Before we can give due thought to the question of what knowledge is, we must first consider the related question of the nature of reality. Does reality exist independently of the observer, or is our perception of reality subjective. What part of ‘reality’ can we know?

1. A Positivist Understanding of Reality

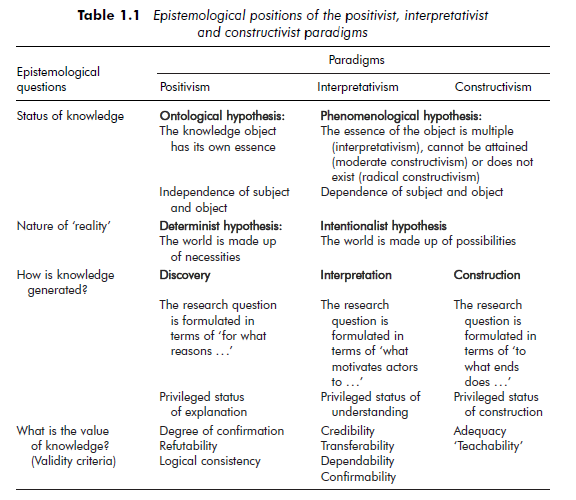

For positivists, reality exists in itself. It has an objective essence, which researchers must seek to discover. The object (reality) and the subject that is observing or testing it are independent of each other. The social or material world is thus external to individual cognition – as Burrell and Morgan put it (1979: 4): ‘Whether or not we label and perceive these structures, the realists maintain, they still exist as empirical entities.’ This independence between object and subject has allowed positivists to propound the principle of objectivity, according to which a subject’s observation of an external object does not alter the nature of that object. This principle is defined by Popper (1972: 109): ‘Knowledge in this objective sense is totally independent of anybody’s claim to know; it is also independent of anybody’s belief, or disposition to assent; or to assert, or to act. Knowledge in the objective sense is knowledge without a knowing subject.’ The principle of the objectivity of knowledge raises various problems when it is applied in the social sciences. Can a person be his or her own object? Can a subject really observe its object without altering the nature of that object? Faced with these different questions, positivist researchers will exteriorize the object they are observing. Durkheim (1982) thus exteriorizes social events, which he considers as ‘things’. He maintains that ‘things’ contrast with ideas in the same way as our knowledge of what is exterior to us contrasts with our knowledge of what is interior. For Durkheim, ‘things’ encompasses all that which the mind can only understand if we move outside our own subjectivity by means of observation and testing.

In organizational science, this principle can be interpreted as follows. Positivist researchers examining the development of organizational structures will take the view that structure depends on a technical and organizational reality that is independent of themselves or those overseeing it. The knowledge produced by the researcher observing this reality (or reconstructing the cause- and-effect chain of structural events) can lead to the development of an objective knowledge of organizational structure.

In postulating the essence of reality and, as a consequence, subject-object independence, positivists accept that reality has its own immutable and quasiinvariable laws. A universal order exists, which imposes itself on everything: individual order is subordinate to social order, social order is subordinate to ‘vital’ order and ‘vital’ order is subordinate to material order. Human beings are subject to this order. They are products of an environment that conditions them, and their world is made up of necessities. Freedom is restricted by invariable laws, as in a determinist vision of the social world. The Durkheimian notion of social constraint is a good illustration of the link between the principle of external reality and that of determinism. For Durkheim (1982), the notion of social constraint implies that collective ways of acting or thinking have a reality apart from the individuals who constantly comply with them. The individual finds them already shaped and, in Durkheim’s (1982) view, he or she cannot then act as if they do not exist, or as if they are other than what they are.

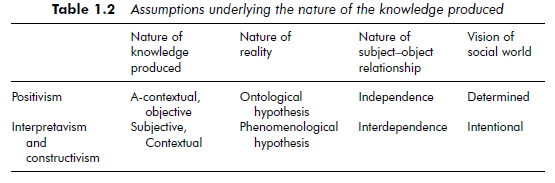

Consequently, the knowledge produced by positivists is objective and a-contextual – in that it relates to revising existing laws and to an immutable reality that is external to the individual and independent of the context of interactions between actors.

2. A Subjective Reality?

In the rival interpretativist and constructivist paradigms, reality has a more precarious status. According to these paradigms, reality remains unknowable because it is impossible to reach it directly. Radical constructivism declares that ‘reality’ does not exist, but is invented, and great caution must be used when using the term (Glasersfeld, 1984). Moderate constructivists do not attempt to answer this question. They neither reject nor accept the hypothesis that reality exists in itself. The important thing for them is that this reality will never be independent of the mind, of the consciousness of the person observing or testing it. For interpretativists, ‘there are multiple constructed realities that can be studied only holistically; inquiry into these multiple realities will inevitably diverge (each inquiry raises more questions than it answers) so that prediction and control are unlikely outcomes although some level of understanding (verstehen) can be achieved’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985: 37). Consequently, for constructivists and interpretativists, ‘reality’ (the object) is dependent on the observer (the subject). It is apprehended by the action of the subject who experiences it. We can therefore talk about a phenomenological hypothesis, as opposed to the ontological hypothesis developed by the positivists. The phenomenological hypothesis is based on the idea that a phenomenon is the internal manifestation of that which enters our consciousness. Reality cannot be known objectively – to seek objective knowledge of reality is utopian. One can only represent it, that is, construct it.

Subject-object interdependence and the rebuttal of the postulate that reality is objective and has its own essence has led interpretativist and constructivist researchers to redefine the nature of the social world.

For interpretativists and constructivists, the social world is made up of interpretations. These interpretations are constructed through actors’ ‘interactions, in contexts that will always have their own peculiarities. Interactions among actors, which enable development of an intersubjectively shared meaning, are at the root of the social construction of reality’ (Berger and Luckman, 1966).

The self-fulfilling prophecies of Watzlawick (1984) are a good illustration of the way actors can themselves construct the social world. A self-fulfilling prophecy is a prediction that verifies itself. According to Watzlawick (1984), it is a supposition that, simply by its existence, leads the stated predicted event to occur and confirms its own accuracy. The prediction proves to be accurate, not because the chain of cause and effect has been explained, nor by referring to laws of an external reality, but because of our understanding, at a particular moment, of the interactions among actors. From this, the succession of subsequent interactions is easy to foresee. Consequently, according to Watzlawick (1984), the degree to which we can predict behavior is linked not to a determinism external to the actors, but to the actors’ submission to imprisonment in an endless game that they themselves have created. In self-fulfilling prophecy, the emphasis is on interaction and the determining role of the actors in constructing reality. Such prophecies depend heavily on context. They can only be made once we understand the context of the interaction – an understanding through which we are able to learn the rules of the game.

Consequently, interpretativists and constructivists consider that individuals create their environments by their own thoughts and actions, guided by their goals. In this world where everything is possible and nothing is determined, and in which we are free to make our own choices, it has become necessary to reject determinism in favor of the intentionalist hypothesis. The knowledge produced in this way will be subjective and contextual, which has numerous research implications, as Lincoln and Guba emphasize in the case of the inter- pretativist paradigm.

To sum up, the nature of the knowledge that we can hope to produce will depend on our assumptions about the nature of reality, of the subject-object relationship and the social world we envisage (see Table 1.2).

These elements (nature of reality, nature of the subject-object link, vision of the social world) constitute reference points for researchers wishing to define the epistemological position of their research.

Table 1.3, constructed on the basis of work by Smircich (1983) and Schultz and Hatch (1996), shows clearly that the nature of the knowledge produced in the field of organizational culture depends on the researcher’s assumptions about the nature of the social world.

Their understanding of the nature of the knowable reality and the social world will indicate the path researchers must take to obtain knowledge. In a positivist framework, researchers seek to discover the laws imposed on actors. In an interpretativist framework, they seek to understand how actors construct the meaning they give to social reality. In a constructivist framework, researchers contribute to the actors’ construction of social reality.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021