Some may object that the advice I have given so far may work for a specialist, but that a young person who is about to begin his thesis, and who lacks specialized expertise, may encounter many difficulties:

- He may not have access to a well-equipped library, perhaps because he lives in a small city.

- He may have only vague ideas of what he is looking for, and he may not know how to begin searching the subject catalog because he has not received sufficient instructions from his professor.

- He may not be able to travel from library to library. (Perhaps he lacks the funds, the time, or he may be ill, etc.)

Let us then try to imagine the extreme situation of a working Italian student who has attended the university very little during his first three years of study. He has had sporadic contact with only one professor, let us suppose, a professor of aesthetics or of history of Italian literature. Having started his thesis late, he has only the last academic year at his disposal. Around September he managed to approach the professor or one of the professor’s assistants, but in Italy final exams take place during this period, so the discussion was very brief. The professor told him, “Why don’t you write a thesis on the concept of metaphor used by Italian baroque treatise authors?” Afterward, the student returned to his home in a town of a thousand inhabitants, a town without a public library. The closest city (of 90,000 inhabitants) is half an hour away, and it is home to a library that is open daily. With two half-day leaves from work, the student will travel to the library and begin to formulate his thesis, and perhaps do all the work using only the resources that he finds there. He cannot afford expensive books, and the library is not able to request microfilms from elsewhere. At best, the student will be able to travel to the university (with its better-furnished libraries) two or three times between January and April. But for the moment, he must do the best he can locally. If it is truly necessary, the student can purchase a few recent books in paperback, but he can only afford to spend about 20 dollars on these.

Now that we have imagined this hypothetical picture, I will try to put myself in this student’s shoes. In fact, I am writing these very lines in a small town in southern Monfer- rato, 14.5 miles away from Alessandria, a city with 90,000 inhabitants, a public library, an art gallery, and a museum. The closest university is one hour away in Genoa, and in an hour and a half I can travel to Turin or Pavia, and in three to Bologna. This location already puts me in a privileged situation, but for this experiment I will not take advantage of the university libraries. I will work only in Alessandria.

I will accept the precise challenge posed to our hypothetical student by his hypothetical professor, and research the concept of metaphor in Italian baroque treatise writing. As I have never specifically studied this topic, I am adequately unprepared. However, I am not a complete virgin on this topic, because I do have experience with aesthetics and rhetoric. For example, I am aware of recent Italian publications on the baroque period by Giovanni Getto, Luciano Anceschi,

and Ezio Raimondi. I also know of II cannocchiale aristotelico (The Aristotelian telescope) by Emanuele Tesauro, a seventeenth-century treatise that discusses these concepts extensively. But at a minimum our student should have similar knowledge. By the end of the third year he will have completed some relevant courses and, if he had some previous contact with the aforementioned professor, he will have read some of the professor’s work in which these sources are mentioned. In any case, to make the experiment more rigorous, I will presume to know nothing of what I know. I will limit myself to my high school knowledge: I know that the baroque has something to do with seventeenth-century art and literature, and that the metaphor is a rhetorical figure. That’s all.

I choose to dedicate three afternoons to the preliminary research, from three to six p.m. I have a total of nine hours at my disposal. In nine hours I cannot read many books, but I can carry out a preliminary bibliographical investigation. In these nine hours, I will complete all the work that is documented in the following pages. I do not intend to offer this experiment as a model of a complete and satisfactory work, but rather to illustrate the introductory research I will need to complete my final thesis.

As I have outlined in section 3.2.1, upon entering the library I have three paths before me:

- I can examine the subject catalog. I can look for the following entries: “Italian (literature),” “(Italian) literature,” “aesthetics,” “seventeenth century,” “baroque period,” “metaphor,” “rhetoric,” “treatise writers,” and “poetics.”4 The library has two catalogs, one old and one updated, both divided by subject and author. They have not yet been merged, so I must search both. Here I might make an imprudent calculation: if I am looking for a nineteenth-century work, I might assume that it resides in the old catalog. This is a mistake. If the library purchased the work a year ago from an antique shop, it will be in the new catalog. The only certainty is that any book published in the last ten years will be in the new catalog.

- I can search the reference section for encyclopedias and histories of literature. In histories of literature (or aesthetics) I must look for the chapter on the seventeenth century or on the baroque period. I can search encyclopedias for “seventeenth century,” “baroque period,” “metaphor,” “poetics,” “aesthetics,” etc., as I would in the subject catalog.

- I can interrogate the librarian. I discard this possibility immediately both because it is the easiest and because it would compromise the integrity of this experiment. I do in fact know the librarian, and when I tell him what I am doing, he barrages me with a series of titles of bibliographical indexes available to him, even some in German and English. Were I not engaged in this experiment, I would immediately explore these possibilities. However, I do not take his advice into consideration. The librarian also offers me special borrowing privileges for a large number of books, but I refuse with courtesy, and from now on speak only with the assistants, attempting to adhere to the allotted time and challenges faced by my hypothetical student.

I decide to start from the subject catalog. Unfortunately, I am immediately exceptionally lucky, and this threatens the integrity of the experiment. Under the entry “metaphor” I find Giuseppe Conte, La metafora barocca. Saggio sulle poetiche del Seicento (The baroque metaphor: Essay on seventeenth-century poetics) (Milan: Mursia, 1972). This book is essentially my thesis realized. If I were dishonest, I would simply copy it, but this would be foolish because my (hypothetical) advisor probably also knows this book. This book will make it difficult to write a truly original thesis, because I am wasting my time if I fail to say something new and different. But if I want to write an honest literature review, this book could provide a straightforward starting point.

The book is defective in that it does not have a comprehensive bibliography, but it has a thick section of notes at the end of each chapter, including not only references but also descriptions and reviews of the sources. From it I find references to roughly 50 titles, even after omitting works of contemporary aesthetics and semiotics that do not strictly relate to my topic. (However, the sources I have omitted may illuminate relationships between my topic and current issues. As we shall see later, I could use them to imagine a slightly different thesis that involves the relationships between the baroque and contemporary aesthetics.) These 50 titles, all of which are specifically on the baroque, could provide a preliminary set of index cards that I could use later to explore the author catalog. However, I decide to forgo this line of research. The stroke of luck is too singular, and may jeopardize the integrity of my experiment. Therefore, I proceed as if the library did not own Conte’s book.

To work more methodically, I decide to take the second path mentioned above. I enter the reference room and begin to explore the reference texts, specifically the Enciclopedia Treccani (Treccani encyclopedia). Although this encyclopedia contains an entry for “Baroque Art” that is entirely devoted to the figurative arts, there is no entry for “Baroque.” The reason for this absence becomes clear when I notice that the “B” volume was published in 1930: the reassessment of the baroque had not yet commenced. I then think to search for “Secentismo,” a term used to describe the elaborate style characteristic of seventeenth-century European literature. For a long time, this term had a certain negative connotation, but it could have inspired the encyclopedia listing in 1930, during a period largely influenced by the philosopher Benedetto Croce’s diffidence toward the baroque period.

And here I receive a welcome surprise: a thorough, extensive, and mindful entry that documents all the questions of the period, from the Italian baroque theorists and poets such as Giambattista Marino and Emanuele Tesauro to the examples of the baroque style in other countries (B. Gracian, J. Lyly, L. de Gongora, R. Crashaw, etc.), complete with excellent quotes and a juicy bibliography. I look at the date of publication, which is 1936; I look at the author’s name and discover that it is Mario Praz, the best specialist during that period (and, for many subjects, he is still the best). Even if our hypothetical student is unaware of Praz’s greatness and unique critical subtlety, he will nonetheless realize that the entry is stimulating, and he will decide to index it more thoroughly later. For now, I proceed to the bibliography and notice that this Praz, who has written such an excellent entry, has also written two books on the topic: Secentismo e mari- nismo in Inghilterra (Secentismo and Marinism in England) in 1925, and Studi sul concettismo (Studies in Seventeenth- Century Imagery) in 1934. I decide to index these two books. I then find some Italian titles by Benedetto Croce and Alessandro D’Ancona that I note. I find a reference to T. S. Eliot, and finally I run into a number of works in English and German. I note them all, even if I (in the role of our hypothetical student) assume ignorance of the foreign languages. I then realize that Praz was talking about Secentismo in general, whereas I am looking for sources centered more specifically on the Italian application of the style. Evidently I will have to keep an eye on the foreign versions as background material, but perhaps this is not the best place to begin.

I return to the Treccani for the entries “Poetics,” “Rhetoric,” and “Aesthetics.” The first term yields nothing; it simply cross-refers to “Rhetoric,” “Aesthetics,” and “Philology.” “Rhetoric” is treated with some breadth. There is a paragraph on the seventeenth century worthy of investigation, but there are no specific bibliographical directions. The philosopher Guido Calogero wrote the entry on “Aesthetics,” but he understood it as an eminently philosophical discipline, as was common in the 1930s. There is the philosopher Giambattista Vico (1668-1744), but there are no baroque treatise writers. This helps me envisage an avenue to follow: perhaps I will find Italian material more easily in sections on literary criticism and the history of literature than in sections that deal with the history of philosophy. (As I will see later, this is only true until recently.) Nevertheless, under Calogero’s entry “Aesthetics,” I find a series of classic histories of aesthetics that could tell me something: R. Zim- mermann (1858), M. Schlasler (1872), B. Bosanquet (1895), and also G. Saintsbury (1900-1904), M. Menendez y Pelayo (1890-1901), W. Knight (1895-1898), and finally B. Croce (1928). They are almost all in German and English, and very old. I should also say immediately that none of the texts I have mentioned are available in the library of Alessandria, except Croce. I note them anyway, because sooner or later I may want to locate them, depending on the direction that my research takes.

I look for the Grande dizionario enciclopedico UTET (UTET great encyclopedic dictionary) because I remember that it contains extensive and updated entries on “Poetics” and various other sources that I need, but apparently the library doesn’t own it. So I begin paging through the Enciclopedia filosofica (Encyclopedia of philosophy) published by San- soni. I find two interesting entries: one for “Metaphor” and another for “Baroque.” The former does not provide any useful bibliographical direction, but it tells me that everything begins with Aristotle’s theory of the metaphor (and only later will I realize the importance of this information). The latter provides citations of nineteenth- and twentieth-century critics (B. Croce, L. Venturi, G. Getto, J. Rousset, L. Anceschi, E. Raimondi) that I prudently note, and that I will later reencounter in more specialized reference works; in fact I will later discover that this source cites a fairly important study by Italian literature scholar Rocco Montano that was absent from other sources, in most cases because these sources preceded it.

At this point, I think that it might be more productive to tackle a reference work that is both more specialized and more recent, so I look for the Storia della letteratura italiana (History of Italian literature), edited by the literary critics Emilio Cecchi and Natalino Sapegno and published by Gar- zanti. In addition to chapters by various authors on poetry, prose, theater, and travel writing, I find Franco Croce’s chapter “Critica e trattatistica del Barocco” (Baroque criticism and treatise writing), about 50 pages long. (Do not confuse this author with Benedetto Croce whom I have mentioned above.) I limit myself to reading this particular chapter, and in fact I only skim it. (Remember that I am not yet closely reading texts; I am only assembling a bibliography.) I learn that the seventeenth-century critical discussion on the baroque begins with Alessandro Tassoni (on Petrarch), continues with a series of authors (Tommaso Stigliani, Scipione Errico, Angelico Aprosio, Girolamo Aleandro, Nicola Vil- lani, and others) who discuss Marino’s illustrious epic poem Adone (Adonis), and passes through the treatise writers that Franco Croce calls “moderate baroque” (Matteo Peregrini, Pietro Sforza Pallavicino) and through Tesauro’s canonical text II cannocchiale aristotelico which is the foremost treatise in defense of baroque ingenuity and wit and, according to Franco Croce, “possibly the most exemplary of all baroque manuals in all of Europe.”5 Finally, the discussion finishes with the late seventeenth-century critics (Francesco Fulvio Frugoni, Giacomo Lubrano, Marco Boschini, Carlo Cesare Malvasia, Giovan Pietro Bellori, and others).

Here I realize that my interests must center on the treatise writers Sforza Pallavicino, Peregrini, and Tesauro, and I proceed to the chapter’s bibliography, which includes approximately one hundred titles. It is organized by subject, and it is not in alphabetical order. My system of index cards will prove effective in putting things in order. As I’ve noted, Franco Croce deals with various critics, from Tassoni to Frugoni, and in the end it would be advantageous to index all the references he mentions. For the central argument of my thesis, I may only need the works on the moderate critics and on Tesauro, but for the introduction or the notes it may be useful to refer to other discussions that took place during the same period. Ideally, once our hypothetical student has completed the initial bibliography, he will discuss it with his advisor at least once. The advisor should know the subject well, so he will be able to efficiently determine which sources the student should read and which others he should ignore. If the student keeps his index cards in order, he and his advisor should be able to go through them in about an hour. In any case, let us assume that this process has taken place for my experiment, and that I have decided to limit myself to the general works on the baroque and to the specific bibliography on the treatise writers.

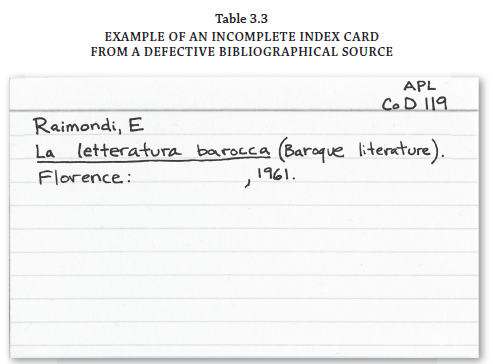

We have already explained how to index books when a bibliographical source is missing information. On the index card for E. Raimondi reproduced below, I left space to write the author’s first name (Ernesto? Epaminonda? Evaristo? Elio?), as well as the publisher’s name (Sansoni? Nuova Italia? Nerbini?). After the date, I left additional space for other information. I obviously added the initialism “APL” that I created for Alessandria Public Library after I checked for the book in Alessandria’s author catalog, and I also found the call number of Ezio (!!) Raimondi’s book: “Co D 119.”

If I were truly writing my thesis, I would proceed the same way for all the other books. But for the sake of this experiment, I will instead proceed more quickly in the following pages, citing only authors and titles without adding other information.

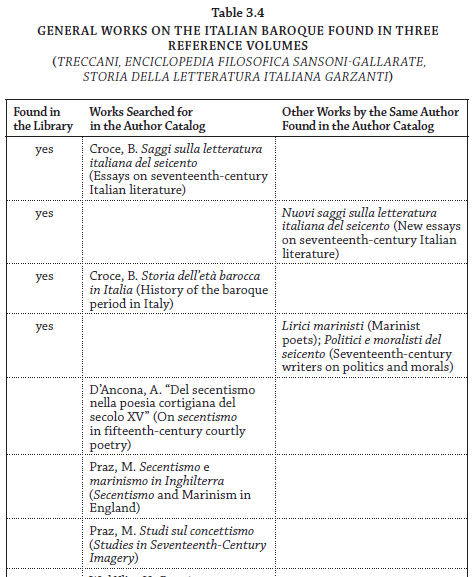

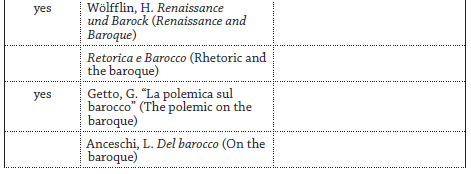

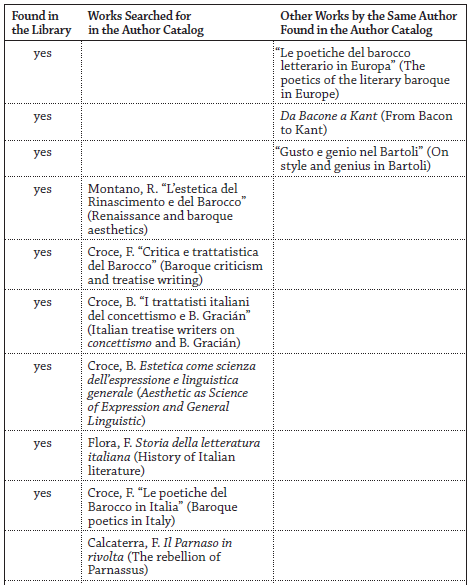

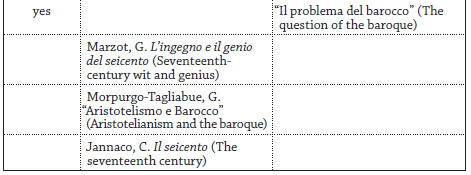

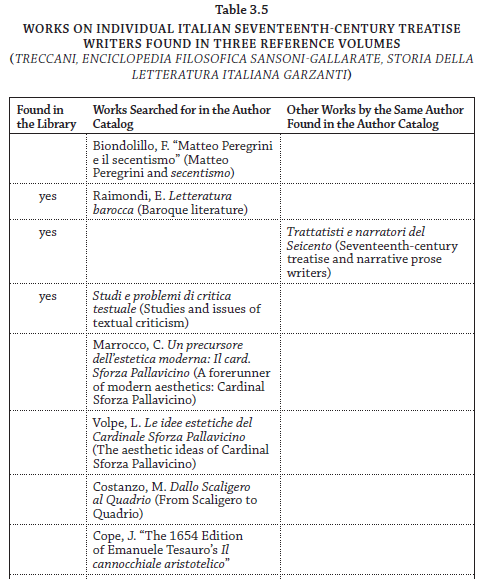

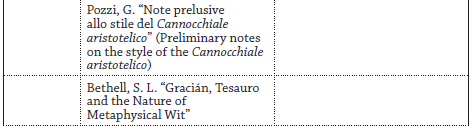

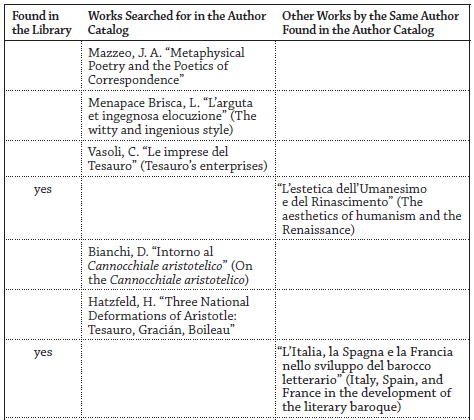

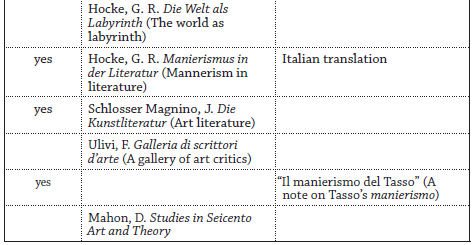

To summarize my work up to this point, I consulted Franco Croce’s essay and the entries in the Treccani and the Enciclopedia filosofica, and I decided to note only the works on Italian treatises. In tables 3.4 and 3.5 you will find the list of what I noted. Let me repeat that, while I made only succinct bibliographical entries for the purpose of this experiment, the student should ideally create an index card (complete with space allotted for missing information) that corresponds with each entry. Also, in each entry in tables 3.4 and 3.5, I have noted a “yes” before titles that exist in the author catalog of the Alessandria library. In fact, as I finished filing these first sources, I took a break and skimmed the library’s card catalog. I found many of the books in my bibliography, and I can consult them for the missing information on my index cards. As you will notice, I found 14 of the 38 works I cataloged, plus 11 additional works that I encountered by the authors I was researching.

Because I am limiting myself to titles referring to Italian treatise writers, I neglect, for example, Panofsky’s Idea: A Concept in Art Theory, a text that, as I will discover later from other sources, is equally important for the theoretical problem in which I am interested. As we will see, when I consult Franco Croce’s essay “Le poetiche del Barocco in Italia” (Baroque poetics in Italy) in the miscellaneous volume Momenti e problemi di storia dell’estetica (Moments and issues in the history of aesthetics), I will discover in that same volume an essay by literary critic Luciano Anceschi on the poetics of the European baroque, one that is three times as long. Franco Croce did not cite this essay in his chapter on the baroque, because he was limiting his study to Italian literature. This is an example of how, by discovering a text through a citation, a student can then find other citations in that text, and so on, potentially infinitely. You see that, even starting from a good history of Italian literature, I am making significant progress.

I will now glance at the Storia della letteratura italiana (History of Italian literature) written by the good old Italian literary critic Francesco Flora. He is not an author who lingers on theoretical problems. Instead, he enjoys savoring the wittiness and originality of particular passages in the texts he analyzes. In fact his book contains a chapter full of amusing quotes from Tesauro, and many other well-chosen quotes on the metaphoric techniques of seventeenth-century authors. As for the bibliography, I am not expecting much from a general work that stops at 1940, but it does confirm some of the classical texts I have already cited. The name of Eugenio D’Ors strikes me. I will have to look for him. On the subject of Tesauro, I find the names of critics C. Trabalza, T. Vallauri, E. Dervieux, and L. Vigliani, and I make a note of them.

Now I move on to consult the abovementioned miscellaneous volume Momenti e problemi di storia dell’estetica. When I find it, I notice that Marzorati is the publisher (Franco Croce told me only that it was published in Milan), so I supplement the index card. Here I find Franco Croce’s essay on the poetics of Italian baroque literature (“Le poetiche del Barocco in Italia”). It is similar to his “Critica e trattatistica del Barocco” that I have already seen, but it was written earlier, so the bibliography is more dated. Yet the approach is more theoretical, and I find the essay very useful. Additionally, the theme is not limited to the treatise writers, as in the previous essay, but deals with literary poetics in general. So, for example, “Le poetiche del Barocco in Italia” treats the Italian poet Gabriello Chiabrera at some length. And on the subject of Chiabrera, the name of literary critic Giovanni Getto (a name I have already noted) comes up again.

In the Marzorati volume, together with Franco Croce’s essay I find Anceschi’s essay “Le poetiche del barocco let- terario in Europa” (The poetics of the literary baroque in Europe), an essay that is almost a book in itself. I realize it is quite an important study not only because it philosophically contextualizes the notion of the baroque and all of its meanings, but also because it explains the dimensions of the question in European culture, including Spain, England, France, and Germany. I again find names that were only mentioned in Mario Praz’s entry in the Enciclopedia Treccani. I also find other names, from Bacon to Lyly and Sidney, Gracian, Gon- gora, Opitz, the theories of wit, agudeza, and ingegno. My thesis may not deal directly with the European baroque, but these notions must serve as context. In any case, if my bibliography is to be complete, it should reflect the baroque as a whole.

Anceschi’s extensive essay provides references to approximately 250 titles. The bibliography at the end is divided into a concise section of general studies and a longer section of more specialized studies arranged by year from 1946 to 1958. The former section highlights the importance of the Getto and Helmut Hatzfeld studies, and of the volume Retorica e Barocco (Rhetoric and the baroque)—and here I learn that it is edited by Enrico Castelli—whereas Anceschi’s essay had already brought my attention to the critical works of Heinrich Wolfflin, Benedetto Croce, and Eugenio D’Ors. The latter section presents a flood of titles, only a few of which, I wish to make clear, I attempt to locate in the author catalog, because this would have required more time than my allotted limit of three afternoons. In any case, I learn of some foreign authors who treated the question from many points of view, and for whom I will nevertheless have to search: Ernst Robert Curtius, Rene Wellek, Arnold Hauser, and Victor Lucien Tapie. I also find references to the work of Gustav Rene Hocke, and to Eugenio Battisti’s Rinascimento e Barocco (The Renaissance and the baroque), a work that deals with the links between the literary metaphor and the poetics of art. I find more references to Morpurgo-Tagliabue that confirm his importance to my topic, and I realize that I should also see Galvano Della Volpe’s work on the Renaissance commentators on Aristotelian poetics, Poetica del Cinquecento (Sixteenth-century poetics).

This realization also convinces me to look at Cesare Vaso- li’s extensive essay (in the Marzorati volume that I am still holding) “L’estetica dell’Umanesimo e del Rinascimento” (The aesthetics of humanism and the Renaissance). I have already seen Vasoli’s name in Franco Croce’s bibliography. In the encyclopedia entries on metaphor that I have examined, I have already noticed (and noted on the appropriate index card) that the question of metaphor had already arisen in Aristotle’s Poetics and Rhetoric. Now I learn from Vasoli that during the sixteenth century there was an entire scene of commentators on Aristotle’s Poetics and Rhetoric. I also learn that between these commentators and the baroque treatise writers there are the theorists of Manierismo who discussed the question of ingenuity as it relates to the concept of metaphor. I also notice the recurrence of similar citations, and of names like Julius von Schlosser. And before leaving Ance- schi, I decide to consult his other works on the topic. I record references to Da Bacone a Kant (From Bacon to Kant), L’idea del Barocco (The idea of baroque) and an article on “Gusto e genio nel Bartoli” (On style and genius in Bartoli). However, the Alessandria library only owns this last article and the book Da Bacone a Kant.

Is my thesis threatening to become too vast? No, I will simply have to narrow my focus and work on a single aspect of my topic, while still consulting many of these books for background information.

At this point I consult Rocco Montano’s study “L’estetica del Rinascimento e del Barocco” (Renaissance and baroque aesthetics) published in Pensiero della Rinascenza e della Riforma (Renaissance and Reformation thought), the eleventh volume of the Grande antologia filosofica Marzorati (Mar- zorati’s great anthology of philosophy). I immediately notice that it is not only a study but also an anthology of texts, many of which are very useful for my work. And I see once again the close relationships between Renaissance scholars of Aristotle’s Poetics, the mannerists, and the baroque treatise writers. I also find a reference to Trattatisti d’arte tra Manierismo e Controriforma (Art treatise writers between Manierismo and the Counter-Reformation), a two-volume anthology published by Laterza. As I page through the catalog to find this title, I discover that the Alessandria library owns another anthology published by Laterza, Trattati di poetica e retorica del Cinquecento (Sixteenth-century treatises on poetics and rhetoric). I am not sure if my topic will require firsthand sources, but I note the book just in case. Now I know where to find it.

I return to Montano and his bibliography, and here I must do some reconstructive work, because each chapter has its own bibliography. In any case, I recognize many familiar names and, as I read, it dawns on me that I should consult some classic histories of aesthetics, such as the aforementioned Bernard Bosanquet’s, George Saintsbury’s, Marcelino Menendez y Pelayo’s, and Katherine Gilbert and Helmut Kuhn’s (1939). I also find the names of the sixteenth-century commentators of Aristotle’s Poetics that I’ve mentioned above (Robortello, Castelvetro, Scaligero, Segni, Cavalcanti, Maggi, Varchi, Vettori, Speroni, Minturno, Piccolomini, Giraldi Cinzio, etc.). I note these just in case, and I will later learn that Montano anthologized some of them, Della Volpe others, and the Laterza anthology others yet.

Montano’s bibliography refers me once again to Ma- nierismo. Panofky’s Idea continues to reappear as a pressing critical reference, and so does Morpurgo-Tagliabue’s essay “Aristotelismo e Barocco.” I wonder if I should become more informed on mannerist treatise writers like Sebastiano Serlio, Lodovico Dolce, Federico Zuccari, Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, and Giorgio Vasari; but this would lead me to the figurative arts and architecture. Perhaps some classic critical texts like Wolfflin’s, Panofsky’s, Schlosser’s, or Battisti’s more recent one would suffice. I must also note the importance of non-Italian authors like Sidney, Shakespeare, and Cervantes. Finally, I find in Montano’s bibliography familiar names cited as having authored fundamental critical studies: Curtius, Schlosser, and Hauser, as well as Italians like Calca- terra, Getto, Anceschi, Praz, Ulivi, Marzot, and Raimondi. The circle is tightening. Some names are cited everywhere.

To catch my breath, I return to the author catalog and begin to page through it. I find important books in German, most of which are also available in English translation: Panofsky’s Idea, Ernst Curtius’s famous European Literature and the Latin Middle Ages, Schlosser’s Die Kunstliteratur (Art literature), and, while I am looking for Hauser’s The Social History of Art, Hauser’s fundamental volume Mannerism: The Crisis of the Renaissance and the Origin of Modern Art.

Realizing that I must somehow read Aristotle’s Rhetoric and Poetics, I look for Aristotle in the author catalog. I am surprised to find 15 antiquarian editions of the Rhetoric published between 1515 and 1837: one with Ermolao Barbaro’s commentary; another, Bernardo Segni’s translation; another with Averroes and Alessandro Piccolomini’s paraphrases; and the Loeb English edition with the parallel Greek text. The Italian edition published by Laterza is absent. As far as the Poetics goes, there are also various editions, including one with Castelvetro’s and Robortello’s sixteenth-century commentaries, the Loeb edition with the parallel Greek text, and Augusto Rostagni’s and Manara Valgimigli’s two modern Italian translations. This is more than enough. In fact, it is enough for a thesis about Renaissance commentaries on the Poetics. But let us not digress.

From various hints in the texts I have consulted, I realize that some observations made by historians Francesco Milizia and Lodovico Antonio Muratori, and by the humanist Girolamo Fracastoro, are also relevant to my thesis. I search for their names in the author catalog, and I learn that the Alessandria library owns antiquarian editions of these authors. I then find Della Volpe’s Poetica del Cinquecento (Sixteenth-century poetics), Santangelo’s Il secentismo nella critica (Criticism on secentismo), and Zonta’s article “Rinasci- mento, aristotelismo e barocco” (A note on the Renaissance, Aristotelianism, and the baroque). Through the name of Helmuth Hatzfeld, I find a multiauthor volume that is interesting in many other respects, La critica stilistica e il barocco letterario. Atti del secondo Congresso internazionale di studi ita- liani (Stylistic criticism and the literary baroque. Proceedings of the second international conference of Italian studies), that was published in Florence in 1957. I am disappointed to find that the Alessandria library does not own one of Carmine Jannaco’s apparently important works, and also Il Sei- cento (The seventeenth century), a volume of the history of literature published by Vallardi. The library also does not own Praz’s books, Rousset’s and Tapie’s studies, the oft-quoted volume Retorica e Barocco with Morpurgo-Tagliabue’s essay, and the works of Eugenio D’Ors and Menendez y Pelayo. In a nutshell, the Alessandria library is not the Library of Congress in Washington, nor the Braidense Library in Milan, but all in all I have already secured 35 books, a decent beginning. Nor is this the end of my research.

In fact, sometimes a single text can solve a whole series of problems. As I continue checking the author catalog, I decide (since it is there, and since it appears to be a fundamental reference work) to take a look at Giovanni Getto’s “La polemica sul barocco” (The polemic on the baroque), in the first volume of the 1956 miscellaneous work Let- teratura italiana. Le correnti (The currents of Italian literature). I quickly notice that the study is almost a hundred pages long and exceptionally important, because it narrates the entire controversy on baroque style. I notice the names of major Italian writers and intellectuals who have been discussing the baroque from the seventeenth to the twentieth century: Giovanni Vincenzo Gravina, Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Girolamo Tiraboschi, Saverio Bettinelli, Giuseppe Baretti, Vittorio Alfieri, Melchiorre Cesarotti, Cesare Cantu, Vincenzo Gioberti, Francesco De Sanctis, Alessandro Manzoni, Giuseppe Mazzini, Giacomo Leopardi, Giosue Carducci, up to the twentieth-century writer Curzio Malaparte and the other authors that I have already noted. And Getto quotes long excerpts from many of these authors, which clarifies an issue for me: if I am to write a thesis on the historical controversy on the baroque, it should be of high scientific originality, it will require many years of work, and its purpose must be precisely to prove that Getto’s inquiry has been insufficient, or was carried out from a faulty perspective. For a thesis of this kind, I must explore all of these authors. However, works of this kind generally require more experience than that of our hypothetical student in this experiment. If instead I work on the baroque texts, or the contemporary interpretations of these texts, I will not be expected to complete such an immense project (a project that Getto has already done, and done excellently).

Now, Getto’s work provides me with sufficient documentation for the background of my thesis, if not on its specific topic. Extensive works such as Getto’s must generate a series of separate index cards. In other words, I will write an index card on Muratori, one on Cesarotti, one on Leopardi, and so on. I will record the work in which they expressed their opinions on the baroque, and I will copy Getto’s summary onto each index card, with relevant quotes. (Naturally, I will also note that I took the material from Getto’s essay.) If I eventually choose to use this material in my thesis, I must honestly and prudently indicate in a footnote “as quoted in Getto” because I will be using secondhand information. In fact, since we are modeling research done with few means and little time, I will not have time to check the quote against its original source. Therefore, I will not be responsible for the quote’s possible imperfections. I will faithfully declare that I took it from another scholar, I will not pretend that I have seen the original information, and I will not have to worry. However, ideally the student would have the means to check each quote with the original text.

Having altered my course, the only authors I must not ignore at this point are the baroque authors on whom I will write my thesis. I must now search for these baroque authors because, as we have said in section 3.1.2, a thesis must also have primary sources. I cannot write about the treatise writers if I do not read them in their original form. I can trust the critical studies on the mannerist theorists of the figurative arts because they do not constitute the focus of my research, but I cannot ignore a central figure of baroque poetics such as Tesauro.

So let us now turn to the baroque treatise writers. First of all, there is Ezio Raimondi’s anthology Trattatisti e nar- ratori del Seicento (Seventeenth-century treatise and narrative prose writers) published by Ricciardi that contains 100 pages of Tesauro’s Cannocchiale aristotelico, 60 pages of Peregrini, and 60 of Sforza Pallavicino. If I were writing a 30-page term paper instead of a thesis, this anthology would be more than sufficient. But for my thesis, I also want the entire treatises. Among them I need at least: Emanuele Tesauro, Il cannocchiale aristotelico; Matteo Peregrini, Delle acutezze (On acuities) and I fonti dell’ingegno ridotti a arte (The art of wit and its sources); Cardinal Sforza Pallavicino, Del bene (On the good) and Trattato dello stile e del dialogo (Treatise on style and dialogue). I begin to search for these in the “special collection” section of the author catalog, and I find two editions of the Cannocchiale, one from 1670 and the other from 1685. It is a real pity that the first 1654 edition is absent, all the more since I learned that content has been added to the various editions. I do find two nineteenth-century editions of Sforza Pallavicino’s complete works, but I do not find Peregrini. (This is unfortunate, but I am consoled by the 60 pages of his work anthologized by Raimondi.)

Incidentally, in some of the critical texts I previously consulted, I found scattered traces of Agostino Mascardi’s 1636 treatise De l’arte istorica (On the art of history), a work that makes many observations on the art of writing but is not included in these texts among the items of baroque treatise writing. Here in Alessandria there are five editions, three from the seventeenth and two from the nineteenth century. Should I write a thesis on Mascardi? If I think about it, this is not such a strange question. If a student cannot travel far from his home, he must work with the material that is locally available. Once, a philosophy professor told me that he had written a book on a specific German philosopher only because his institute had acquired the entire new edition of the philosopher’s complete works. Otherwise he would have studied a different author. Certainly not a passionate scholarly endeavor, but it happens.

Now, let us rest on our oars. What have I done here in Alessandria? I put together a critical bibliography that, to be conservative, includes at least 300 titles, if I record all the references I found. In the end, in Alessandria I found more than 30 of these 300 titles, in addition to original texts of at least two of the authors I could study, Tesauro and Sforza Pallavicino. This is not bad for a small city. But is it enough for my thesis?

Let us answer this question candidly. If I were to write a thesis in three months and rely mostly on indirect sources, these 30 titles would be enough. The books I have not found are probably quoted in those I have found, so if I assembled my survey effectively, I could build a solid argument. The trouble would be the bibliography; if I include only the texts that I actually read in their original form, my advisor could accuse me of neglecting a fundamental text. And what if I cheat? We have already seen how this process is both unethical and imprudent.

I do know one thing for certain: for the first three months I can easily work locally, between sessions in the library and at home with books that I’ve borrowed. I must remember that reference books and very old books do not circulate, nor do volumes of periodicals (but for these, I can work with photocopies). But I can borrow most other kinds of books. In the following months, I could travel to the city of my university for some intensive sessions, and I could easily work locally from September to December. Also, in Alessandria I could find editions of all the texts by Tesauro and Sforza Pallavicino. Better still, I should ask myself if it would not be better to gamble everything on only one of these two authors, by working directly with the original text and using the bibliographical material I found for background information. Afterward, I will have to determine what other books I need, and travel to Turin or Genoa to find them. With a little luck I will eventually find everything I need. And thanks to the fact that I’ve chosen an Italian topic, I have avoided the need to travel, say, to Paris or Oxford.

Nevertheless, these are difficult decisions to make. Once I have created the bibliography, it would be wise to return to the (hypothetical) advisor and show him what I have. He will be able to suggest appropriate solutions to help me narrow the scope, and tell me which books are absolutely necessary. If I am unable to find some of these in Alessandria, I can ask the librarian if the Alessandria library can borrow them from other libraries. I can also travel to the university library, where I might identify a series of books and articles. I would lack the time to read them but, for the articles, the Alessandria library could write the university library and request photocopies. An important article of 20 pages would cost me a couple of dollars plus shipping costs.

In theory, I could make a different decision. In Alessandria, I have some pre-1900 editions of two major baroque treatise authors, and a sufficient number of critical texts. These are enough to understand these two authors, if not to say something new on a historiographical or philological level. (If there were at least Tesauro’s first edition of II can- nocchiale aristotelico, I could write a comparison between the three seventeenth-century editions.) Let us suppose that I explore no more than four or five books tracing contemporary theories of metaphor. For these, I would suggest: Jakob- son’s Preliminaries to Speech Analysis, the Liege Groupe p’s A General Rhetoric, and Albert Henry’s Metonymie et meta- phore (Metonym and metaphor). Here, I have the elements to trace a structuralist history of the metaphor. And they are all books available on the market, they cost about 11 dollars altogether, and they have been translated into Italian. At this point, I could even compare the modern theories of metaphor with the baroque theories. For a work of this kind, I might possibly use Aristotle’s texts, Tesauro, 30 or so studies on Tesauro, and the three contemporary reference texts to put together an intelligent thesis, with peaks of originality and accurate references to the baroque, but no claim to philological discoveries. And all this without leaving Alessandria, except to find in Turin or Genoa no more than two or three fundamental books that were missing in Alessandria.

But these are all hypotheses. I could become so fascinated with my research that I choose to dedicate not one but three years to the study of the baroque; or I could take out a loan or look for a grant to study at a more relaxed pace. Do not expect this book to tell you what to put in your thesis, or what to do with your life. What I set out to demonstrate (and I think I did demonstrate) with this experiment is that a student can arrive at a small library with little knowledge on a topic and, after three afternoons, can acquire sufficiently clear and complete ideas. In other words, it is no excuse to say, “I live in a small city, I do not have the books, I do not know where to start, and nobody is helping me.”

Naturally the student must choose topics that lend themselves to this game. For example, a thesis on Kripke and Hintikka’s logic of possible worlds may not have been a wise choice for our hypothetical student. In fact I did some research on this topic in Alessandria, and it cost me little time. A first look for “logic” in the subject catalog revealed that the library has at least 15 notable books on formal logic, including works by Tarski, Lukasiewicz, Quine, some handbooks, and some studies of Ettore Casari, Wittgenstein, Strawson, etc. But predictably, it has nothing on the most recent theories of modal logic, material that is found mostly in specialized journals and is even absent from some university libraries. However, on purpose I chose a topic that nobody would have taken on during their final year without some kind of previous knowledge, or without already owning some fundamental books on the topic.

I’m not saying that such a topic is only for students who have the resources to purchase books and for frequent travel to larger libraries. I know a student who was not rich, but who wrote a thesis on a similar topic by staying in a religious hostel and purchasing very few books. Admittedly, despite his small sacrifices, his family supported him and he was able to devote himself full time to this project because he didn’t have to work. There is no thesis that is intrinsically for rich students, because even the student who chooses “The Variations of Beach Fashion in Acapulco over a Five-Year Period” can always search for a foundation willing to sponsor such a research project. This said, a student should obviously avoid certain topics if he is in a particularly challenging situation. For this reason, I am trying to demonstrate here how to cook a meal with meat and potatoes, if not with gourmet ingredients.

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

1 Oct 2021

1 Oct 2021

2 Oct 2021

2 Oct 2021

2 Oct 2021

1 Oct 2021