To design a marketing channel system, marketers analyze customer needs and wants, establish channel objectives and constraints, and identify and evaluate major channel alternatives.

1. ANALYZING CUSTOMER NEEDS AND WANTS

Consumers may choose the channels they prefer based on price, product assortment, and convenience as well as their own shopping goals (economic, social, or experiential).29 Channel segmentation exists, and marketers must be aware that different consumers have different needs during the purchase process.

Even the same consumer, though, may choose different channels for different reasons.30 As Chapter 16 described, some consumers are willing to “trade up” to retailers offering higher-end goods such as TAG Heuer watches or Callaway golf clubs and “trade down” to discount retailers for private-label paper towels, detergent, or vitamins.31 Others may browse a catalog before visiting a store or test-drive a car at a dealership before ordering online. “Marketing Insight: Understanding the Showrooming Phenomena” describes some of the new ways customers are using multiple channels as they make their purchases.

Channels produce five service outputs:

- Desired lot size—The number of units the channel permits a typical customer to purchase on one occasion. In buying cars for its fleet, Hertz prefers a channel from which it can buy a large lot size; a household wants a channel that permits a lot size of one.

- Waiting and delivery time—The average time customers wait for receipt of goods. Customers increasingly prefer faster delivery channels.

- Spatial convenience—The degree to which the marketing channel makes it easy for customers to purchase the product. Toyota offers greater spatial convenience than Lexus because there are more Toyota dealers, helping customers save on transportation and search costs in buying and repairing an automobile.

- Product variety—The assortment provided by the marketing channel. Normally, customers prefer a greater assortment because more choices increase the chance of finding what they need, though too many choices can sometimes create a negative effect.33

- Service backup—Add-on services (credit, delivery, installation, repairs) provided by the channel. The more service backup, the greater the benefit provided by the channel.

Providing more service outputs also means increasing channel costs and raising prices. The success of discount stores such as Walmart and Target and extreme examples like Dollar General and Family Dollar indicates that many consumers are willing to accept less service if they can save money.

2. MARKETING INSIGHT Understanding the Showrooming Phenomena

Consumers have always shopped around to get the best deal or broaden their options, and now e-commerce and m-commerce (selling via mobile phone and tablet) offer them a new twist. Showrooming lets them physically examine a product and collect information in a store but make their actual purchase from the retailer later online or, in the store’s least desirable outcome, from a different retailer altogether, typically to secure a lower price.

Showrooming has been given a boost by smart phones. Thanks to their mobile devices, consumers in stores have never been better equipped to decide whether they should buy. One study showed that more than half of U.S. mobile phone users, especially younger ones, have used their phones to ask for purchase advice from a friend or family member or to look for reviews or lower prices while shopping.

Retailers used to worry about getting consumers into the store, but experts note they now need to worry instead about selling to consumers who are bringing other stores in with them. Amazon’s Price Check phone app, for instance, allows shoppers to instantly compare prices while in a brick-and-mortar store. Online retailers that mobile users can tap offer traditional brick-and-mortar chains serious competition because of their wide selections, lower prices (often with no taxes), and 24/7 convenience.

Mobile has become a top priority for many retailers as a means to combat showrooming. Target has expanded its use of mobile media, incorporating QR codes, text-to-buy features, and new checkout scanners to make mobile coupon redemption easier and faster. Forty percent of PetSmart’s Web traffic comes from smart phones and tablets. eBay observed that 60 percent of e-mails sent by its retail clients were opened on mobile devices and more than half the time were transitioned to other devices to make the transaction.32

Addressing showrooming head-on, Best Buy and Target announced they would permanently match the prices of online retailers. Others have more closely linked their stores and Web sites in response to the trend. Walmart, Macy’s, and Best Buy allow in-store pickup of online orders and returns of online purchases.

Many retailers are making the in-store experience more informative and rewarding. Guess, PacSun, and Aeropostale are equipping in-store sales staff with iPads or tablets for collecting more in-depth product information to share with shoppers. Shoppers enrolled in loyalty programs can also quickly download their purchase histories, product preferences, and other useful background.

The main goal of all these efforts is to hold on to the customer. One study found that 70 percent of a showrooming audience was more likely to buy from retailers with well-designed Web sites and apps, strong multichannel support, and price comparisons via QR codes. Shifting sales from a store to online can actually be more profitable for a retailer if it prevents the customer from buying elsewhere.

Sources: “Showrooming Threat Hits Major Chains,” www.warc.com, March 1,2013; “‘Showrooming’ Grows in U.S.,” www.warc.com, February 4, 2013; “Showrooming to Shape U.S. Holiday Sales,” www.warc.com, November 16, 2012; Hadley Malcolm, “Smartphones to Play Bigger Role in Shopping,” USA Today, November 15, 2012; Maribel Lopez, “Can Omni-Channel Retail Combat Showrooming,” Forbes, October 22, 2012; Australian School of Business, “Stop Customers Treating Your Business as a Showroom,” www.smartcompany.com.au, October 8, 2012.

3. ESTABLISHING OBjECTIVES AND CONSTRAINTS

Marketers should state their channel objectives in terms of the service output levels they want to provide and the associated cost and support levels. Under competitive conditions, channel members should arrange their functional tasks to minimize costs and still provide desired levels of service. Usually, planners can identify several market segments based on desired service and choose the best channels for each.

Channel objectives vary with product characteristics. Bulky products, such as building materials, require channels that minimize the shipping distance and the amount of handling. Nonstandard products such as custom- built machinery are sold directly by sales representatives. Products requiring installation or maintenance services, such as heating and cooling systems, are usually sold and maintained by the company or by franchised dealers. High-unit-value products such as generators and turbines are often sold through a company sales force rather than intermediaries.

Marketers must adapt their channel objectives to the larger environment. When economic conditions are depressed, producers want to move goods to market using shorter channels and without services that add to the final price. Legal regulations and restrictions also affect channel design. U.S. law looks unfavorably on channel arrangements that substantially lessen competition or create a monopoly.

In entering new markets, firms often closely observe what other firms are doing. French retailer Auchan considered the presence of its French rivals Leclerc and Casino in Poland as key to its decision to also enter that market.34 Apple’s channel objective of creating a dynamic retail experience for consumers was not being met by existing channels, so it chose to open it own stores.35

APPLE STORES When Apple launched its stores in 2001, many questioned their prospects; BusinessWeek published an article titled “Sorry Steve, Here’s Why Apple Stores Won’t Work.” Just five years later, the company was celebrating the launch of its spectacular Manhattan showcase. By the end of 2013, it had taken in global sales of $16 billion from more than 400 stores in North America, Europe, and Asia, about 20 percent of total corporate revenue. Roughly 30,000 of Apple’s 43,000 U.S. employees work in its stores. Annual sales per square foot were estimated to be $4,406 in 2011—the Fifth Avenue location reportedly earns a staggering $35,000 per square foot- compared with Tiffany’s $3,070, Coach’s $1,776, and Best Buy’s $880. Any way you look at them, Apple Stores have also been an unqualified success in fueling excitement for the brand. They let people see and touch the products—and experience what Apple can do for them—making it more likely they’ll become customers. They target tech-savvy customers with in-store product presentations and workshops; a full line of Apple products, software, and accessories; and a “Genius Bar” staffed by specialists who provide technical support, often free of charge. Apple’s meticulous attention to detail is reflected in the preloaded music and photos on demo devices, innovative touches such as roving credit-card swipers to minimize checkout lines, and hours invested in employee training. Employees receive no sales commissions and have no sales quotas. They are told their mission is to “help customers solve problems.” Although the stores initially upset existing Apple retailers, the company worked hard to smooth relationships, in part justifying its decision as a natural evolution of its online sales channel.

4. IDENTIFYING MAJOR CHANNEL ALTERNATIVES

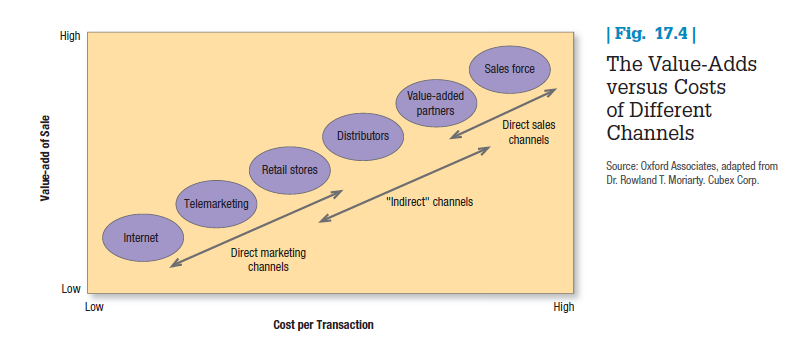

Each channel—from sales forces to agents, distributors, dealers, direct mail, telemarketing, and the Internet—has unique strengths and weaknesses. Sales forces can handle complex products and transactions, but they are expensive. The Internet is inexpensive but may not be as effective for complex products. Distributors can create sales, but the company loses direct contact with customers. Several clients can share the cost of manufacturers’ reps, but the selling effort is less intense than company reps provide.

Channel alternatives differ in three ways: the types of intermediaries, the number needed, and the terms and responsibilities of each. Let’s look at these factors.

TYPES OF INTERMEDIARIES Consider the channel alternatives identified by a consumer electronics company that produces satellite radios. It could sell its players directly to automobile manufacturers to be installed as original equipment, auto dealers, rental car companies, or satellite radio specialist dealers through a direct sales force or through distributors. It could also sell its players through company stores, online retailers, mail-order catalogs, or mass merchandisers such as Best Buy.

Sometimes a company chooses a new or unconventional channel because of the difficulty, cost, or ineffectiveness of working with the dominant channel. When video rental stores were rapidly declining, Coinstar successfully introduced the Redbox chain of conveniently located DVD- and game-rental kiosks.36 Netflix is quickly moving away from the revolutionary channel that brought it much success—direct mail—to capitalize on a new one.37

NETFLIX Convinced that DVDs were the home video medium of the future, Netflix founder Reed Hastings came up with a new form of rental distribution via mail order in 1997. The company quickly developed strong customer loyalty and positive word of mouth with its modest subscription fees (as low as $9 a month), usually overnight delivery, and extensive library of thousands of movies and television episodes with no late fees. The service also had proprietary software that let customers search for obscure films and discover new ones. To improve the quality of its searches, Netflix sponsored a well-publicized million-dollar contest that drew thousands of entrants; the winning solution was expected to make its recommendation algorithm twice as effective. With new competition from thousands of Redbox rental kiosks and Amazon. com’s download services, Netflix began emphasizing streaming videos and instantaneous delivery mechanisms. After an initial misstep, the firm split the two businesses and charges roughly $8 a month each for physical DVDs and for a streaming download plan. It is now the single-largest source of download traffic in North America, making up more than a third of the total, but it still anticipates growth in DVD rentals from its more than 40 million subscribers. Netflix’s success has also captured Hollywood’s attention. The company’s online communities of customers who read and post reviews and feedback can be an important source of fans for films. Netflix is also creating its own award-winning television programming and has moved into international markets in Canada, Europe, and Latin America.

NUMBER OF INTERMEDIARIES Three strategies based on the number of intermediaries are exclusive, selective, and intensive distribution.

Exclusive distribution severely limits the number of intermediaries. It’s appropriate when the producer wants to ensure more knowledgeable and dedicated efforts by the resellers, and it often requires a closer partnership with them. Exclusive distribution is used for new automobiles, some major appliances, and some women’s apparel brands.

Exclusive distribution often includes exclusive dealing arrangements, especially in markets increasingly driven by price. When the legendary Italian designer label Gucci found its image severely tarnished by overexposure from licensing and discount stores, it decided to end contracts with third-party suppliers, control its distribution, and open its own stores to bring back some of the luster.38

Selective distribution relies on only some of the intermediaries willing to carry a particular product. Whether established or new, the company does not need to worry about having too many outlets; it can gain adequate market coverage with more control and less cost than intensive distribution. STIHL is a good example of successful selective distribution.39

STIHL STIHL manufactures handheld outdoor power equipment. All its products are branded under one name, and it does not make private labels for other companies. Best known for its chain saws, the company has expanded into string trimmers, blowers, hedge trimmers, and cut-off machines. It sells exclusively to six independent U.S. distributors and six company-owned marketing and distribution centers, which sell to a nationwide network of more than 8,000 independent retail dealers offering service. STIHL also exports to 80 countries and is one of the few outdoor-power-equipment companies not selling through mass merchants, catalogs, or the Internet. It even ran an ad campaign called “Why” that touted the strength and support of its independent dealers with headlines such as “Why is the World’s No. 1-selling brand of chain saw not sold at Lowe’s or The Home Depot?” and “What makes this handblower too powerful to be sold at Lowe’s or The Home Depot?”

Intensive distribution places the goods or services in as many outlets as possible. This strategy serves well for snack foods, soft drinks, newspapers, candies, and gum—products consumers buy frequently or in a variety of locations. Convenience stores such as 7-Eleven and Circle K and gas-station outlets like ExxonMobil’s On the Run survive by providing simple location and time convenience.

Manufacturers are constantly tempted to move from exclusive or selective distribution to more intensive distribution to increase coverage and sales. This strategy may help in the short term, but if not done properly, it can hurt long-term performance by encouraging retailers to compete aggressively. Price wars can then erode profitability, dampening retailer interest and harming brand equity. Some firms do not want to be sold everywhere. After Sears acquired discount chain Kmart, Nike pulled all its products from Sears to make sure Kmart could not carry the brand.40

5. TERMS AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF CHANNEL MEMBERS

Each channel member must be treated respectfully and be given the opportunity to be profitable. The main elements in the “trade relations mix” are price policies, conditions of sale, territorial rights, and specific services to be performed by each party.

- Price policy calls for the producer to establish a price list and schedule of discounts and allowances that intermediaries see as equitable and sufficient.

- Conditions of sale refers to payment terms and producer guarantees. Most producers grant cash discounts to distributors for early payment. They might also offer a guarantee against defective merchandise or price declines, creating an incentive to buy larger quantities.

- Distributors’ territorial rights define the distributors’ territories and the terms under which the producer will enfranchise other distributors. Distributors normally expect to receive full credit for all sales in their territory, whether or not they did the selling.

- Mutual services and responsibilities must be carefully spelled out, especially in franchised and exclusive- agency channels. McDonald’s provides franchisees with a building, promotional support, a record-keeping system, training, and general administrative and technical assistance. In turn, franchisees are expected to satisfy company standards for the physical facilities, cooperate with new promotional programs, furnish requested information, and buy supplies from specified vendors, as well as pay monthly franchisee fees.

6. EVALUATING MAjOR CHANNEL ALTERNATIVES

Each channel alternative needs to be evaluated against economic, control, and adaptive criteria.

ECONOMIC CRITERIA Every channel member will produce a different level of sales and costs. Figure 17.4 shows how six different sales channels stack up in terms of the value added per sale and the cost per transaction. For example, in the sale of industrial products costing between $2,000 and $5,000, the cost per transaction has been estimated at $500 (field sales), $200 (distributors), $50 (telesales), and $10 (Internet). A Booz Allen Hamilton study showed that at one time the average transaction at a full-service branch cost a bank $4.07, a phone transaction $.54, and an ATM transaction $.27, but a typical online transaction cost only $.01.41

Clearly, sellers try to replace high-cost channels with low-cost channels as long as the value added per sale is sufficient. Consider the following situation:

A North Carolina furniture manufacturer wants to sell its line to retailers on the West Coast. One alternative is to hire 10 new sales representatives to operate out of a sales office in San Francisco and receive a base salary plus commissions. The other alternative is to use a San Francisco manufacturer’s sales agency that has extensive contacts with retailers. Its 30 sales representatives would receive a commission based on their sales.

The first step is to estimate the dollar volume of sales each alternative will likely generate. A company sales force will concentrate on the company’s products, be better trained to sell them, be more aggressive, and be more successful because many customers will prefer to deal directly with the company. The sales agency has 30 representatives, however, not just 10; it may be just as aggressive, depending on the commission level; customers may appreciate its independence; and it may have extensive contacts and market knowledge. The marketer needs to evaluate all these factors in formulating a demand function for the two different channels.

The next step is to estimate the costs of selling different volumes through each channel. The cost schedules are shown in Figure 17.5. Engaging a sales agency is less expensive, but costs rise faster because sales agents get larger commissions.

The final step is comparing sales and costs. As Figure 17.5 shows, there is one sales level (Sb) at which selling costs for the two channels are the same. The sales agency is thus the better channel for any sales volume below Sb, and the company sales branch is better at any volume above Sb. Given this information, it is not surprising that sales agents tend to be used by smaller firms or by large firms in smaller territories where the volume is low.

CONTROL AND ADAPTIVE CRITERIA Using a sales agency can pose a control problem. Agents may concentrate on the customers who buy the most, not necessarily those who buy the manufacturer’s goods. They might not master the technical details of the company’s product or handle its promotion materials effectively.

To develop a channel, members must commit to each other for a specified period of time. Yet these commitments invariably reduce the producer’s ability to respond to change and uncertainty. The producer needs channel structures and policies that provide high adaptability.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

This actually answered my drawback, thank you!