Before we present in detail the debate over the implications the epistemological positioning of a research project may have on its design, we will briefly mention the evolution of research approaches that has brought about this debate. The related question of the degree of maturity of knowledge in a field of study and the type of design that is appropriate will be the subject of the third part of this section.

1. Research Approaches in the Social Sciences

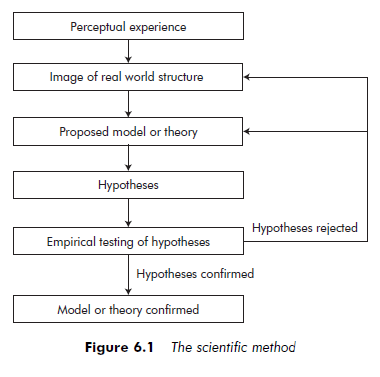

Approaches to research in the social sciences evolved significantly over the course of the twentieth century. Until the 1950s, these were primarily centered on the positivist paradigm of Comte, based on the postulate of the objectivity of reality (see Chapter 1). This concept of research is represented by the scientific method that is today presented in most textbooks (see Figure 6.1). According to this approach:

Scientific investigations begin in the free and unprejudiced observation of facts, proceed by inductive inference to the formulation of universal laws about these facts, and finally arrive by further induction at statements of still wider generality known as theories; both laws and theories are ultimately checked for their truth content by comparing their empirical consequences with all the observed facts, including those with which they began.

(Blaug, 1992: 4)

According to this positivist paradigm, theories are accepted if they correspond to reality – understood through empirical observation – and are rejected if they do not. The test phase is dominated by surveys, followed by statistical analysis (Ackroyd, 1996).

New perspectives developed in the philosophy of science from the early 1950s. Within the positivist paradigm, new perceptions suggested a modification of the status of theories and the scientific method, and the hypothetico- deductive model was adopted. According to this model (Popper, 1977) explained, a theory cannot be confirmed but only corroborated (or temporarily accepted). In terms of method, this new perception meant that hypotheses had to be formulated in such a way as to be refutable, or ‘falsifiable’. It prohibited the development of ad hoc or auxiliary hypotheses, unless they increased the degree to which the system could be refuted. Other paradigms appeared alongside these concepts: in particular, constructivism and the interpretative paradigm. According to these new paradigms, there is not one sole reality – which would be possible to apprehend, however imperfectly – but multiple realities; the product of individual or collective mental constructions that are likely to evolve over the course of time (Guba and Lincoln, 1994).

During this period, along with a lot of activity in philosophy of science, new research approaches were promoted in both the constructivist and the interpretative paradigms. The majority, such as grounded theory in the positivist paradigm and participatory action research in the constructivist paradigm, were qualitative. The increased use of new approaches was coupled with an attempt to formalize both the approaches themselves and the data collection and analysis methods employed. Researchers today have a vast choice of options available through which to approach the question they have chosen to study (Hitt et al., 1998).

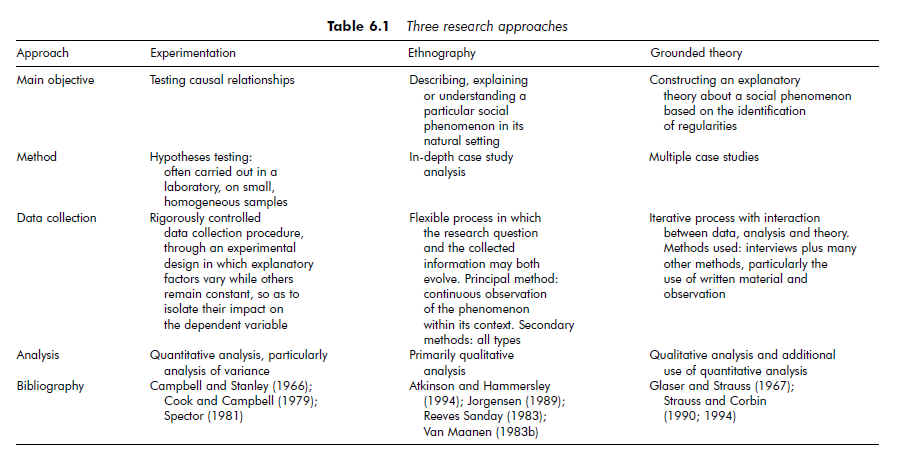

We do not propose to detail all of these many and varied methods and approaches here. Nevertheless, by way of illustration, we will present a simplified version of certain generic research approaches: ethnography, grounded theory and experimentation (see Table 6.1).

2. The Influence of Paradigm on Design

Many writers contend that epistemological positioning will have a decisive influence over the design a researcher will be able to implement. Pure positivism, for example, accepts only the scientific method (based on using quantitative data to test hypotheses) as likely to produce truly scientific knowledge. Constructivists, on the other hand, will maintain that the study of individuals and their institutions requires specific methods that differ from those inherited from the natural sciences. These positions have often led to the two approaches being seen as antithetic – and to qualitative approaches being considered as an alternative to quantitative positivist approaches.

Without going into further detail on the various elements of this debate, we will merely mention here that the relationship between research design and epistemological positioning is by no means simple, and that the association of qualitative methods and constructivism on the one hand and quantitative methods and positivism on the other represents an oversimplification of this relationship.

According to Van Maanen (1983a), although qualitative approaches are more likely to be guided by constructivist logic, that does not preclude them being carried out according to positivistic scientific logic. According to Yin (1990), a case study can be used to test a theory. This qualitative procedure then clearly fits in with the positivist ‘falsification’ approach of Popper.

In more general terms, research approaches are not systematically attached to a particular paradigm. Ethnography, for example, is used by proponents of both paradigms (Atkinson and Hammersley, 1994; Reeves Sanday, 1983). Ethnography may be used by a researcher who wishes to understand a reality through an interpretative process, or by a positivist wishing to describe reality, to discover an explanatory theory, or to test a theory (Reeves Sanday, 1983).

At the level of data collection and analysis, the links between paradigm and methods are even more tenuous. Ackroyd (1996) considers that, once established, methods no longer belong to the discipline or the paradigm in which they were engendered, but rather become procedures whose use is left to the discretion of the researcher. In this respect, the association of qualitative methods and constructivism, and of quantitative methods and positivism, seems outdated. As we saw with research approaches, the choice of qualitative data collection or analysis methods is not the prerogative of one particular paradigm. Similarly, whereas qualitative methods are dominant in the constructivist and interpretative paradigms, quantitative methods are not excluded. They can notably permit additional information to be made available (Atkinson and Hammersley, 1994; Guba and Lincoln, 1994; Morse, 1994). Certain authors go so far as to encourage the simultaneous or sequential use of qualitative and quantitative methods to study a particular question, in accordance with the principle of triangulation (Jick, 1979). When the results obtained by the different methods converge, the methods reinforce each other and concur, increasing the validity of the research.

There is no simple link between a researcher’s epistemological positioning and any particular research approach. The range of designs that can be implemented proves to be even wider than a restricted appreciation of the relation between epistemology and methodology would suggest. It is not just the method in itself, but the way it is applied and the objective it serves that indicate the epistemological positioning of research. However, the overall coherence of the research project is paramount, and choices made in constructing a design should not compromise this coherence. Several writers feel that the researcher’s chosen epistemological position should always be made clear for this reason (Denzin and Lincoln, 1994; Grunow, 1995; Otley and Berry, 1994).

3. ‘Maturity’ of Knowledge

The debate over epistemological positioning and its impact on research design is echoed in a second controversy; over the degree of ‘maturity’ of knowledge in a given field and the type of design that can be used.

If we accept a traditional conception of scientific research, a relationship should indeed exist between these two elements. According to the normative model, the research process should begin with exploratory studies, to be followed by more ‘rigorous’ approaches: experiments and surveys. Exploratory studies are designed to encourage the emergence of theories, and to identify new concepts or new explanatory variables in fields in which knowledge is as yet poorly developed. Hypotheses and models are formulated at this stage, which must then be tested within a ‘stricter’ methodological framework. Exploratory studies use ‘small’ samples, and this presents two significant deficiencies with regard to the requirements of the scientific method. First, the rules of statistical inference prohibit researchers from generalizing from their results: the samples are too small and not sufficiently representative. Moreover, such exploratory studies do not permit researchers to sufficiently isolate the effect of a variable by controlling other potentially influential variables. Therefore, according to this normative model of scientific progress, we can only increase our knowledge by testing hypotheses using ‘rigorous’ research approaches based on quantitative data (Camerer, 1985). This model also implies that it would be inappropriate to carry out experimental or quantitative studies in a relatively unexplored field, since they must be preceded by case studies.

Alongside this research tradition, which is still widely endorsed, are rival models that do not confine qualitative approaches to the proposal of theories and quantitative approaches to the testing of them. According to these models, explanatory theories can emerge from a purely descriptive correlation study of quantitative data, or even from observations made within an experimental design. Case studies can also be used to test existing theories or to increase their scope to include other contexts.

Some researchers question the sequential aspect of the progression of research work: exploring reality before testing hypotheses. According to Schwenk (1982), it is possible to follow two different approaches – case studies and laboratory experiments – concurrently, from the same initial conceptual work; at least for research questions where the influence of the context is not decisive, and therefore where laboratory experimentation is possible.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021