Information is costly to obtain. Finding out about the opportunities which are potentially available, about the quality of the goods and services on offer, and about the appropriate responses to various possible future contingencies, involves time and effort. The absence of information, as we have seen, can inhibit the process of exchange, but if the costs of acquiring the relevant information are too great the failure of exchange to occur is both predictable and efficient. This was the essential bone of contention in the celebrated exchange between Arrow (1962) and Demsetz (1969) already referred to in the section above. To observe the failure of exchange to take place is not to prove inefficiency if information costs exist. To assert otherwise is, according to Demsetz, to commit the fallacy of the ‘free lunch’ (that is, to assume that information is potentially available without cost). Alternatively, the fallacy involved might be described as the ‘people could be different’ fallacy (that is, that somehow or other people could be induced not to exploit asymmetries in information and that the problem of moral hazard might go away).

As we have taken some pains to elaborate, however, the process of exchange inevitably entails overcoming these transactional difficulties. To assume away the problem of information is not very helpful if the object of study is the theory of the firm, but it would be equally unhelpful to assume that no attempts are made to mitigate the problem. If exchange is potentially advantageous we would expect the would-be transactors to devise mechanisms which enable it to proceed. Institutions will develop which economise on information costs and permit trades which would otherwise be impossible to take place.

1. Money

The idea that institutions develop in response to transactions costs is familiar enough in certain areas. All students learn at an early stage the advantages associated with the use of money as a medium of exchange relative to a system of barter. Elementary textbooks will usually contain examples of the difficulties faced by a fisherman vainly searching for a cobbler who wants a piece of haddock, to use D.H. Robertson’s example. The problem of establishing a ‘double coincidence of wants’ is a slightly misleading way of looking at the issue of barter, however. A barter system – that is, a system involving the direct exchange of goods and services without the use of money – does not strictly require a ‘double coincidence of wants’ unless it is stipulated that all exchange transactions must be bilateral ones. A fisherman can obtain shoes from a cobbler under a system of barter even if the cobbler has no taste for fish, but to do so it will be necessary to involve other parties in a joint multilateral agreement. For example, a baker may agree to provide a certain quantity of bread to the cobbler. In exchange the fisherman provides the baker with fish and receives shoes from the cobbler. Finding the parties willing to take part in this ‘triangular trade’ and negotiating the terms of the contract, however, is clearly going to be more costly and require greater information than a simple bilateral deal. In principle, it is possible to envisage more and more individuals taking part in these multilateral negotiations, but, as discussed in Chapter 1, obtaining a simultaneous agreement between many contractors is likely to be extremely difficult.

Money enables contractors to escape from the requirement of forming agreements simultaneously. A complex pattern of exchange relationships can instead be entered into through a sequence of bilateral arrangements. To return to our simple example, the shoemaker might accept fish in exchange for his shoes even when he dislikes fish if he knows of a baker who will be happy to exchange bread for fish. In this case, the fish is being used in the form of a medium of exchange since its value to the shoemaker depends entirely on its ability to procure him something else. Clearly, if the agreements described here are not entered into simultaneously the cobbler will want to be confident of the willingness of the baker to accept fish, and it is apparent that this is not necessarily or usually going to be the case. A medium of exchange will be more acceptable to the shoemaker the more widely acceptable it is known to be to other people. Where confidence in the wide acceptability of a medium of exchange is strong, it will not be necessary for the shoemaker to have knowledge of the demands of any particular baker. Any baker he knows will be happy to supply him with bread in exchange for money. This view of the origins of money is particularly associated with Carl Menger.4

As each economising individual becomes increasingly more aware of his economic interest, he is led by this interest, without any agreement, without legislative compulsion and even without regard to the public interest, to give his commodities in exchange for other, more saleable, commodities, even if he does not need them for any immediate consumption purpose.

This passage from Menger effectively describes the evolution of what Sugden (1986) calls a convention. As we saw in Chapter 1, conventions can develop gradually over time in response to the self-interested choices of contractors. People accept money because everyone else does, and a particular form of money may survive for long periods even if a different type, and hence a different convention, might have had better properties. Menger does hint, however, that ‘more saleable’ commodities are the ones that convention will tend to favour as money, and this raises the question of what is meant by that phrase. Alchian (1977a) provides a persuasive answer.

Imagine a world in which four commodities exist; Alchian supposes that these are called oil, wheat, diamonds and ‘C’. He notes that people cannot be expected to have expert knowledge of the characteristics of all the commodities in which they trade. Transactions costs, he assumes, will be highest when two ‘novices’ trade together, and will be lowest when the two traders are ‘experts’ in both commodities traded. We have already noted in our earlier discussion of asymmetric information that traders in certain products will have to establish a ‘reputation’ for trustworthiness if exchange is to take place. Let us suppose that by specialising in the trade of wheat in the sense that every exchange involves either its purchase or sale, a person becomes both an expert in assessing its quality and comes to command a high reputation. Such a reputation in a single commodity will be of little use, however, if the ‘expert’ wheat dealer is faced with the problem of assessing the qualities of oil or diamonds in the process of exchange. What is required if transactions costs are to be substantially reduced is a commodity in which everyone is an ‘expert’. Such a commodity will be one the qualities of which are very easy to assay. This is the primary characteristic of ‘money’ and is implicit in Menger’s use of the term ‘more saleable commodities’ as a description of money. Commodities are ‘more saleable’ if large numbers of people find their qualities can be assessed at very low cost. The use of money as an exchange medium reduces transactions costs because, in conjunction with the existence of specialist traders in other commodities, it increases the knowledge possessed by each contractor involved in an exchange. The specialist wheat trader will be an ‘expert’ in both wheat and money, while a customer (either a buyer or seller of wheat) will at least be an ‘expert’ in money. Of course, this in no way alters the fact that most of the specialist traders’ customers will be novices in wheat, and the implications of this have already been considered in the context of second-hand cars. In the absence of money, however, both parties to an exchange would usually be novices, while it is the use of money which permits the growth of specialised traders whose accumulated expertise and pursuit of goodwill are a response to the twin problems of asymmetric information and adverse selection.

Although a person accepting money in exchange for some good or service will feel confident that it can be used to procure other things, the precise terms of any future trades will not be known with certainty. Money is accepted in the expectation that it will permit the achievement of desired ends. It may even be the case that money is accepted with no specific and determinate ideas as to what is to be done with it. Instead, the person may prefer to wait upon events, and spend time searching for suitable opportunities. By reducing transactions costs, in other words, money permits wider search, and a more extensive and complex system of exchange transactions can occur than would otherwise be possible. Pigou (1949, p. 25) likened money to ‘a railway through the air, the loss of which would inflict on us the same sort of damage as we should suffer if the actual railways and roads, by which the different parts of the country are physically linked together were destroyed’. Money, that is, like the transport system, enables a wider range of transactions to take place.

But the existence of money implies more than a simple widening of possibilities. It implies that these possibilities are discovered by a process which continues over time. People hold money speculatively in the hope that to commit themselves later will be advantageous compared with deciding on a course of action immediately. The cobbler, for example, might have bartered his shoes immediately for fish. In fact, he preferred money because he expected to be able to use it later in ways yielding him greater satisfaction. The fact that in many everyday cases the time period involved might be quite short, and the cobbler may have intentions concerning the use of his money which are usually and routinely realised (he is very sure of the terms on which he can buy bread at the bakers) in no way changes the general principle.

Ignorance inevitably restricts exchange. Institutions which help to overcome the problems posed by ignorance are therefore expected to take root. To quote Loasby (1976): ‘Money, like the firm, is a means of handling the consequences of the excessive cost or the sheer impossibility of abolishing ignorance … both imply a negation of the concept of general equilibrium in favour of the continuing management of emerging events’ (p. 165).

2. Political Institutions

The idea that a fundamental political institution such as ‘the state’ might be interpreted as a means of overcoming impediments to the process of exchange has a long history. Consider for example a celebrated passage from Hume:

Two neighbours may agree to drain a meadow, which they possess in common: because it is easy for them to know each other’s mind; and each must perceive, that the immediate consequence of his failing in his part, is the abandoning of the whole project. But it is very difficult, and indeed impossible, that a thousand persons should agree in any such action; it being difficult for them to concert so complicated a design, and still more difficult for them to execute it; while each seeks a pretext to free himself of the trouble and expense, and would lay the whole burden on others. Political society easily remedies both these inconveniences . . .5

The focus of attention here is on the problem of ‘public goods’ (Samuelson, 1954; Musgrave, 1959). Some goods confer benefits not merely on a single consumer of the good but on a whole population of consumers simultaneously. Standard examples include defence, public health provisions, the services of lighthouses and so forth. Pure public goods are said to be ‘non-rival’ in consumption and ‘non-excludable’ (that is, it is technically not possible, or at least enormously costly, to prevent any individual person from enjoying the benefits of a public good provided by others). The result of these two characteristics is that ordinary market processes ‘fail’ in the sense that a multilateral agreement which might potentially benefit all the parties to it will not emerge spontaneously. In Chapter 1, the costs of simultaneous multilateral contracting have already been discussed in the context of private goods. There it was argued that although simultaneous agreement would be impossibly costly to achieve, alternatives existed which would be preferable to completely independent activity for the parties concerned. Resources would be allocated not in a single all-embracing moment of universal agreement but in a process involving bilateral exchanges and the use of money or the forming of institutions such as ‘firms’ to manage events as time advanced. Public goods, however, present us with a severe problem in that apparently the only alternative to a widespread multilateral agreement is no agreement. Resolution of this dilemma requires the existence of the ‘productive state’ and the institution of collective processes in place of market processes. Buchanan (1975, p.97) re-emphasises Hume’s point if in somewhat different style:

Only through governmental-collective processes can individuals secure the net benefits of goods and services that are characterised by extreme jointness efficiencies and by extreme non-excludability, goods and services which would tend to be provided suboptimally or not at all in the absence of collective- governmental action.

Public goods present obstacles to the formation of agreements of a particularly intractable nature, but they are not in principle different from those difficulties discussed in detail in section 2.2. There it was seen that the failure of transactors honestly to declare information could conceivably totally inhibit the development of certain insurance or other markets. Second-hand-car salesmen would always maintain that their wares were more reliable than they really were, and purchasers of insurance that the risks they faced were less than they really were. People, in other words, cannot be expected to declare honestly and voluntarily information which adversely influences the terms upon which they will trade when there are no cost-effective means of verifying the information. Trade in public goods is no exception. Further, where the simultaneous agreement of large numbers of individuals is involved, the problem of ‘bounded rationality’ cannot be overlooked. Thus, Hume’s two ‘inconveniences’ which, he argues, political society remedies, amount to the problems analysed earlier: ‘bounded rationality’ (‘it being difficult for them to concert so complicated a design’) and an extreme form of information asymmetry leading to opportunistic behaviour (‘each seeks a pretext to free himself of the trouble and expense’).

3. The Firm as a Nexus of Contracts

A provisional rationalisation of the emergence of ‘firms’ was suggested at the end of Chapter 1. From the standpoint of economic theory, the firm represented a ‘nexus of contracts’ so framed as to provide flexibility in the face of unpredictable events. Uncertainty, and the resulting difficulty of precisely specifying the terms of each person’s contract, thus constituted the starting point for the theory of the firm. This approach has its origins in a celebrated paper by Coase (1937), and the discussion of transactional difficulties above (section 2), now permits a further appraisal.

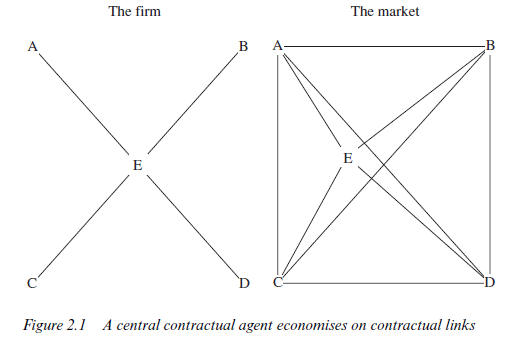

For Coase: ‘The main reason why it is profitable to establish a firm would seem to be that there is a cost of using the price mechanism’ (p. 336). Coase is here referring to such matters as ‘negotiating and concluding a separate contract for each exchange transaction’ (p.336). In the absence of a firm, each factor of production must contract with every other factor whose cooperation is required. Within the firm, each factor negotiates a single contract. In an extreme case where V individuals must all cooperate closely, a set of —1)/2 bilateral contracts would be required to bind the parties together. For five individuals, Figure 2.1 illustrates that ten agreements would be necessary. In a slightly different context, Williamson (1975, p.46) refers to this as the ‘all-channel network’. In the firm, on the other hand, one person would become the central contractual agent and a total of four contracts would be sufficient to link all the parties together.

It is important always to remember, however, that the advantages of the firm in terms of savings in contracting costs presuppose conditions of uncertainty. With costless knowledge there would be no advantages accruing to a reduced number of transactional bonds, since these bonds would be costless to establish. In Coase’s view of things the firm economises on transactions costs because bargaining over what has to be done, and on what precise terms, does not take place. The firm is characterised by the conscious organisation or direction of resources over time: ‘When the direction of resources (within the limits of the contract) becomes dependent on the buyer in this way, that relationship which I term a “firm” may be obtained’ (p. 337). Within the firm, people do what they are told to do.

More recent contributions to this literature have modified Coase’s conception in important respects. Below we look at several ‘contractual modes’ and discuss what distinguishes ‘market-like’ from ‘firm-like’ arrangements.

3.1.The deterministic contract

Under this scheme the contractors agree to perform specific services at certain future points in time. The obvious problem is that, in the extreme, it completely lacks flexibility and presupposes that the contracting parties are able to determine exactly what they will require at all relevant times in the future. It will be recalled that person A found it difficult to formulate a deterministic contract with his craftspeople because of the problem of predicting exactly what would be required of them at each stage.

This type of contracting is only likely to be observed, therefore, where the duration of an association is expected to be short, where conditions are stable and predictable so that routine procedures can be adopted, and where problems of information asymmetry are not serious.

3.2.The state-contingent contract

In a state-contingent contract, obligations are no longer deterministic and fixed. The requirements vary with the ‘state of the world’ which occurs. An example of such a contract was discussed in section 2. There it was argued that the specification of such a contract would be enormously timeconsuming and complex. Ultimately, it would encounter the problem of ‘bounded rationality’; the sheer impossibility of imagining all the future contingencies which might arise along with the appropriate responses to them. We also noted that information about the ‘state of the world’ might be distributed asymmetrically between the contractors, thus leading to problems of ‘adverse selection’ and ‘moral hazard’.

3.3.Sequential spot contracting

Instead of a single contract, deterministic or probabilistic, involving commitments in future time periods, the parties involved in a project might contract period by period. As time gradually reveals what has to be done, the contracts are drawn up and the specified tasks are accomplished in a sequence. This solution faces the objection emphasised by Coase that the number of contracts required to accomplish a given objective will be very large if they are continually renegotiated over time. The number of contracts, however, will not be the only problem. An equally important issue is the cost of establishing each one. In principle we might imagine the process of recontracting as a relatively simple operation. The buyer of labour services, for example, would ask a worker to do something at the established wage rate and acceptance of this ‘request’ would imply that the ‘contract’ had been duly renegotiated. According to this view, associated with Alchian and Demsetz (1972), the type of contract observed within a ‘firm’ is not a single long-term contract of employment involving ‘direction’ of resources by the buyer, as claimed by Coase. Instead, there is an implicit process of continual renegotiation as in a system of sequential spot contracting.

3.4. The contract of employment

Where the process of recontracting operates as smoothly as suggested above there would be no advantage attached to a contract of employment. Indeed, it would arguably be extremely difficult in practice to distinguish between the two methods of contracting. Whether an ‘employee’ is considered to ‘renegotiate’ his or her contract continually, or is seen as accepting contractually permissible ‘instructions’, may not in some circumstances be a matter of very great practical importance. Analytically, however, the distinction is significant. The Coasian view of the employment contract requires that it is possible to specify a list of ‘acceptable’ tasks from which the employer can choose. Any attempt at such exhaustive listing must, however, confront the information problem. The employer simply will not have sufficient knowledge to draw up a contract of this nature. If, on the other hand, information is revealed gradually over time, and if, further, this information accrues not to everyone equally but to particular individuals (it is ‘impacted’, to use Williamson’s jargon), the crucial problem will be to set an environment in which people have an incentive to act cooperatively rather than opportunistically. Thus the employer is not a giver of instructions, as in Coase’s model, but a provider of incentives. The employee becomes not a passive receiver and executor of orders but an active agent of the employer.

3.5. The agency contract

Under an agency contract, one party (the agent) agrees to act in the interests of another party (the principal). The example of the architect and person A has already been discussed earlier in this chapter. Note that two important features are required to hold if the agency relation is to be interesting. Firstly, there must be a conflict of interest. The architect, by assumption, was interested in giving A’s plans the minimum amount of attention he or she could get away with. Person A, of course, was interested in eliciting from his architect the greatest attention that was possible. Secondly, there must be an asymmetry in the information available to principal and agent. Person A may simply not know what actions are possible and how they may affect him. He may not be in a position even to tell what action if any, his agent has taken.

Clearly if there were no conflict of interest, the existence of asymmetric information would not matter. The agent would always choose an action which accorded with the preferences of the principal. Similarly, if the information available to both principal and agent were the same, the conflict of interest would not matter since the principal would immediately detect any ‘opportunistic’ behaviour on the part of the agent. Where both asymmetric information and conflict of interest are present, the problem facing the principal will be to present the agent with a ‘system of remuneration’ sometimes called a ‘fee structure’ or ‘incentive structure’, which will provide the principal with the greatest payoff.

In the case of the relationship between employer and employee, there are obvious parallels with the principal-agent problem. This was recognised by Coase, who, in a footnote in his 1937 paper (p.337), wrote:

Of course, it is not possible to draw a hard and fast line which determines whether there is a firm or not. There may be more or less direction. It is similar to the legal question of whether there is the relationship of master and servant or principal and agent.

The clear implication here is that only a contract of ‘master and servant’, which implies the direction of resources, will be found in the Coasian firm. The relationship of principal and agent would not be compatible with the existence of a ‘firm’. More recent theorists would not accept this judgement. Once the problem of asymmetrically distributed knowledge within the firm is recognised, together with the accompanying possibility of moral hazard, it becomes useful to view the employee as an ‘agent’, and the firm as a response to the agency problem. The Coasian insight that the firm replaces a whole system of multilateral contracts with bilateral contracts between employer and employee is maintained, but the nature of the contract between employee and firm is no longer seen exclusively in terms of the direction of resources. Whatever the strictly legal position, the economist can argue that perceiving the relationship between ‘firm’ and employee in terms of principal and agent may provide valuable insights into the way resources are allocated within the firm.

3.6. Relational contracting

All of the contractual forms discussed above have one thing in common. The agreements are all well specified and complete. In the spot contract, the deterministic contract, the state-contingent contract, the agency contract or even the Coasian employment contract, the obligations of each of the parties under the contract are clear. An instruction under a contract of employment is either permissible or not. The quality of a product or service traded in a spot contract is clear and unambiguous. The agent’s fee will be related to results which will be easily observed by both parties while actions may not figure in the contract at all (in a sense, all lawful actions of the agent would then be contractually permissible).

In practice, of course, things are never that simple. As we emphasised in Chapter 1, the firm is a device for handling change and coping with the problem of lack of trust. The essence of the firm from this point of view is not simply that it involves fewer contractual linkages than would the market, or even that dealings are repeated period by period. The main point is that bounded rationality inevitably implies that contracts will be incomplete, and incomplete contracts are vulnerable to opportunism. Williamson (1985) is particularly associated with this view.6 The contracts discussed above were all from the world of ‘classical contracting’ in which clear agreements could be formulated and, if necessary, enforced by an outside agency (the state). There are many circumstances, however, in which such enforcement mechanisms will be ineffective and the contractors themselves will have to develop a system of ‘governance’. The firm is then a system of governance for incompletely specified contracts. It establishes a framework in which the benefits from a continuing association can be achieved. Because potential conflicts will inevitably arise over time, procedures are devised to minimise their destructive consequences and induce as much cooperative behaviour as possible.

Contracting within the firm is not ‘classical’ but ‘relational’. Implicit exchanges are going on continuously, but they are not formalised in specific ‘contracts’. People are cooperative because they perceive it to be in their own long-term interests and because they come to trust the governance structures of the firm. Williamson emphasises that governance arrangements within the firm will not always be necessary. Where, for example, very specific services are required of someone at a particular point in time, and the quality of these services is easy to define and assay, there is no advantage to establishing a specialised ‘governance structure’. The spot market is the arrangement which minimises the cost of the transaction. Even where a continuing association is desirable, a firm may not evolve. Repeat dealing is a perfectly reasonable way of establishing trust and reputation in some market settings, as was seen in Chapter 1. The crucial element, for Williamson, is vulnerability to opportunism deriving from the existence of transaction-specific assets.

As explained in section 2.4, a provider of a service may gain knowledge and experience over time which is specific to a particular buyer. A workforce in a firm can also accumulate similarly specific skills. This is not, of course, undesirable in itself. The problem is simply the transactional one that continual renegotiation of contracts in these circumstances puts the employer in the sort of position faced by person A in our example of the building project. Each person with whom he or she is negotiating is in the possession of skills and information which he/she does not fully share. Further, once individuals or groups of individuals are more productive within the firm than they would be outside, the income generated by their efforts is a form of ‘rent’. Striking a bargain is then inhibited by asymmetric information and there is an incentive to act ‘opportunistically’ in pursuit of these ‘rents’.7

For Williamson (1985), therefore, special governance arrangements within the firm develop when specific assets require protection which classical forms of contracting cannot provide. Frequency of repeat dealing is still important, both because it is repetition which generates transaction- specific knowledge and because infrequent dealing would not warrant the development of an expensive governance structure. Further, an ever- changing and uncertain environment favours the evolution of a firm because in very stable and unchanging circumstances, trust engendered by repeat dealing might be a cost-minimising response. Thus, frequent contracting with highly transaction-specific resources in an uncertain environment leads to the evolution of ‘unified governance’.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

Enjoyed looking at this, very good stuff, appreciate it.