Throwing the coin and wagering heads or tails is the simplest random process. If there are more than two possibilities, obviously, throwing the coin is useless. Then, we may resort to the method of picking paper strips with hidden numbers, this being suitable for any number including two. In the hope of reducing the subjective part and enhancing randomization, statisticians have devised a few more methods, often elaborate. Two such methods are outlined, using as examples the process of randomizing land plots for agriculture that we have dealt with earlier.

- Using a pack of cards. We have five varieties of rice to be tested. Number those as varieties 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5. We have four blocks, each with five plots, together making twenty plots. We take a pack of cards numbered one to one hundred (one hundred is divisible by five), shuffle thoroughly, and lay them in random order in a line. Take the first card; let us say it bears the number seventy-two; this number, when divided by five, leaves a remainder of two. Assign the first plot, starting from one end, with rice variety 2. Then, pick the second card, let us say this bears the number thirty-nine; this divided by five leaves a remainder of four. Assign the second plot with variety 4; and so on. When the remainder is zero, it corresponds to variety 5. If there are repetitions within a block (of five plots), discard that card, and go to the next. By this method, proceed until all twenty plots are assigned, each with a variety of rice. Suppose the number of varieties was six instead of five. Then, we would need to use ninety-six cards, not one hundred, as ninety-six is divisible by six.

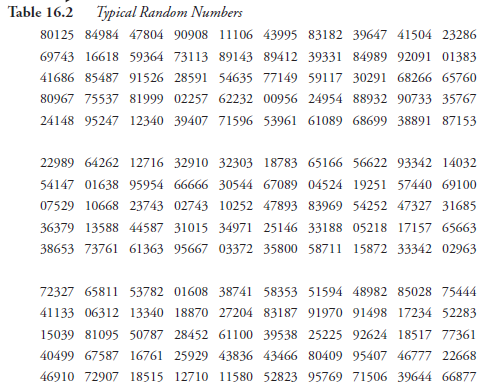

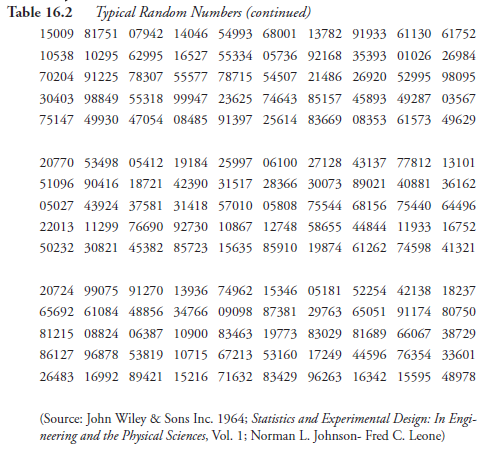

- Using tables of random numbers. Known as random digits or random permutations, such tables are available in print, attached as appendixes to many books on statistics; a typical one is shown in Table 16.2. In such a table, we may start anywhere, choose to go on any line, horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, and use each number instead of a numbered card, as in the previous method. If there is such a table with each number of four digits instead, we may choose the last two digits each time, or the first two, or the middle two, and so forth. If any number yields unwanted repetition, or is superfluous or unsuitable (example, four to be divided by five), we simply ignore it and go to the next number. Since randomization is the aim, freedom in using these tables is practically unlimited. The advantage of this method is that instead of a pack of numbered cards, and the need to shuffle and lay the cards in a random order, all we need is a printed sheet or to open a book to the page with such a table.

Though the previous two examples were mentioned in reference to randomizing the agriculture plots, needless to say, these methods can be adapted to many other contexts, the essence being to match members of one category at random with those of another.

Source: Srinagesh K (2005), The Principles of Experimental Research, Butterworth-Heinemann; 1st edition.

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

4 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021

5 Aug 2021