1. The Classical Tradition

To summarise in a few lines the views of a range of writers spanning more than a century from the time of Adam Smith onwards is clearly a hazardous undertaking and one which is liable to result in severe distortions to the work of some economists. As a generalisation, however, the classical tradition, at least in England, did not offer a very sophisticated account of the entrepreneur. Indeed this state of affairs has continued in the neoclassical analysis of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries and for substantially similar reasons. Both traditions are concerned primarily with the analysis of the establishment of ‘natural’ or as we would now say ‘equilibrium’ prices. The emphasis on the final state rather than the process of getting there inevitably diverts attention from the distinctive contribution of the entrepreneur. Classical analysis recognised the role of superintendence and organisation in economic life; and, in the conditions prevailing in the late eighteenth century, the provider of capital and the organiser of production would usually be the same person. The result was a tendency to muddle together some sources of income and to reduce the significance of others. Thus the English classical writers, including Smith, Ricardo and Mill3, used the word ‘profit’ to describe the total return to the provider of capital even though this included elements which might more properly be termed ‘wages of management’, ‘interest on capital’, ‘monopoly rents’, ‘windfalls’ and so forth.

It is to the French classical tradition we must look for the origins of the idea that profit is a type of income quite distinct from that received by capital and that it goes to the entrepreneur. The early French contribution in this field is perhaps appropriately reflected in the fact that English economists have come to use the French word ‘entrepreneur’ rather than any English equivalent such as the term ‘venturer’. J.B. Say4, building on the ideas of Cantillon5, insisted that profit was a quite separate category of income from interest, thus establishing the major distinction between English and French classical schools in this area. He did not, however, emphasise as did Cantillon the importance of risk, but initially viewed profit as a wage accruing to the organiser of production. Within the French school, Knight (1921) in his review of theories of profit (p. 25) singles out Courcelle-Seneuil6 as the contributor who most clearly argued that profit was a reward for the assumption of risk and was not in any sense a wage.

Mention should also be made of the German, and especially Von Thünen’s, contribution. Von Thünen7 is most well known for his work on transport costs, land rents and the consequent spatial pattern of agricultural land-use around a city. In the development of this analysis, Von Thünen, who is said to have made extensive use of the financial records of his own estates, defines profit as a residual after the expenses of interest, insurance, and the wages of management have been met. By seeing profit as essentially a return for bearing uninsurable risks, Von Thünen was a close forerunner of Knight.

2. Knight

Knight (1921) developed and elaborated the view that entrepreneurs receive a return for bearing uncertainty. His major criticism of theory up to that date was that even those who appreciated the importance of uncertainty were unclear about its nature and implications. One view, for example, was that profit arose from the fact of continuous change and development over time. Knight did not dispute that radical and less radical changes occurred continuously and that these could give rise to uncertainty and hence to profits, but he insisted that change per se was not the issue. If, for example, changes occurred, the consequences of which were entirely foreseeable, no profits would be generated. Perfectly foreseen changes were compatible with a state of ‘equilibrium’ in which no profits would appear. This type of equilibrium is now often referred to as a ‘Hayekian’ equilibrium.8 Change occurs, but, because it is perfectly foreseen, no expectations are ever disappointed. A famous example is that of an approaching meteorite, the impact of which will occasion many changes but all of which may be calculated perfectly accurately (fire damage, loss of crops and buildings, and so on). The actual collision of the meteorite with the earth will then produce no profits, since the prices of resources have long since adjusted to the certainty of the impact and nothing unforeseen has occurred. Correct expectations, however, are critical to this result. No change is compatible with profits and losses if change is confidently expected. If contrary to all known laws of physics the meteorite suddenly veers away from the earth and disappears into outer space, people will have to adjust to this unexpected continuation of the status quo, expectations will have been disappointed and profits and losses will appear.

According to Knight, therefore, it is not change but uncertainty and the possibility of incorrect expectations which give rise to profit. Further, the term uncertainty is used by Knight only to describe circumstances in which reliable probability values cannot be attached to possible future outcomes. Where future events can be assigned probabilities, Knight uses the term ‘risk’ to describe the situation, and argues that the existence of insurance markets will often enable people to avoid such risk.9 True uncertainty cannot be avoided by paying an insurance premium. Important consequences follow from the recognition that much of economic life represents a response to the existence of uncertainty. As Knight puts it: ‘With Uncertainty present doing things, the actual execution of activity becomes in a real sense a secondary part of life; the primary problem or function is deciding what to do and how to do it’ (p. 268).

This ‘primary function’ is the entrepreneurial function. The job of deciding how various objectives are to be achieved and of predicting what objectives are worth achieving devolves on the entrepreneur, a specialist who is prepared to bear the costs of uncertainty. ‘The confident and venturesome assume the risk or insure the doubtful and timid by guaranteeing to the latter a specified income in return for an assignment of the actual result’ (pp. 269-70).

It is not clear from this that the confident and venturesome should employ the doubtful and timid, or that the entrepreneur should own and organise ‘a firm’, although Knight appears to have thought that this necessarily follows. This point will be taken up later on. For present purposes, however, the main result of Knight’s analysis is that the entrepreneur’s function is to make judgements about the uncertain future, and the reward associated with this function ‘profit’ is a return to uncertainty bearing. ‘It is our imperfect knowledge of the future … which is crucial for the understanding of our problem’ (p. 198).

This ‘Knightian’ view of the entrepreneur has a powerful intuitive appeal. Clearly the exercise of entrepreneurship is usually associated with uncertainty bearing and has something to do with imperfect knowledge, but there are equally powerful objections to it. As Schumpeter emphasised (1954, p. 556) if a person is to make a profit from uncertain turns of events, that person will do so as the owner of some marketable resource. Thus, uncertainty is borne by resource owners who have to accept the consequences for the value on the market of their resources of unexpected change. If we are prepared to define resource owners as ‘capitalists’ (that is, we suppress the distinctions between land, natural resources, buildings, physical and human capital) then uninsurable risks must be borne by capitalists. It may be objected that the entrepreneur may borrow from the capitalist at a fixed interest and that, if so, the entrepreneur not the capitalist bears the risk, but in this case, if the entrepreneur has no independent resources, failure of the enterprise must mean default on the loan and the capitalist is an uncertainty bearer. Where the entrepreneur has other resources which permit repayment of the debt in the event of failure, clearly the entrepreneur bears the uncertainty but only in so far as he or she is also a capitalist.

If uninsurable risk is borne by resource owners, what becomes of the distinctive contribution of ‘the entrepreneur’? Modern analysis of the entrepreneur reverts to and develops Say’s insight that the organisation of production, the combining together of resource inputs, requires skills of a different order than those of routine labour. Knights’ ‘primary function’ of ‘deciding what to do and how to do it’ is indeed an entrepreneurial activity, but it is conceptually a quite separate activity from bearing uninsurable risks, even though the latter may be associated with it. Recent theory therefore emphasises that the entrepreneur does not merely put up with the consequences of imperfect knowledge, but rather reaps the rewards of discovering and using new knowledge. The English tradition, in which industry appears to ‘run itself’ using inputs of capital and labour in an apparently routine and ‘mindless’ fashion, failed to recognise the importance of the coordinator; the person who decides how and what things shall be done as distinct from the person who merely ensures that they are done. In the next section a more careful elaboration of this view of the entrepreneur is attempted using the work of the most influential modern theorist in the subject, Israel Kirzner.

3. Kirzner

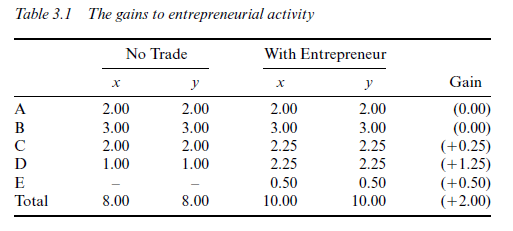

In Chapter 1 we spent some time on the elementary task of showing how a community of four individuals (A, B, C and D) could gain through specialisation and exchange. Each person, we assumed, faced different ‘production possibilities’. If each remained independent and isolated, their consumption patterns would be those of Table 1.1. Total output would be eight units of x and eight units of y. Specialisation, it was found, enabled total output to rise to ten units of x and ten units of y. Agreements to specialise in the appropriate way and distribute the output as in Tables 1.4 and 1.5 represented various ‘solutions’ to the exchange game (the ‘core’). We further saw that the establishment of appropriate prices for x and y would induce people to specialise and exchange their output on the market, and that the final position would be equivalent to a ‘core’ solution. At each stage it was emphasised that the theory as presented did not provide a persuasive account of the exchange process. ‘Core’ solutions could be calculated and equilibrium prices deduced once all the information necessary had been acquired, but there was only a limited discussion of how and to whom this information is made available.

In Edgeworth’s bargaining approach, the ‘core’ solution emerges after a process of haggling involving all the contractors in the market. In Walras’s ‘tatônnement’, the solution emerges from a trial and error sequence of price-setting by the auctioneer. In both cases it is assumed that no final decisions concerning the allocation of resources are made until the bargaining or tatônnement processes are completed. As we have seen, this is paradoxical, for it effectively implies that the information problem has to be completely solved before the stage of actual resource allocation can begin, and yet this solution of the information problem apparently requires no resources itself and hence involves no opportunity costs. These two ideas that contractors in the market must all be fully informed before anything of consequence can happen, and that the achievement of this state of full information does not in itself imply that anything of consequence has already happened, should not be rejected simply on the grounds that they are ‘unrealistic’. Within the framework of general equilibrium theory, and given the objectives and purposes of that theory, they may be perfectly defensible. Further, it is by considering the conditions imposed by the requirements of general equilibrium that the role of the entrepreneur is perhaps most easily appreciated.10

The entrepreneur is central to the process by which contractors come to perceive the opportunities presented by specialisation and exchange. Clearly, if everyone already knows the production-possibility curves and preferences of each contractor, and if everyone is a rational, calculating, individual, one of the suggested solutions of Tables 1.4 and 1.5 will be adopted, but if each person is only partially informed, the acquisition of knowledge about potential gains from exchange becomes the pivotal economic problem. It is at this point that the ‘Austrian’ tradition in economic theory, here represented mainly by the work of Kirzner, emphasises the role of the entrepreneur. Essentially, an entrepreneur is any person who is ‘alert’ to hitherto unexploited possibilities for exchange. Spotting such possibilities enables the entrepreneur to benefit by acting as the ‘middleman’ who effects the change.

3.1. The entrepreneur as a ‘middleman’

Consider once more the four individuals in Chapter 1. The production possibilities facing each were assumed to be:

A: 10 – 4x=y

B: 12 – 3x=y

C: 6 — 2x=y

D: 3 — x = 2y.

Suppose now that another individual (an entrepreneur E) turns up on the scene (there is yet another shipwreck). This individual is washed up with no resources to his or her name but, being alert to new opportunities, s/he rapidly observes that the four inhabitants s/he meets would be much better off if they specialised along the lines we have already discussed and thus coordinated their activities. It will be recalled that the ‘no trade’ consumption pattern was as shown in the left-hand side of Table 3.1. Imagine that E first contacts A and persuades A to provide him/her with eight units of y in exchange for two units of x. Person A will just be prepared to do this since by specialising in y production (ten units) and accepting E’s offer, his or her final consumption level of two units of each commodity will be unchanged. E then approaches person B and suggests that the latter should provide one unit of x in exchange for three units of y. Once more, if person B specialises in x production (four units) and accepts E’s offer, his or her final consumption level of three units of each commodity would be unchanged. These are, of course, very ‘hard bargains’ and we might expect in general A and B to benefit from their acquaintance with E. For the moment, however, we will assume simply that E offers to purchase y at a price of \x (that is, sell x at price of 4y), and sell y at a price of |x (that is, purchase x at a price of 3y) and we have seen that this would leave A and

B no better or worse off than before. Person C on the other hand, will benefit noticeably from trade with E assuming he or she faces the same price ratio as B. By specialising in x (three units), C can trade 0.75 units of x for 2.25 units of y. Similarly, person D can specialise in x (three units) and through trade achieve the same position as C. The argument is precisely the same as was presented in Chapter 1 and the entries on the right-hand side of Table 3.1 are a combination of the first two lines of Table 1.5.

The important difference is that, whereas we assumed in each line of Table 1.5 that every contractor faced the same price ratio set by an auctioneer, in Table 3.1 we have assumed that contractors B, C and D faced a different price ratio from contractor A, and that these price ratios were negotiated with an entrepreneur. The entrepreneur in this simple situation acts merely as an intermediary. By spotting that currently unexploited gains from trade existed, the entrepreneur was able to use that knowledge both to realise the gains and to appropriate a proportion of them for him or herself. Each person’s individual benefit (in terms of units of x and y) from the reallocation of resources initiated by the entrepreneur is recorded in parenthesis in the last column of Table 3.1. Person D appears to have gained most of all, but this, of course, is the result of our simple assumption that E offered the same terms of trade to all sellers of x. If the entrepreneur could have kept B, C and D apart and negotiated individually with them, then a sufficiently ‘hardnosed’ approach might have diverted a larger proportion of the gains from trade in E’s direction. However, in the particular arithmetical example presented, the entrepreneur gains 0.5 units of x and 0.5 of y. Of the units of y supplied by person A, 7.5 units are in total given to B, C and D; while of the 2.5 units of x supplied altogether by B, C and D, only two units are given to A.

Person E achieves a consumption level of 0.5x and 0.5y. This represents ‘pure entrepreneurial profit’. It has nothing to do with interest payments on capital employed. Indeed, it has nothing to do with a return to any ‘factor’ as conventionally defined. It arises out of entrepreneurial activity and the possession of a particular kind of knowledge: the knowledge that opportunities exist which no one has spotted before. The entrepreneur acts as a coordinator of resources, and his or her profit is taken from the gains in efficiency which accompany his/her activity. Note that the gains to persons C and D recorded in Table 3.1 are not entrepreneurial profits even though they also are part of the efficiency gain resulting from the reallocation of resources. Persons C and D did not spot the potential benefits available from change; they merely responded to the entrepreneur’s offer. Their gain is therefore a type of ‘windfall’; a portion of the increased output which eluded the grasp of the entrepreneur.

An important problem was studiously ignored in the paragraphs above, however. Clearly the entrepreneur does not negotiate simultaneously with all the people playing a part in his or her plans. Had s/he done so, s/he would be unable to offer person A different terms of trade from the others, and the mechanism which enables some profit to be realised would be ineffective. In effect, the entrepreneur’s knowledge would be instantly available to the others and no entrepreneurial profit could therefore be derived from it. As Richardson (1960, p.57) puts it: ‘a general profit opportunity, which is both known to everyone and equally capable of being exploited by everyone, is, in an important sense, a profit opportunity for no one in particular’. On the other hand, if the entrepreneur, who it will be recalled has no resources of his or her own, is to trade with A first, where is s/he to find the units of x required to make an offer? One solution to this problem might involve E persuading person A to supply the eight units of y in advance of E’s delivery of the x. In this case, person A would be acting as a capitalist supplying the entrepreneur with the resources required to test his or her hunch in the market. We would then expect that person A would require compensation both for the delay and for the perceived uncertainty associated with the ultimate delivery of x. Person A would have to take the risk that E’s confidence in her ability to deliver a given quantity of x bya certain date is misplaced and that the entrepreneurial plan might fail. For Knight, as we have seen, this bearing of uncertainty would make person A an entrepreneur, but for Kirzner this is not necessarily the case. E is the person who thinks s/he has spotted new opportunities, and it is E who stands to gain pure entrepreneurial profits if this judgement proves correct. Kirzner (1979) is quite specific on this point: ‘Entrepreneurial profits …are not captured by owners, in their capacity as owners, at all. They are captured, instead, by men who exercise pure entrepreneurship, for which ownership is never a condition’ (p. 94). Where time must elapse between purchase and sale: ‘It is still correct to insist that the entrepreneur requires no investment of any kind. If the surplus …is sufficient to enable the entrepreneur to offer an interest payment attractive enough to persuade someone to advance the necessary funds… the entrepreneur has discovered a way of obtaining pure profit, without the need to invest anything at all’ (Kirzner, 1973, p. 49).11

Of course, nothing guarantees that the penniless entrepreneur will succeed in persuading capitalists to advance their funds, but, as was emphasised in Chapter 2: ‘These costs of securing recognition of one’s competence and trustworthiness are truly social costs. They would exist under any system of economic organisation’ (Kirzner, 1979, p. 101). All that can be said is that an entrepreneur who is also a resource owner will find it easier to back his or her hunches and benefit from his or her knowledge since these transactions costs can be avoided.12 The entrepreneur lends to him or herself.13

3.2. Entrepreneurship and knowledge

For Kirzner, the entrepreneur is the person who perceives the opportunities and hence benefits from the possession of knowledge not apparently possessed by others. Thus entrepreneurship is central to the process by which information is disseminated throughout the economy. This emphasis on process is distinctive of the modern ‘Austrian’ school of thought, and it was noted in Chapter 1 that the major Austrian criticism of neoclassical equilibrium theory is the implicit assumption of perfect knowledge which underlies it.

It would, however, be totally misleading simply to leave the impression that neoclassical theory has nothing of substance to say about the problem of information. Our discussion of the information requirements underlying general equilibrium theory still stands, but neoclassical economists have developed tools which enable them to handle some problems in the economics of information very effectively. Since the early 1960s, the assumption of ‘costless knowledge’ has been dropped and replaced by the idea that knowledge is a valuable good which it is costly to acquire. This opens the way to the study of the behaviour of rational, maximising, calculating agents in the field of acquiring knowledge. A good example of such an approach is the analysis of ‘search behaviour’, a literature which emanates from Stigler’s (1961) paper on the economics of information. Essentially the idea is simply that resources will be invested in search (that is, acquiring information) up to the point at which the marginal expected benefits of the information thus obtained equal the marginal costs of obtaining it.

It is worth taking a brief look at the elements of this literature in order to draw out the contrast between the approach of the Austrians and that of ‘standard’ theory to the problem of information. Take the very simplest case discussed by Stigler (1961). Suppose that a person wishes to purchase a certain commodity. In the textbook world of perfect competition, the price of this commodity is known with certainty by every transactor. But in reality, of course, the price quoted by some sellers will be higher than others, and consumers will usually benefit by ‘shopping around’. Imagine now that the consumer knows something about the probability of being quoted a price within certain ranges upon any given enquiry. Indeed, suppose that s/he knows that the distribution of quoted prices is rectangular and that the price quoted may vary between £0 and £1. Such a person might argue that if s/he simply plans to buy from the first person s/he contacts s/he will expect to pay a price of £0.5, but, of course, there is a 0.5 probability that s/he will pay a price greater than £0.5. If s/he obtains two price quotes and then accepts the minimum of these two prices, the person will reduce the expected price that s/he pays. The probability of paying more than £0.5 for the item (that is, that both quotes turn out to be greater than £0.5) will be reduced to 0.25, while the probability that at least one of the two quotes is less than £0.5 would be 0.75. Clearly, ‘shopping around’ favourably affects the probability distribution of the minimum price encountered. It can be shown in this case14 that if n is the number of price quotes obtained, the mathematical expectation of the price paid will be 1/(n + 1).

If we now assume that the person intends to buy a quantity q of the commodity (which for simplicity we take as independent of the minimum price quoted) and that the extra cost of getting one more price quote is a constant c, it is a routine minimisation problem to calculate the number of searches which will minimise the expected total cost (expenditure plus search costs) of buying q units of the commodity. The expected total cost E(T) of buying q units of the commodity will be

E(T) = [q/(n +1)] + nc.

The value of n that minimises this expression is given by

n* = (q/c) -1.

If, for example, the person is to purchase a single unit of the commodity (Stigler uses once more the example of a second-hand car!) and if c =1/9 then the first-order condition tells us that two price quotes will be optimal. Clearly the lower the cost of search c, the greater the optimal number of searches (if c = 1/100, n = 9). Not surprisingly, the more units of the commodity to be purchased, the greater the optimal search effort (with q =100 and c = 1/100, n = 99).

Stigler’s analysis therefore involves the searcher in calculating the best sample size of price offers to choose. Once the problem is solved, the searcher goes out into the market and contacts the requisite number of sellers. This predetermined-sample-size strategy, however, clearly has its disadvantages. If q = 1 and c = 1/9 and the buyer approaches the first of the two sellers s/he is going to sample and finds that s/he is offered a price of £0.1, it is not at all clear that the person should bother to contact anyone else. Rather than a predetermined sample-size strategy, therefore, it has been suggested that a sequential-search strategy would be more sensible. At each stage, the searcher asks whether, given the known frequency distribution of price offers and the lowest price so far encountered, a further unit of search would be worthwhile.

Assuming that q= 1 and the frequency distribution is rectangular, as above, it is a simple matter to show15 that further search at any stage will not be worthwhile (in terms of reducing expected costs) if

![]()

If the most recent price offer is less than V(2c) it is best to accept it and search no more. V(2c) is called a ‘reservation price’. The sequential-search strategy therefore comes down to the calculation of the optimal reservation price. Search then continues until a price below this level is quoted.16

This brief excursion into neoclassical search theory is sufficient at least to uncover the essential rationale of the approach. Neoclassical theory is evidently quite capable of analysing some types of search, but, if this is so, what is it that distinguishes Kirzner’s ‘alert’ entrepreneur who discovers new information from Stigler’s searcher after new information, and is the distinction of any importance?

The idea of a rational investment programme in the acquisition of new knowledge, as suggested by neoclassical search theory, is in some respects rather odd, for it implies that it is possible to estimate the value of new knowledge in advance of its discovery. Presumably, though, this will only be possible if, in some sense, we already know what we are looking for along with the probability of finding it. It is rather as if we are searching for something of which we once had full knowledge but have inadvertently mislaid. Stigler’s searcher decides how much time it is worth spending rummaging through dusty attics and untidy drawers looking for a sketch which (the family recalls) Aunt Enid thought might be by Lautrec. Kirzner’s entrepreneur enters a house and glances lazily at the pictures which have been hanging in the same place for years. ‘Isn’t that a Lautrec on the wall?’17

For Kirzner, entrepreneurial knowledge is not the sort of knowledge which is the yield to a rational investment policy in search. Entrepreneurial knowledge does not involve resource inputs but is ‘costless’. It arises when someone notices an opportunity which may have been available all along – something which was staring everyone in the face but had somehow escaped their attention (Kirzner, 1979, pp.129-31).18 ‘Why didn’t I think of that?’ is the exasperated cry of most of us when confronted with some simple and effective piece of enterprise. Part of our exasperation derives from the appreciation that we may have possessed all the individual pieces of information required to perceive the same opportunity. The significance of the information somehow unfortunately escaped us, and we failed to ‘put it together’ to form a coherent and profitable picture. Such self-admonishment is quite out of place in the world of neoclassical search. For in that world there are no mistakes and regrets whether deriving from omission or commission. True, a decision having been made, a person may later acquire knowledge which reveals how much better some alternative decision might have been, but, providing that within the context of the knowledge available at the time the decision was correct and providing that investment in information had been carried to the optimal point, no real ‘error’ can be said to have occurred. The neoclassical world must always ultimately be a world of calculation in which ‘observation’ is taken for granted.

4. Schumpeter

4.1. Entrepreneurship and equilibrium

As we have seen, Kirzner’s approach to the entrepreneur is that s/he is alert to hitherto unexploited gains from trade. At any one time, economic life consists of a complex pattern of exchange relationships. The entrepreneur acts as the catalyst which loosens some transactional bonds and forges new ones. In our simple example above, the entrepreneur was the motive force impelling society towards some ultimate ‘solution’ represented by the figures in Tables 1.4 and 1.5. Once this position is achieved, no further possible entrepreneurial profits are available. By definition, if the allocation of resources is a ‘core’ allocation, no reallocation can benefit any group of people, and hence all the ‘alertness’ in the world will be of no avail in the spotting of further efficiency gains. Thus, for Kirzner, entrepreneurship is associated with disequilibrium, and concerns the process by which the economy moves towards equilibrium.

The very notion of the entrepreneur as a trader and middleman suggests the gradual and incremental approach to equilibrium, as differences in relative prices are spotted and arbitrage takes place. As Loasby (1982) emphasises, there is a similarity here with Marshall’s19 approach to economic change, with its emphasis on numberless small modifications of established procedures tested out in the marketplace by ‘the alert businessman’. It is the tradition of Mises and of Hayek, who both emphasise the small-scale and ‘local’ character of much entrepreneurship and the dependence of this entrepreneurship on ‘knowledge of time and place’ or ‘tacit knowledge’20 which ‘by its nature cannot enter into statistics’ (Hayek, 1945, p.21).

There is, however, a more heroic conception of the entrepreneur than this. It is easy to see how Kirzner’s approach might lead to the conclusion that virtually everyone acts entrepreneurially, at least to some degree. For Schumpeter (1943), on the other hand, the entrepreneur is an extraordinary person who brings about extraordinary events. In Schumpeter’s view, the entrepreneur is a revolutionary, an innovator overturning tried and tested convention and producing novelty. Such boldness and confidence ‘requires aptitudes that are present only in a small fraction of the population’ (p. 132) and represents a ‘distinct economic function’. This function of the entrepreneur ‘is to reform or revolutionise the pattern of production by exploiting an invention or, more generally, an untried technological possibility for producing a new commodity or producing an old one in a new way, by opening up a new source of supply of materials or a new outlet for products, by reorganising an industry and so on’ (p. 132).

In order not to give a misleading impression, it should be added that Schumpeter is careful to say that railroad construction or the generation of electrical power were ‘spectacular instances’ and that his conception of entrepreneurship would include introducing a new kind of ‘sausage or toothbrush’. The crucial characteristic is not scale as such but novelty in a technological sense. New products, new processes or new types of organisation are thrust upon the world, often in the face of violent opposition. The military analogy with generalship or the ‘medieval warlords, great or small’ (p. 133) is considered by Schumpeter most appropriate because of the importance of ‘individual leadership acting by virtue of personal force and personal responsibility for success’.

Because of this emphasis on the energy of individual entrepreneurs and the introduction of new products and processes, Schumpeter sees entrepreneurship as a disruptive, destabilising force, responsible for cycles of prosperity and depression. He refers explicitly to the disequilibrating impact of the new products or methods’ (p. 132, emphasis added). This is clearly a rather different conception from that of Kirzner. Kirzner’s entrepreneur is engaged in spotting ways of making the best of a given set of technical circumstances. Technology, the state of the arts, of skills and scientific knowledge, are a backdrop to, rather than the outcome of, entrepreneurial activities. The possibilities for the full use of available resources in given technical circumstances still have to be uncovered, but this is all the entrepreneur is seen as doing. The production-possibility curves applying to each of the four contractors in our arithmetical example were drawn on the assumption that they represented the outer bound of all the possible points attainable in the prevailing state of technological knowledge available to each individual. These curves would alter with changes in scientific and technical information. Thus, it is usual to contrast Kirzner’s approach with Schumpeter’s by arguing that Kirzner’s entrepreneur will get us to point A in Figure 1.1, a point on the community-production-possibility frontier representing a given state of technical knowledge; while Schumpeter’s entrepreneur is engaged in shifting the production-possibility frontier by instituting innovations. It is in this sense that Kirzner’s entrepreneur gets us to an equilibrium point A, while Schumpeter’s entrepreneur disturbs this position of equilibrium by redefining the technical constraints.

This distinction between two types of entrepreneur, one an equilibrating and the other a disequilibrating force, is not, however, as clear-cut as at first sight it might appear. It would seem inconsistent with Kirzner’s basic philosophy to assume that people are aware of all the purely technical possibilities available to them, and that their lack of knowledge concerns only the possibilities of benefiting through the process of exchange. Rather, consistency requires us to argue that each person will have limited technical knowledge; that over time, whether by accident or design, they will acquire additional technical knowledge; and that entrepreneurial perception will be as significant in appreciating the consequences of newly acquired technical knowledge as knowledge of price differentials or any other objective pieces of information. It is difficult to see why the person who, upon becoming acquainted with the properties of some artificial fibre, realises that, using this fibre, toothbrushes might be made more cheaply than with natural fibre, is acting as a Schumpeterian rather than Kirznerian entrepreneur. If, ultimately, it is the perception of opportunities which defines the entrepreneur, then Kirzner’s framework must surely embrace the marketing of new sausages and toothbrushes.

To maintain the distinction between equilibrating and disequilibrating entrepreneurs therefore seems to require that we distinguish between the use of ‘new’ technical knowledge, and the new use of technical knowledge which has been known for some time – at least, known to some people. Thus, the person who first manufactures and uses an artificial fibre is Schumpeterian, whereas the people who gradually come to perceive the multifarious possible applications are Kirznerian. This distinction would certainly seem consistent with the ‘flavour’ of the two writers, but whether it is tenable is a question which, for the present, we will simply ignore.

4.2. The fate of the entrepreneur

Given the differences in emphasis between Schumpeter and Kirzner it is somewhat surprising to find one strand of thought common to both.

Entrepreneurial activity serves to render obsolete the entrepreneur. This is perhaps easier to understand in the case of Kirzner since we have already drawn attention to the fact that, as advantage is taken of the available opportunities, the approach of equilibrium reduces the scope for further entrepreneurial insights. Kirzner, it should be emphasised, does not explicitly predict the demise of the entrepreneur, as does Schumpeter. Exogenous changes in tastes and technology can be relied upon to create continuous opportunities for entrepreneurship, but it does appear to be a characteristic of Kirzner’s system that it would run down in the absence of these outside forces.

In the case of Schumpeter, the idea of the entrepreneur as a destabiliser might suggest the conclusion that the commercial exploitation of new inventions could go on indefinitely and with it the distinctive role of the entrepreneur. Schumpeter, however, took a quite different view. The progress of capitalism, he asserted, would eventually reduce the importance of the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur was required initially to overcome resistance to change but now ‘innovation itself is being reduced to routine. Technological progress is increasingly becoming the business of teams of trained specialists who turn out what is required and make it work in predictable ways’ (p. 132). ‘Economic progress tends to become depersonalised and automatised’ (p. 133). The giant industrial unit ‘ousts the entrepreneur’ and the specialist instigators of progress eventually receive ‘wages such as are paid for current administrative work’ (p. 134).

This conception is, of course, quite alien to Kirzner since ‘alertness’ to new opportunities could hardly be ‘depersonalised’ as envisaged by Schumpeter. Clearly ‘perception’ as such is not considered by Schumpeter to give rise to any special problems. Progress derives from technological change, and this can apparently develop a momentum of its own. The entrepreneur is required to galvanise the economic system into motion after which, like some material object in Newtonian physics, all resisting forces having been removed, it continues indefinitely along its predicted path.21

Schumpeter’s prediction of the obsolescence of the entrepreneur is one of the most celebrated aspects of his work. It has naturally attracted considerable critical attention which cannot be considered here in detail. However, the different interpretations that can be placed on similar observations are startling in the study of economics. Whereas large corporate entities in Schumpeter’s view ‘oust the entrepreneur’, Kirzner sees them as magnets attracting entrepreneurial talent. The corporation is ‘an ingenious, unplanned device that eases the access of entrepreneurial talent to sources of large-scale financing’ (1979, p. 105). It reduces the transactions costs, considered earlier, involved in gaining access to capitalists’ funds.22 Schumpeter observes the large corporation and finds in it an environment unconducive to the survival of the entrepreneur. Kirzner observes the same phenomenon and pronounces it a structure which has evolved to permit a more effective use of entrepreneurial alertness. Further, Schumpeter’s view that, within the corporation, technical progress becomes automatic was greeted even at the time with scepticism if not disbelief in some quarters. One such critic (Jewkes, 1948), with barely concealed contempt for a view which so contradicted his experience of aircraft production and research during the Second World War in the UK, wrote that: ‘Left to themselves, and having no particular reasons for taking risks, teams of technicians will almost invariably bog themselves down without direction or purpose . . . Take away the motive force of innovation – the business man – and the cautious and conservative habits of the consumer and technician would roll back over us with deadening effect’ (p. 21).

5. Shackle

Shackle is celebrated not so much for his specific views on the entrepreneur as for his writing on the nature of choice in general. A brief consideration of his work is relevant here, however, because it impinges directly on the issues under discussion. We have seen how, in Kirzner’s conception of things, the entrepreneur perceives opportunities. Shackle would insist that the entrepreneur must imagine these opportunities. This is not to use the word ‘imagine’ in the popular sense, to imply that the opportunities are illusions, but rather simply to assert that any choice involves the exercise of imagining a possible future state of affairs. We do not choose between ‘facts’ or ‘certainties’. When we act, it is on the basis of the imagined consequences. Even in the simplest possible case of choosing between a loaf of bread and a pint of beer we must choose on the basis of how we imagine our feelings will be when we actually get round to eating the bread or drinking the beer. This is so even if this occurrence follows the act of choice by a mere fraction of a second. Once we have drunk the beer we know what it was like, but this information is not relevant to any act of choice. When we approach the bar for our second pint we will of course, remember the experience of drinking the first, but it is strictly not this recollection of past drinks which determines our choice, but the consequent expectation of the future drink. Thus, Shackle is the complete subjectivist. All neoclassical economists are subjectivists in the sense that they accept that my valuation of beer in terms of the amount of something else I am prepared to sacrifice to get another pint is simply an expression of my own subjective preferences. Shackle, however, goes further to argue that the so-called ‘objects of choice’ (the bread and the beer) are not objects at all, but subjective impressions about the future: ‘If my theme be accepted, there is nothing among which the individual can make a choice, except the creations of his own thought’ (1979b, p. 26).

Such radical subjectivism has immediate implications for his view of the entrepreneur. Shackle, like Kirzner, is often placed within the group of writers called ‘Austrian’, yet the implications of his philosophy are so subversive that by comparison the main Austrian camp appears a haven of conservatism. Kirzner’s entrepreneur gradually uncovers the opportunities presented by objectively given constraints. In the process, s/he takes us to an equilibrium in which all opportunities are finally exploited. If, though, opportunities do not have an objective existence independent of their discoverer, but spring rather from each person’s imagination, they cannot be recorded, even conceptually, in a finite list unless the human imagination itself is capable of exhaustion. Thus, for Shackle there can be no state of ‘full coordination’; no equilibrium representing the final resting place of the economy. Underlying Kirzner, there is a form of historical determinism, a final destination. Underlying Shackle, there is simply ‘the anarchy of history’ (1979b, p.31). His view is clearly anti-determinist, and rejects the whole concept of equilibrium.23

To refer once more to our arithmetical illustration of the four individuals, Kirzner’s entrepreneur spots the possibilities presented by four different, but objectively existing, production-possibility curves, but these constraints and the opportunities delimited by them are, for Shackle, simply what people at any given time think they are, and can never have the status of ultimate objective unchanging facts. Tomorrow, person A may imagine new ways of using his or her resources for different or for similar purposes. Either way, the established pattern is upset and new opportunities for entrepreneurship are created. As Loasby (1982b) puts it: ‘Kirzner’s entrepreneurs are alert, Shackle’s are creative’ (p. 119). Shackle rejects conceptions of the economic process which ‘rule a line under the sum of human knowledge, the total human inventive accomplishment’ (Shackle, 1982, p. 225).

If comparisons are to be made, Shackle’s entrepreneur has perhaps a greater affinity with that of Schumpeter than with that of Kirzner. The emphasis on innovation on the one hand (Schumpeter) and the creative imagination on the other (Shackle) are closely related.24 Further, the ideas that entrepreneurial activity disrupts equilibrium on the one hand (Schumpeter) and denies the possibility of equilibrium on the other (Shackle), while clearly not formally compatible, nevertheless suggest a similar conception of its impact. In other ways, however, Schumpeter and Shackle are far apart. Neither Schumpeter’s view that only a small proportion of people have the qualities to be entrepreneurs, nor his view that the entrepreneurial function is doomed to extinction, seem compatible with

Shackle’s philosophy, for Shackle’s view is ultimately grounded on his response to the most fundamental question of what it really means ‘to choose’. Everyone faces the necessity of choice, and in choosing they exercise the entrepreneurial faculty of imagination. Thus, so long as there are human beings and choices to be made, so too will there be entrepreneurs. Shackle’s approach to the entrepreneur, therefore, is not part of a theory of business enterprise as commonly understood, nor is it like Kirzner’s framework an attempt to consider the process by which equilibrium is attained; rather it is an integral part of his whole approach to the theory of individual choice.

6. Casson

To be told that entrepreneurship is an inevitable concomitant of the human condition, while important conceptually and philosophically, is light years away from the popular conception of the entrepreneur with which we started. In principle we may accept the case that all decisions are speculative, but we may also accept that some decisions are more speculative than others, and that some people are better at making these more speculative decisions than others. If the entrepreneur is ultimately to play a part within a theory of the firm, there seems no escaping the idea that the entrepreneur possesses skills which are special, if not in kind then in degree. Thus, Knight’s entrepreneur is unusually willing to tolerate uncertainty, Kirzner’s is especially alert, Schumpeter’s is ruthlessly capable of smashing the opposition, and Shackle’s is endowed with a particularly creative imagination.

Casson (1982) attempts to synthesise and extend these conceptions of the entrepreneur. His definition is as follows: ‘An entrepreneur is someone who specialises in taking judgemental decisions about the coordination of scarce resources’ (p. 23). Central to this definition is the notion of a judgemental decision. This, Casson defines as a decision ‘where different individuals, sharing the same objectives and acting under similar circumstances, would make different decisions’ (p.24). They would make different decisions because they have ‘different access to information, or different interpretation of it’. It follows from this definition that an entrepreneur will be a person whose judgement inevitably differs from the judgement of others. The reward, then, for an entrepreneur derives from backing his or her judgement and being proved right by subsequent events.

A single chapter does not allow the space carefully to develop every point of comparison between Casson’s view of the entrepreneur and those which we have already encountered. Nevertheless a few observations may help to make clear the distinctive contribution of Casson and at the same time clarify some of the issues discussed in earlier sections.

Casson has one fundamental point of agreement with the ‘Austrian’ theorists. The entrepreneur’s reward is a residual income not a contractual income, and it is derived from the process of exchange or ‘market-making activities’. For Casson, the middleman is an entrepreneur, just as for Kirzner. Entrepreneurs reallocate resources. To achieve such a resource reallocation they must trade in property rights (see Chapter 4) and if their attempts at coordination (that is, resource reallocation) are successful they will derive a pure entrepreneurial profit. The person who judges that a firm could be reorganised profitably, purchases the firm, changes its operations (by recontracting with the inputs) and sells it for a gain is clearly an entrepreneur. The person who thinks that a group of people, at present working independently, would be more effective as a team, and who forms the team by employing each at a wage equivalent to their existing income, thereby appropriates the productivity gains achievable through team effort. Such a person is also clearly an entrepreneur.25

Even at this level there are, of course, differences of emphasis. Thus, as we have seen, Casson insists that these ‘market makers’ or ‘coordinators’ are specialists, whereas Kirzner sees any alert person as a potential entrepreneur. Further, Casson emphasises that entrepreneurs require command over resources if they are to back their judgements and that this is likely to imply personal wealth. He refers to people with entrepreneurial ability but no access to capital as ‘unqualified’ (p. 333). Kirzner would accept that lack of personal capital presents extra transactional difficulties (see above section 2.3.1) but would almost certainly argue that anyone with entrepreneurial talent could never be in an objective sense totally ‘unqualified’. Entrepreneurial talent will find ways of securing control of resources, and ‘alertness’ to possible new ways of doing so is as much a part of entrepreneurial talent as alertness to possible new uses for the resources themselves.

In other respects, Casson and the Austrian theorists are far apart. For Schumpeter, Kirzner and Shackle, the ‘pace of change’ is determined by the activities of the entrepreneurs. Each had different ideas of the personal qualities which were important in instigating change, and they differed on the question of whether change thus instigated was disequilibrating or equilibrating, but each was clear that change and entrepreneurship go together like a horse and cart and that the entrepreneur is the horse. In Casson’s scheme, however, there is a tendency to view ‘the pace of change’ as an accompaniment to entrepreneurial activity rather than as its result. This makes Casson’s entrepreneur more akin to that of Knight – the person who, in an uncertain (changing) world, specialises in making difficult judgements and receives a profit for bearing uninsurable risk (Casson would say for exhibiting superior judgement). Indeed, Casson himself writes that his work on the entrepreneur is in many parts ‘simply a reformulation of ideas first presented by Knight’ (p. 373).

Casson’s entrepreneur perhaps requires Kirznerian perception to spot the information most pertinent to the judgemental decision at hand, and requires Shackle’s imaginative faculty to ponder future possibilities, but these features are not greatly emphasised. The reason is straightforward and fundamental. Casson wants to discuss more than the rationale of the entrepreneur. He realises the importance of the entrepreneur to the process of resource coordination and wishes to consider further questions upon which an economic theory might cast some light. Ultimately, Casson wishes to construct a predictive theory of entrepreneurship. Shackle’s sublime epistemology is all very well but there are some important down-to-earth issues which it does not really help us to address. Why are some economic systems apparently more successful at resource reallocation than others? How are entrepreneurs ‘allocated’ to the task of making judgemental decisions? What institutional arrangements facilitate the exercise of entrepreneurship? What factors determine the ‘supply’ of entrepreneurial talent? The language in these questions, which clearly implies the notion of entrepreneurship as a ‘resource’ similar to other factors of production to be ‘allocated’, is clearly alien to the Austrian conception. Yet, as Casson recognises early on (p. 9), ‘the Austrian school… is committed to extreme subjectivism – a philosophical standpoint which makes a predictive theory of the entrepreneur impossible’. He accepts that no predictive theory of the behaviour of an individual entrepreneur is possible, but this does not rule out, he argues, a theory of the aggregate behaviour of a population of entrepreneurs. Fortified with this thought, Casson braces the hostility of the entire Austrian camp and proceeds to consider entrepreneurship within a supply and demand framework.

Figure 3.1 reproduces Casson’s diagrammatic apparatus. The curves, though labelled DD’ and SS’ should not be regarded as supply and demand curves as conventionally interpreted. Consider the DD’ curve first. Along this curve is plotted the expected reward per entrepreneur as the number of active entrepreneurs increases. It is drawn assuming a given pace of change in the economy. Thus, new opportunities are cropping up at a certain pace and it is the task of the entrepreneurs to spot them and take advantage of them. Notice how similar to Kirzner’s is this conception. Whereas Kirzner sees the entrepreneur as gradually coming to perceive the opportunities latent in given circumstances, Casson sees the entrepreneur as spotting a certain proportion of the opportunities thrown up as circumstances change. It is as if Schumpeter’s entrepreneurial horse has done its work and the cart is proceeding under its own momentum directed not by teams of experts, as Schumpeter expected, but by specialist Kirznerian entrepreneurs placed in this slightly different environment by Casson.

As the number of active entrepreneurs increases, the expected return to each declines. This is to imply the usual competitive postulate in a slightly unfamiliar guise. The more active entrepreneurs there are, the more likely it is that any given opportunity will have already been spotted by someone else, and the length of time elapsing before a newly spotted opportunity is emulated by others is reduced. Thus the curve DD’ slopes downwards to the right and its position is dependent upon the pace of change. Curve SS’, on the other hand, is the supply curve of ‘qualified’ entrepreneurs (those with access to resources). It has a lower bound at the prevailing real wage on the reasonable grounds that no one will be an entrepreneur if the expected reward is below the wage rate. (This would, of course, not necessarily follow if entrepreneurs could be found who were risk lovers.) As the expected return to entrepreneurship rises above the wage rate, ‘qualified’ people desert employment to become specialist entrepreneurs. Further rises in the expected return induce yet others to become entrepreneurs who had before preferred leisure.

The position of the curve SS’ depends on the stock of entrepreneurial talent existing in the population (that is, the number of people who have the necessary judgemental qualities) and the proportion of these who are ‘qualified’ in Casson’s sense of having command over resources. People can become ‘qualified’ in three possible ways. They can have wealth of their own with which to pursue entrepreneurial ideas, they can have social contacts with wealthy individuals who know their character and appreciate their entrepreneurial potential, and they can gain command of resources from venture capitalists who do not know them but are specialists in screening for entrepreneurial flair, or from holding a senior position in a corporation.26 Thus, SS’ will shift with changes in the distribution of wealth, changes in social mobility, and changes in institutional mechanisms for screening for entrepreneurial ability.

Intersection of the two curves DD’ and SS’ gives an ‘equilibrium’ solution and determines the number of active entrepreneurs (N) and their expected rewards (V). These long-run ‘equilibrium’ expected rewards to entrepreneurship Casson interprets as a form of wage. In the short run, the return to each entrepreneur is a return to superior (monopoly) knowledge. In the long run, the expected return is ‘simply compensation for time and effort, namely for the time and effort spent in identifying and making judgemental decisions’ (p. 337). This long-run conception is not unlike that of J.B. Say which we encountered early on in this chapter. The number of active entrepreneurs (N), given the pace of change, will determine the proportion of new job opportunities that are exploited.

If this equilibrium or steady state is to be achieved, it is necessary that potential entrepreneurs should know the total number of entrepreneurs operating at any given time, along with the underlying pace of change of the economy. This information will be required if the expected return to entrepreneurship is to be assessed at each point and a decision made about the desirability of entry. It is worth noting that this mechanism will not necessarily lead smoothly to the equilibrium point. Suppose, for example, there were Nj active entrepreneurs, all those entrepreneurs in the interval NjN2 would be attracted to enter. Casson supposes that the numbers gradually rise and the expected reward gradually falls until equilibrium is achieved, but since we have not assumed that each entrepreneur knows the opportunity costs faced by other entrepreneurs, all we can really tell is that all entrepreneurs in the interval N1N2 will enter. Such a mass entry, however, will greatly depress the expected reward per entrepreneur (V2). In this way, a cycle could be generated not unlike the ‘cobweb cycle’ of principles of economics textbooks. It is also similar in conception to Schumpeter’s view of cycles of entrepreneurial activity. Clearly the decision whether or not to become an entrepreneur is as ‘judgemental’ as the individual decisions the entrepreneur makes after he or she has entered. It would be ironical indeed to have to conclude that markets in general are coordinated by entrepreneurial activity, but that the market for entrepreneurs requires an auctioneer.

Casson’s presentation of the market for entrepreneurs has many of the strengths which are associated with neoclassical ways of thinking. Drawing supply and demand curves can be a powerful aid to thought, which is presumably why they were invented and have proved so popular. Such diagrams immediately require us to specify what determines the shapes and positions of the curves, and in so doing we isolate what we think are the important influences on the market. Whether the concept of a steady-state equilibrium in the market for entrepreneurs is a theoretical advance, however, will have to be judged by future research effort. In principle the framework should permit comparative static properties to be deduced which are testable statistically. In practice it is not clear that some of the crucial variables in the model are amenable to statistical measurement; for example, the social and institutional factors behind the supply curve. Further, economists of the Austrian school would argue that the attempt to introduce the equilibrium method into studies of entrepreneurship is fundamentally misconceived. For the DD’ curve to mean anything it has to be assumed that all entrepreneurs know ‘the pace of economic change’ and can calculate the expected rewards from their entrepreneurial efforts. There seems to be no very clear explanation as to why such a construction is likely to exhibit much stability. In the context of a firm’s market demand curve, Shackle (1982, p. 230) defends the geometrical figure as an aid to thought, but dismisses the possibility of knowing much about it in practice: ‘It is a mere thread floating wildly in the gale.’ There seems little possibility that he would take a different view of the demand for entrepreneurs.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

Hello there, You’ve done a fantastic job. I’ll definitely digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am sure they’ll be benefited from this website.

I’d constantly want to be update on new blog posts on this site, saved to bookmarks! .