The key benefits of having an interviewer administer the questionnaire are:

- Queries about the meaning of a question can be dealt with.

- A misunderstood question may be corrected.

- Respondents can be encouraged to provide deeper responses to open questions.

Sometimes a question can be unintentionally ambiguous. Although this should have been spotted and corrected before the questionnaire was finalized, it is possible for such questions to slip through. If respondents cannot answer because of the ambiguity, then they are able to ask the interviewer for clarification. Interviewers, though, must be careful not to lead respondents to a particular answer when giving their clarification, and should report back to the researcher that clarification was required.

Interviewers can sometimes spot that respondents have misunderstood the question by the response that they give, which may be inconsistent with previous answers, or simply inconsistent with what the interviewer already knows (or suspects) about the respondents and their situation. Such an inconsistency can be challenged, the question repeated and the response corrected if necessary.

An interviewer administering the questionnaire thus gives an opportunity for mistakes of the questionnaire writer to be corrected, but it also gives the questionnaire writer an opportunity to probe for information on open questions. At the simplest level, a series of non-directive probes (eg ‘What else?’) can be used to extract as much information as possible from the respondent. If a bland and unhelpful answer is anticipated, the interviewer can be specifically asked to obtain further clarification. For example, the question ‘Why did you buy the item from that shop in particular?’ is likely to get the answer ‘Because it was convenient.’ An interviewer can be given an instruction not to accept an answer that only mentions convenience, and the questionnaire will supply the probe ‘What do you mean by convenient?’

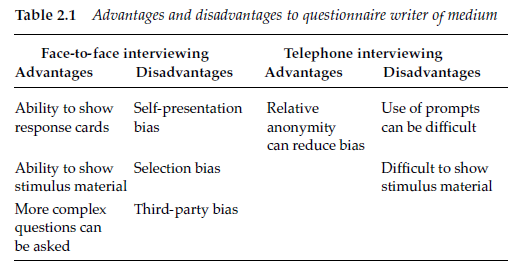

Interviewer-administered questionnaires can be used in either face-to- face interviews or in telephone interviews. Each of these has its advantages and disadvantages in questionnaire writing. The choice of which is to be used will have been strongly influenced by the overall survey design, but the appropriateness of the medium to the questions to be asked will also play a part (see Table 2.1).

1. Face-to-face

In the UK, face-to-face interviewing has been the dominant mode of data collection for many years. Although this dominance has been reduced by telephone interviewing and more recently by internet-based interviewing, the majority of market research interviewing in the UK and much of Europe is still face-to-face interviewer-administered. In the USA, face-to-face interviewing has never accounted for the same high proportion of interviews.

Many of the advantages of telephone interviewing are associated with access to respondents, survey control and speed. These do not relate to questionnaire design but can be deciding factors in the survey design.

2. Advantages of face-to-face interviewing

One clear advantage of face-to-face interviewing is the ability to show prompt cards easily to respondents. These cards can be used in questions where prompted awareness or recognition of names is required, where respondents are being asked to select their answer from a scale, or where it is desirable to prompt with a list of possible responses.

The ability to show things also means that products and ideas can be shown to respondents for their reactions. This is obviously important for evaluating any product or advertising, or where reaction is required to new ideas or concepts for products or advertising. Frequently, surveys evaluating products and concepts will be carried out in a central location. This facilitates:

- transportation of the product – particularly if it is something bulky like a washing machine;

- demonstration of the product – making sure it is cooked or served correctly;

- security of a concept or a new product that might be of significant interest to a competitor.

Where the product or concept is portable, or where the product is left with the respondent to be tried, then in-home face-to-face interviewing is often preferred.

3. Face-to-face CAPI

CAPI (computer-assisted personal interviewing) is the use of a portable computer that provides the questions and pre-codes on the screen. The computers can be either tablet computers with a touch screen for responses to be recorded by touching a ‘pen’ on to the screen, or laptop personal computers where answers are recorded by clicking the cursor on the appropriate box. Laptops may have multimedia capabilities. In central locations, desktop personal computers may be used. Personal digital assistants (PDAs) can be used in some circumstances where the number of questions is relatively small. (PDAs have also been used successfully as a self-completion medium.) Pocket PCs connected through a local WiFi network are now also used in appropriate circumstances.

Whichever type of computer is used, it can either provide the interviewer with a questionnaire and means of recording responses, or allow the respondent to participate in the interview through self-completion of part or all of the questionnaire. Either way, it brings a number of advantages for the questionnaire writer. Principal amongst these is the ability to include complex routeing between questions. Thus, the question that is asked of the respondent can be determined by a combination of answers from a number of previous questions. Such complex routeing would have resulted in a significant level of error if the interviewer had had to determine which question was to be asked.

Similarly, with CAPI, calculations can be programmed into the questionnaire, which it would not have been possible to ask the interviewer to carry out without risking a high level of error. Thus an estimate of a household’s annual consumption of a grocery product can be calculated. This would be impossible for respondents to estimate accurately. However, they may be able to make more accurate estimates of shortterm consumption for each member of the family, from which total household consumption can be calculated. In business-to-business interviewing, volumes of consumption or output can be summed either as a total or within predetermined categories, for the interviewer to read back to the respondent to check the accuracy. This information can be used both as inputs to future questions and for question routeing.

The questionnaire writer has to worry less about the layout of the questionnaire with CAPI than with paper questionnaires. Eliminating many interviewer instructions as well as providing the means of recording precoded or numerical data makes this part of the questionnaire writer’s task easier.

With pre-coded prompted questions, CAPI can randomize or rotate the order in which the response list is presented to the respondent on-screen. Some researchers prefer to use prompt lists on cards that can be handed to and easily read by the respondent. However, where the respondent is asked to read response lists from the screen, then randomization and rotation of response lists can present a significant advantage (see Chapter 7).

The combination of being able to make calculations and to randomize response lists has led to the development of some complex techniques such as adaptive conjoint analysis. With this technique, the responses to questions asked at the beginning of the sequence are used to construct scenarios shown at later questions where the respondent is asked to provide preferences between them. Even the number of scenarios asked about is determined by the respondent’s pattern of answers. Whilst this is theoretically possible with paper questionnaires (and a lot of show cards), the adaptive conjoint questionnaire is made easy to administer with the use of a computerized questionnaire.

Multimedia CAPI provides the questionnaire writer with more opportunities to present colour images, moving images and sound. Thus television or cinema advertisements can be played as stimuli either for recognition or for evaluation. When evaluating television or cinema advertisements on CAPI, care must be taken to ensure that all parties involved in implementing the findings are happy with the quality of the reproduction of the ad on the computer screen.

CAPI also presents self-completion options such as having icons or representations of brands that can be moved on the screen and placed in appropriate response boxes by the respondent.

Packs can be displayed, and supermarket shelves simulated. This creates opportunities to simulate a presentation, as it would appear in a store, with different numbers of facings for different products, as an attempt to reproduce better the actual in-store choice situation.

Three-dimensional pack simulations can be shown and rotated by respondents, whilst they are asked questions about the simulations.

Electronic questionnaires thus provide the possibility of showing improved stimuli; of offering new ways of measuring consumer response; and of making the process more interesting and involving for the respondent.

4. Disadvantages of face-to-face interviewing

The main disadvantage of face-to-face interviewing is generally the cost of obtaining a sufficiently representative sample of the survey population. However, that is an issue of survey design and does not relate directly to the interview process.

The accuracy of the data can be influenced by the interaction between interviewer and respondent. Carefully chosen and well- trained interviewers are essential if the quality of the data is to be maximized. The biases that can be introduced by the presence of the interviewer, and the inaccuracies that can be caused if the interviewers fail to ask questions and record responses as they should, have already been discussed in Chapter 1. How to minimize these is part of the skill of the questionnaire writer.

5. Telephone-administered questionnaires

5.1. Advantages of telephone interviewing

Most of the advantages enjoyed by telephone interviewing are to the benefit of the survey design rather than to the questionnaire design. Thus there are efficiencies in cost and speed, particularly where the sample is geographically dispersed, or where, as often happens in business-to-busi- ness surveys, the respondents are prepared to talk on the telephone but not to have someone visit them.

One advantage for data accuracy is that the telephone as a medium gives more anonymity to the respondents in respect of their relationship to the interviewer. This can help to diminish some of the bias that can occur as a result of respondents trying to impress or face-save in front of interviewers (see Chapter 12). It is also the experience of many researchers that respondents are more prepared to discuss sensitive subjects such as health on the telephone than face to face with an interviewer. Fuller responses are achieved to open questions, and they are more likely to be honest because the interviewer is not physically present with the respondent. Telephone interviewing thus becomes the medium of choice for interviews where there is a need for an interviewer-administered interview, coupled with a sensitive subject matter.

Computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) brings many of the same advantages to this medium as CAPI does to face-to-face interviewing. These include an ability to include complex routeing and calculations within the interview, and the automatic randomization or rotation of question order and of prompt lists within questions.

5.2. Disadvantages of telephone interviewing

From the point of view of the questionnaire writer, telephone interviewing has a number of disadvantages.

First, there is limited ability to show material such as prompt lists or stimuli. However, where the list is short it can be read out by the interviewer and remembered by the respondents.

When it is straightforward for the respondents to understand, they can hold the question and answer in their head until the time comes for them to respond. It is important that the interviewer reaches the end of the options before the respondent answers, so that the complete list of possible responses is read out.

For longer lists of response options, or repeated lists such as scales, respondents can be asked to write them down.

The inability to show material such as concepts or advertising is a drawback to telephone interviewing. Radio ads or the soundtrack from television ads can be played over the telephone as a prompt for recognition. Care must be taken to distinguish responses that arise because of the quality of the recording as heard by the respondent, which can be variable, from those relating to content. Other ways must be sought, though, for visual material.

It is possible to mail material to respondents for them to look at during the interview. This creates a lengthy and more expensive process. The respondents have to be recruited and agreement obtained in an initial interview; the material then has to be sent; the main interview can then be carried out once the material has arrived.

It may be desirable for respondents not to see the material before a certain point in the interview. In that case, the initial contact would complete the interview up until that point, when respondents would be asked permission for the researcher to send them material and to call them again to complete the interview. This procedure runs the risk of a high proportion of respondents refusing the researcher permission to send the material. There will also be a proportion of respondents who will have received the material but whom it will be impossible to recontact. This has implications for over-sampling and hence cost.

With some populations, it is possible to speed up this process. In busi- ness-to-business studies, it is now common to e-mail material to respondents. This means that the gap between the first and second contacts or parts of the interview can be reduced to minutes. By reducing that period, fewer respondents are lost between the two stages. Alternatively, the material can be faxed, but the quality of reproduction is generally significantly less, and monochrome.

A possible method of showing material, particularly in business-to- business surveys, is to ask the respondent to log on to a website where the material is displayed. The respondent can log on whilst the interviewer continues to talk on the telephone, so there is no loss of continuity in the interview. This is more difficult for consumer surveys because of households that have one line for both telephone and internet connection, and cannot use both at the same time. The increase in the use of broadband, though, makes this a more viable option for consumer surveys.

Interviews started on the telephone can be continued on the internet, by asking the respondent to log on to a website that contains the remainder of the questionnaire. There is an inevitable loss of numbers, however, because control passes to the respondents, some of whom will never log on to the website and so will not complete the interview.

Source: Brace Ian (2018), Questionnaire Design: How to Plan, Structure and Write Survey Material for Effective Market Research, Kogan Page; 4th edition.

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021

20 Aug 2021