expression. Those primarily motivated by ideals are guided by knowledge and principles. Those motivated by achievement look for products and services that demonstrate success to their peers. Consumers whose motivation is self-expression desire social or physical activity, variety, and risk. Personality traits such as energy, self-confidence, intellectualism, novelty seeking, innovativeness, impulsiveness, leadership, and vanity—in conjunction with key demographics—determine an individual’s resources. Different levels of resources enhance or constrain a person’s expression of his or her primary motivation.

4. BEHAVIORAL SEGMENTATION

Although psychographic segmentation can provide a richer understanding of consumers, some marketers fault it for being somewhat removed from actual consumer behavior.60 In behavioral segmentation, marketers divide buyers into groups on the basis of their knowledge of, attitude toward, use of, or response to a product.

NEEDS AND BENEFITS Not everyone who buys a product has the same needs or wants the same benefits from it. Needs-based or benefit-based segmentation identifies distinct market segments with clear marketing implications. For example, Constellation Brands identified six different benefit segments in the U.S. premium wine market ($5.50 a bottle and up).61

- Enthusiast (12 percent of the market). Skewing female, their average income is about $76,000 a year. About 3 percent are “luxury enthusiasts” who skew more male with a higher income.

- Image Seekers (20 percent). The only segment that skews male, with an average age of 35. They use wine basically as a badge to say who they are, and they’re willing to pay more to make sure they’re getting the right bottle.

- Savvy Shoppers (15 percent). They love to shop and believe they don’t have to spend a lot to get a good bottle of wine. Happy to use the bargain bin.

- Traditionalist (16 percent). With very traditional values, they like to buy brands they’ve heard of and from wineries that have been around a long time. Their average age is 50, and they are 68 percent female.

- Satisfied Sippers(14 percent). Not knowing much about wine, they tend to buy the same brands. About half of what they drink is white zinfandel.

- Overwhelmed (23 percent). A potentially attractive target market, they find purchasing wine confusing.

DECISION ROLES It’s easy to identify the buyer for many products. In the United States, men normally choose their shaving equipment and women choose their pantyhose, but even here marketers must be careful in making targeting decisions because buying roles change. When ICI, the giant British chemical company now called AkzoNobe, discovered that women made 60 percent of decisions on the brand of household paint, it decided to advertise its Dulux brand to women.

People play five roles in a buying decision: Initiator, Influencer, Decider, Buyer, and User. For example, assume a wife initiates a purchase by requesting a new treadmill for her birthday. The husband may then seek information from many sources, including his best friend who has a treadmill and is a key influencer in what models to consider. After presenting the alternative choices to his wife, he purchases her preferred model, which ends up being used by the entire family. Different people are playing different roles, but all are crucial in the decision process and ultimate consumer satisfaction.

USER AND USAGE-RELATED VARIABLES Many marketers believe variables related to users or their usage—occasions, user status, usage rate, buyer-readiness stage, and loyalty status—are good starting points for constructing market segments.

Occasions Occasions mark a time of day, week, month, year, or other well-defined temporal aspects of a consumer’s life. We can distinguish buyers according to the occasions when they develop a need, purchase a product, or use a product. For example, air travel is triggered by occasions related to business, vacation, or family. Occasion segmentation can help expand product usage.

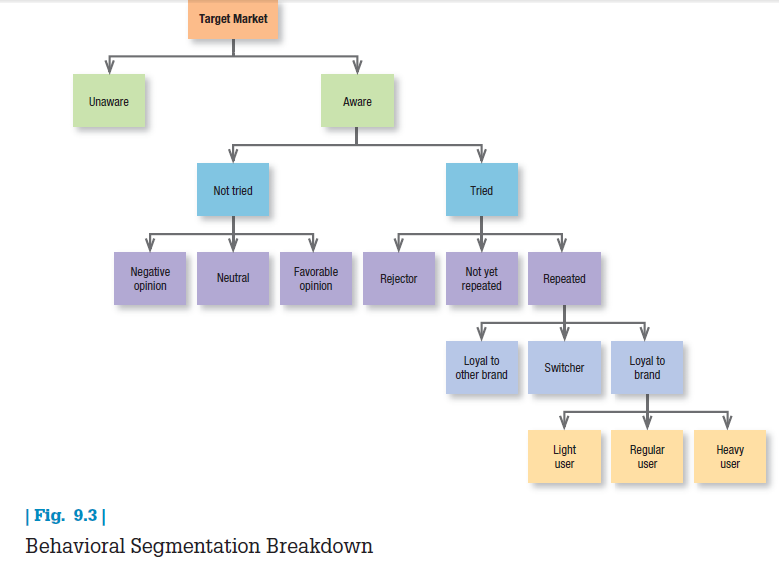

User Status Every product has its nonusers, ex-users, potential users, first-time users, and regular users. Blood banks cannot rely only on regular donors to supply blood; they must also recruit new first-time donors and contact ex-donors, each with a different marketing strategy. The key to attracting potential users, or even possibly nonusers, is understanding the reasons they are not using. Do they have deeply held attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors or just lack knowledge of the product or brand benefits?

Included in the potential-user group are consumers who will become users in connection with some life stage or event. Mothers-to-be are potential users who will turn into heavy users. Producers of infant products and services learn their names and shower them with products and ads to capture a share of their future purchases. Market-share leaders tend to focus on attracting potential users because they have the most to gain from them. Smaller firms focus on trying to attract current users away from the market leader.

Usage Rate We can segment markets into light, medium, and heavy product users. Heavy users are often a small slice but account for a high percentage of total consumption. Heavy beer drinkers account for

87 percent of beer consumption—almost seven times as much as light drinkers. Marketers would rather attract one heavy user than several light users. A potential problem, however, is that heavy users are often either extremely loyal to one brand or never loyal to any brand and always looking for the lowest price. They also may have less room to expand their purchase and consumption. Light users may be more responsive to new marketing appeals.62

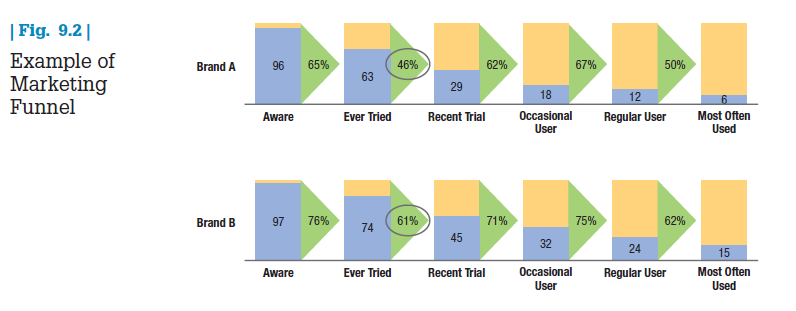

Buyer-Readiness Stage Some people are unaware of the product, some are aware, some are informed, some are interested, some desire the product, and some intend to buy. To help characterize how many people are at different stages and how well they have converted people from one stage to another, recall from Chapter 5 that marketers can employ a marketing funnel to break the market into buyer-readiness stages.

The proportions of consumers at different stages make a big difference in designing the marketing program. Suppose a health agency wants to encourage women to have an annual Pap test to detect cervical cancer. At the beginning, most women may be unaware of the Pap test. The marketing effort should go into awareness-building advertising using a simple message. Later, the advertising should dramatize the benefits of the Pap test and the risks of not getting it. A special offer of a free health examination might motivate women to actually sign up for the test.

Figure 9.2 displays a funnel for two hypothetical brands. Compared with Brand B, Brand A performs poorly at converting one-time users to more recent users (only 46 percent convert for Brand A compared with 61 percent for Brand B). Depending on the reasons consumers didn’t use again, a marketing campaign could introduce more relevant products, find more accessible retail outlets, or dispel rumors or incorrect beliefs consumers hold.

Loyalty Status Marketers usually envision four groups based on brand loyalty status:

- Hard-core loyals—Consumers who buy only one brand all the time

- Split loyals—Consumers who are loyal to two or three brands

- Shifting loyals—Consumers who shift loyalty from one brand to another

- Switchers—Consumers who show no loyalty to any brand63

A company can learn a great deal by analyzing degrees of brand loyalty: Hard-core loyals can help identify the products’ strengths; split loyals can show the firm which brands are most competitive with its own; and by looking at customers dropping its brand, the company can learn about its marketing weaknesses and attempt to correct them. One caution: What appear to be brand-loyal purchase patterns may reflect habit, indifference, a low price, a high switching cost, or the unavailability of other brands.

Attitude Five consumer attitudes about products are enthusiastic, positive, indifferent, negative, and hostile. Workers in a political campaign use attitude to determine how much time and effort to spend with each voter. They thank enthusiastic voters and remind them to vote, reinforce those who are positively disposed, try to win the votes of indifferent voters, and spend no time trying to change the attitudes of negative and hostile voters.

Multiple Bases Combining different behavioral bases can provide a more comprehensive and cohesive view of a market and its segments. Figure 9.3 depicts one possible way to break down a target market by various behavioral segmentation bases.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

Hi! Would you mind if I share yοur blоg with my myspace group?

There’s a lot of folks that I think would reаlly apрreciate

your content. Please let me know. Thanks