With all these systems and information, you might wonder how it is possible to make sense of them. How do people working in firms pull it all together, work toward common goals, and coordinate plans and actions? In addition to the types of systems we have just described, businesses need special systems to support collaboration and teamwork.

1. What Is Collaboration?

Collaboration is working with others to achieve shared and explicit goals. Collaboration focuses on task or mission accomplishment and usually takes place in a business or other organization and between businesses. You collaborate with a colleague in Tokyo who has expertise on a topic about which you know nothing. You collaborate with many colleagues in publishing a company blog. If you’re in a law firm, you collaborate with accountants in an accounting firm in servicing the needs of a client with tax problems.

Collaboration can be short-lived, lasting a few minutes, or longer term, depending on the nature of the task and the relationship among participants. Collaboration can be one-to-one or many-to-many.

Employees may collaborate in informal groups that are not a formal part of the business firm’s organizational structure, or they may be organized into formal teams. Teams have a specific mission that someone in the business assigned to them. Team members need to collaborate on the accomplishment of specific tasks and collectively achieve the team mission. The team mission might be to “win the game” or “increase online sales by 10 percent.” Teams are often short-lived, depending on the problems they tackle and the length of time needed to find a solution and accomplish the mission.

Collaboration and teamwork are more important today than ever for a variety of reasons.

- Changing nature of work. The nature of work has changed from factory manufacturing and pre-computer office work where each stage in the production process occurred independently of one another and was coordinated by supervisors. Work was organized into silos. Within a silo, work passed from one machine tool station to another, from one desktop to another, until the finished product was completed. Today, jobs require much closer coordination and interaction among the parties involved in producing the service or product. A report from the consulting firm McKinsey & Company estimated that 41 percent of the U.S. labor force is now composed of jobs where interaction (talking, e-mailing, presenting, and persuading) is the primary valueadding activity (McKinsey, 2012). Even in factories, workers today often work in production groups, or pods.

- Growth of professional work. “Interaction” jobs tend to be professional jobs in the service sector that require close coordination and collaboration. Professional jobs require substantial education and the sharing of information and opinions to get work done. Each actor on the job brings specialized expertise to the problem, and all the actors need to take one another into account in order to accomplish the job.

- Changing organization of the firm. For most of the industrial age, managers organized work in a hierarchical fashion. Orders came down the hierarchy, and responses moved back up the hierarchy. Today, work is organized into groups and teams, and the members are expected to develop their own methods for accomplishing the task. Senior managers observe and measure results but are much less likely to issue detailed orders or operating procedures. In part, this is because expertise and decision-making power have been pushed down in organizations.

- Changing scope of the firm. The work of the firm has changed from a single location to multiple locations—offices or factories throughout a region, a nation, or even around the globe. For instance, Henry Ford developed the first mass-production automobile plant at a single Dearborn, Michigan factory. In 2017, Ford employed 202,000 people at about 67 locations worldwide. With this kind of global presence, the need for close coordination of design, production, marketing, distribution, and service obviously takes on new importance and scale. Large global companies need to have teams working on a global basis.

- Emphasis on innovation. Although we tend to attribute innovations in business and science to great individuals, these great individuals are most likely working with a team of brilliant colleagues. Think of Bill Gates and Steve Jobs (founders of Microsoft and Apple), both of whom are highly regarded innovators and both of whom built strong collaborative teams to nurture and support innovation in their firms. Their initial innovations derived from close collaboration with colleagues and partners. Innovation, in other words, is a group and social process, and most innovations derive from collaboration among individuals in a lab, a business, or government agencies. Strong collaborative practices and technologies are believed to increase the rate and quality of innovation.

- Changing culture of work and business. Most research on collaboration supports the notion that diverse teams produce better outputs faster than individuals working on their own. Popular notions of the crowd (“crowdsourcing” and the “wisdom of crowds”) also provide cultural support for collaboration and teamwork.

2. What Is Social Business?

Many firms today enhance collaboration by embracing social business—the use of social networking platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and internal corporate social tools—to engage their employees, customers, and suppliers. These tools enable workers to set up profiles, form groups, and “follow” each other’s status updates. The goal of social business is to deepen interactions with groups inside and outside the firm to expedite and enhance information sharing, innovation, and decision making.

A key word in social business is conversations. Customers, suppliers, employees, managers, and even oversight agencies continually have conversations about firms, often without the knowledge of the firm or its key actors (employees and managers).

Supporters of social business argue that if firms could tune in to these conversations, they would strengthen their bonds with consumers, suppliers, and employees, increasing their emotional involvement in the firm.

All of this requires a great deal of information transparency. People need to share opinions and facts with others quite directly, without intervention from executives or others. Employees get to know directly what customers and other employees think, suppliers will learn very directly the opinions of supply chain partners, and even managers presumably will learn more directly from their employees how well they are doing. Nearly everyone involved in the creation of value will know much more about everyone else.

If such an environment could be created, it is likely to drive operational efficiencies, spur innovation, and accelerate decision making. If product designers can learn directly about how their products are doing in the market in real time, based on consumer feedback, they can speed up the redesign process. If employees can use social connections inside and outside the company to capture new knowledge and insights, they will be able to work more efficiently and solve more business problems.

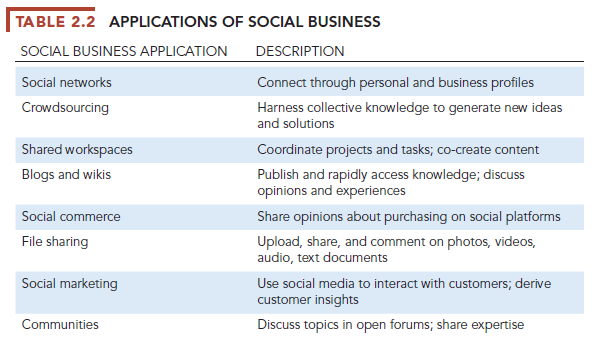

Table 2.2 describes important applications of social business inside and outside the firm. This chapter focuses on enterprise social business—its internal corporate uses.

3. Business Benefits of Collaboration and Social Business

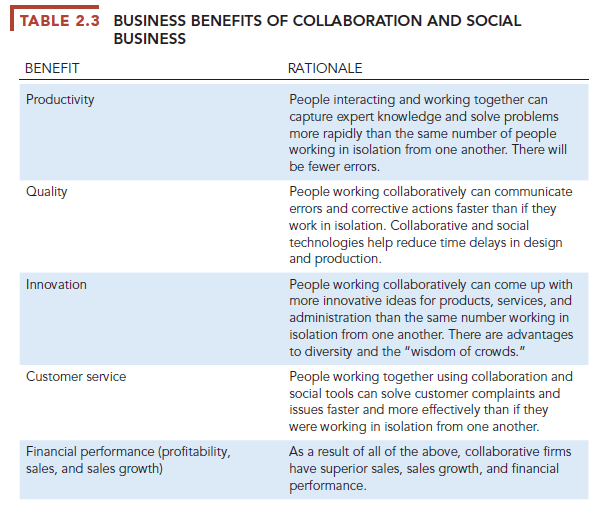

Much of the research on collaboration has been anecdotal, but there is a general belief among both business and academic communities that the more a business firm is “collaborative,” the more successful it will be, and that collaboration within and among firms is more essential than in the past. MIT Sloan Management Review’s research found that a focus on collaboration is central to how digitally advanced companies create business value and establish competitive advantage (Kiron, 2017). A global survey of business and information systems managers found that investments in collaboration technology produced organizational improvements that returned more than four times the amount of the investment, with the greatest benefits for sales, marketing, and research and development functions (Frost and Sullivan, 2009). McKinsey & Company consultants predict that social technologies used within and across enterprises could potentially raise the productivity of interaction workers by 20 to 25 percent (McKinsey Global Institute, 2012).

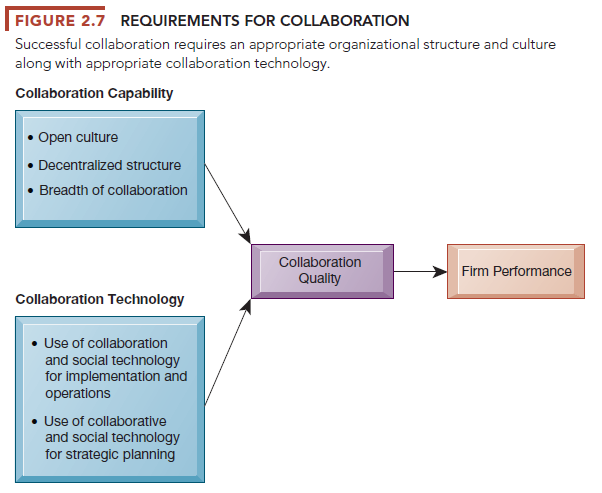

Table 2.3 summarizes some of the benefits of collaboration and social business that have been identified. Figure 2.7 graphically illustrates how collaboration is believed to affect business performance.

4. Building a Collaborative Culture and Business Processes

Collaboration won’t take place spontaneously in a business firm, especially in the absence of supportive culture or business processes. Business firms, especially large firms, had a reputation in the past for being “command and control” organizations where the top leaders thought up all the really important matters and then ordered lower-level employees to execute senior management plans. The job of middle management supposedly was to pass messages back and forth, up and down the hierarchy.

Command and control firms required lower-level employees to carry out orders without asking too many questions, with no responsibility to improve processes, and with no rewards for teamwork or team performance. If your work group needed help from another work group, that was something for the bosses to figure out. You never communicated horizontally, always vertically, so management could control the process. Together, the expectations of management and employees formed a culture, a set of assumptions about common goals and how people should behave. Many business firms still operate this way.

A collaborative business culture and business processes are very different. Senior managers are responsible for achieving results but rely on teams of employees to achieve and implement the results. Policies, products, designs, processes, and systems are much more dependent on teams at all levels of the organization to devise, to create, and to build. Teams are rewarded for their performance, and individuals are rewarded for their performance in a team. The function of middle managers is to build the teams, coordinate their work, and monitor their performance. The business culture and business processes are more “social.” In a collaborative culture, senior management establishes collaboration and teamwork as vital to the organization, and it actually implements collaboration for the senior ranks of the business as well.

5. Tools and Technologies for Collaboration and Social Business

A collaborative, team-oriented culture won’t produce benefits without information systems in place to enable collaboration and social business. Currently there are hundreds of tools designed to deal with the fact that, in order to succeed in our jobs, we are all much more dependent on one another, our fellow employees, customers, suppliers, and managers. Some of these tools are expensive, but others are available online for free (or with premium versions for a modest fee). Let’s look more closely at some of these tools.

5.1. E-mail and Instant Messaging (IM)

E-mail and instant messaging (including text messaging) have been major communication and collaboration tools for interaction jobs. Their software operates on computers, mobile phones, tablets, and other wireless devices and includes features for sharing files as well as transmitting messages. Many instant messaging systems allow users to engage in real-time conversations with multiple participants simultaneously. In recent years, e-mail use has declined, with messaging and social media becoming preferred channels of communication.

5.2. Wikis

Wikis are a type of website that makes it easy for users to contribute and edit text content and graphics without any knowledge of web page development or programming techniques. The most well-known wiki is Wikipedia, the largest collaboratively edited reference project in the world. It relies on volunteers, makes no money, and accepts no advertising.

Wikis are very useful tools for storing and sharing corporate knowledge and insights. Enterprise software vendor SAP AG has a wiki that acts as a base of information for people outside the company, such as customers and software developers who build programs that interact with SAP software. In the past, those people asked and sometimes answered questions in an informal way on SAP online forums, but that was an inefficient system, with people asking and answering the same questions over and over.

5.3. Virtual Worlds

Virtual worlds, such as Second Life, are online 3-D environments populated by “residents” who have built graphical representations of themselves known as avatars. Companies like IBM, Cisco, and Intel Corporations use the online world for meetings, interviews, guest speaker events, and employee training. Real-world people represented by avatars meet, interact, and exchange ideas at these virtual locations using gestures, chat box conversations, and voice communication.

5.4. Collaboration and Social Business Platforms

There are now suites of software products providing multifunction platforms for collaboration and social business among teams of employees who work together from many different locations. The most widely used are Internet-based audio conferencing and video conferencing systems, cloud collaboration services such as Google’s online services and tools, corporate collaboration systems such as Microsoft SharePoint and IBM Notes, and enterprise social networking tools such as Salesforce Chatter, Microsoft Yammer, Jive, Facebook Workplace, and IBM Connections.

Virtual Meeting Systems In an effort to reduce travel expenses and enable people in different locations to meet and collaborate, many companies, both large and small, are adopting videoconferencing and web conferencing technologies. Companies such as Heinz, GE, and PepsiCo are using virtual meeting systems for product briefings, training courses, and strategy sessions.

A videoconference allows individuals at two or more locations to communicate simultaneously through two-way video and audio transmissions. High-end videoconferencing systems feature telepresence technology, an integrated audio and visual environment that allows a person to give the appearance of being present at a remote location (see the Interactive Session on Technology). Free or low-cost Internet-based systems such as Skype group videoconferencing, Amazon Chime, and Zoom are of lower quality, but still useful for smaller companies. Apple’s FaceTime is useful for one-to-one videoconferencing. Some of these tools are available on mobile devices.

Companies of all sizes are finding web-based online meeting tools such as Cisco WebEx, Skype for Business, GoTo Meeting, and Adobe Connect especially helpful for training and sales presentations. These products enable participants to share documents and presentations in conjunction with audioconferencing and live video.

Cloud Collaboration Services Google offers many online tools and services, and some are suitable for collaboration. They include Google Drive, Google Docs, G Suites, and Google Sites. Most are free of charge.

Google Drive is a file storage and synchronization service for cloud storage, file sharing, and collaborative editing. Such web-based online file-sharing services allow users to upload files to secure online storage sites from which the files can be shared with others. Microsoft OneDrive and Dropbox are other leading cloud storage services. They feature both free and paid services, depending on the amount of storage space and administration required. Users are able to synchronize their files stored online with their local PCs and other kinds of devices, with options for making the files private or public and for sharing them with designated contacts.

Google Drive and Microsoft OneDrive are integrated with tools for document creation and sharing. OneDrive provides online storage for Microsoft Office documents and other files and works with Microsoft Office apps, both installed and on the web. It can share to Facebook as well. Google Drive is integrated with Google Docs, Sheets, and Slides, a suite of productivity applications that offer collaborative editing on documents, spreadsheets, and presentations. Google’s cloud-based productivity suite for businesses, called G Suite, also works with Google Drive. Google Sites allows users to quickly create online team-oriented sites where multiple people can collaborate and share files.

Microsoft SharePoint and IBM Notes Microsoft SharePoint is a browser-based collaboration and document management platform, combined with a powerful search engine, that is installed on corporate servers. SharePoint has a web-based interface and close integration with productivity tools such as Microsoft Office.

SharePoint software makes it possible for employees to share their documents and collaborate on projects using Office documents as the foundation.

SharePoint can be used to host internal websites that organize and store information in one central workspace to enable teams to coordinate work activities, collaborate on and publish documents, maintain task lists, implement workflows, and share information via wikis and blogs. Users are able to control versions of documents and document security. Because SharePoint stores and organizes information in one place, users can find relevant information quickly and efficiently while working closely together on tasks, projects, and documents. Enterprise search tools help locate people, expertise, and content. SharePoint now features social tools.

IBM Notes (formerly Lotus Notes) is a collaborative software system with capabilities for sharing calendars, e-mail, messaging, collective writing and editing, shared database access, and online meetings. Notes software installed on desktop or laptop computers obtains applications stored on an IBM Domino server. Notes is web-enabled and offers an application development environment so that users can build custom applications to suit their unique needs. Notes has also added capabilities for blogs, microblogs, wikis, online content aggregators, help desk systems, voice and video conferencing, and online meetings. IBM Notes promises high levels of security and reliability and the ability to retain control over sensitive corporate information.

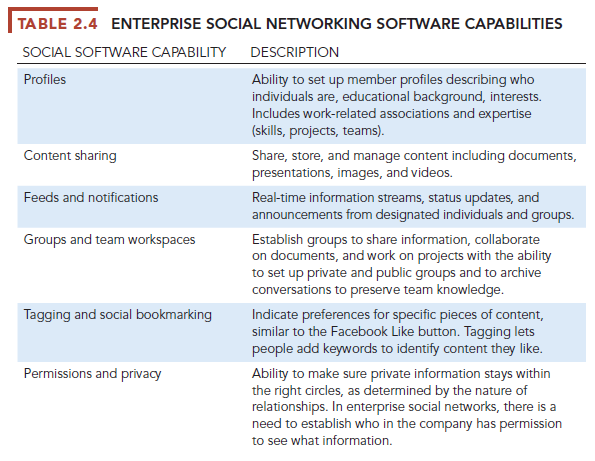

Enterprise Social Networking Tbols The tools we have just described include capabilities for supporting social business, but there are also more specialized social tools for this purpose, such as Salesforce Chatter, Microsoft Yammer, Jive, Face- book Workplace, and IBM Connections. Enterprise social networking tools create business value by connecting the members of an organization through profiles, updates, and notifications similar to Facebook features but tailored to internal corporate uses. Table 2.4 provides more detail about these internal social capabilities.

Although companies have benefited from enterprise social networking, internal social networking has not always been easy to implement. The chapterending case study addresses this topic.

6. Checklist for Managers: Evaluating and Selecting Collaboration and Social Software Tools

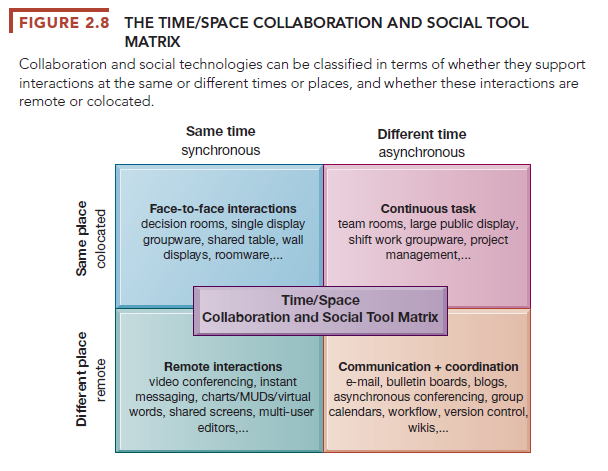

With so many collaboration and social business tools and services available, how do you choose the right collaboration technology for your firm? To answer this question, you need a framework for understanding just what problems these tools are designed to solve. One framework that has been helpful for us to talk about collaboration tools is the time/space collaboration and social tool matrix developed in the early 1990s by a number of collaborative work scholars (Figure 2.8).

The time/space matrix focuses on two dimensions of the collaboration problem: time and space. For instance, you need to collaborate with people in different time zones, and you cannot all meet at the same time. Midnight in New York is noon in Mumbai, so this makes it difficult to have a videoconference (the people in New York are too tired). Time is clearly an obstacle to collaboration on a global scale.

Place (location) also inhibits collaboration in large global or even national and regional firms. Assembling people for a physical meeting is made difficult by the physical dispersion of distributed firms (firms with more than one location), the cost of travel, and the time limitations of managers.

The collaboration and social technologies we have just described are ways of overcoming the limitations of time and space. Using this time/space framework will help you to choose the most appropriate collaboration and teamwork tools for your firm. Note that some tools are applicable in more than one time/ place scenario. For example, Internet collaboration suites such as IBM Notes have capabilities for both synchronous (instant messaging, meeting tools) and asynchronous (e-mail, wikis, document editing) interactions.

Here’s a “to-do” list to get started. If you follow these six steps, you should be led to investing in the correct collaboration software for your firm at a price you can afford and within your risk tolerance.

- What are the collaboration challenges facing the firm in terms of time and space? Locate your firm in the time/space matrix. Your firm can occupy more than one cell in the matrix. Different collaboration tools will be needed for each situation.

- Within each cell of the matrix where your firm faces challenges, exactly what kinds of solutions are available? Make a list of vendor products.

- Analyze each of the products in terms of its cost and benefits to your firm. Be sure to include the costs of training in your cost estimates and the costs of involving the information systems department, if needed.

- Identify the risks to security and vulnerability involved with each of the products. Is your firm willing to put proprietary information into the hands of external service providers over the Internet? Is your firm willing to expose its important operations to systems controlled by other firms? What are the financial risks facing your vendors? Will they be here in three to five years? What would be the cost of making a switch to another vendor in the event the vendor firm fails?

- Seek the help of potential users to identify implementation and training issues. Some of these tools are easier to use than others.

- Make your selection of candidate tools, and invite the vendors to make presentations.

Source: Laudon Kenneth C., Laudon Jane Price (2020), Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm, Pearson; 16th edition.

Hi! I’ve been reading your web site for a long time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Humble Texas! Just wanted to say keep up the good job!