The effective management of office personnel, as with other groups of employees, is very much influenced by whether staff feel they are fairly and equitably treated, particularly in regard to pay scales relative to the type of work they do and the personal effort they put into their work.

1. Job Evaluation

Because of the discrepancies in pay rates and status within an organisation, frequently the cause of staff dissatisfaction, the process of job evaluation has been evolved.

The first step in this procedure is job analysis, the technique of obtaining detailed facts about each job and the tasks it involves. Two assessments can then be drawn from these facts, the job specification and the job description, already described in Chapter 15. The second step is to determine the relative values of all jobs one with another. From this analysis the jobs can be evaluated and listed in order of value to the organisation, and pay scales established accordingly.

Salary scales and individual enhancement are dealt with by the techniques of job grading and merit rating.

2. Job Grading

This involves the determination of the contents of each job and its classification according to the skill, knowledge, experience and degree of responsibility required. The Institute of Administrative Management has adopted the following scheme which has gained wide acceptance.

Grade A: Simple tasks under close supervision, requiring no previous experience (messenger work, sorting).

Grade B: Simple repetitive tasks requiring short training and performed under close supervision (indexing, simple copying).

Grade C: Work of routine character requiring reasonable experience and/or special aptitude (ledger clerk, key-punch machine operator: checking grade B work).

Grade D: Work of considerable experience but limited initiative, needing little supervision (shorthand-typist on non-routine work). This is the pivoting grade between clerical and supervisory jobs – usually the province of adult clerks.

Grade E: Work requiring a significant amount of initiative and discretion, or specialised knowledge and responsibility (lower-grade supervisors over small groups of staff; possibly a personal secretary).

Grade F: Work requiring a great measure of responsibility and liaison with management, or the application of some professional knowledge or techniques (typing pool supervisor, assistant accountant controlling a small group of accounts clerks).

Grade G: Work requiring a greater measure of expertise than that of Grade F, to the level of a first degree or the later stages of a professional qualification such as Chartered Secretary, membership of one of the bodies of accountants or of the Institute of Administrative Management (assistant company registrar, assistant accounts manager, credit controller).

Grade H: Tasks requiring a higher degree of knowledge and expertise than those in Grade G, demanding a full professional qualification or an academic degree backed by a significant amount of experience. A considerable amount of judgement and expertise is required ; exercised in complex and important work (supervision of not less than 20 workers, assistant company secretary, accounts manager, legal assistant).

The examples given in brackets are suggestions only of the types of jobs that may be found within each grade. It is important to remember, however, that the work level and responsibility of any job may vary according to such factors as the size of the organisation and the size and make-up of individual groups: thus jobs graded E in one undertaking may warrant grade F or even G in another. Job titles also need careful examination as the same title may be applied to different jobs in different organisations.

Job grading requires the careful assessment of tasks; it is not at all easy but must be done objectively, remembering that it is the job that is being graded and not the occupant of the post. One method is to give points to each attribute in the job specification, weighted to their relevant importance, and fix the job grades according to the ranking totals.

The number of job grades must not be too many or the distinctions will be too fine and the scheme may be too difficult to apply. On the other hand, too few grades result in wide gaps which are difficult to bridge. The Institute of Administrative Management, one of the foremost authorities on clerical job grading, suggests eight, as can be seen above, to cover the work levels from the most junior office worker up to departmental manager. However, once an effective job grading scheme has been devised it is usually easy to fit new jobs into it as they arise provided proper job specifications are constructed.

Job grading may be said to have the following advantages:

- Management has to acquire a better knowledge of job content than might be had without job grading.

- Because of 1 there is a better recognition of training requirements.

- It assists in staff selection.

- Workers know where they are in the staff hierarchy. This improves inter-staff relationships and staff/management relationships, thus raising morale.

- It minimises pay anomalies and pay disputes.

- It assists in the formulation and operation of promotion schemes.

- It tends to reduce staff turnover.

- It helps in establishing salary rates for new jobs.

- It is useful in estimating administration costs and formulating administration budgets.

There are, inevitably some limitations to job grading. The most important of these are:

- The evaluation of jobs must remove subjective judgement and there can be borderline judgements that are difficult to place in the right grade.

- This can also lead to anomalies in the grading within an organisation unless care is taken to identify anomalies and change them where possible.

- In itself it takes no account of an individual’s performance, and this often needs to be accounted for in other ways.

- Job content may alter in the course of time and existing gradings may become unrepresentative; therefore it is important that a review takes place periodically.

- There is a need to avoid the possibility that the worker may be graded instead of the job.

- Internal job grading must also be able to relate to external conditions in the determining of salary scales.

Whilst job grading is useful in establishing the relationship between different clerical jobs and hence their points on the salary scales, it takes no account of the varying performances of different clerks doing the same work within the same grade: in other words, it takes no account of individual effort. This aspect of staff management is dealt with by merit rating.

3. Merit Rating

This seeks to reward, or otherwise, workers within the same job grade in relationship to their personal performances, and is the reason there is a band of possible salaries at each grade. Various methods are employed for merit rating, there being no hard and fast method. It must be remembered however, that although job grading is based on subjective judgement the grades give a reasonably objective structure in which to place jobs. In contrast, merit rating, being based on supervisor observation, is largely subjective.

The qualities looked for in a worker’s performance for merit rating within the job grade can be given primarily as:

- How well the work is done – that is, its quality.

- Volume of output, or quantity of work.

- How cooperative the worker is, both with supervisory staff and with colleagues.

- How reliable, dependable and loyal the worker is.

Other aspects of performance may also be taken into account, however, such as punctuality, display of initiative and so on.

The Institute of Administrative Management recommends five ratings within each job grade and these are set out below:

- This covers newcomers and those just promoted to a grade. It also includes the training or learning period and represents the standard of efficiency to be expected at this juncture.

- This rating is used when the worker has attained proficiency in the job and can be expected to carry out the normal aspects of the job adequately.

- This rating is applied when the worker has acquired sufficient knowledge and experience to deal with any eventuality likely to arise.

- This rating covers those workers who perform in a noticeably superior manner, beyond the performance expected of an ‘experienced’ worker. The standard is that of a learner in the next superior grade. A clerk attaining a ‘superior’ rating would be one suitable for promotion.

- This rating is applied to a worker whose performance is outstanding and is commensurate with the ability of a qualified clerk in the next superior grade. Normally this rating is confined to those workers who warrant promotion but for whom no immediate vacancy exists.

The principal benefits accruing from merit rating are:

- It recognises ability in individual workers.

- It assists in the implementation of the promotion policy.

- It provides an incentive to employees to improve their performance and so increase their earnings.

- It draws attention to unsuitable or insufficiently trained personnel so that remedial action can be taken to ensure the worker concerned can be made a more useful member of the office team.

- It helps to ensure that qualifications and job requirements match. This assists in avoiding the situation in 4.

- It allows for fine tuning of salaries within the broad bands of job grades.

Some of the disadvantages may be stated as:

- Because of its subjective nature there may be inconsistencies in the ratings.

- Supervisors may be too busy to study the performance of their staff sufficiently and may therefore make superficial, and sometimes unfair, judgements.

- Favouritism on the part of the supervisor may produce unjustifiably high ratings; prejudice may, equally, depress ratings.

- Unless they are carried out frequently ratings may not reflect current performance.

4. Staff Appraisal

In order to ensure that the performance of workers is known and this information is maintained some form of staff appraisal may be established. This can vary from an informal and often infrequent assessment of how each member of staff performs to a formal and structured scheme where assessment is carried out at regular intervals such as every six months or annually. The larger and more diverse the organisation the more likely it is that staff appraisal will be carried out within a formal system.

The more formal merit rating assessments are made by using various types of rating scales, of which the most used are as follows:

- Adjectival: This is a descriptive assessment (very good; average).

- Numerical: This uses numbers instead of descriptions (1 = superlative, 2 = superior and so on).

- Literal: Letters of the alphabet are used instead of adjectives or numbers (A = A = superlative, B = superior and so on).

- Descriptive: The qualities being assessed are given detailed descriptions and are set out in tabular or list form: the items are ticked by the assessor as required.

- Percentile: Assessments are expressed as percentages or by points.

- Ranking: This method lists, or ranks, workers in order of merit.

Normally assessment is carried out by the immediate supervisors of the staff concerned, who report to their immediate managers. This is because

only a worker’s immediate supervisor is aware at first hand how the job is being carried out and what approach the worker has to it. Often, to try to avoid bias, either favourable or prejudiced, an appraisal form has to be completed on which the various qualities of performance are set out with spaces for noting responses according to the rating scales mentioned above. These forms are then examined by either one senior manager whose duties include personnel management, or a merit rating committee charged with the function of establishing the ratings for each employee. Normally each employee will be interviewed by the supervisor, the manager or the committee. Discussions will take place between the seniors and the final assessment will be decided. In some cases the employees themselves may be asked to contribute though this is not, at the moment, common.

There is some controversy as to whether staff should be made aware of their ratings. Whilst is can be argued that this information may lead to discontent between members of staff and even discourage those having disappointing ratings, it must also be submitted that workers have a right to know their assessments – indeed, may expect to know them – and that this information, diplomatically put, will stimulate staff to improved performance.

5. Salary Scales

Ideally salary scales should be based on job gradings as this is, after all, one of the reasons for establishing the gradings. However, there are other factors that enter into the fixing of basic remuneration. It could be said that workers normally require a reasonable salary plus good working conditions, reasonable security and job satisfaction. If reliable, efficient workers of good morale are to be attracted and retained generally speaking all four attributes must be present. According to age and temperament, however, some workers will accept (a) poor conditions, poor security and low job satisfaction for a high salary, or (b) good conditions, absolute security and reasonable satisfaction for a poor salary – and, of course, computations of these factors.

Generally speaking, the market (that is, what other employers are paying) will determine the minimum basic salaries but more recently, in many industries and in the public sector, trade union power has a great influence on what workers will accept. Though not so strong among clerical staff as among industrial workers, nevertheless in many cases the trade unions must be reckoned with.

From the employer’s point of view salaries are largely determined by:

- What the organisation can afford.

- What other organisations are paying.

- The organisation’s employee/employer reputation (this often determines the number and quality of people applying for jobs and hence the initial salaries that have to be offered).

Staff, however, are concerned with other aspects of their pay, the most important of which are:

- The actual gross pay.

- Take-home pay (the actual pay received in the pay packet or on the pay cheque).

- Real pay (actual purchasing power, which includes the so-called fringe benefits such as subsidised meals, cheap loans, use of a car and so on).

Salary scales are made up of basic pay plus margins for age and skills. The job grade fixes the basic rate and merit rating is used to fix the enhancement for skill and experience. The addition for age is a problem. It is customary among young members of the staff to have age salary scales in conjunction with grade scales. Thus junior staff may have ‘birthday’ rises apart from other considerations. With very junior staff – say, within two or three years of leaving school – two increments a year are preferable and provide an incentive to the members of staff concerned. In addition, many organisations give long-service bonuses as an encouragement for workers to stay with the undertaking.

Yet again, it is common in many organisations, especially in the public service, to give yearly increments within grades: these are often construed as a kind of merit rating addition on the premise that within a limited period each year’s experience brings with it greater competence and efficiency.

Grade scales are established in bands with a lower and upper limit to each, the band width allowing the addition of merit increases to the lowest basic rate. Some such scales provide for each succeeding grade to start at the point where the lower one stops as:

Grade A £A to £D

Grade B £D to £G

Grade C £G to £J

and so on. However, in order to give particuarly good workers in one grade extra benefit over poor workers in the next higher grade, and to provide incentive where promotion is warranted but not immediately possible, it is preferable for the scales to overlap thus:

Grade A £A to £E

Grade B £D to £H

Grade C £G to £K

and so on.

6. Incentives and Motivation

The questions of incentives and motivation are very important indeed and it is possible only to touch briefly upon the subject here. The difference between incentives and motivation should be clearly understood. In short, incentives can be said to comprise those influences that encourage greater effort and are external to the worker – for example, bonuses, commission, additional holidays, promotion and the like; in other words, chiefly material advantages provided by the employer and mostly financial or financial equivalents. Motivation on the other hand, derives from the worker’s own attitudes and is encouraged by good staff/management relations, status, allowing the use of personal initiative and, frequently, the participation of workers in management decisions affecting their jobs and working environment.

Essentially it could be said that incentives arise from outside the individual and are, in the main, materialistic and motivation springs from within and is related to attitude and self-discipline. This is not to say that the office administrator and management generally cannot motivate workers: they very definitely can by pursuing sensible personnel policies, giving a measure of personal control over work, allowing a measure of initiative to be used, encouraging staff to identify themselves positively with the organisation and by establishing working practices that seek to provide job satisfaction.

The usual forms of incentive are based on payment for increased output, an example being bonuses earned by typing staff for work done over and above an agreed standard volume. Such incentive payments can be applied individually or on a group basis. There are, however, other forms of incentive not necessarily tied to output, an example being an attendance bonus for satisfactory prompt attendance, sometimes applied where punctuality and attendance have become slack and have therefore become a problem.

It will be seen that such incentive payments relate only to performance that can be measured and compared with previous performance. Often such an approach is not possible: for instance, it is impossible to expect a telephone sales order clerk to increase incoming customers telephone calls. In these cases some other means of stimulating productivity must be found, such as payments related to profits or to the activities of a widened group. In the example given the sales clerks could be paid bonuses in relation to the sales orders obtained by the sales representatives they service. The aim of this would be to use the telephone more efficiently, perhaps by cutting down the length of calls, and so increasing the number of calls dealt with which, in turn, would help to enhance the sales representatives’ effectiveness. What is certain is that if incentive payments are made to one section of the office staff (where output can be measured) some similar provision must be made in other areas where measurement is impossible or particularly difficult; otherwise resentment will be generated.

When applying incentives the following points must be observed.

- The basic salary scale must be adequate.

- The incentive scheme must be easily understood.

- The incentive scheme must be patently fair to all.

- The incentive scheme must have the willing agreement of all concerned.

The question of motivation is much more difficult than that of incentives. Much work has been done in this area by researchers such as A. H. Maslow, D. M. McGregor and F. Hertzberg, to name only three whose findings have had a great influence on much management thinking. Because human behaviour is so unpredictable it is not possible to lay down hard-and-fast rules that will solve the many problems of motivation in all cases. Some of the solutions advocated, however, are set out below.

6.1. The working atmosphere

An atmosphere of mutual trust and respect must be generated between staff and management. The authoritarian style of management is no longer acceptable to workers and, without relinquishing their overt authority, supervisors and managers must seek the cooperation of their staff rather than impose what might be seen to be their autocratic will. This entails involving staff in any discussion and decision-making that affect them as individuals. A certain indicator as to whether this has been achieved is whether the staff in discussing their organisation, refer to ‘we’ rather than ‘they’.

6.2. Involvement

This arises out of the above. It is now widely accepted that workers have a right to participate in decisions concerning their working conditions. This can mean simple participation in informal talks or can go so far as the setting up of formal joint consultative committees of management and staff representatives. It is essential that management is seen to take staff involvement seriously, or resentment and lowered morale will result – the opposite to what is intended.

6.3. Recognition and status

Human beings need the esteem of other human beings and need to have their efforts recognised and appreciated. Managers must be aware of these needs and take pains to recognise staff as people and not treat them just as working units. Praise and encouragement should be given where justified.

Similarly, the status of individual workers must be recognised as it reinforces the self-esteem so essential to good morale. However, there is a trap here that the office manager must beware: giving a title for status without the commensurate responsibility or authority very soon causes dissatisfaction: an ‘empty title’ soon results in loss of self-esteem and loss of the esteem of the worker’s colleagues – a sure recipe for reduced motivation.

6.4. Job satisfaction

A monotonous job soon becomes a boring job. Staff engaged in such work derive little satisfaction from it and more often than not lose any positive motivation they had when they began. Job satisfaction can be increased by increasing the job content or by extending the range of operations that a worker performs. The first is termed job enlargement and an example would be allowing a telephone sales order clerk to follow up customer queries and even to see customers who call rather than have these other tasks done by other people. The second is called job enrichment and entails involving the worker in other tasks associated with the job: an example would be to allow the telephone sales order clerk to price and extend orders received and, perhaps, to check creditworthiness.

Unfortunately, schemes for job satisfaction can increase costs, but they are often considered worth the additional expense because of the improved staff morale and motivation they produce.

7. Staff Welfare

The welfare facilities available to staff can have a great influence upon their attitudes and morale, and provision of these facilities has proved to be an important factor in staff/management relations. Provision can range from the simple supplying of tea and/or coffee morning and afternoon (nowadays increasingly available from vending machines) to the availability of a full canteen service with subsidised meals. Where physical considerations preclude a canteen, luncheon vouchers are often provided. Other welfare facilities include the provision of a sick room with nursing staff, medical benefits such as free membership of one of the private health schemes and the provision of sports facilities. What is offered in the way of welfare provision is dependent upon the size of the organisation as a whole, the size of the unit involved and the attitude of management.

8. Staff Promotion

There is little doubt that one of the most effective ways to provide both incentive and positive motivation is that of possible promotion. Whilst there are, of course, workers who have limited ambition, or none at all, many look forward to eventual promotion both from the point of view of increased earnings and of the improved status and higher esteem that accompany promotion. It is, therefore, of importance to an organisation that there is a fair and sensible promotion policy, known to all relevant staff. Such a policy has other benefits than that of engendering good morale: it assists the planning of the organisation’s human resources and induces valuable members of staff to stay with the organisation rather than seek new employment elsewhere where the training and experience they have acquired will be used to another concern’s advantage.

There are two general approaches to the filling of senior and semisenior vacancies:

- Promotion within the organisation from existing staff.

- The engaging of recruits to these positions from outside.

Internal promotion can be based on seniority – that is, length of service – or on observed ability or, of course, on an amalgamation of both.

External recruitment is not really promotion but is very relevant to a promotion policy and so must be examined. The advantages of this procedure may be said to be:

- It brings in fresh ideas and stimulates new thought on existing problems. Where no new blood is ever recruited an organisation stands in danger of perpetuating old ideas and of stagnating.

- It can stimulate existing staff to greater effort to fit themselves for promotion in the future.

Against these disadvantages must be set the following possible disadvantages.

- Instead of stimulating existing staff, resentment can build up that outsiders are taking the well-paid and responsible jobs which staff consider their own right.

- It takes longer, and is therefore more expensive, for outsiders to acclimatise themselves to their new working environment and the accepted practices of the organisation. They may also find existing staff, at least at first, resentful and uncooperative.

- It is highly likely that the salaries offered to outsiders have to be higher than those paid on internal promotions, and if this becomes common knowledge existing staff on the same grades could become discontented.

It is obvious that a policy of internal promotion, except in special circumstances, is generally speaking accepted to be the sensible course and this is the policy of most large organisations. Such a course encourages a sense of security in staff and an expectation of reward for services rendered. From the undertaking’s point of view it helps in formulating manpower planning and training programmes, ensures in the main a continuity of staffing and assists in establishing regular salary scales. In some areas, such as those where staff are in constant touch with customers, suppliers and so on it avoids the breaks in continuing personal relationships that occur when new personnel from outside are introduced. On promotion an existing member of staff rarely ceases external contacts abruptly. This aspect of the promotion programme is especially important in the sales and purchasing departments and, to a slightly lesser extent, in the accounting area.

8.1. Promotion by seniority

Seniority alone is not the best reason for promotion though it is a policy that has been followed in the past by most organisations. It is regarded as a reward for long and loyal service, it claims to make the best use of experience and is said to maintain high morale. It is also said to reduce labour turnover because it induces a feeling of security in staff. On the other hand, it could also be said to stifle new ideas and lead to the perpetuation of out-of-date practices. In addition, of course, it can lead to eager, able and valuable younger members of staff seeking promotion elsewhere and so lose to the undertaking potentially capable and efficient seniors. This, in turn, results in only the least able remaining on the staff to the ultimate disadvantage of the organisation.

8.2. Promotion by ability

From the point of view of the financial health and operating efficiency of the organisation, promotion by ability is the most inviting course to adopt. This means that an adequate supervisory and management training programme must be provided and that an effective staff appraisal scheme is introduced and pursued. However, it must also be recognised that in the minds of most employees length of service should be taken into account for promotion, which leaves us with the situation that whilst ability must be the prime factor for promotion in most cases seniority must be taken into consideration as well, other things being equal. Any member of staff passed over in this context must have the reasons fully explained and accepted to prevent resentment arising which might affect future performance and attitudes.

Two things that are often forgotten in the pursuit of a policy of internal promotion are:

- Promotion is based on past performance with the expectation that like performance will continue into the future. This may or may not occur as the person’s attitude may change with more authority: careful attention must, therefore, be attached to personality and temperament.

- It is sometimes difficult for staff members to accept the authority of someone they have worked with on equal terms for a long time. There is a lot to be said for promotions at lower levels to be into different departments or with different groups. The person promoted may also find it embarrassing or difficult to exercise authority over his erstwhile peers.

Whatever promotion policy an organisation decides upon it is essential that it is known to all staff and seen to be fair so that no resentment is engendered in its application.

9. Staff Discipline

The question of staff discipline in a modern industrial society is a vexed one. Workers are no longer willing to accept the penalties formerly levied when management could be more autocratic, and fines and similar pecuniary penalties are difficult, if not impossible, to enforce. Even given that clerical workers are not generally under the wing of a strong trade union, they would still resist and resent having, say, a quarter of a day’s pay withheld because of lateness, or a day’s pay for an unauthorised day’s absence. Persistent lateness or persistent unauthorised absence might call for the clerk’s dismissal, but otherwise admonition and friendly reason are the main tools an office administrator has. In fact, satisfactory discipline is achieved principally by good management/staff relations.

10. Staff Dismissal

Where a member of staff has to be dismissed this action must be carried out within the provisions of the service agreement, and the right length of notice must be given. Where the length of notice is a month or more it is often preferable to pay money in lieu of notice: it can save a certain amount of embarrassment because of the employee’s continued presence and it gives the worker concerned more free time to look for another post. Where no express condition exists as to notice then what is customary in the trade of profession will obtain. However, it must be remembered that, in Britain, minimum length of notice is governed in most cases by legislation.

Dismissal must always be fair and be seen to be fair: otherwise it may have an unfortunate effect on other staff and their morale. In Britain there is legislation which gives an employee the right to make a claim for unfair dismissal if discharge is alleged to be unjustified, the principal Act being the Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act, 1978. This Act also includes provision in regard to dismissal previously included in the Contracts of Employment Act, 1972, which was consolidated into the 1978 Act.

Instant dismissal – that is, immediate discharge without notice or payment in lieu of notice – is valid in special circumstances, but the employer must have sound and irrefutable evidence of misconduct to take such action, if no legal consequences are to result. The following activities on the part of a worker are considered to justify instant dismissal.

- Wilful misconduct whilst at work.

- Proven dishonesty.

- Gross negligence or complete incompetence.

- Actions in private life that may interfere with or bring disrepute to the organisation’s business or prevent the employee working normally. Such activities would include drunkenness, drug-taking and immoral behaviour. The status and kind of job of the offending employee will have a great bearing on whether such behaviour can be construed to be detrimental to the undertaking.

- Disobedience of a proper order to perform work that is within the terms of the employee’s contract.

- Disclosure of business secrets without permission.

- Violence or threats of violence to fellow employees.

- Unauthorised absence from work particularly if persistent.

Apart from those acts in 1, 2 and 6 the prudent employer would give warning of instant dismissal after the first offence had come to notice but would not actually dismiss at the first offence.

11. Staff Turnover

This comprises avoidable staff departures or severances and if high is expensive in cost and efficiency. Some staff turnover is necessary to prevent stagnation in an organisation, but this must not be excessive and can usually be put down to one or more of the following reasons.

- Poor supervision or supervision that is deemed by staff to be unreasonable.

- Lack of opportunity to progress.

- Poor working conditions,

- Poor or inequitable pay.

- Inadequate training, giving a sense of inadequacy.

- Poor staff selection.

- Business fluctuations.

- Health and safety hazards.

- Unfair distribution of work.

- Insufficient volume of work leading to boredom.

- Boring work owing to lack of variety in job content.

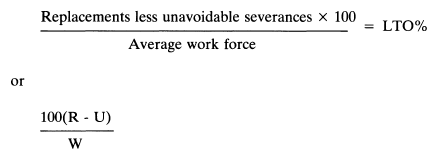

There is no standard procedure for assessing labour turnover but a commonly used formula is

Excessive staff turnover should be investigated. This is usually accomplished by attitude surveys which indicate the state of worker morale. Low morale almost invariably leads to a high labour turnover.

12. Attitude Surveys

A negative attitude to the organisation by its employees is a prime cause of inefficiency and of staff leaving, and the following factors influence this:

- The personality of the employee.

- The type of work and whether compatible with the person doing it.

- The working environment.

- External factors such as industrial unrest, trade recession and the like.

An attitude survey should be conducted by an impartial observer but this is usually not possible. It should not be carried out by anyone, however, who has worked in close contact with the employees concerned. It can be accomplished by:

- Interviews with staff personnel.

- A suggestion box, where contributions are anonymous.

- The establishment of a grievance committee.

- The circulation of a questionnaire, respondents being assured of anonymity.

- Interviews with members of staff leaving. This is, of course, too late for the persons concerned for corrective action to be taken. In addition, the reasons given for leaving may not be the true ones so such interviews must be conducted with much tact.

Whatever method is used it must be made quite clear that there will be no recriminations against any member of the staff and this undertaking must be strictly honoured. Among the questions likely to be asked might be:

- Do you like your job?

- Are your working conditions satisfactory?

- Would you leave if you could and why?

- Do you consider management treats staff fairly?

- Do you consider you are fairly paid?

and so on.

13. The Employment Life Cycle

This is the complete history of an employee from recruitment to retirement or other cause of the termination of employment. It is usual for organisations to keep running records of all employees and their employment life cycles. These records contain an analysis of all the stages in the employment history of each worker and include particulars of training, pay and pay increases, promotions, absence through sickness and other causes, as well as details of job grading and merit rating, performance appraisal, reprimands, attitudes and motivation. Thus an overall picture can be built up of the employee concerned, his or her progress and career potential and so give a guide to future training or educational programmes to enhance the worker’s value to the organisation and to his or her own personal career prospects. The last entry will, of course, be severance from the organisation and this should detail the circumstances obtaining for this, e.g. retirement, dismissal and why, leaving of own accord and so on. This complete record should be retained for some time as it would form the basis in case other future employers should seek references.

14. Supervisory Training

The efficiency of the office service and the morale of the clerical staff are influenced very considerably by the type of supervision provided. Supervisors, therefore, need training in modern supervisory techniques.

Normally an office supervisor would be trained on the job by assisting and sometimes understudying his or her superior, who may be the office administrator or a similar senior in authority. The supervisor of a typing pool, for example, may be attached to the manager of the secretarial services before taking over the typing pool entirely. It is essential that all supervisors are aware not only of their own area of work but also of the work of the other sections and departments with which their work relates.

The knowledge the competent supervisor needs to have or to acquire includes the following:

- How to delegate effectively.

- The problems of workflow and how to manage it to the best advantage.

- How to enforce discipline whilst earning and retaining the respect of staff.

- How to establish job priorities.

- How to develop a sense of anticipation so as to be prepared for eventualities as they develop.

- How to establish harmonious relations with staff without losing authority.

- How to develop human understanding.

External supervisory training is also provided by outside bodies such as colleges and private managerial schools, and various qualifications can be obtained in supervision which provide an incentive to study by the supervisor. At the same time these qualifications provide evidence of the attainment of a required standard.

15. Flexible Working Hours

Before leaving the subject of office personnel and its morale we must look at a fairly recent introduction – that of flexible working hours, popularly known as ‘flexitime’. This was devised with the purpose of giving office staff some freedom over their working day whilst maintaining an efficient office service. In essence it treats staff as adults with a responsible attitude to their work obligations instead of as clockwatching individuals anxious to do as little as possible. Where flexitime has been introduced the general opinion is that of high morale and improved staff/management relations.

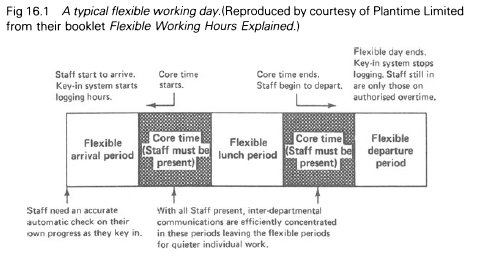

Essentially the office day is divided into five parts as illustrated in Figure 16.1. It will be seen that there are three flexible periods and two core (or fixed) periods. The core periods require compulsory attendance by all staff and the actual starting and finishing times of these will be determined by the demands of the organisation and the department concerned. The flexible periods allow staff freedom to choose (a) when to arrive, (b) the length of their lunch breaks and (c) when to finish, with limits on the first arrival and last finishing times and the period during which the lunch break may be taken. The practical application of this system can best be illustrated by a set of specimen rules as follows. (Reproduced by courtesy of Plantime Limited from their booklet entitled Flexible Workmg Hours Explained.)

Flexible Working Hours Rules

FWH is a system whereby you are able to choose (within certain limits) the time you start and finish work. It is not necessary to work the same hours every day, although it is important that the efficiency of the department does not suffer. You may build up a credit of hours over and above your standard contracted time or a debit, as long as these do not exceed the figures stated in the rules below.

Bandwidth: The earliest starting and the latest finishing times Monday – Friday (e.g. 8.00-18.00).

Core Time: The periods you must be in the office, except for authorised absences (e.g.10.00 – 12.00 and 14.00 – 16.00).

Flexible Time: The periods within which you may vary your starting and finishing times (e.g. 8.00- 10.00 and 16.00 – 18.00)

Fig 16.1 A typical flexible working day.(Reproduced by courtesy of Plantime Limited from their booklet Flexible Working Hours Explained.)

Flexible Lunch Time: Lunch breaks must be taken between e.g. 12.00 and 14.00. The minimum break you can have is e.g. 30 minutes, i.e. your contracted hours, e.g. 37^ hours per week or 150 per 4 weeks.

Standard Time: i.e. your contracted hours, e.g. 37½ hours per week or 150 per 4 weeks.

Debit Hours: The number of hours worked less than the standard time. You will be allowed a maximum of e.g. 8 hours at any time during the 4-weekly period.

Credits: The number of hours worked in excess of the standard time. You will be allowed a maximum of e.g. 8 hours at any time during the 4-weekly period.

Carry Over: At the end of the 4-weekly period any credits or debits will be carried automatically over to the next period. Any credits over the 8-hour limit will be queried and normally lost. Debits over the 8-hour limit will be taken as absence without permission.

Flexi-Leave: This is obtained by accumulating credit time and may be taken with management’s permission in whole or half days. Up to a maximum of e.g. 1½ days’ flexi-leave may be taken in any one e.g. 4-weekly accounting period.

Absence from Work: Authorised absence (due to holidays, sickness, business, etc) will be credited to you and updated into the FWH system to keep your account of hours correct. Medical appointments should be made during flexible time unless prior permission is obtained.

Overtime: Overtime will be authorised and recorded as normal; it is completely separate from FWH. Overtime will only start inside bandwidth if you have already completed a standard 7~-hour day. It will not normally be allowed if you are in debit.

From these rules it will be seen that the total weekly hours of staff are maintained and that a reliable control must be installed to ensure the accurate recording of times worked so that the system operates fairly and economically. Whilst the office administrator may feel able to institute a system of flexible working hours himself, it has proved in practice that this is really a task for the expert and experienced, owing to the number of unforeseen difficulties that can arise. The prudent office administrator would be well advised, therefore, to seek the assistance and advice of firms or consultants who specialise in this form of working.

The suggestion to install flexible working hours may come from the staff or from management: in either case it must be carefully discussed and agreed by both parties before any steps are taken. It must never be installed in the face of resentment or mistrust. This is particularly important because not all staff can be accommodated within a flexitime scheme. Some members, because of the nature of their work, must be on call during all the conventional office hours – say 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. or whatever is the traditional working day of the organisation concerned. For instance, people in constant communication with customers will be expected to be accessible at all times by those customers. On the other hand, this does not apply to a considerable proportion of the staff, such as invoice typists. This problem must be carefully handled so that those not benefiting from the proposed flexibility do not feel resentful.

Given a satisfactory agreement, the advantages and disadvantages of flexible working hours are claimed to be as follows:

To the employer:

- Staff gain a greater sense of responsibility.

- Work tends to be completed within the day as staff are more willing to stay and finish, thus building up credits, rather than carrying over unfinished tasks.

- If work does have to be completed on the day staff have been found to take credits rather than claim overtime payment; in other words, most people prefer time off to money.

- One-day absences drop in number. The reason for this seems to be that whereas under the conventional system an employee would rather report a day’s sickness than arrive late (where this is unavoidable) except for the obligation to arrive by the start of core time there is no such thing as a late arrival.

- The flexible periods tend to be quieter than the core times; thus there are specific periods in the day when it is easier to concentrate, which improves the quality and the quantity of work.

Against these advantages must be set the following:

- The initial cost of installing a system and getting it to settle down can be relatively high. There is also the continuing cost of maintaining hourly records, though this may be only nominal.

- There is additional cost in providing lighting and heating because of the extended day.

- Supervision must be provided over longer hours which may mean, in some flexible periods, interchanging supervisory staff for short periods and this may result in less technically expert supervision in some cases.

To the employee:

- The ability, within limits, of determining the working day.

- The ability to choose the easiest travelling times.

- The ability to fit in social activities more easily by accumulating credits.

- A sense of being treated as an adult and not as a clock-watcher. Against these must be set:

- Possible resentment of clocking on (however this is done), though this soon fades.

- Less possibility of earning overtime pay.

- The absence during a flexible period of a colleague may interfere with a job.

The essence of the successful introduction and operation of flexible working hours depends upon the following:

- Mutual understanding and agreement between staff and management.

- No reduction in overall work requirements.

- Effective control over attendance hours, particularly in the recording of credits and debits.

- Limitation on the total credits that may be accumulated during any stated period, such as over four weeks.

- Constant review of the working of the system to ensure staff satisfaction and avoid abuses.

Source: Eyre E. C. (1989), Office Administration, Palgrave Macmillan.

I like the efforts you have put in this, appreciate it for all the great blog posts.