There are two general categories of business models: standard business models and disruptive business models.5 Next, we provide details about each model.

1. Standard business models

The first category is standard business models. This type of model is used com- monly by existing firms as well as by those launching an entrepreneurial ven- ture. Standard business models depict existing plans or recipes firms can use to determine how they will create, deliver, and capture value for their stakehold- ers. There are a number of standard or common business models. An abbrevi- ated list is shown in Table 4.1. Most of the standard business models, with the exception of the freemium model, have been in place for some time. In fact, many of the business models utilized by online firms were originally developed by of- fline firms, and simply transferred to the Internet. For example, Amazon did not invent a new business model. It took the mail order business model, pioneered years ago by Sears Roebuck and Company, and moved it online. Similarly, eBay did not invent the auction business model—that has been in existence for cen- turies. It moved the auction format online. What Amazon.com and eBay did do, however, which is common among successful start-ups, is adopt a standard business model and build upon it in one or more meaningful ways to produce a new way of creating value. Birchbox, for example, adopted the subscription busi- ness model and then built upon it in novel ways. This firm provides its subscrib- ers a monthly assortment of cosmetic and skin care samples in hopes of enticing them to buy full-sized versions of the same products. Its cost structure is low because it operates via the Internet and many of the samples that it distributes are provided for free by companies that want to get their products in front of Birchbox’s unique clientele. The other elements of Birchbox’s business model are supportive of its basic premise. The multifaceted “value” that Birchbox’s business model creates is that it presents products to women that they wouldn’t have oth- erwise tried. Through this model, Birchbox creates two revenue streams for itself (i.e., the subscription service and online sales), and it creates additional sales for the companies that provide the samples that Birchbox disseminates to its sub- scribers. You can read more about Birchbox in Case 6.1.

It is important to understand that there is no perfect business model.6 Each of the standard models has inherent strengths and weaknesses. For example, the strength of the subscription business model is recurring revenue. Birchbox has approximately 400,000 subscribers who pay $10 per month. As a result, if Birchbox maintains its subscriber base, it would know that it had a minimum of $4 million in revenue each month. The disadvantage of the subscription business model is “churn.” Churn refers to the number of subscribers that a subscription-based business loses each month. If Birchbox losses 10 percent of its subscribers each month, it will need to recruit 40,000 new subscribers each month just to stay even. This is why companies that feature a subscription- based business model normally offer a high level of customer service. They want to retain as high a percentage of their subscribers as they can to lower churn and avoid the expenses involved with replacing existing customers.

It’s important to note that a firm’s business model takes it beyond its own boundaries. Her Campus’s business model, for example, is based on the idea that female college students will form My Campus chapters and voluntarily contribute content to their chapter’s website and the main Her Campus portal. The trick to getting something like this to work is to provide sufficient incentive for partners to participate. In Her Campus’s case, the local My Campus mem- bers contribute because they want to obtain experience, hone their journalistic skills, and build their résumés. Apparently, Her Campus is providing these indi- viduals a rich enough experience that it’s worth their time to participate. Many companies feature the participation of others as an integral part of their busi- ness models. An example is Apple, and in particular the Apple App Store. As of December 2013, more than 1 million apps were available through the Apple App Store, created by over 262,000 publishers. About 140 new apps are added each day. It’s a win-win situation for both Apple and the developers. The developers get access to a platform to sell their apps, while Apple shares in the revenue that’s generated. Positive scenarios like this often allow businesses to not only strengthen but to expand their business models. As a result of the success of its app store, Apple launched iAd, a platform that allows app developers to sell ad- vertising on the apps they make available via the Apple App Store. Apple shares in the revenue generated by the advertising.

Regardless of the business model a start-up is rolling out, one thing that new companies should guard themselves against is thinking that one particu- lar business model is a “homerun” regardless of circumstances.7 In this sense, the issues discussed in Chapters 1–3 still apply, meaning, for example, that the strength of the opportunity must be assessed and the feasibility of the idea must be validated. The What Went Wrong feature nearby draws attention to this point. Even though the peer-to-peer business model is currently hot, with homeruns such as Airbnb and Uber, utilizing the peer-to-peer business model is not sufficient to guarantee firm success.

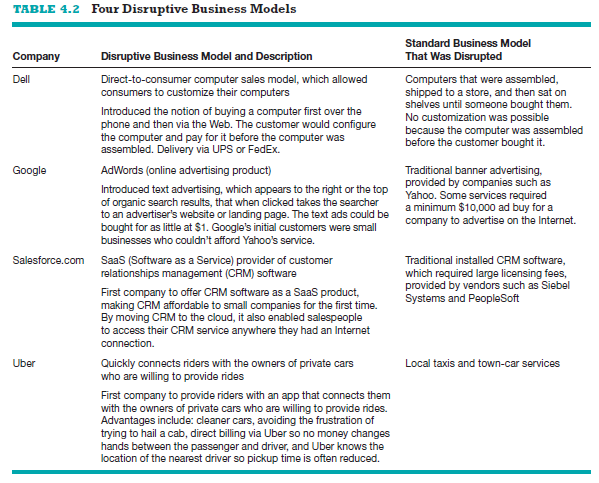

2. Disruptive business models

The second category is disruptive business models. Disruptive business models, which are rare, are ones that do not fit the profile of a standard busi- ness model, and are impactful enough that they disrupt or change the way business is conducted in an industry or an important niche within an indus- try.8 In Table 4.2, we describe actual disruptive business models that were used by four different companies.

There are three types of disruptive business models. The first type is called new market disruption. A new market disruption addresses a market that previously wasn’t served. An example is Google and its AdWords program. AdWords allows an advertiser to buy keywords on Google’s home page, which triggers text-based ads to the side of (and sometimes above) the search results when the keyword is used. So, if you type the words “organic snacks” into the Google search bar, you will see ads paid for by companies that have organic snacks to sell. The ads are usually paid for on a pay-per-click basis. The cost of keywords varies depending on the popularity of the word. Prior to the ad- vent of AdWords, online advertising was cost prohibitive for small businesses. At one time Yahoo, for example, required advertisers to spend at least $5,000 creating a compelling banner ad and $10,000 for a minimum ad buy. AdWords changed that. Its customers could set up a budget and spend as little as $1 per day (depending on the keywords that they purchased). Thus, AdWords was a new market-disruptive business model in that it provided a way for small busi- nesses, in large numbers, to advertise online.

The second type of disruptive business model is referred to as a low-end market disruption. This is a type of disruption that was elegantly written about by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen in the book The Innovator’s Dilemma.9

Low-end disruption is possible when the firms in an industry continue to improve products or services to the point where they are actually better than a sizable portion of their clientele needs or desires. This “performance oversupply” creates a vacuum that provides an opportunity for simple, typically low-cost business models to exist. Examples here include Southwest Airlines in the United States and Ryanair in Europe. Southwest created its point-to-point, low-cost, no-frills business model as an alternative to higher-end service offerings provided by leg- acy carriers such as United and American. By actually offering what some would conclude is inferior service relative to its competitors, Southwest was able to at- tract a large clientele that still wanted a safe and comfortable ride, but were will- ing to trade off amenities for a lower fare. Low-end disruptive business models are also introduced to offer a simpler, cheaper, or more convenient way to perform an everyday task. If a start-up goes this route, the advantages must be compelling and the company must strike a nerve for disruption to take place. An example of a firm that’s pulled this off is Uber, a 2009 start-up that connects people needing a ride with the owners of private cars willing to provide rides. Uber, which is the subject of Case 14.1, provides a compelling set of features—cars are ordered by sending a text message or via an app, customers can track their reserved car’s location, payment is made through the app so no cash trades hands between the passenger and the driver, and Uber maintains strict quality standards for the cars and drivers that participate in its service. Uber not only offers a cheaper and more convenient way to perform an everyday task (i.e., getting a ride), but has also struck a nerve.10 The taxi industry scores low on most measures of customer satisfaction, so consumers were eager to try something new. Uber also appeals to technologically savvy people, who see a big advantage in using an app to order a ride as opposed to the often frustrating process of hailing a cab.

Source: Barringer Bruce R, Ireland R Duane (2015), Entrepreneurship: successfully launching new ventures, Pearson; 5th edition.

Appreciating the time and effort you put into your website and detailed information you present. It’s good to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same out of date rehashed information. Excellent read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m including your RSS feeds to my Google account.