The benefits of a global enterprise system for constituent entry strategies are most evident when managers can design an effective marketing plan for a group of countries. But to do so, managers need to search for country markets that will respond to a standard marketing program. When done right, grouping facilitates entry planning, in addition to enhancing the profit contributions of constituent entry strategies.

It is correct to assert that each country, each market, and each consumer or user is unique at some level of analysis. It is easy, therefore, for managers to deny the usefulness of country grouping. This is particularly true for country managers who are quick to proclaim the uniqueness of their own countries and markets in opposing corporate marketing plans. But at issue is not the ultimate uniqueness of country markets, but rather whether certain country markets are similar enough to justify a common marketing strategy. To find out, managers should look for country groups on a global basis, because some country markets may be similar across regional lines.

1. A Sequential Model for Grouping Country Markets

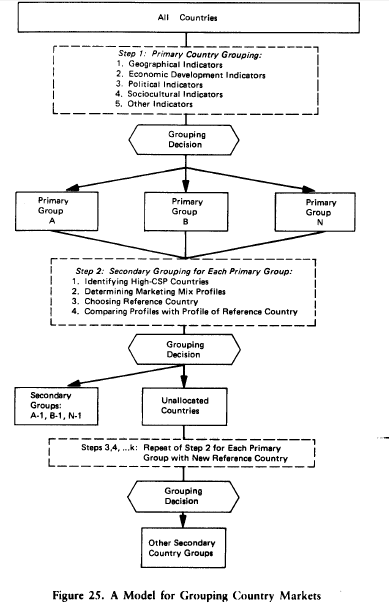

Figure 25 offers a sequential model for grouping country markets. It allows managers to determine, first, broad primary groups and, second, secondary groups within each primary group.5

Starting with all countries, managers determine a small number of primary groups by using statistical indicators of market behavior with respect to a candidate product. Although the purpose of this model is to group countries rather than choose a target country, the same multicountry statistics used for preliminary screening (such as those listed on pages 36 and 37) may be used here. Indeed, our grouping model is intimately related to the target-selection model presented in Chapter 2. Managers should regard statistical indicators as “proxies” for direct measures of market behavior, and they should select them for that purpose.

For administrative reasons, managers generally group countries by geographical area, but there is no a priori reason why countries in the same geographical area should respond to a standard marketing program in the same way. Nor is there any a priori reason why countries in different geographical areas should have different market responses. For example, markets in Australia are much more similar to markets in Canada than to markets in Indonesia, which is a geographical neighbor. In planning entry strategies, therefore, managers should not be constrained by geographical country groups used for administrative purposes. At times, certain geographical groups may be sensible from a marketing perspective, but then the reason is seldom mere physical contiguity. Most of the Western European countries form a natural market grouping not because they are next to each other but for other reasons, including membership in the EEC or EFTA (which are joined together in an industrial free-trade area) and a common level of economic development.

In classifying countries into primary groups, managers may use several kinds of indicators: geographical (apart from mere continguity), level of economic development, political, sociocultural, and others. Since a country’s level of economic development exerts a pervasive influence on market behavior, many managers will determine country groups by using per- capita income and other indicators of economic development. The most relevant grouping by political system is the distinction between market and nonmarket countries. Countries may also be grouped by sociocultural similarities, such as language, religion, education, and other attributes that influence market behavior. In placing countries in primary groups, managers may use one or more of these categories of indicators. Generally, the use of multiple indicators covering more than one category is superior to the use of a single indicator or a single category.

The number of primary country groups depends on the range of indicator values covering all countries and the ranges selected by managers to demarcate one group from another. Since primary groups are intended to be broad, their number would seldom exceed five.

The second step of the model starts the sequential process of determining secondary groups within each primary group. This step focuses only on countries with high company sales potential (CSP) that have been identified by using the target-selection model presented in Chapter 2. These countries justify the time and effort to ascertain their marketing mix profiles for the candidate product, as was done for a single target country/market in Chapter 7 (Figure 17). Next, managers choose one of the high-potential countries in each primary group as a reference country, whose marketing mix profile is used as a standard. This reference country is likely to be a country in which the global company is already marketing the candidate product or the country with the highest CSP. The marketing mix profiles of other high- CSP countries are then compared with the marketing profile of the reference country in the respective primary groups. On the basis of these pair comparisons, managers classify countries into a secondary group whose members have profiles judged similar to the reference profile, and into unallocated countries. Managers then go on to allocate all countries to secondary groups by repeating step 2 in successive steps with new reference countries.

How many steps are needed to classify all countries into secondary groups depends on the diversity in marketing mix profiles as judged by managers. At one extreme, managers may decide that common marketing strategics for any two countries would not be successful. In effect, each country is the sole member of its secondary group. At the other extreme, managers may judge a product so insensitive to local market conditions that they can place all countries in a single secondary group. However, most products fall between these two extremes: the number of secondary groups is greater than the number of primary groups but smaller than the number of high-CSP countries.

This model is intended to help managers group country markets in a systematic but economical fashion. It makes use of the natural inclination of managers to ask whether new country markets are similar to old country markets. By using, whenever possible, reference countries in which the company has ongoing marketing programs for the candidate product, the model should aid managers in making sequential choices of target markets as well as in designing common marketing strategies. But other approaches to country grouping may also prove useful, including formal methods that use computer-assisted clustering techniques, such as factor analysis, discriminant analysis, and multidimensional scaling.6 Managers should understand that no grouping method, however sophisticated, can possibly account for all the many factors that may influence marketing effectiveness in a group of countries. Ultimately, only managers make grouping decisions, and therefore they should use a grouping method (or methods) that makes sense to them, given constraints of time and of information resources. Moreover, they should be ready to revise grouping decisions in the light of actual marketing performance.

2. Standardizing Marketing Programs for Country Groups

Country grouping is the starting point for the design of marketing programs common to each country group. If grouping is done well, managers have an empirical basis for judging whether or not a common strategy in an overall marketing program or in any one of its individual elements is likely to be cost-effective for a target group.

In Chapter 2, we first discussed adapting products for foreign markets! pointing out that few companies can profitably follow a pure version of a product adaptation strategy or a product standardization strategy. That observation also pertains to other elements of the marketing mix: pricing, promotion, and distribution channels. That is to say, few companies can offer the same product lines at the same prices through the same distribution channels supported by the same promotion to a group of countries. No group of country markets is likely to show similar responses to all elements of a marketing program. On the other hand, many companies can offer, say, the same product lines or the same promotion to a group of countries while adapting other policies to national differences. Therefore, country grouping usually leads to different degrees of standardization across the several elements of the marketing mix. For example, a survey of 27 leading global companies in consumer packaged-goods industries found that although executives in 62 percent of the companies rated their total marketing program in European countries as “highly standardized,” the highest degrees of standardization occurred in brand names, the physical product, the role of middlemen, packaging, the role of the sales force, the basic advertising message, and management of the sales force, while medium degrees occurred in creative expression, type of retail outlet, and sales promotion, and the lowest degrees occurred in retail price and media allocation.7

In the face of national differences, the only reason for managers to standardize marketing policies for a group of countries is the higher profit contribution of common policies as compared to separate national policies. Earlier in this chapter, we discussed the benefits a global enterprise can achieve by fitting constituent entry strategies into its worldwide operations. But this cannot be done by ignoring national differences; it calls for informed judgments that involve trade-offs among effectiveness, costs, and risks in support of standardization/adaptation decisions.

General observation suggests that multinational companies err on the side of too little standardization rather than too much, because they let country managers plan, as well as manage, local marketing programs. But as multinational companies become more global in their orientation, standardized marketing policies will gradually replace purely local policies through a process of interactive planning. Several forces external to the individual company will also act to encourage more standardization in the future: continuing improvements in transportation and communication, the formation of new free-trade areas and customs unions, a growing convergence of living standards among several countries, an intensification of international competition, the appearance of more multinational customers, the further expansion of international travel, and the collective behavior of enterprises pursuing global strategies.8 However, this shift toward standardized marketing policies and away from local policies will fall far short of full global standardization as managers continue to cope with many significant national differences.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

You made some good points there. I did a search on the issue and found most individuals will go along with with your site.

I real pleased to find this website on bing, just what I was searching for : D as well saved to favorites.

An fascinating dialogue is worth comment. I feel that it’s best to write extra on this topic, it may not be a taboo topic but generally individuals are not sufficient to talk on such topics. To the next. Cheers