Although the relevance and coherence of the initial research design have a direct influence on the quality of later research stages, this design is by no means inalterable. Problems and opportunities will arise as the research progresses, which can have an effect on the design. Meyer (1992) illustrates such evolution. His research design evolved following an event that occurred during data collection. Meyer was carrying out interviews in hospitals in the San Francisco area when doctors in the area began a general strike. This social action gave him the opportunity to turn his research into a quasi-experiment, which he did.

This section looks at a number of ways in which a design can evolve during the course of the research. We explore how to incorporate flexibility into a research approach, and how this can enable positive developments to take place as opportunities arise.

1. Design Flexibility

Thus far we have presented the various stages of research in sequential order, underlining their interdependence. It is this very interdependence which necessitates a coherent research design, with certain choices having a real effect on the later stages of research (Selltiz et al., 1976). However, this sequentiality is limited to the level of a general overview of the research process. In practice, research stages rarely follow a strictly linear progression: the research process does not unfold as a well-ordered sequence, where no stage can start before the preceding one is finished (Daft, 1983; Selltiz et al., 1976). Stages overlap, are postponed or put forward, repeated or refined according to the exigencies and opportunities of the research environment. The boundaries between them tend to become fuzzy. Two consecutive stages can share common elements, which can sometimes be dealt with simultaneously. According to Selltiz et al. (1976), in practice, research is a process in which the different components – reviewing existing works, data collection, data analysis, etc. – are undertaken simultaneously, with the researcher focusing more on one or another of these activities as time passes.

The literature review is a perfect example of this. Whatever the type of design, this referral to existing works continues throughout the entire research process. Background literature is often essential for analysis and interpretation. Further reading, or rereading past works, makes it possible to refine the interpretation of the results and even to formulate new interpretations. Moreover, since the results of the research are not necessarily those expected, analysis can lead to a refocusing of the literature review. A researcher may decide to voluntarily exclude some works he or she had included. Conversely, additional bibliographical research may need to be carried out, to explain new aspects of the question being studied. This can lead to including a group of works which, voluntarily or not, had not been explored in the beginning.

Therefore, while it is generally accepted that reading is a precondition to relevant research, it is never done once and for all. Researchers turn back to the literature frequently throughout the whole research process, the final occasion being when writing the conclusions of the research.

Some research approaches are, by nature, more iterative and more flexible than others. Generally speaking, it is frequent in case studies to acquire additional data once the analysis has begun. Several factors may justify this return to the field. A need for additional data, intended to cross-check or increase the accuracy of existing information, may appear during data analysis. Researchers can also decide to suspend data collection. Researchers can reach saturation point during the data collection phase – they may feel the need to take a step back from the field. As described by Morse (1994), it is often advisable to stop data collection and begin data analysis at this point. The principle of flexibility is at the heart of certain approaches, such as grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) where each new unit of observation is selected according to the results of analyses carried out in the preceding units. In this procedure, data collection and data analysis are carried out almost simultaneously, with frequent returns to the literature in an attempt to explain new facts that have been observed. These many iterations often result in refining the research question, and sometimes in redefining it entirely, according to observations and the opportunities that arise.

Experimentation, on the contrary, is a more sequential process. The data analysis phase begins only when all the data has been collected. Moreover, this data collection method is quite inflexible. An experiment cannot be modified while it is being carried out. Indeed, that would cast doubt on the very principle of control that constitutes the basis of the method. If difficulties arise, the researcher can simply stop the experiment in progress and start another. Between these extremes, investigation by questionnaire is not very flexible or evolving, but it is sometimes possible, should difficulties occur, to supplement missing information by calling back the respondent, or increasing a sample with a second series of inquiries. Thus, even within the framework of research based on stricter procedures, a return to the data collection stage remains possible after the beginning of data analysis.

2. Problem Areas

Whichever the approach, various problems can emerge during research, be it during pre-tests, data collection or data analysis. These problems do not necessarily imply the need to change the initial design, and it is advisable to estimate their impact before undertaking a modification of the research design. However, in the event of significant problems, a modification of the design can be necessary – even several modifications, depending on the difficulties encountered.

2.1. Pre-tests and pilot cases

The research process generally includes activities that seldom appear in proposed methodologies (Selltiz et al., 1976). Fitting in between the stages of design and data collection, pre-tests and pilot cases aim to assess the feasibility of the research through evaluating the reliability and validity of the data collection tools used, be they quantitative or qualitative. While carrying out a pre-test is invaluable for research based on a very rigid design, such as experimentation, evaluating the data collection system through pre-tests can be useful for any type of design.

Questionnaires can be ‘pre-tested’ on a small sample population, mainly to check that the wording of the questions is not ambiguous. Experimental stimuli can be similarly tested, and designs based on multiple case studies can include a preliminary stage, in which a pilot case study is carried out. This is often chosen by the researcher on the basis of favorable access conditions, and will be used to assess both the proposed data collection procedures and the type of data needed to address the research question. For a single case study, the data collection system can be pre-tested at the beginning of the collection phase. For example, researchers may try to evaluate their influence on the phenomenon under study, or test different ways of carrying out interviews.

The impact of pre-tests or pilot cases on a research project varies according to what the researcher is trying to test and the problems that are revealed. In many cases, this evaluation of the data collection system leads to reformulating or modifying the questionnaire or interview guide, without having any effect on the design. However, pre-tests and pilot cases can also reveal more fundamental problems, likely to lead to a stage of ‘reconceptualization’: new hypotheses may be defined, which will then need to be tested, or the research question itself might need to be modified. Pre-testing can even lead researchers to alter their research approach completely. A case study might be substituted for a survey if the pre-test revealed complex processes that could not be captured through a questionnaire.

2.2. Difficulties encountered during data collection

Interviewing, observing actors within an organization, or collecting documents are relatively flexible data collection methods. For example, a researcher can easily modify the course of an interview to explore a new topic raised by the respondent. If necessary, it is often possible to return to a respondent for additional information. Similarly, the method used to sort information is likely to undergo modifications during the collection process. But while collecting qualitative data is more flexible than collecting quantitative data, access to the field may be more difficult. Unexpected events during data collection can have an effect on the site chosen for the investigation – perhaps even completely calling it into question. A change in management, a modification in organizational structures, a transfer of personnel, a merger or an acquisition, or a change in shareholder structure are all likely to modify the context under study. The disturbances these events can cause may make access conditions more difficult. Respondents’ availability might decrease, and key respondents might even leave the organization. In some cases, the field may become irrelevant because of such changes, especially when it had been selected according to very precise criteria that have since disappeared.

Researchers can also find their access denied following a change in a key informant or an alteration in the management team. For example, the new managers might consider the study (approved by the previous team) inopportune. While such a case is fortunately rare, many other obstacles are likely to slow down a research project, or create specific problems of validity and reliability. Research requiring a historical approach can come up against difficulties in gathering enough data, perhaps due to the loss of documents or the destruction of archival data.

Problems of confidentiality can also arise, both outside and within the organization being studied (Ryan et al., 1991). For example, as the design evolves, the researcher may unexpectedly need to access a different department of the company. This access could be refused for reasons of confidentiality. The researcher may obtain information that would prove embarrassing for certain participants if revealed. The planned data validation procedure might then have to be modified. For example, the researcher may have planned to provide all interviewees with a summary of the information collected from each other interviewee. Such a procedure of data validation will have to be abandoned if problems of confidentiality arise.

Difficulties arise during data collection with less flexible research approaches too, using questionnaires or experiments – even if all precautions have been taken during the pre-test stage. Samples may be too small if the response rate is lower than expected or the database ill adapted. Measurement problems may not be detected during the pre-test phase, for example, because of a bias in the sample used for the pre-test. Indeed, pre-tests are sometimes carried out on a convenient sample whose elements are chosen because of their accessibility. Consequently, they can be somewhat removed from the characteristics of the population as a whole.

Selltiz et al. (1976) suggest several solutions to solve field problems. However, before deciding to modify the design, the researcher should evaluate the potential impact of the problems. If the research cannot be carried out under the ‘ideal’ conditions that had been defined initially, the difference between the ideal and the real conditions do not necessarily question the research validity. One solution is to carry out only minor modifications to the design, if any, and to specify the limits of the research. When problems are more significant, some parts of the research must be redone. This can be expensive, including in psychological terms, since the researcher has to abandon part of the work. One possibility is to find a new field in which to carry out the research. Another solution involves modifying the research design. One question can be investigated through different research approaches. For example, faced with difficulties of access to the field, research on behavior, initially based on observing actors in their organizational environment, could sometimes be reoriented towards an experimental design.

Problems encountered during data collection are not necessarily insurmountable. The research design can often be adapted, without abandoning the initial subject, even if in some cases an entirely new design has to be formulated.

2.3. Difficulties encountered during data analysis

Whatever approach is adopted, obstacles can appear during the analysis phase. These obstacles will often ultimately enrich the initial design as new elements – new data collection processes or new analyses – are included, to increase the reliability of the results or improve their interpretation.

Analysis and interpretation difficulties are frequent with qualitative research approaches. These may lead researchers to return to the field, using, for example, different data collection methods to supplement information they already have. Such new data might be analysed in the same way as the previously collected data, or it might be processed apart from the previous data. If an ethnographic approach is used, for example, a questionnaire could complement data collected by observation.

A researcher may find it impossible to formulate satisfactory conclusions from the analysed data. In a hypotheses-testing approach, survey or databases results may lack of significance, especially when the sample is too small. In this case, the conclusions will be unclear. If sample size cannot be increased, one solution is to apply another data analysis method to replace or complement those already carried out. In a hypothetico-deductive approach, the data collected may lead to rejecting the majority of, or even all, the hypotheses tested. This result constitutes in itself a contribution to the research. However, the contribution will be improved if this leads the researcher to propose a new theoretical framework (Daft, 1995). Comparing research results with existing literature, in particular in other domains, can help researchers to formulate new hypotheses and adapt the conceptual framework they use. These new proposals, which have enriched the research, may be tested later by other researchers. A qualitative approach can also produce new hypotheses. For example, research initially centered on testing hypotheses that have been deduced from existing models could be supplemented by an in-depth case study.

Obstacles confronted during the analysis stage can often result in modifying the initial research design. While this generally consists of adjusting or adding to the design, sometimes it will have to be abandoned entirely. This is the case, for example, when an ethnographic approach is replaced by an experimentation.

3. General Design Process

While an initial design can hopefully pinpoint uncertain areas, in order to avoid the emergence of problems in later stages of the research, this does not guarantee that difficulties will not arise requiring either adjustments or even more significant modifications to the design. Yet design evolution is not necessarily due to difficulties occurring during the course of research. As we saw at the beginning of this third section, this evolution can be the result of iterations and flexibility inherent to the approach. It can also be the result of opportunities arising at various stages of the research. Collected data, a first data analysis, a comment from a colleague, a new reading or an opportunity to access a new field are all means of bringing forward new ideas, hypotheses or explanatory or comprehensive models. These may lead researchers to reconsider the analysis framework, to modify the research question or even to give up the initial approach in favor of a new one that they now consider more relevant.

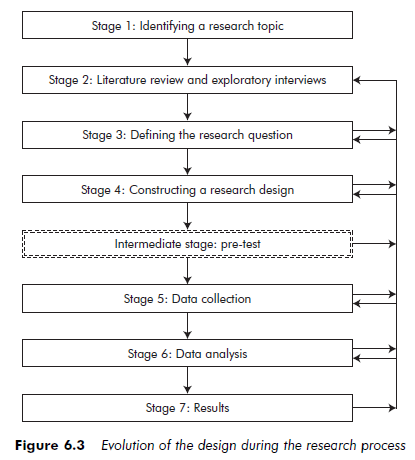

Constructing the final research design is an evolutionary process. It generally includes an amount of looping back and repeating stages, both when putting together the initial design and later on in the research (see Figure 6.3).

The actual construction of a research design is thus a complex, evolving, uncertain process. A sufficient level of residual uncertainty in a research design determines its interest and quality (Daft, 1983). This is why, according to Daft, research is based more on expertise than knowledge. This skill is acquired through a learning process, based on experience and frequenting the field. Research quality depends largely on how well prepared the researcher is. Researchers, in order to succeed, must possess certain qualities and dispositions: wisdom and expertise during data collection; perseverance and meticulousness in the analysis phase; along with a solid theoretical training and a taste for uncertainty (Morse, 1994; Daft, 1983; 1995).

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

Thank you for the good writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it.

Look advanced to far added agreeable from you!

However, how can we communicate?

Awesome post.

Everything is very open with a very clear explanation of the

challenges. It was truly informative. Your site is very helpful.

Thanks for sharing!

I was able to find good information from your blog articles.

Pretty! This has been an extremely wonderful article.

Thank you for providing this info.