Researchers have to decide what type of approach they want to use to collect and to analyze their data. In other words, how they are going to tackle the empirical side of their research. We begin this section by examining what distinguishes a qualitative from a quantitative approach. We then show how these two approaches can be complementary.

1. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches

It is conventional in research to make a distinction between the qualitative and the quantitative. However this distinction is both equivocal and ambiguous.1 The distinction is equivocal as it is based on a multiplicity of criteria. In consulting works on research methodology we find, in sections discussing the distinction between qualitative and quantitative, references to ‘qualitative or quantitative data’ (Downey and Ireland, 1979; Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Miles, 1979; Miles and Huberman, 1984b; Silverman, 1993); to quantitative and qualitative variables (Evrard et al., 1993; Lambin, 1990), and to ‘qualitative methods’ (Jick, 1979; Silverman, 1993; Van Maanen, 1979). The distinction between qualitative and quantitative is, moreover, ambiguous because none of these criteria allow for an absolute distinction between the qualitative and the quantitative approach. We will turn now to a critical examination of the various criteria involved: the nature of the data, the orientation of the research, the objective or subjective character of the results obtained and the flexibility of the research.

As data collection methods, which are among the distinguishing characteristics of both qualitative and quantitative approaches, are discussed at length in another chapter in this book (Chapter 9), we will restrict our discussion here to other distinguishing characteristics.

1.1. The qualitative/quantitative distinction and the nature of our data

Does the distinction between qualitative and quantitative go back to the very nature of a researcher’s data?

Many authors distinguish between qualitative and quantitative data. For Miles and Huberman (1984b), qualitative data corresponds to words rather than figures. Similarly, Yin (1989: 88) explains that ‘numerical data’ provides quantitative information, while ‘non-numerical data’ furnishes information that is clearly of a qualitative nature. All the same, the nature of the data does not necessarily impose an identical method of processing it. The researcher can very well carry out, for example, a statistical and consequently quantitative analysis of nominal variables.

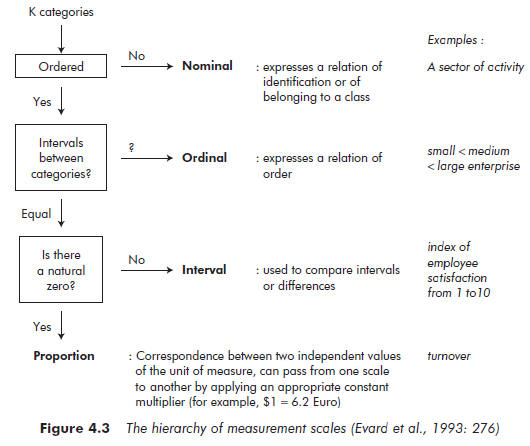

According to Evrard et al. (1993: 35), qualitative data corresponds to variables measured on nominal and ordinal (non-metric) scales, while quantitative data is collected using interval scales and proportion scales. These scales can be arranged hierarchically according to the quality of their mathematical properties. As shown in Figure 4.3, this hierarchy goes from a nominal scale, the weakest one from a mathematical point of view, to the proportional scale, the best of the measurement scales.

As Figure 4.3 shows, measuring variables on nominal scales allows us to establish relationships of identification or of belonging of a class. The fact that these classes may be identified by numbers (a department number, for example, or an arbitrarily chosen number) does not in any way change their properties. The one statistical calculation permitted is that of frequency.

Often a classification can be obtained using variables measured on ordinal scales, but the origin of the scale remains arbitrary. If the intervals between categories are unequal, statistical calculations are limited to measures of position (median, quartiles, deciles …). Arithmetical calculations cannot be performed with this data. Once the intervals between categories become equal, however, we can speak of interval scales. More statistical calculations can be carried out on variables measured on this type of scale, as here we move into data said to be ‘quantitative’, or to ‘metric’ scales, for which we can compare intervals and determine ratios of differences or distances. Means and standard deviations can be calculated, however, zero is defined arbitrarily.

The best-known example of an interval scale is that used to measure temperature. We know that 0 degrees on the Celsius scale, the freezing point of water, corresponds to 32 degrees on the Fahrenheit scale. We can convert a data item from one scale to another by a positive linear transformation (y = ax + b, where a > 0). However, if there is no natural zero, relationships cannot be established between absolute quantities. For example, it is misleading to say that ‘yesterday was half as hot as today’, when we mean that ‘the temperature was 50 per cent less in degrees Fahrenheit than today’. If the two temperatures are converted into Celsius, it will be seen that ‘half as hot’ is not correct. The arbitrary choice of zero on the measuring scale has an effect on the relationship between the two measurements.

Where a natural zero exists, we come to proportional scales. Common examples include measurements of money, length or weight. This kind of data is therefore the richest in terms of the possible statistical calculations that can be operated on it, since the researcher will be able to analyze relationships in terms of absolute values of variables such as wage levels or company seniority.

The different aspects of qualitative and quantitative data that we have considered in this chapter clearly show that the nature of the collected data does not dictate the employment of a qualitative or a quantitative research approach. To choose between a qualitative or a quantitative approach we have to evaluate other criteria.

1.2. The qualitative/quantitative distinction in relation to the orientation of the research: to construct or to test

Research in management is characterized by two main preoccupations: constructing and testing theoretical objects. When researchers direct their work towards verification, they have a clear and definite idea of what they are looking for. On the other hand, if they are carrying out explorative research, typified by theoretical construction, researchers are often far less sure of what they may find (see Chapter 3).

It is conventional to correlate investigation with a qualitative approach and verification with a quantitative. Silverman, for example, distinguishes between two ‘schools’ in the social sciences, one oriented towards the quantitative testing of theories, and the other directed at qualitatively developing theories (1993: 21). Once again, however, we find that this association is a received idea – researchers can equally well adopt a quantitative or a qualitative approach whether they are constructing or testing (see Chapter 3). ‘There is no fundamental clash between the purposes and capacities of qualitative and quantitative methods or data … Each form of data is useful for both verification and generation of theory’ (Glaser and Strauss, 1967: 17-18).

We should point out here, though, that researchers rarely choose a qualitative approach with the sole intention of testing a theory. This choice is generally accompanied by a fairly definite orientation towards construction. This tendency can be explained by the cost, particularly in time, of using a qualitative approach just to test a theory. If the test turns out to be positive, the researcher will have no choice but to test it again – by conducting another data collection and analysis process. The qualitative approach in effect locks the researcher into a process of falsification, as the only aim can be to refute the theory and not to validate it in any way.

The qualitative approach is not designed to evaluate to what extent one can generalize from an existing theory. In his discussion of the case study, which he positions within the qualitative method, Stake argues that ‘by counter-example, the case study invites a modification of the generalization’ (1995: 8). This modification involves a construction. The limitation of qualitative approaches lies in the fact that such studies are necessarily carried out within a fairly delimited context. Although a researcher can increase the external validity of a qualitative study by including several contexts in the analysis, in accordance with a replication logic (see Chapter 10), the limitations of the qualitative approach in terms of generalization lead us to attribute more external validity to quantitative approaches. Conversely, the qualitative approach gives a greater guarantee of the internal validity of results. Rival explanations of the phenomenon being studied are often far easier to evaluate than they are when a quantitative approach is taken, as researchers are in a better position to cross-check their data. The qualitative approach also increases the researcher’s ability to describe a complex social system (Marshall and Rossman, 1989).

The choice between a qualitative and a quantitative approach therefore seems to be dictated primarily in terms of each approach’s effectiveness in relation to the orientation of the research; that is, whether one is constructing or testing.

Guarantees of internal and external validity should be considered in parallel, whatever type of research is being carried out. But in order to choose between a qualitative and a quantitative approach, researchers have to decide on the priority they will give to the quality of causal links between variables, or to the generalization of their results. Of course, it would be ideal to assure the greatest validity in results by employing both of these approaches together.

1.3. Qualitative/quantitative research for objective/ subjective results

It is generally acknowledged that quantitative approaches offer a greater assurance of objectivity than do qualitative approaches. The necessary strictness and precision of statistical techniques argue for this view. It is, then, not surprising that the quantitative approach is grounded in the positivist paradigm (Silverman, 1993).

While the objective or subjective nature of research results is often seen as forming a divisive line between qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are in fact several areas of possible subjectivity in management research, depending on the particular type of qualitative approach taken. A number of proponents of the qualitative approach have also discussed ways of reducing the subjectivity historically attributed to this research tradition.

According to Erickson (1986), the most distinctive feature of qualitative investigation is its emphasis on interpretation – not simply that of the researcher but, more importantly, that of the individuals who are studied. This emphasis is comparable to that of ethnographic research, which seeks ‘to reconstruct the categories used by subjects to conceptualize their own experience and world view’ (Goetz and LeCompte, 1981: 54). Other writers, however, emphasize the subjectivity of the researcher more than that of the subjects. According to Stake (1995), researchers must position themselves as interpreters of the field they are studying, even if their own interpretation may be more labored than that of the research subjects. In fact, the qualitative approach allows for both the subjectivity of the researcher and that of the subjects at the same time. It offers an opportunity to confront multiple realities, for it ‘exposes more directly the nature of the transaction between investigator and respondent (or object) and hence makes easier an assessment of the extent to which the phenomenon is described in terms of (is biased by) the investigator’s own posture’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985: 40).

However, the qualitative approach does not rule out an epistemological posture of objectivity of the research with regard to the world that it is studying. This criterion of objectivity can be seen as an ‘intersubjective agreement’. ‘If multiple observers can agree on a phenomenon, their collective judgment can be said to be objective’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985: 292). Some proponents of the qualitative approach, notably Glaser and Strauss (1967), have developed a positivist conception of it. For Miles and Huberman (1984b) while the source of social phenomena may be in the minds of the subjects, these phenomena also exist in the real world. These authors argue for an amended positivism, advocating the construction of a logical chain of evidence and proof to increase the objectivity of results.

To sum up, data collection and analysis must remain consistent with an explicit epistemological position on the part of the researcher. Although the qualitative approach allows the researcher to introduce a subjectivity that is incompatible with the quantitative approach, it should not, however, be limited to a constructivist epistemology.

1.4. The qualitative/quantitative distinction in relation to the flexibility of the study

The question of the flexibility available to the researcher in conducting his or her research project is another crucial factor to consider in choosing whether to use a qualitative or a quantitative approach.

When a qualitative approach is used, the research question can be changed midway, so that the results are truly drawn from the field (Stake, 1995). It is obviously difficult to modify the research question during the more rigid process that is required by the quantitative approach, taking into account the cost that such a modification would entail. With the qualitative approach, too, the researcher usually has the advantage of greater flexibility in collecting data, whereas the quantitative approach usually involves a stricter schedule. Another problem is that once a questionnaire has been administered to a large sample of a population, it can be difficult to assess new rival explanations without taking the research program back to the draft stage.

2. Combined Approaches: Using Sequential Processes and Triangulation Strategies

One way researchers can exploit the complementary nature of qualitative and quantitative approaches is by using a sequential process:

Findings from exploratory qualitative studies may … provide a starting point for further quantitative or qualitative work. In multi-method projects, group discussions and in-depth interviews are frequently used in piloting to clarify concepts and to devise and calibrate instrumentation for inclusion in structured questionnaires.

(Walker, 1985: 20)

The qualitative approach can in this way constitute a necessary and remunerative stage in an essentially quantitative study. Given the considerable degree of irreversibility inherent to the quantitative approach, the success of such a research project very much depends on the researcher taking necessary precautions along the way.

Another practical way researchers can combine qualitative and quantitative approaches is by means of a triangulation. This involves using the two approaches simultaneously to take advantage of their respective qualities. ‘The achievements of useful hypothetically realistic constructs in a science requires multiple methods focused on the diagnosis of the same construct from independent points of observation through a kind of triangulation’ (Campbell and Fiske, 1959: 81). The idea is to consider a formalized problem by formalizing along two complementary axes. The differential effect can then provide invaluable information for the researcher. Triangulation strategies aim to improve the precision of both measurement and description.

Triangulation allows the research design to be put to the test, by ensuring that findings are not just a reflection of the methodology used (Bouchard, 1976). This does not simply mean commingling the two types of data and methods. Using complementary data does not of itself constitute a triangulation, but a natural action used in the majority of research projects (Downey and Ireland, 1979). It is a mistake to think that the ‘qualitative’ researcher does not make use of quantitative data, or that he or she is somehow opposed to measurement (Miles, 1979). The fact that a researcher uses a symbolic numerical system or a symbolic verbal system to translate an observed reality does not necessarily define the type of approach they are using. In their manual on qualitative analysis, for example, Miles and Huberman (1984b) suggest counting data items to highlight recurrence, for the reason that figures are more economical and easier to manipulate than are words, as well as having greater visibility in terms of trends.

The combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches, that is, their complementary and dialectical use, enables researchers to institute a dialogue distinguishing between what is observed (the subject of the research) and the two ways of symbolizing it:

Qualitative methods represent a mixture of the rational, serendipitous, and intuitive in which the personal experiences of the organizational researcher are often key events to be understood and analyzed as data. Qualitative investigators tend also to describe the unfolding of social processes rather than the social structures that are often the focus of quantitative researchers.

(Van Maanen, 1979: 520)

Triangulation allows the researcher to benefit from the advantages of the two approaches, counterbalancing the defects of one approach with the qualities of the other (Jick, 1979).

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021