In many disciplines (and with increasing frequency) authors use a system that allows them to eliminate all reference notes, preserving only content notes and cross-references. This system presupposes that the final bibliography is organized by authors’ names, and includes the date of publication of the first edition of the book or article. Here is an example of a bibliographical entry in a thesis that uses the author-date system:

Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

What does this bibliography entry allow you to do? When you must discuss this book in the text, you can eliminate the entire footnote (the superscript note reference number in the text, the footnote itself, and the reference in the footnote) and proceed as follows:

As Chomsky wrote, “mathematical study of formal properties of grammars is, very likely, an area of linguistics of great potential” (1965, 62).

or

“It is quite apparent that current theories of syntax and semantics are highly fragmentary and tentative, and that they involve open questions of a fundamental nature” (Chomsky 1965, 148).

When the reader checks the final bibliography, he understands that “(Chomsky 1965, 148)” indicates “page 148 of Noam Chomsky’s 1965 book Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, …”

This system allows you to prune the text of the majority of the notes. In addition, it means that, at the writing stage, you only need to document a book once. For this reason, this system is especially appropriate when the student must constantly cite many books, or cite the same book often, allowing him to avoid annoying little notes full of “Ibid.” This system is indispensable even for a student writing a condensed review of the critical literature on a particular topic. For example, consider a sentence like this:

Stumpf (1945, 88-100), Rigabue (1956), Azzimonti (1957), Forlimpopoli (1967), Colacicchi (1968), Poggibonsi (1972), and Gzbiniewsky (1975) have extensively treated the issue, while Barbapedana (1950), Fugazza (1967), and Ingrassia (1970) have completely ignored it.

If you had to insert a reference note for each of these citations, you would have quite a crowded page. In addition, the reader would be deprived of the temporal sequence that clearly illustrates the chronological record of interest in the issue.

However, the author-date system works only under certain conditions:

- The bibliography must be homogeneous and specialized, and readers of your work should already be familiar with your bibliography. If the condensed literature review in the example above referred, suppose, to the sexual behavior of the order of amphibians known as Batrachia (a most specialized topic), it would be presumed that the reader knows at a glance that “Ingrassia 1970″ means the volume Birth Control among the Batrachia (or that he knows, at least intuitively, that it is one of Ingrassia’s most recent works, structured differently from his well-known works of the 1950s). If instead you are writing, for example, a thesis on Italian culture in the first half of the twentieth century, in which you will cite novelists, poets, politicians, philosophers, and economists, the author-date system no longer works well because few readers can recognize a book by its date of publication alone (although they can refer to the bibliography for this information). Even if the reader is a specialist in one field, he will probably not recognize works outside that field.

- The bibliography in question must be modern, or at least of the last two centuries. In a study of Greek philosophy it is not conventional to cite a book by Aristotle by its year of publication, for obvious reasons.

- The bibliography must be scholarly/academic. It is not conventional to write “Moravia 1929″ to indicate Alberto Moravia’s best-selling Italian novel The Indifferent Ones.

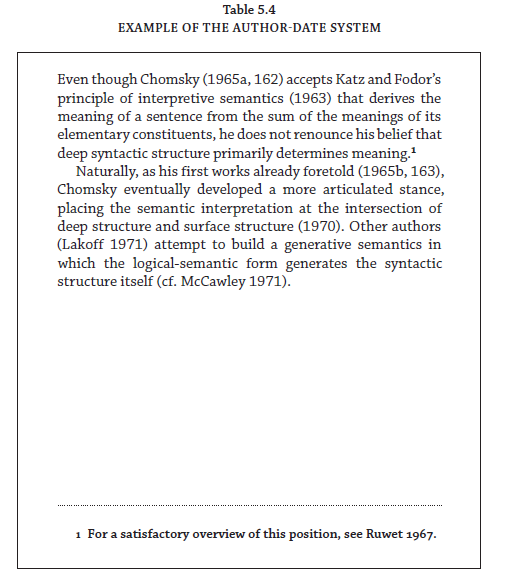

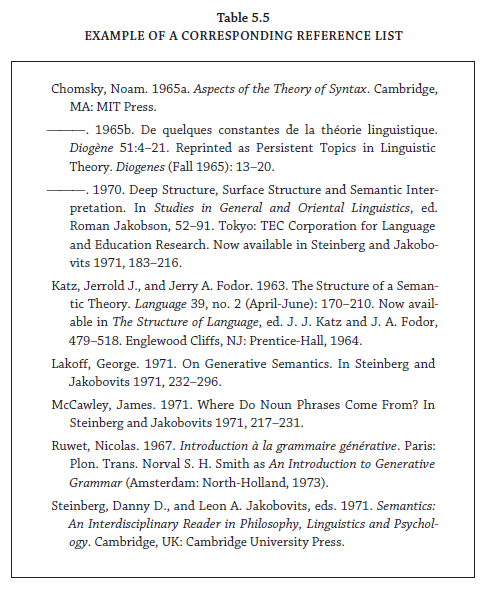

In table 5.4 you will see the same page presented in table 5.2, but reformulated according to the author-date system. You will see immediately that it is shorter, with only one note instead of six. The corresponding reference list (table 5.5) is slightly longer, but also clearer. It is easy to see the temporal sequence of an author’s works (you may have noticed that when two works by the same author appear in the same year, they are distinguished by adding lowercase letters to their year of publication), and the internal references require less information and are more direct.

Also, notice how I have dealt with multiple articles that appear in the same miscellaneous volume: I have recorded a single entry for each of these, but also a separate entry for the miscellaneous volume itself. For example, in addition to entries for the articles by Chomsky, Lakoff, and McCaw- ley, I have included a separate entry for the volume edited by Steinberg and Jakobovits in which these articles appear. But sometimes my thesis cites only one of many articles in a miscellaneous volume. In this case, I have integrated that volume’s reference into the entry for the single article I cite in my thesis. For example, I have integrated the reference to The Structure of Language edited by Katz and Fodor into the entry of the article “The Structure of a Semantic Theory” by the same authors, because the latter is the only article I cite from the former.

You will also notice that the author-date system shows at a glance when a particular text was published for the first time, even if we usually encounter this text in the form of more recent editions. For this reason, this system is useful in homogeneous treatments of a topic in specific disciplines, since in these fields it is often important to know who proposed a certain theory for the first time, or who completed certain empirical research for the first time.

There is a final reason to use the author-date system when possible. Suppose you have finished writing your thesis, and you have typewritten the final draft with many footnotes. Even if you started numbering your notes over again at the beginning of each chapter, a particular chapter may require as many as 100 notes. Suddenly you notice that you have neglected to cite an important author whom you cannot afford to ignore, and whom you must cite at the beginning of this chapter. You must now insert the new note and change 100 numbers. With the author-date system, you do not have this problem; simply insert the name and the date of publication in parentheses, and then add the item to the general bibliography (in pen, or by retyping only a single page). Even if you have not finished typewriting your thesis, inserting a note that you have forgotten still requires renumbering and often presents other annoying formatting issues, whereas with the author-date system you will have few troubles in this area.

If you use the author-date system in a thesis with a homogeneous bibliography, you can be even more succinct by using multiple abbreviations for journals, manuals, and conference proceedings. Below are two examples from two bibliographies, one in the natural sciences, the other in medicine. (Do not ask me what these bibliographical entries mean. Presumably readers in these fields will understand them.)

Mesnil, F. 1896. Etudes de morphologie externe chez les Annelides.

Bull. Sci. France Belg. 29:110-287.

Adler, P. 1958. Studies on the eruption of the permanent teeth. Acta

Genet. Stat. Med. 8:78-94.

Source: Eco Umberto, Farina Caterina Mongiat, Farina Geoff (2015), How to write a thesis, The MIT Press.

Well I truly liked studying it. This information provided by you is very helpful for proper planning.