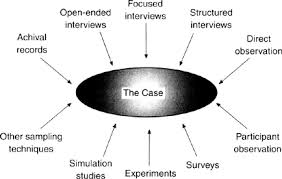

Case studies are a popular research method in business area. Case studies aim to analyze specific issues within the boundaries of a specific environment, situation or organization.

A case study involves an up-close, in-depth, and detailed examination of a particular case or cases, within a real-world context. For example, case studies in medicine may focus on an individual patient or ailment; case studies in business might cover a particular firm’s strategy or a broader market; similarly, case studies in politics can range from a narrow happening over time (e.g., a specific political campaign) to an enormous undertaking (e.g., a World War).

Generally, a case study can highlight nearly any individual, group, organization, event, belief system, or action. A case study does not necessarily have to be one observation (N=1), but may include many observations (one or multiple individuals and entities across multiple time periods, all within the same case study).

Case study research has been extensively practiced in both the social and natural sciences.

Main contentsSee more from basic to advanced

Case Study Research Designs

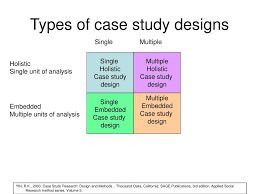

As with other social science methods, no single research design dominates case study research. Case studies can use at least four types of designs. First, there may be a “no theory first” type of case study design, which is closely connected to Kathleen M. Eisenhardt’s methodological work. A second type of research design highlights the distinction between single- and multiple-case studies, following Robert K. Yin’s guidelines and extensive examples. A third design deals with a “social construction of reality”, represented by the work of Robert E. Stake. Finally, the design rationale for a case study may be to identify “anomalies”. A representative scholar of this design is Michael Burawoy. Each of these four designs may lead to different applications, and understanding their sometimes unique ontological and epistemological assumptions becomes important. However, although the designs can have substantial methodological differences, the designs also can be used in explicitly acknowledged combinations with each other.

While case studies can be intended to provide bounded explanations of single cases or phenomena, they are often intended to theoretical insights about the features of a broader population.

Case Selection and Structure

Case selection in case study research is generally intended to both find cases that are a representative sample and which have variations on the dimensions of theoretical interest. Using that is solely representative, such as an average or typical case is often not the richest in information. In clarifying lines of history and causation it is more useful to select subjects that offer an interesting, unusual or particularly revealing set of circumstances. A case selection that is based on representativeness will seldom be able to produce these kinds of insights.

While random selection of cases is a valid case selection strategy in large-N research, there is a consensus among scholars that it risks generating serious biases in small-N research. Cases should generally be chosen that have a high expected information gain. For example, outlier cases (those which are extreme, deviant or atypical) can reveal more information than the potentially representative case. A case may also be chosen because of the inherent interest of the case or the circumstances surrounding it. Alternatively it may be chosen because of researchers’ in-depth local knowledge; where researchers have this local knowledge they are in a position to “soak and poke” as Richard Fenno put it, and thereby to offer reasoned lines of explanation based on this rich knowledge of setting and circumstances.

Beyond decisions about case selection and the subject and object of the study, decisions need to be made about purpose, approach and process in the case study. Gary Thomas thus proposes a typology for the case study wherein purposes are first identified (evaluative or exploratory), then approaches are delineated (theory-testing, theory-building or illustrative), then processes are decided upon, with a principal choice being between whether the study is to be single or multiple, and choices also about whether the study is to be retrospective, snapshot or diachronic, and whether it is nested, parallel or sequential.

John Gerring and Jason Seawright list seven case selection strategies:

Typical cases are cases that exemplify a stable cross-case relationship. These cases are representative of the larger population of cases, and the purpose of the study is to look within the case rather than compare it with other cases.

- Diverse cases are cases that have variation on the relevant X and Y variables. Due to the range of variation on the relevant variables, these cases are representative of the full population of cases.

- Extreme cases are cases that have an extreme value on the X or Y variable relative to other cases.

- Deviant cases are cases that defy existing theories and common sense. They not only have extreme values on X or Y (like extreme cases), but defy existing knowledge about causal relations.

- Influential cases are cases that are central to a model or theory (for example, Nazi Germany in theories of fascism and the far-right).

- Most similar cases are cases that are similar on all the independent variables, except the one of interest to the researcher.

- Most different cases are cases that are different on all the independent variables, except the one of interest to the researcher.

For theoretical discovery, Jason Seawright recommends using deviant cases or extreme cases that have an extreme value on the X variable.

Arend Lijphart, and Harry Eckstein identified five types of case study research designs (depending on the research objectives), Alexander George and Andrew Bennett added a sixth category:

- In atheoretical (or configurative idiographic) case studies the goal is to describe a case very well, but not to contribute to a theory.

- In interpretative (or disciplined configurative) case studies the goal is to use established theories to explain a specific case.

- In hypothesis-generating (or heuristic) case studies the goal is to inductively identify new variables, hypotheses, causal mechanisms and causal paths.

- In theory testing case studies the goal is to assess the validity and scope conditions of existing theories.

- In plausibility probes the goal is to assess the plausibility of new hypotheses and theories.

- In building block studies of types or subtypes the goal is to identify common patterns across cases.

In terms of case selection, Gary King, Robert Keohane, and Sidney Verba warn against “selecting on the dependent variable”. They argue for example that researchers cannot make valid causal inferences about war outbreak by only looking at instances where war did happen (the researcher should also look at cases where war did not happen). Scholars of qualitative methods have disputed this claim, however. They argue that selecting on the dependent variable can be useful depending on the purposes of the research.

King, Keohane and Verba argue that there is no methodological problem in selecting on the explanatory variable, however. They do warn about multicollinearity (choosing two or more explanatory variables that perfectly correlate with each other).

Uses and Limits

Uses

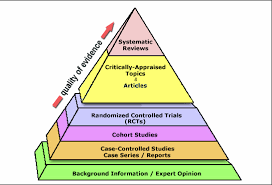

Case studies have commonly been seen as a fruitful way to come up hypotheses and generate theories. Case studies are also useful for formulating concepts, which are an important aspect of theory construction. The concepts used in qualitative research will tend to have higher conceptual validity than concepts used in quantitative research (due to conceptual stretching: the unintentional comparison of dissimilar cases). Case studies add descriptive richness. Case studies are suited to explain outcomes in individual cases, which is something that quantitative methods are less equipped to do. Through fine-gained knowledge and description, case studies can fully specify the causal mechanisms in a way that may be harder in a large-N study. In terms of identifying “causal mechanisms”, some scholars distinguish between “weak” and “strong chains”. Strong chains actively connect elements of the causal chain to produce an outcome whereas weak chains are just intervening variables.

Case studies of cases that defy existing theoretical expectations may contribute knowledge by delineating why the cases violate theoretical predictions and specifying the scope conditions of the theory Case studies are useful in situations of causal complexity where there is equifinality, complex interaction effects and path dependency Case studies can identify necessary and insufficient conditions, as well as complex combinations of necessary and sufficient conditions. They argue that case studies may also be useful in identifying the scope conditions of a theory: whether variables are sufficient or necessary to bring about an outcome.

Limitations

Designing Social Inquiry, an influential 1994 book written by Gary King, Robert Keohane, and Sidney Verba, primarily applies lessons from regression-oriented analysis to qualitative research, arguing that the same logics of causal inference can be used in both types of research. The authors’ recommendation is to increase the number of observations (a recommendation that Barbara Geddes also makes in Paradigms and Sand Castles), because few observations make it harder to estimate multiple causal effects, as well as increase the risk that there is measurement error, and that an event in a single case was caused by random error or unobservable factors. KKV sees process-tracing and qualitative research as being “unable to yield strong causal inference” due to the fact that qualitative scholars would struggle with determining which of many intervening variables truly links the independent variable with a dependent variable. The primary problem is that qualitative research lacks a sufficient number of observations to properly estimate the effects of an independent variable. They write that the number of observations could be increased through various means, but that would simultaneously lead to another problem: that the number of variables would increase and thus reduce degrees of freedom.

The purported “degrees of freedom” problem that KKV identify is widely considered flawed; while quantitative scholars try to aggregate variables to reduce the number of variables and thus increase the degrees of freedom, qualitative scholars intentionally want their variables to have many different attributes and complexity. For example, James Mahoney writes, “the Bayesian nature of process tracing explains why it is inappropriate to view qualitative research as suffering from a small-N problem and certain standard causal identification problems.” By using Bayesian probability, it may be possible to makes strong causal inferences from a small sliver of data.

A commonly described limit of case studies is that they do not lend themselves to generalizability. Some scholars, such as Bent Flyvbjerg, have pushed back on that notion.

As small-N research should not rely on random sampling, scholars must be careful in avoiding selection bias when picking suitable cases. A common criticism of qualitative scholarship is that cases are chosen because they are consistent with the scholar’s preconceived notions, resulting in biased research.

Alexander George and Andrew Bennett note that a common problem in case study research is that of reconciling conflicting interpretations of the same data.

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021

13 Aug 2021