Primary data collection cannot be a discreet step in the research process, particularly in qualitative research, which requires prolonged investigation in the field. This being the case, managing the interaction between the researcher and the data sources is a vital issue. We will conclude this section by presenting several approaches and source management strategies that can be used for collecting primary data.

1. Principal Methods

1.1. Interviewing

Interviewing is a technique aimed at collecting, for later analysis, discursive data that reflects the conscious or unconscious mind-set of individual interviewees. It involves helping subjects to overcome or forget the defense mechanisms they generally use to conceal their behavior or their thoughts from the outside world.

Individual interviews In qualitative research, the interview involves questioning the subject while maintaining an empathetic demeanor: that is, accepting the subject’s frame of reference, whether in terms of feelings or relevance. Subjects can say anything they wish, and all elements of their conversation have a certain value because they refer directly or indirectly to analytical elements of the research question. This is the opposite of following a set series of predetermined questions, designed to aggregate the thoughts or knowledge of a large number of subjects, as is characteristic of interviewing for quantitative research (Stake, 1995).

If such a principle is followed, the degree to which the researcher directs the dynamics of the interview can vary (Rubin and Rubin, 1995). Traditionally, a distinction is drawn between two types of interview: unstructured and semistructured. In an unstructured interview, the interviewer defines a general subject area or theme without intervening to direct the subject’s remarks. He or she limits interventions to those that facilitate the discussion, express understanding, provide reminders based on elements already expressed by the subject, or go more deeply into discursive elements already expressed. In a semi-structured interview, also called a ‘focused’ interview (Merton et al., 1990), the researcher applies the same principles, except that a structured guide allows the researcher to broach a series of subject areas defined in advance. This guide is completed during the course of the interview, with the aid of other questions

‘Main questions’ can be modified if, in the course of the interview, the subject broaches the planned subject areas without being pressed by the interviewer. In some cases certain questions may be abandoned, for example if the subject shows reticence about particular subjects and the researcher wishes to avoid blocking the flow of the face to face encounter. An interview rarely follows a predicted course. Anything may arise during the interview – interviewing demands astuteness and lively interest on the part of the researcher! In practice, a researcher who is absorbed in taking notes risks not paying enough attention to be able to take full advantage of opportunities that emerge in the dynamics of the interview. For this reason it is strongly advised to tape-record the interview, even though this can make the interviewee more reticent or circumspect in his or her remarks. An added advantage is that the taped data will be more exhaustive and more reliable. More detailed analyses can then be carried out on this data, notably content analyses.

Two different interviewing procedures are possible. Researchers can either conduct a systematic and planned series of interviews with different subjects, with an eye to comparing their findings, or they can work heuristically, using information as it emerges to build up their understanding in a particular field. Using the first method, the researcher is rigorous about following the same guide for all of the interviews, which are semi-directed. Using the second method, the researcher aims for a gradual progression in relation to the research question. Researchers might start with interviews that are only slightly structured, with the research question permanently open to debate, which allows subject participation in establishing the direction the research will take. They would then conduct semi-structured interviews on more specific subject areas. The transition from a ‘creative’ interview to an ‘active’ interview can provide an illustration of this procedure (see below).

When research involves several actors within an organization or a sector, they might not have the same attitude to the researcher or the same view of the research question. The researcher may have to adapt to the attitude of each actor. According to Stake (1995), each individual questioned must be seen as having particular personal experiences and specific stories to tell. The way they are interviewed can therefore be adapted in relation to the information they are best able to provide (Rubin, 1994). Researcher flexibility is, therefore, a key factor in the successful collection of data by interview. It may be useful to organize the interviews so they are partly non-directive, which leaves room for suggestions from the subjects, and partly semi-directive, with the researcher specifying what kind of data is required. As Stake (1995: 65) points out; ‘formulating the questions and anticipating probes that evoke good responses is a special art’.

Group interviews A group interview involves bringing different subjects together with one or more animators. Such an interview places the subjects in a situation of interaction. The role of the animator(s) is delicate, as it involves helping the different individuals to express themselves, while directing the group dynamic. Group interviewing demands precise preparation, as the aims of the session and the rules governing the discourse must be clearly defined at the beginning of the interview: who is to speak and when, how subjects can interject and what themes are to be discussed.

Specialists in qualitative research differ on the effectiveness of group interview. Some argue that a group interview enables researchers to explore a research question or identify key information sources (Fontana and Frey, 1994). The interaction between group members stimulates their reflection on the problem put before them (Bouchard, 1976). Others point out that, in group interviews, subjects can become reticent about opening up in front of other participants (Rubin and Rubin, 1995). In management research, the biases and impediments inherent to group interviews are all the more obvious. Care is required when judging the authenticity of the discussion, as power games and the subjects’ ambitions within the organization can influence the flow of the interview. If the inquiry is actually exploring these power games, a group interview will tend to reveal elements that the researcher can then evaluate using other collection methods. A group interview can also be used to obtain confirmation of latent conflicts and tensions within an organization that have already been suggested by other collection methods.

As in individual interviews, the animator of a group interview must be flexible, empathetic and astute. However, running a group interview successfully requires certain specific talents as well, to avoid altering the interview dynamic, which would distort the data collected (see below). For example, according to Merton et al. (1990), the researcher who is running a group interview must:

- prevent any individual or small coalition from dominating the group

- encourage recalcitrant subjects to participate

- obtain from the group as complete an analysis as possible of the subject of the inquiry.

Fontana and Frey (1994) point to another useful talent: knowing how to strike a balance between playing a directive role and acting as a moderator, so as to pay attention both to guiding the interview and to maintaining the group dynamic.

Finally, the group must contain as few superfluous members as possible and should fully represent all actors the research question relates to (Thompson and Demerath, 1952).

Taking into account the points we have just covered, group interviewing, with rare exceptions, cannot be considered a collection technique to be used on its own, and should always be supplemented by another method.

1.2. Observation

Observation is a method of data collection by which the researcher directly observes processes or behaviors in an organization over a specific period of time. With observation, the researcher can analyze factual data about events that have definitely occurred – unlike verbal data, the accuracy of which should be treated with some caution.

Two forms of observation can be distinguished, in relation to the viewpoint the researcher takes towards the subjects being observed (Jorgensen, 1989; Patton, 1980). The researcher may adopt either an internal viewpoint, using an approach based on participant observation, or an external viewpoint, by conducting non-participant observation. Between these two extremes, the researcher can also opt for intermediate solutions. Junker (1960) and Gold (1970) define four possible positions the researcher in the field may adopt: the complete participant, the participant as observer, the observer as participant and the complete observer.

Participant observation When carrying out fieldwork, researchers must choose the degree to which they wish to ‘participate’. We distinguish three degrees of researcher participation.

The researcher can, first, be a ‘complete participant’. In this case, he or she does not reveal his or her role as a researcher to the subjects observed. The observation is thus covert. Complete participation presents both advantages and disadvantages. The data collected is not biased by the reactivity of the subjects (Lee, 1993). According to Douglas (1976), one of the few supporters of ‘covert’ observation via complete participation, this data collection technique is justified by the conflictual nature of social existence, and the resistance that exists vis-a-vis any type of investigation, even scientific. However, in opting for ‘covert’ observation, researchers may find it difficult to dig deeper, or confirm their observations through other techniques, such as interviewing. They also run the crippling risk of being discovered. The ‘complete participant’ is often led to use sophisticated methods of recording data so as to avoid detection (Bouchard, 1976). They have very little control over selection of their data sources, and their position in the field remains fixed: it cannot be modified, which means important opportunities may be missed (Jorgensen, 1989). Finally, ‘covert’ observation poses serious ethical problems (Punch, 1986). It can only be justified in exceptional circumstances, and cannot be defended by simply arguing that one is observing subjects so as to collect ‘real data’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

The researcher can opt for a lesser degree of participation, taking the role of ‘participant as observer’. This position represents a compromise. The researcher has a greater degree of freedom to conduct the investigations, and he or she can supplement his or her observations with interviews. Nevertheless, the researcher exposes himself or herself to subject reactivity, as he or she is appointed from within the organization. The researcher’s very presence will have an impact on subject-sources of primary data, who may become defensive in face of the investigation. Take the case of a salaried employee in an organization who decides to do research work. His status as a member of the organization predominates over his role as researcher. The conflict of roles which arises can make it difficult for the researcher to maintain his or her position as a fieldworker.

Finally, the researcher can be an ‘observer as participant’. His or her participation in the life of the organization being studied remains marginal, and his or her role as a researcher is clearly defined for the subject-sources. At the beginning of the study, the researcher risks encountering resistance from those being observed. However, such resistance can lessen with time, enabling the researcher to improve his or her capacity to conduct the observation. The researcher’s behavior is the determining factor here. If he or she succeeds in gaining the confidence of the subject-sources, he or she then has more latitude to supplement the observation with interviews and to control the selection of data sources. The key is to remain neutral in relation to the subjects.

Non-participant observation There are two types of non-participant observation: casual and formal. Casual observation can be an elementary step in an investigation, with the aim of collecting preliminary data in the field. It can also be considered as a complementary data source. Yin (1989) notes that, during a field visit to conduct an interview, researchers may observe indicators, such as the social climate or the financial decline of the organization, which they could then include in their database. If they decide to supplement verbal data obtained in interviews by systematically collecting observed data (such as details on the interviewee’s attitude and any non-verbal communication that may take place), the observation can then be described as formal. Another way of carrying out formal observation as part of qualitative research can be systematically to observe certain behaviors over specific periods of time.

- 1.3. ‘Unobstrusive’ methods

There is another way of collecting primary data that bisects the classification of collection methods that we have adopted so far. This involves using ‘unobstru- sive’ methods. The primary data collected in this way is not affected by the reactivity of the subjects, as it is gathered without their knowledge (Webb et al., 1966). As demonstrated in Chapter 4, data obtained in this fashion can be used to supplement or confirm data collected ‘obtrusively’.

Webb et al. (1966) proposed a system of classifying the different elements the researcher can use to collect data ‘unobtrusively’ into five categories:

- Physical traces: such as the type of floor covering used (generally more hard-wearing when the premises are very busy), or the degree to which shared or individual equipment is used.

- Primary archives used (running records): includes actuarial records, political and judicial records, other bureaucratic records, mass media.

- Secondary archives, such as episodic and private records: these can include sales records, industrial and institutional records, written documents.

- Simple observations about exterior physical signs: such as expressive movements, physical location, use of language, time duration.

- Behavior recorded through various media: includes photography, audiotape, video-tape.

2. Coordinating Data Sources

One of the major difficulties facing a researcher who wants to conduct qualitative management research lies in gaining access to organizations and, in particular, to people to observe or interview. Researchers need to show flexibility when interacting with the subject-sources of primary data. As the sources are reactive, researchers can run the risk of contaminating them.

2.1. Accessing sources of primary data

Authorized access It is crucial for researchers to establish beforehand whether they need to obtain authorized access to the site they wish to study. Such authorization is not given systematically. Many organizations, either to foster a reciprocal relationship with the research community, or simply by giving in to the mutual curiosity that exists between researchers and potential subjects, do allow access to their employees and sites (offices, production plants, etc.). Other organizations cultivate a culture of secrecy and are more inclined to oppose investigation by researchers. That said, should one refrain from working on a particular site because the company does not allow access? If this were the case, many research projects would never have seen the light of day. A great deal of information can be accessed today without the permission of those it concerns. It is also possible, if need be, to conduct interviews without the express agreement of the company involved. It is, however, more prudent to make the most of opportunities to access organizations that welcome researchers. By adopting this standpoint you can avoid having to confront conflict situations which, even if they do not call the actual research project into question, are nevertheless costly, as they demand extra effort on the part of the researcher. It is therefore useful to gain access to primary data-sources.

Building up trust Negotiating access to a site requires time, patience, and sensitivity to the rhythms and norms of a group (Marshall and Rossman, 1989). Taking things gradually can minimize the potential threat the researcher may represent, and avoid access to the site being blocked (Lee, 1993). Researchers can use collection methods such as participant observation and in-depth interviewing to familiarize themselves with the context in which they are working and avoid, or at least delay, making any potentially damaging faux pas. These methods provide an opportunity to build the kind of trust that is the key to accessing data. While a subject’s trust in a researcher does not guarantee the quality of the data collected, an absence of trust can prejudice the data significantly (Lincoln and Guba, 1985). To win the trust of the data sources, the researcher may need to obtain the sponsorship of an actor in the field. The sponsorship technique saves considerable time. Lee (1993) discusses the most well-known and best example of this technique: Doc, the leader of the Norton gang studied by Whyte (1944) in Street Corner Society. It is, in fact, thanks to Doc that Whyte, whose first attempts to enter the Street Corner Society were a failure, was finally able to gain access. This example illustrates the fundamental nature of a sponsor: he or she must have the authority to secure the other subjects’ acceptance of the researcher.

While having the backing of someone in the field is sometimes very useful, it can nevertheless lead to serious disadvantages in data collection. There are three different roles that sponsors may adopt (Lee, 1993). They can serve as a ‘bridge’ to an unfamiliar environment. They can also serve as a ‘guide’, suggesting directions and, above all, alerting the researcher to any possible faux pas in relation to the subjects. Finally, they can be a sort of ‘patron’ who helps the researcher to win the trust of the other subjects by exerting a degree of control over the research process. Access to the field is obtained indirectly via the ‘bridge’ and the ‘guide’ and, directly, via the ‘patron’. Lee (1993) highlights the other side of the coin in relation to access with the help of a sponsor. In bringing the researcher onto the site, or sites, being studied, patrons exert an influence inherent to their reputation, with all the bias this entails. Moreover, according to our own observations, the sponsor as ‘patron’ can limit the study through the control he or she exercises over the research process. Sponsors can become adversaries if the process takes what they consider to be a threatening turn. Researchers must therefore take care not to turn systematically to the same sponsor, or they run the risk of introducing a ‘heavy’ instrumental bias. Subjects will unavoidably be selected through the prism of the sponsor’s perception, rather than according to theoretical principles. To avoid this type of phenomenon, researchers should take advantage of their familiarity with the terrain and seek the patronage of other actors.

Flexibility Always indispensable when using secondary data (for example, in relation to data availability), researcher flexibility (or opportunism) becomes even more necessary when managing primary data sources. It is pointless to envisage a research project without taking into account the interaction between the researcher and the sources of primary data. The researcher is confronted by the element of the unknown as ‘what will be learned at a site is always dependent on the interaction between investigator and context’ and ‘the nature of mutual shapings cannot be known until they are witnessed’ (Lincoln and Guba, 1985: 208).

2.2. Source contamination

One of the critical problems in managing primary data lies in the various contamination phenomena researchers have to confront. While they need not operate in a completely neutral fashion, they must both be conscious of and carefully manage the contamination risks engendered by their relationships with their sources.

Three types of contamination can occur: intra-group contamination, contamination between the researcher and the population interviewed, and contamination between primary and secondary data sources. We can define contamination as any influence exerted by one actor upon another, whether this influence is direct (persuasion, seduction, the impression one makes, humor, attitude, behavior, etc.) or indirect (sending a message via a third party, sending unmonitored signals to other actors, circulation of a document influencing the study sample, the choice of terms used in an interview guide, etc.).

Intra-group contamination is born of the interaction between the actors interviewed. When a researcher is conducting a long-term investigation on a site, those involved talk among themselves, discussing the researcher’s intentions and assessing what motivates his or her investigations. If a sponsor introduced the researcher, the actors will tend to consider the sponsor’s motivation and that of the researcher as one and the same. The researcher can appear to be a ‘pioneering researcher’ guided by the sponsor. The subject-sources of primary data will tend to contaminate each other when exchanging mistaken ideas about the researcher’s role. The effect is that a collective attitude is generated towards the researcher, which can heavily influence the responses of the interviewees. When a researcher is working on a sensitive site, the collective interests associated to the site’s sensitivity tends to increase intra-group contamination (Mitchell, 1993). The sponsor’s role as a mediator and conciliator becomes essential in ensuring that the researcher continues to be accepted. However, while well intentioned, sponsors – if not sufficiently briefed by the researcher – can do more harm than good by giving the group a biased picture of the research objectives so as to make their ‘protege’ better accepted.

The sponsor can also contaminate the researcher. This happens quite often, as the sponsor, in providing access to the actors will, at the same time, ‘mold’ the interviewee population and the sequence of the interviews. This first type of influence can be benign as long as the sponsor does not take it upon himself or herself to give the researcher his or her personal opinion about – or evaluation of – ‘the actor’s real role in the organization’. It is very important that researchers plan exactly how they are going to manage their relationship with the sponsor, as much in the sense of limiting this key actor’s influence on the research process, as in relation to ensuring that those being studied do not lose their confidence in the research and the researcher.

Finally, secondary sources can be both contaminated and contaminating at the same time. Where internal documents are concerned, researchers must take care they have clearly identified the suppliers and authors of the secondary sources used. Actors may influence, or may have influenced, these sources. For example, actors have a tendency to create firewalls and other barriers when archiving or recording internal data so as to hide their errors by accentuating the areas of uncertainty in the archives. In large industrial groups, these firewalls are constructed using double archiving systems that separate Head Office archives from those labeled ‘General Records’ or ‘Historical Records’. This works as a filtering mechanism to shield the motivations behind, or the real conditions surrounding, the organization’s decisions. This is all the more true in a period of crisis, when urgent measures are taken to deal with archives (the destruction of key documents, versions purged before being archived). In such a case the data available to researchers will hamper their work, as it portrays a situation as has been ‘designed’ by the actors involved.

While one cannot circumvent this problem of contamination, one solution lies in the researcher systematically confronting actors with any possibilities of contamination discovered during the course of the research. Researchers can resort to double-sourcing, that is, confirming information supplied by one source with a second source. They can make the actors aware of the possibility of contamination, asking for their help to ‘interpret’ the available secondary sources. Another solution lies in replenishing one’s sources, and removing those sources that are too contaminated. This demands a heavy sacrifice on the part of the researcher, who must discard as unusable any data that is likely to be contaminated. Such an approach nevertheless enables researchers to guarantee the validity of their results.

3. Strategies for Approaching and Managing Data Sources

We present several strategies for approaching and managing data sources. We describe the options open to researchers depending on their research question, the context of their data collection and their personal affinities.

3.1. Contractual and oblative approaches

To avoid misunderstanding, and as protection if any disputes arise, one can consider bringing the research work within the terms of a contract. This can reassure the organization that the researcher’s presence on their premises will be for a limited time period. Indeed, access to all of an organization’s data sources, both primary and secondary, can be conditional to the existence of such a contract. The contract generally relates to the researcher’s obligation to provide the organization in question with a report of the research. To protect their own interests, researchers should be as honest and precise as possible about the purpose of their research.

A contractual framework can influence the research work. The contract should clearly specify which data collection methods are to be employed, as such precision can be very useful if any disputes arise. Although researchers may at times seek funding from an organization to finance their work, if they wish to have a significant degree of freedom, they should avoid placing themselves in a subordinate position. It could be in the researcher’s interest to place reasonable limits on any contractual responsibility. The most crucial part of a research contract with an organization concerns the confidentiality of the results and publication rights. It is legitimate for an organization to protect the confidentiality of its skills, designs, methods, codes, procedures and documents. While it is useful to submit one’s work to the organization before final publication, the researcher must not become a ‘hostage’ to the organization’s wishes. In fact, a researcher can set a deadline for the organization to state any disagreement, after which authorization to publish is considered to have been given. Finally, it is worthwhile remembering that researchers retain intellectual property rights over their work, without any geographic or time limit. Negotiations over intellectual property rights can very quickly become difficult, particularly if the research concerns the development of management instruments.

In contrast to this contractual arrangement, the researcher can take a much more informal approach, which we will describe as oblative, as it is based on a spirit of giving. While it may well seem anachronistic to refer to a gift in management research, this kind of approach can turn out to be highly productive in terms of obtaining rare and relevant data. If the researcher is keen for the subjects to participate in crafting the research question, and establishes an interpersonal relationship that is specific to each case and is based on mutual trust, patiently built up, subjects can become the source of invaluable data. An oblative approach is founded on trust and keeping one’s word. The choice of an oblative approach can be justified if the researcher wishes to maintain a large degree of flexibility in his or her relationship with the primary data sources.

3.2. Covert or overt approaches

In approaching data sources, researchers face the following dilemma: should they employ a ‘covert’ approach – retaining absolute control over the management of the primary data sources and conducting an investigation in which they hide their research aims – or should they opt for an ‘overt’ approach – in which they do not hide their objectives from the subject-sources, but offer them greater control over the investigation process. Each of these options presents advantages and disadvantages.

The choice of a ‘covert’ investigation greatly limits a researcher’s movements in the field, as actors may harbor suspicions about the researcher’s intentions (Lee, 1993). Also, because it leaves the subject no latitude, this type of data- source management raises difficulties regarding the morality of the underlying method (Whyte, 1944). The researcher cannot assume ‘the right to deceive, exploit, or manipulate people’ (Warwick, 1982: 55).

The choice of an ‘overt’ approach, whereby researchers do not hide their research aims, means they have to confront the phenomenon of subject reactivity. ‘If the researcher must expose all his intentions in order to gain access, the study will be hampered’ (Marshall and Rossman, 1989: 56). The researcher also runs the risk of being refused access to the site. An ‘overt’ approach must be parsimonious, and take account of the specificity of the interaction with each subject, the maturity of the researcher-subject relationship, and its limits. Choosing such an approach involves going beyond the strictly technical and calling upon qualities such as ’empathy, sensitivity, humor and sincerity’, which ‘are important tools for the research’ (Rubin and Rubin, 1995: 12).

All told, we consider that, if data is to be collected ‘overtly’, that is with the subjects’ knowledge, managing primary data-sources involves a certain transparency. The ‘covert’ approach, though, seems to us only to be compatible with more discreet collection techniques: collection without the subjects’ knowledge. Such an approach needs to be justified from an ethical point of view: by the fact that the reactivity of the subjects would constitute an instrumental bias, and by the innocuous nature of the research results as far as the subjects are concerned.

3.3. Distance or intimacy in relation to the data source

Should one develop an intimate relationship, or should a certain distance be maintained in relation to the subjects? It is necessary, in this respect, to take account of the ‘paradox of intimacy’ (Mitchell, 1993). The more the researcher develops ‘intimacy’ with those being questioned, the more the interviewees will tend to reveal themselves and disclose information. However, such an attitude on the part of the researcher can have an extremely negative impact on the research in terms of internal validity. The more a researcher becomes involved in ‘dis-inhibiting’ a research subject-source, the more he or she will tend to enter into agreement with the actor, offering a reciprocal degree of intimacy. As Mitchell has pointed out, the researcher also exposes himself or herself to the possibility that the subjects will ‘turn against him or her’ when his or her work is published. After publishing a study of mountain-climbers, Mitchell (1983) was accused of having ‘spied’ on them to obtain his information, when the data had, in fact, become available because the author developed strong intimacy with certain subject-sources. Intimacy with sources can pose very serious problems of loyalty in the relationship after the research work has been completed.

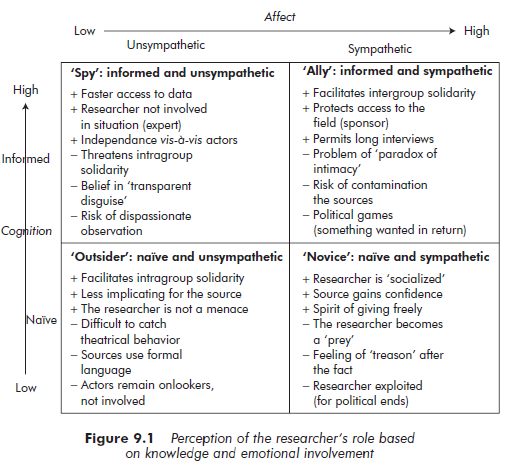

Managing the dilemma of distance versus intimacy also poses problems relating to the amount of information the researcher acquires in the field and the emotional involvement developed with the actors concerned. Mitchell suggests two key aspects that should be considered when looking at the researcher’s role: the knowledge researchers acquire about the site, and their emotional involvement with the subjects (see Figure 9.1.).

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

This is a topic which is near to my heart… Many thanks! Exactly where are your contact details though?