The elements of a foreign market entry strategy, as depicted in Figure 1 in Chapter 1, are the same for a global enterprise as for other international companies. The constituent entry plan always focuses on a single product (or product line) and a single foreign target market. What is different in the global enterprise is the context or internal system environment of worldwide operations in which managers make entry decisions. In such a system, managers can use experience acquired in one country for entry decisions in a second country, and they can improve the cost-effectiveness of entry decisions by coordinating them across countries.

1. Global Entry Planning Model

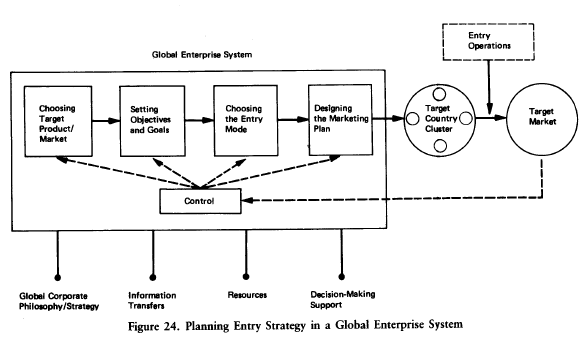

A global enterprise system influences entry decisions through (1) a global corporate philosophy and strategy, (2) information transfers, (3) resources, and (4) decision-making support.

In making entry decisions, managers are guided by an overall corporate philosophy and strategy, which expresses goals for the entire enterprise system. Constituent entry strategies must support those goals if they are to optimize profit contributions to the system; otherwise, entry strategies that are cost-effective in isolation may nonetheless be suboptimum for global operations. In sum, planners need to fit new entry strategies into existing operations.

Managers planning entry strategies in stage 4 companies obtain information transfers that originate in existing country operations.3 Subsidiaries can provide corporate managers with information on host countries and local markets that may be difficult, costly, or impossible to obtain from other sources. Apart from providing information useful in selecting new target markets, subsidiaries (and other foreign operations) originate information pertinent to the choice of candidate products and entry modes. Again, existing country marketing programs offer valuable models in designing programs for new entry strategies. For instance, advertising campaigns that have proved successful in one or more countries should be considered by managers planning new entry strategies for the same product.

In a global enterprise system, the global corporation functions as the clearinghouse for systemwide information flows. Thus the immediate source of information originating in foreign operations is likely to be corporate staff departments. Those departments also originate information (and information assessments) that can be tapped by managers making entry decisions.

The availability of system resources exerts a powerful influence on entry decisions. We are speaking here not of financial resources but rather of the capabilities of multinational research, production, logistics, and marketing operations headed by experienced managers. The candidate product itself may originate in a subsidiary in a foreign country rather than in the parent company. Even when the global enterprise has no existing operations in a new target country, the availability of multiple-country production bases can make export entry or a mixed export/investment entry more profitable than otherwise. In countries where the global enterprise already has operations, their use can drastically enhance the cost-effectiveness of a new entry strategy.

Corporate managers can also obtain decision-making support from their worldwide system environment. Corporate staff and country managers are sources of advice as well as information. As we shall observe shortly, country managers also share in entry decisions within an interactive planning process. This support generates functional, product, and geographical inputs for entry decisions to a far higher degree than would be possible if corporate line executives acted on their own.

Figure 24 depicts entry-strategy planning in a global enterprise system. Decisions on each element of the constituent entry strategy are influenced by the strategy, information transfers, resources, and decision-making support of the system. In designing entry strategies, managers have a twofold task of planning constituent strategies that will be effective in their target markets and will also make an optimum profit contribution to the worldwide system. This latter task encourages efforts to standardize entry strategies across country markets that form a group of similar markets, as shown in Figure 24. Entry-strategy elements that cannot be standardized in a cost- effective way must be adapted to individual target country markets. We shall have more to say about grouping later on.

A global enterprise system can increase the profit contributions of constituent entry strategies by lowering incremental costs and raising incremental revenues. Information transfers make for better decisions; system resources can sharply cut incremental production and marketing costs; decision-making support brings functional, product, and country expertise, to decisions; and global corporate strategy guides managers toward a full use of ongoing foreign operations in designing new entry strategies. But these benefits are not always obtained by managers. Blockages in system communication channels may impede information transfers and limit the availability of resources. Organization structures that emphasize product skills to the detriment of area skills, or vice versa, can weaken decisionmaking support. Overcentralization of decision making at the corporate level can ignore the knowledge and experience of subsidiary managers. In sum, the benefits of a global system for new entry strategies are dependent on an information network together with an organization structure that facilitates coordination across functions, products, and countries.

Benefits may also be constrained by a broad diversification of products with different technologies and end uses, although functional and geographical skills can serve all product groups in some measure. Products that must be closely adapted to individual country markets also limit the benefits of a global system. Another limitation deserves mention: exclusive reliance on information originating in existing foreign operations can cause corporate managers to ignore opportunities in new countries or new products because country managers tend to scan only the environment in their own countries for existing product lines.

2. Centralizing and Decentralizing Entry Decisions

Entry-strategy planning in a global enterprise system should be an interactive process involving managers at corporate, regional, and country levels. Interactive planning is vital to the design of effective entry strategies that take full advantage of existing worldwide operations. Highly centralized, top-down entry planning ignores the intimate knowledge of, and experience in, host countries and local markets possessed by country managers. Conversely, highly decentralized, bottom-up entry planning by autonomous country managers ignores the functional and product skills possessed by corporate managers and also fails to integrate entry strategies across countries and regions.

The argument for interactive entry planning or shared decision making in a global enterprise system does not necessarily imply that all entry decisions should be shared between corporate and subsidiary managers or shared in the same degree. Headquarters may reserve certain entry decisions to itself while delegating other entry decisions to country subsidiaries. But the great majority of entry decisions falls between these two extremes; they are made with the active participation of corporate, regional, and subsidiary managers.

Shared decision making takes many forms: the subsidiary recommends or proposes while headquarters approves or rejects; headquarters proposes, while the subsidiary accepts or rejects; headquarters consults with the subsidiary and then decides; and so on.4 In sum, corporate managers may recommend, propose, consult, review, approve, or reject while country managers may recommend, propose, consult, accept, or reject. At times, shared decision making turns into negotiations between corporate and country managers, with give and take by both sides. Even with shared decision making, all entry decisions are ultimately subject to corporate approval, because all planned expenditures by subsidiaries are subject to corporate review and approval in the annual budgeting process.

What factors determine whether a specific entry decision should be made by corporate managers, by country managers, or jointly by both? The main consideration is the potential contribution of the local skills and knowledge of country managers to that decision. If that contribution is modest or unnecessary, then corporate managers should make entry deci- sions on their own; on the other hand, if it is significant, then country managers should be brought into the decision-making process. To illustrate, country managers can seldom contribute much to decisions on entering new country markets in which the global enterprise has no current operations or to decisions on new world products, although in both instances they may provide valuable information. But country managers can contribute a great deal to decisions on the marketing program for new products in their respective countries. Because consumer products are generally more sensitive to local market conditions than industrial products, country managers assume a more prominent role in entry decision making in consumer- products companies than in industrial-products companies.

A second consideration is the size of the cash outlay required to carry out the entry decision. We can express this consideration with the following rule: corporate managers should make entry decisions when the probability times the cost of a4>ad decision made by a country manager exceeds a certain sum. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that investment entry decisions are highly centralized at the corporate level.

A third consideration is the degree of multinationality of the entry decision. Decisions involving transfers between two or more countries should be made by corporate managers, because only they can take an objective regional or global perspective. Hence decisions to source products in one country for export to another or decisions on intracorporate transfer pricing are properly centralized at headquarters. Decisions on world or “international” products that are marketed in several countries with common trademarks and brand names should also be the responsibility of headquarters. On the other hand, decisions on “local” products that are sold only in single country markets should be shared between corporate and the respective country managers. In brief, corporate managers should make entry decisions that have significant multinational dimensions, and they should share with country managers entry decisions that are primarily uninational in nature, unless the first two considerations indicate otherwise.

Because of these considerations, the global enterprise should centralize decisions on new international products. Entry mode decisions should also be centralized, because they involve two or more countries (sourcing decisions for export entry are an example), require substantial cash outlays (notably in the case of investment entry), or commit the corporation to long-term arrangements with foreign parties (as in licensing entry). In contrast, decisions on the design of the foreign marketing plan should be shared with managers in the target country, because channel, promotion, and pricing decisions are critically dependent on local country/market conditions. In concluding this section, it should also be noted that shared decision making among different corporate managers is necessary to provide the functional, product, and area skills which are vital to planning cost-effective entry strategies in a global enterprise system.

Source: Root Franklin R. (1998), Entry Strategies for International Markets, Jossey-Bass; 2nd edition.

I believe other website proprietors should take this website as an example , very clean and superb user pleasant style and design.