Clearly, the data collected should be as accurate as possible. However, complete accuracy is almost impossible to obtain in surveys where respondents are asked to report their behaviour or their attitudes.

Many problems arise because of problems within the questionnaire itself. These can include:

- ambiguity in the question;

- order effects between questions;

- order effects within a question;

- inadequate response codes;

- wrong questions asked because of poor routeing.

Some of the problems outside the direct control of the researcher in trying to collect accurate and unbiased data include:

- questions asked inaccurately by the interviewer;

- failure of the respondent to understand the question;

- failure of the interviewer to record the reply accurately or completely;

- failure of the questionnaire to record the reply accurately or completely;

- inattention to the interview because of respondent boredom and fatigue;

- mistakes made by the interviewer because of boredom and fatigue;

- desire by the respondent to answer a different question to the one asked;

- inaccuracy of memory regarding behaviour;

- inaccuracy of memory regarding time periods (telescoping);

- asking respondents to describe attitudes on subjects for which they hold no conscious attitude;

- respondents lying as an act of defiance;

- respondents wishing to impress the interviewer;

- respondents not willing to admit their attitudes or behaviour either consciously or subconsciously;

- respondents trying to influence the outcome of the study and giving answers that they believe will lead to a particular conclusion.

Some of the main biases are analysed by Kalton and Schuman (1982).

Ways in which the questionnaire and questions can be written and structured to minimize the effects of these phenomena will be covered in later chapters on questionnaire construction and question writing. In this chapter we will consider the problems that each of these causes, with the exception of the last three, which are part of a subject known as ‘social desirability bias’. This, and the ways in which it can be countered, is a sufficiently important subject to warrant its own chapter, Chapter 12.

1. Questions asked inaccurately by the interviewer

It is not uncommon to hear an interviewer paraphrase a question in order to make it sound more conversational. Anyone who has written a questionnaire and then used it to interview a number of people is likely to have found themselves doing it, as they realize that a question that looks accurate on paper often sounds stilted when spoken. Where the interviewer is the same person as the questionnaire writer it may be permissible to amend the wording as the interview proceeds. The author knows the intent of the question and will take care not to alter the sense or meaning of it.

However, when someone else paraphrases it, it is likely that some aspect of the question will be changed, and the response will be different to the one that would have been obtained from the original question. Good interviewer training will instil into the interviewer that the wording on the questionnaire is to be kept to. If, after that training, the interviewer feels the need to alter the wording, then it is a sign of a poorly written question. The role of the interviewer is to hold a conversation with the respondent on behalf of the researcher. The question writer must ensure that this is what happens.

Interviewers can ask questions wrongly because they do not understand them themselves, or because they are too long, and particularly if they involve many sub-clauses. Well-trained interviewers will always make themselves familiar with the questionnaire and the questions before starting the first interview, but if questions are too long and complex, mistakes will happen.

With some business-to-business interviews, the interviewer may not understand the terminology used. A thorough briefing of the interviewers should be carried out and it may be advisable to provide a glossary of terms that respondents may use when giving open-ended verbatim comments. These can be made available on-screen or on paper. They may also be of benefit to coders and editors at the analysis stage of the survey.

2. Failure of the respondent to understand the question

If the interviewer fails to understand a question, then it is reasonable to expect that respondents will too. Again, long and complex questions will be the most likely to cause problems, or questions that use words that are not part of the respondent’s everyday vocabulary.

Respondents may fail to understand a question because it is not in their competence to answer it. Thus it would be a mistake to ask people what they think is a fair price for certain high-specification audio equipment if they do not own any, have no intention of owning any and do not understand the implications of the high-specification features. Some respondents may recognize that they do not have the knowledge to answer the question and say so, in which case they will be recorded as ‘Don’t know’.

Others, though, will believe that they do understand the implications, and provide an answer, but one based on a failure to understand the question.

Ambiguity in a question can mean that the respondent cannot understand what is being asked or understands a different question from the one intended.

3. Failure of the interviewer to record the reply accurately or completely

Interviewers record responses inaccurately in many ways. They may simply mishear the response. This is particularly likely to happen where, on a paper questionnaire, there is a long and complex routeing instruction following a question. The interviewer’s attention may well be divided between listening to the respondent’s answer and determining which question should be asked next. The interviewer may be trying to maintain the flow of the interview, and not have it interrupted by a lengthy wait whilst the subsequent question is found, but this is bound to increase the risk of mishearing the answer. This is not an issue with computer-based questionnaires where routeing to the next question is automatic.

With open-ended (verbatim) questions, interviewers may not record everything that is said. There is a temptation to paraphrase and precis the response again in order to keep the interview flowing and so as not to make the respondent wait whilst the full verbatim is recorded.

It is common to provide a list of pre-codes as possible answers to an open question. Interviewers scan the list and code the answer that most closely matches the response given. This is open to error on two counts. First, none of the answers may match exactly what the respondent has said. The interviewer (or respondent, if self-completion) then has the choice of taking the one that is closest to the given response or there is frequently an option to write in verbatim responses that have not been anticipated. There is a strong temptation to make the given response match one of the pre-coded answers, thus inaccurately recording the true response. To minimize the chances of this happening, the pre-coded list may contain similar, but crucially different, answers. The danger then is that when the interviewer (or respondent) scans the list he or she sees only the answer that is close to but different from the given response and codes that as being ‘near enough’. In many ways, this is a worse outcome, as it misleads the researcher.

4. Failure of the questionnaire to record the reply accurately or completely

The main failure of questionnaires in this respect is in not providing a comprehensive list of possible answers as pre-codes for interviewers and respondents to record the response accurately. The response to the question ‘Do you like eating pizza?’ sounds as if it should be a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’, but respondents may wish to qualify the answer depending on whether it is home-made or shop-bought, the toppings or the occasion. If they are unable to do so, an answer of ‘Don’t know’ may be recorded. Whatever is recorded is not the complete response.

It is common to see a question such as ‘How often do you visit the cinema?’ given the possible answers:

More than once a week.

Once a week.

Once a month.

Once every three months.

Less often than once every three months.

Such an answer list cannot accurately record the behaviour of someone who went to the cinema twice in the last week and not at all in the three months before that. Either the respondent or the interviewer has to decide what is the least inaccurate response.

This type of questionnaire failure, leading to inaccurately recorded data, has, however, become accepted for many types of survey, principally because the alternative of allowing for all possible responses would be too complicated to process and analyse.

5. Inattention to the interview because of respondent boredom and fatigue

Response mistakes made by respondents because of failure to understand the question or to give sufficient thought to their response are exacerbated when they become tired of or bored by the interview process.

When that happens, respondents will adopt strategies designed to get them to the end of the interview as quickly as possible and with as little thought or effort as possible. Thus with repeated questions, such as rating scales, they will often go into a pattern of response that bears little or no relationship to their actual answers. With self-completion rating scales this strategy will often be something like marking all the boxes that are second from the right-hand side of the page. This strategy is easily spotted by the analyst and dealt with, but where a random strategy is adopted it may be impossible to spot.

With behavioural questions less thought is given to the responses as fatigue sets in. Sometimes any answer will be given just to be able to proceed to the next question. Towards the end of an interview answers are sometimes given that contradict those given earlier, because of boredom and fatigue.

The point at which boredom and fatigue will set in can be difficult to judge beforehand. It will depend on the level of interest of the respondent in the subject matter and the skill of the questionnaire writer in providing a varied and interesting experience.

No matter what the subject, interest is retained longer if the interview experience is itself interesting. Few people think that they could talk for an hour and a half about tomato ketchup. However, a skilled qualitative researcher can keep the interest of a group discussion or focus group on any subject for that length of time and have the participants thank them afterwards for an interesting time. It is more difficult to achieve that in a structured questionnaire survey, but that should be the aim of all questionnaire writers.

Few structured interviews, however, can retain the interest of any respondent for as long as 90 minutes (with the possible exception of cars or a hobby subject), and a realistic expectation for most topics is that fatigue will set in after about 30 minutes for most respondents on most subjects.

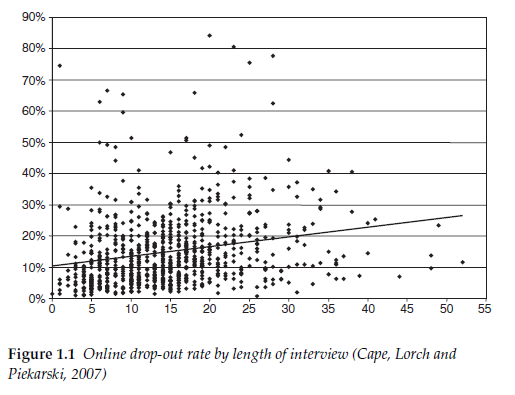

With interviewer-administered surveys respondents will often continue to the end, encouraged and cajoled by the interviewer for whom only a completed interview counts. Online, respondents who are bored or fatigued simply log off, even if they lose the financial or other incentives to complete the questionnaire. Figure 1.1, taken from Cape, Lorch and Piekarski (2007), shows how drop out is a function of length of questionnaire, as respondents become bored and fatigued. It can be seen that in a large number of projects more than 20 per cent drop out. With an interviewer-administered interview, many of these would have continued reluctantly to the end, providing potentially unreliable data.

Figure 1.1 also demonstrates that length of the questionnaire is not the only factor in the decision to drop out. Cape, Lorch and Piekarski attribute this largely to the quality of the questionnaire design. This shows that with poor questionnaire design, fatigue is likely to set in earlier and results become unreliable sooner in the interview. The importance of good questionnaire design in gaining good quality data is demonstrated.

6. Mistakes made by the interviewer because of boredom and fatigue

A long and tedious interview affects not only the respondent but also the interviewer. Like everybody else, interviewers make mistakes. Whether the interview is on the telephone or face to face, responses can be misheard, or a wrong code recorded. And these errors become more frequent if the interviewer is tired of or bored with the interview. An interview that is tedious for the respondent is also tedious for the interviewer. This can be made worse for the interviewer by the embarrassment felt in being responsible for boring the respondent. The interviewer responds by reading the questions more quickly, leading to an increase in the number of errors of misunderstanding as well as recording errors on the part of the interviewer.

This, however, is not a problem confined to techniques using interviewers. With self-completion surveys, where there is no interviewer, a long and tedious questionnaire simply results in respondents failing to finish the interview. This means that the response rate falls and the sample of completed interviews is less representative of the population than it could have been.

7. Desire by the respondent to answer a different question to the one asked

Sometimes respondents will ‘interpret’ the question in a way that fits their circumstances. When asked how often they go to the cinema, respondents who see films at a club may choose to include those occasions in their response because that is the closest they come to going to a cinema. If the interviewer is made aware of this, then a note can be made and a decision taken later by the analyst as to whether to include this or not. However, often the interviewer will not be told, and, with most computer-aided systems, including Web-based surveys, there is no mechanism provided for respondents to alert the researcher to their interpretation of the question.

8. Inaccuracy of memory regarding behaviour

Memory is notoriously unreliable regarding past behaviour. It is invariably more accurate for respondents to record their behaviour as it happens, using a diary or similar technique. However, the cost or feasibility of that type of approach often rules it out, and the behavioural data that are collected in most studies are behaviour as reported by memory.

The accuracy of recall will depend on many factors, including the recency, size and significance to the individual of the behaviour in question. Most people will be able to name the bank they use, but will be less reliable about which brand of tinned sardines they last bought. Frequently what is reported is an impression of behaviour, the respondents’ beliefs about what they do, rather than an accurate recording of what they have done. Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski (2000) list the following reasons for memory failure by respondents to surveys:

There are several major sources of memory failure:

- Respondents may not have taken in the critical information in the first place;

- They may be unwilling to go through the work of retrieving it;

- Even if they do try, they may be unable to retrieve the event itself, but only generic information about events of that type;

- They may retrieve only partial information about the event and, as a result, fail to report it; or

- They may recall erroneous information about the event, including incorrect inferences incorporated into the representation of the event.

Researchers are generally aware that recall information can be unreliable. However, what is sometimes overlooked is the bias introduced into the responses by the third of the sources of memory failure listed above. When respondents generalize about types of events they will tend to report not only what they believe that they do, but also what they believe that they do most of the time. Even if what they say is accurate, minority behaviour will tend to be unreported.

9. Inaccuracy of memory regarding time periods (telescoping)

Particularly notorious is the accuracy of memory related to time. Respondents will tend to report that an event occurred more recently than it actually did. Researchers and psychologists have long been aware of this phenomenon. The first important theory of telescoping was proposed by Sudman and Bradburn (1973). They wrote: ‘There are two kinds of memory error that sometimes operate in opposite directions. The first is forgetting an episode entirely… The second kind of error is compression (telescoping) where the event is remembered as occurring more recently than it did.’

Thus, asked to recall events that occurred in the last three months, respondents will tend to include events that occurred in what feels like the last three months but is usually a longer period. Additional events are therefore ‘imported’ into that period and mistakenly reported (forward telescoping). In contrast, other events are forgotten or thought to have occurred longer ago than they really did (backward telescoping) and are therefore not reported. The extent to which telescoping occurs will depend on the importance of the event to the respondent and the time period asked about.

A technique suggested to help respondents (Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski, 2000) in interviewer-administered surveys is to extend the question beyond what is absolutely necessary in order to give the respondent more time to think before they feel obliged to provide an answer. This may be particularly the case with telephone interviewing, where silences can be awkward and the respondent may avoid them by answering before they have fully thought it through.

10. Asking respondents to describe attitudes on subjects for which they hold no conscious attitude

Researchers often ask respondents to reveal their attitudes about a range of subjects that the respondents have never before given conscious thought to. Many respondents may feel that they have an attitude

towards issues such as street crime and how to deal with it, but few will have consciously thought about the issues surrounding the role of pizza in their lives. Questionnaires frequently present respondents with a bank of attitude statements on subjects that, while of importance to the manufacturer, are very low down on the respondent’s list of burning issues. Studies have shown that the data reported are more stable over time where respondents are not given time to think about their attitudes but are asked to respond quickly to each statement (Tourangeau, Rips and Rasinski, 2000). Attitudinal questions will often include an instruction to respondents to give their first reaction and not to spend time considering each statement.

11. Respondents lying as an act of defiance

Some people see market research as a tool of ‘big business’, and some people hold negative attitudes towards multinational corporations. They are held responsible by these people for many of the world’s problems from the globalization of products and services to political instability. Confronted with a market research interview, these people may see an opportunity to disrupt and distort the information held by big business, even if only in a small way.

Consequently, these people will appear to cooperate, but will deliberately lie about their behaviour and attitudes in the expectation that somehow they will be helping to disrupt the commissioning organization’s business. Sometimes they can be spotted at the analysis stage because of inconsistencies in their responses, which have been made up as they go along, but this may not always be the case.

Such people are probably few in number, and the tendency is to ignore them in the belief that they will cancel each other out, with one pizza- eater denying that he or she eats pizza counterbalanced by a non-pizza- eater claiming to be an avid consumer. Opt-in media such as web-based panels are particularly prone to this type of activity, as they are relatively easy to target.

The questionnaire writer has much to consider. The overriding objective is to achieve the most accurate data that will satisfy the research objectives and the business objectives, by avoiding all of these reasons for inaccuracy, at the same time as meeting the needs of all the various stakeholders in the questionnaire.

Source: Brace Ian (2018), Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research, Kogan Page; 4th edition.

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021