1. HOW AND WHY ARE CAREERS CHANGING?

Many writers over the past decade have provided a picture of dramatic change in the nature of careers that are possible in today’s society. The traditional career within a single organisation, characterised by hierarchical progression, managed on a planned basis by the organisation, is gone, it is argued (see, for example, Arthur and Rousseau 1996a; Adamson et al. 1998). Organisations now have flatter structures and need to be flexible, fluid and cost effective in the face of an uncertain and unpredictable future. Thus they can no longer offer long-term career progression in return for loyalty, commitment and adequate performance, which was an unwritten deal and part of the traditional psychological contract.

Kanter (1989), for example, suggests that managers can no longer rely on the organisation for their career future and must learn to manage themselves and their work independently, as many professionals do. In particular, they must build portfolios of their achievements and skills, develop networks, make a ‘name’ for themselves and market themselves within the relevant industry sector rather than just within their current organisation. In a different sense Handy (1994) uses the words ‘portfolio career’ to mean ‘exchanging full time employment for independence’, which is expressed in the collection of different pieces of work done for different clients. Individuals starting off a portfolio career often continue to do some work for their previous organisation (on a fee-paying basis) and add to this a network of other clients. Arthur et al. (2005) describe the ‘boundaryless career’ as one which includes moves between organisations, nonhierarchical moves within organisations where there are no norms of progress or success, and moves into different careers as well as employment outside the organisation. Postorganisational careers (sometimes called post-corporate) were defined in the Window on Practice at the opening of this chapter; and protean careers, involving reinvention of the self and discovery, have probably best been described by Hall (2004) who identifies such as career as bound up with the development of the self, driven by the individual’s values and self-fulfilment.

There is some debate, however, about whether portfolio and associated careers are liberating or exploitative (see, for example, Smeaton 2003), and the extent to which individuals have sought such careers or found them to be the only alternative may have some influence on their perceptions of this. Interestingly Fenwick (2006) in a study of nurses and adult educators who had become portfolio workers, found that such careers were simultaneously liberating and exploitative, partly due to individual desires for both contingency and stability.

The evidence to support the reality that careers have fundamentally changed is ‘shaky at best’ (Mallon 1998) and Guest and McKenzie-Davey (1996), for example, found the traditional organisation and the traditional career ‘alive and well’ (pp. 22-3), with the hierarchy still used for motivation and progression. However, there is increasing evidence over the past five or so years that professionals, in particular, are moving into selfemployment or agency work (see, for example, Purcell et al. 2005). As yet there remains insufficient research into the extent to which new career patterns are developing, for whom, and the mechanisms by which individuals are pulled or pushed into them.

Some argue that the contradictions between the above views are a result of people being in transition (see, for example, Burke 1998a), whereas King (2003) suggests that the ‘new career’ may be reflected in people’s expectations rather than their labour market experiences. Another explanation may be that temporary work and contract work are spread more evenly across different sectors (see, for example, Burke 1998b), and have therefore become more visible. Let us not forget that the traditional psychological contract was never available to everyone. Smithson and Lewis (2000) argue that public perceptions of increasing insecurity may have more to do with the characteristics of those whom the insecurity now affects, such as graduates and professional staff, than with an increase in the phenomenon. Similarly, different groups have different sets of expectations and subjective feelings of job insecurity. Younger workers accept insecurity, almost as the norm (see, for example, Smithson and Lewis 2000), but older workers feel the psychological contract has been violated. Older workers may have the same expectations as before but realise that the employer is no longer going to fulfil their part of the bargain (see, for example, Herriot et al. 1997; Thomas and Dunkerley 1999).

A different explanation for these contradictory findings is that organisations project the image of a stable and predictable internal career structure, because it is in their interests to do so, whatever the reality. Adamson et al. (1998) suggest that it is in the organisation’s interests to maintain the illusion of such career structures so as to retain high-performance employees. It could also be argued that such structures are useful in recruiting highly skilled employees, for whom career structures are likely to continue. Purcell et al. (2003) also showed that positive perceptions of career advancement opportunities are one of the most powerful determinants of employee commitment. However, if this is an illusion such a strategy may well backfire.

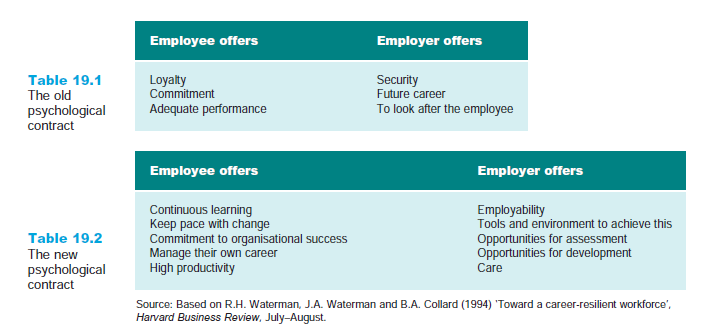

If the psychological contract between employer and employee now needs to be renegotiated, this does not mean abandoning the concept of career, rather, the idea of a new psychological contract is developing. Many articles identify a ‘new psychological contract’ in which the deal between employer and staff is different but still mutually beneficial. Employees offer high productivity and total commitment while with their employer, and the employer offers enhanced employability rather than long-term employment. The offer of employability centres on enabling employees to develop skills that are in demand, and allows them opportunities to practise these and keep up to date. This equips the employee with the skills and experiences needed to obtain another appropriate job when he or she is no longer needed by their present employer (see, for example, Waterman et al. 1994). The differences between the old psychological contract and the new, as they relate to careers, are shown in Tables 19.1 and 19.2. King (2003) found that graduates rated the offer of employability as of most importance in career terms, and they still expected the organisation to provide a career for them; she argues that the picture presented is one of lip service and a less than whole-hearted commitment to the concept of the ‘new career’.

However, a further contradiction is apparent in the literature: the assumption that the ‘new psychological contract’ supplants the old when the original contract is violated, but the degree to which this happens is debatable (see, for example, Doherty et al. 1997). Herriot (1998) argues that the new psychological contract is just more rhetoric, and that in reality there are many different new deals, and Sparrow (1996) suggests that the solution to the fragmentation of the old psychological contract is a series of layered individualised career contracts. King also suggests that the organisation should not adopt an either/or career approach, but aim to offer both internal careers and employability support.

2. DEFINITIONS AND IMPORTANCE OF CAREER DEVELOPMENT

A career can be defined as the pattern or sequence of work roles of an individual. Traditionally, the word applied only to those occupying managerial and professional roles, but increasingly it is seen as appropriate for everyone in relation to their work roles. Also, the word career has been used to imply upward movement and advancement in work roles. As we have noted, many organisations no longer offer a traditional career, or only offer it to a selected few. Enforced redundancies, flatter structures, shortterm contracts, availability of part-time rather than full-time work, all break the idealised image of career. We now recognise other moves as legitimate expressions of career development, including development and extension within the job itself, lateral moves and the development of portfolio work. Career can also be conceptualised more broadly in terms of ‘the individual’s development in learning and work throughout life’ (Collin and Watts 1996), and thus includes voluntary work and other life experiences. Indeed Adamson et al. (1998) go so far as to say that a good curriculum vitae may no longer be one with an impressive list of job titles of increasing seniority, but rather a rich cv (e.g. one which includes a variety of work and non-work activities). (p. 256)

Male careers are becoming increasingly similar to the traditional fragmented pattern of women’s careers (Goffee and Nicholson 1994), and many men are generally keener to develop careers which take account of personal and family needs, including children’s education, partner’s career and quality of life. Career development is no longer a standalone issue and needs to be viewed in the context of the life and development of the whole person and not just the person as employee.

We view career development as something experienced by the individual (sometimes referred to as the internal career), and therefore not necessarily bounded by one organisation. This also means that the responsibility for managing a career is with the individual, although the organisation may play a key facilitating and supporting role.

The primary purpose of career development is to meet the current and future needs of the organisation and the individual at work, and this increasingly means developing employability. On this basis Walton (1999) argues that it is increasingly difficult to disentangle career development from general training and development. We could make a strong case for the value of self-development here. Career success is seen through the eyes of the individual, and can be defined as individual satisfaction with career through meeting personal career goals, while making a contribution to the organisation. Although in this chapter we prioritise the needs of the individual, in Chapter 3 we prioritise the needs of the organisation when we review replacement and succession planning.

We have given priority to the individual in career development, but it is worth noting the general benefits career development provides for the organisation:

- It makes the organisation attractive to potential recruits.

- It enhances the image of the organisation, by demonstrating a recognition of employee needs.

- It is likely to encourage employee commitment and to reduce staff turnover.

- It is likely to encourage motivation and job performance as employees can see some possible movement and progress in their work.

- Perhaps most importantly it exploits the full potential of the workforce.

Before looking at how individuals can manage their career development with organisational support, we need to review some of the concepts underlying the notion of career.

3. UNDERSTANDING CAREERS

3.1. Career development stages

Many authors have attempted to map out the ideal stages of a successful career and in this section we loosely use the five stages outlined by Greenhaus and Callanan (1994). Few careers follow such an idealised pattern, and even historically such a pattern did not apply for all employees. However, the stage approach offers a useful framework for understanding career experiences, if we use it flexibly as a tool for understanding careers rather than as a normative model.

Stage 1: occupational choice: preparation for work

This first stage involves developing an occupational self-image and will of course reappear for those who wish to change career later in life The key theme is a matching process between the strengths/weaknesses, values and desired lifestyle of the individual and the requirements and benefits of a range of occupations. One of the difficulties that can arise at this stage is a lack of individual self-awareness. There are countless tests available to help identify individual interests, but these can only complete part of the picture, and need to be complemented by structured exercises, which help people look at themselves from a range of perspectives. Other problems involve individuals limiting their choice due to social, cultural, gender or racial characteristics. Although we use role models to identify potential occupations, and these extend the range of options we consider, this process may also close them down. Another difficulty at this stage is gaining authentic information about careers which are different from the ones pursued by family and friends.

Stage 2: organisational entry

This stage involves the individual in both finding a job which corresponds with his or her occupational self-image, and starting to do that job. Problems here centre on the accuracy of information that the organisation provides, so that when the individual begins work expectations and reality may be very different. Recruiters understandably ‘sell’ their organisations and the job to potential recruits, emphasising the best parts and neglecting the downside. Applicants often fail to test their assumptions by asking for the specific information they really need. In addition, schools, colleges and universities have, until recently, only prepared students for the technical demands of work, ignoring other skills that they will need, such as communication skills, influencing skills and dealing with organisational politics. To aid organisational entry, Wanous (1992) has suggested the idea of realistic recruitment with the emphasis on providing accurate information, to which we refer in Chapter 8. Pazy and his colleagues (2006) also demonstrate how information-free interventions can be beneficial in this respect. They provided a decisionmaking tool to a random selection of candidates eight months prior to their joining the Technical School of the Israeli air force so that they could use this for occupational choice decisions. The candidates who had been introduced to the tool had significantly lower turnover during the programme and a lower turnover six months after the programme. The authors suggest that the tool enabled the trainees to make better career choices and also made trainees aware of self-determination in their career.

Stage 3: early career – establishment and achievement

The establishment stage involves fitting into the organisation and understanding ‘how things are done around here’. Thorough induction programmes are important, but more especially it is important to provide the new recruit with a ‘real’ job and early challenges rather than a roving commission from department to department with no real purpose, as is often found on trainee schemes. Feedback and support from the immediate manager are also key. This has implications, for example for the design of graduate training programmes.

The achievement part of this stage is demonstrating competence and gaining greater responsibility and authority. It is at this stage that access to opportunities for career development becomes key. Development within the job and opportunities for promotion and broadening moves are all aided if the organisation has a structured approach to career development, involving career ladders, pathways or matrices, but not necessarily hierarchical progression. Feedback remains important, as do opportunities and support for further career exploration and planning. Organisations are likely to provide the most support for ‘high fliers’ who are seen as the senior management of the future and who may be on ‘fast track’ programmes.

Stage 4: mid-career

Mid-career may involve further growth and advancement or the maintenance of a steady state. In either case it is generally accompanied by some form of re-evaluation of career and life direction. A few will experience decline at this stage. For those who continue to advance, organisational support remains important. Some people whose career has reached a plateau will experience feelings of failure. Organisational support in these cases needs to involve the use of lateral career paths, job expansion, development as mentors of others, further training to keep up to date and the use of a flexible reward system.

Stage 5: late career

The organisation’s task in the late career stage is to encourage people to continue performing well. This is particularly important as some sectors are experiencing skills shortages and there are moves by some companies to allow individuals to stay at work after the state retirement age. Demographics indicate that in the UK we have an ageing labour force, and the ‘early retirement’ culture of the 1980s and early 1990s, when many retired at around the ago of 50, has all but disappeared, although subtle pressures to retire early probably remain. In addition there is also a pressure on individuals to work longer to improve their pensions and the 2006 Age Discrimination Act prohibits organisations from retiring anyone under 65 without good reason and provides a statutory right for individuals to request to remain working after the age of 65.

Despite the stereotypes that abound defining older workers as slower and less able to learn, evidence suggests that the over-50s can be valuable employees who perform well if managed appropriately. Greenhaus and Callanan point out that the availability of flexible work patterns, clear performance standards, continued training and the avoidance of discrimination are helpful at this stage, combined with preparation for retirement. Portfolio careers can be a particularly attractive option at this stage. Organisations are sometimes unwilling to invest in the over-50s as, from an economic perspective, there is less time for payback. However as retirement is delayed and protean careers increase ongoing learning is even more important, rather than less. Greller (2006) found no differences between the employed 50-70 age group and other age groups in terms of the hours spent on professional development (work-related-knowledge skills development and the development of career opportunities) and also found that time spent was associated with career motivation (as for other age groups). Interestingly, though, they found that the initiative for most activities for the 50-70 age group came from the people themselves rather than from organisation.

3.2. Career balance

Much of the original work done on describing career stages was carried out by analysing the experiences of those who were both male and white, so the analyses are clearly inadequate for our contemporary world of work and we still lack satisfactory explanations of career development that can embrace the full variety of ethnic backgrounds, gender and occupational variety.

There is considerable evidence that women and those from racial minorities limit their career choices, both consciously and unconsciously, for reasons other than their basic abilities and career motives. Social class identity may have the same impact. Employers need at least to be aware of such forces and ideally would explore such constraints with their employees to encourage individual potential to be exploited to the full.

The acceptance of such idealised career development stages as described above, particularly in an era of work intensification, leaves little room for family and other interference in career development, and until recently there has been no place in career development and even in the thinking about careers for those who do not conform to the stages outlined. There are hopeful signs of increasing recognition that career and life choices need to be explored in unison. There has also been little recognition of the commercial environment and the impact that this has on career development stages for many individuals. Considerable attention is being paid, currently, to the concept of work-life balance where aspects of work are combined with other life choices and Dickmann et al. (2006), for example, note that this is a significant factor in career planning for growing numbers of both female and male managers. However Hirsh (2003) warns that:

If employees want to get on they should seek qualifications and training, greater responsibility and varied work experiences. They should not work reduced hours, take career breaks, work from home or get ill. (p. 7)

We devote Chapter 31 to this issue, and Rabinowitz (2007) provides a useful review of recent books which focus on work, family and life interfaces.

Source: Torrington Derek, Hall Laura, Taylor Stephen (2008), Human Resource Management, Ft Pr; 7th edition.

You actually make it seem so easy along with your presentation but I to find this matter to be actually one thing which I think I might never understand. It sort of feels too complex and very large for me. I am taking a look ahead to your next post, I will attempt to get the hang of it!

Outstanding post, I conceive people should acquire a lot from this weblog its rattling user pleasant.