1. Current Debates About Affirmative Action

Affirmative action refers to government-mandated programs that focus on providing opportunities to women and members of minority groups who previously faced discrimina- tion. It is not the same thing as diversity, but affirmative action has facilitated greater re- cruitment, retention, and promotion of minorities and women. Affirmative action has made workplaces much more fair and equitable. However, research shows that full integra- tion of women and racial minorities into organizations is still nearly a decade away.141 De- spite affirmative action’s successes, salaries and promotion opportunities for women and minorities continue to lag behind those of white males.

Affirmative action was developed in response to conditions 40 years ago. Adult white males dominated the workforce, and economic conditions were stable and improving. Because of widespread prejudice and discrimination, legal and social coercion were neces- sary to allow women, people of color, immigrants, and other minorities to become part of the economic system.142

Affirmative action is highly controversial today. The economic and social environment has changed tremendously since the 1960s. “Minority” groups have become the majority in large U.S. cities. More than half of the U.S. workforce consists of women and minori- ties, and the economic climate changes rapidly as a result of globalization. Some mem- bers of nonprotected groups argue that affirmative action is no longer needed and that it leads to reverse discrimination. Even the intended beneficiaries of affirmative action pro- grams often disagree as to their value, and some believe these programs do more harm than good. One reason may be the stigma of incompetence that often is associated with affirmative action hires. One study found that both working managers and students consistently rated people portrayed as affirmative action hires as less competent and rec- ommended lower salary increases than for those not associated with affirmative action.143

In addition, people who perceive that they were hired because of affirmative action requirements may demonstrate negative self-perceptions and negative views of the orga- nization, which leads to lower performance and reinforces the opinions of others that they are less competent.144

Recent court decisions weakened affirmative action’s clout while still upholding its value. For example, the Supreme Court preserved affirmative action policies as a means of achieving diversity in universities but barred the use of point systems that might favor minority candidates.145 Other court decisions have also limited the use of certain affir- mative action practices for hiring and college admissions. In general, though, the courts support the continued use of affirmative action as a means of giving women and minor- ity groups equal access to opportuni-ties. In addition, according to a Gallup poll conducted to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling that declared school segregation unconstitutional, 57 percent of Americans support the continued use of affirmative action.146

1.1. THE GLASS CEILING

The glass ceiling is an invisible barrier that separates women and minorities from top management positions. They can look up through the ceiling and see top management, but prevailing attitudes and stereo- types are invisible obstacles to their own advancement.

In addition, women and minorities are often excluded from informal manager networks and often don’t get access to the type of general and line management experience that is required for moving to the top.147 Research suggests the existence of glass walls that serve as invisible barriers to important lateral movement within the organization. Glass walls, such as exclusion from manager networks, bar experience in areas such as line super- vision that would enable women and minorities to advance vertically.148

Evidence that the glass ceiling persists is the distribution of women and minorities, who are clustered at the bottom levels of the corporate hierarchy. Among minority groups, women have made the biggest strides in recent years, but they still represent only 15.7 per- cent of corporate officers in America’s 500 largest companies, up from 12.5 percent in 2000 and 8.7 percent in 1995.149 In 2006, only eight Fortune 500 companies had female CEOs. And both male and female African Americans and Hispanics continue to hold only a small percentage of all management positions in the United States.150

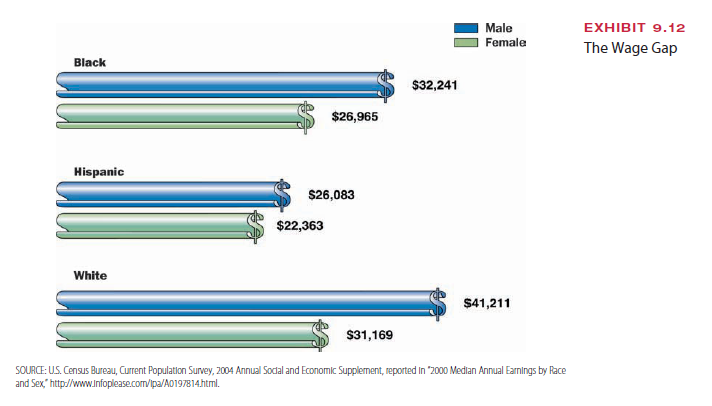

Women and minorities also make less money. As shown in Exhibit 9.12, black men earn about 22 percent less, white women 24 percent less, and Hispanic men 37 percent less than white males. Minority women fare even worse, with black women earning 35 percent less and Hispanic women 46 percent less than white males.151

Another sensitive issue related to the glass ceiling is homosexuals in the workplace. Many gay men and lesbians believe they will not be accepted as they are and risk losing their jobs or their chances for advancement. Gay employees of color are particularly hesi- tant to disclose their sexual orientation at work because by doing so they risk a double dose of discrimination.152 Although some examples of openly gay corporate leaders can be found, such as David Geffen, co-founder of DreamWorks SKG, and Ford Vice Chairman Allan D. Gilmour, most managers still believe staying in the closet is the only way they can succeed at work. Thus, gays and lesbians often fabricate heterosexual identities to keep their jobs or avoid running into the glass ceiling they see other employ- ees encounter.

1.2. THE OPT-OUT TREND

Many women are never hitting the glass ceiling because they choose to get off the fast track long before it comes into view. In recent years, an ongoing discussion concerns something referred to as the opt-out trend. In a recent survey of nearly 2,500 women and 653 men, 37 percent of highly qualified women report that they voluntarily left the workforce at some point in their careers, compared to only 24 percent of similarly qualified men.153

Quite a debate rages over the reasons for the larger number of women who drop out of mainstream careers. Opt-out proponents say women are deciding that corporate suc- cess isn’t worth the price in terms of reduced family and personal time, greater stress, and negative health effects.154 Women don’t want corporate power and status in the same way that men do, and clawing one’s way up the corporate ladder has become less appealing. For example, Marge Magner left her job as CEO of Citigroup’s Consumer Group after suffering both the death of her mother and a personal life-changing acci- dent in the same year. In evaluating her reasons, Magner said she realized that “life is about everything, not just the work.” For many women today, the high-pressure climb to the top is just not worth it. Some are opting out to be stay-at-home moms, while others want to continue working but just not in the kind of fast-paced, competitive, aggressive environment that exists in most corporations. Some researchers who study the opt-out trend say that most women just don’t want to work as hard and competi- tively as most men want to work.155

Critics, however, argue that this view is just another way to blame women themselves for the dearth of female managers at higher levels.156 Vanessa Castagna, for example, left JCPenney after decades with the company not because she wanted more family or per- sonal time but because she kept getting passed over for top jobs.157 Although some women are voluntarily leaving the fast track, many more genuinely want to move up the corporate ladder but find their paths blocked. Fifty-five percent of executive women surveyed by Catalyst said they aspire to senior leadership levels.158 In addition, a survey of 103 women voluntarily leaving executive jobs in Fortune 1000 companies found that corporate culture was cited as the number 1 reason for leaving.159 The greatest disadvan- tages of women leaders stem largely from prejudicial attitudes and a heavily male-oriented corporate culture.160 Some years ago, when Procter & Gamble asked the female execu- tives it considered “regretted losses” (that is, high performers the company wanted to retain) why they left their jobs, the most common answer was that they didn’t feel valued by the company.161 Top-level corporate culture evolves around white, heterosexual, American males, who tend to hire and promote people who look, act, and think like them. Compatibility in thought and behavior plays an important role at higher levels of organizations. For example, among women who managed to break through the glass ceiling, fully 96 percent said adapting to a predominantly white male culture was neces- sary for their success.162

1.3. THE FEMALE ADVANTAGE

Some people think women might actually be better managers, partly because of a more collaborative, less hierarchical, relationship-oriented approach that is in tune with today’s global and multicultural environment.163 As attitudes and values change with changing generations, the qualities women seem to naturally possess may lead to a gradual role rever- sal in organizations. For example, a stunning gender reversal is taking place in U.S. educa- tion, with girls taking over almost every leadership role from kindergarten to graduate school. In addition, women of all races and ethnic groups are outpacing men in earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees. In 2005, women made up 57 percent of undergraduate college students. The gender gap in some states is even wider, with Maine reporting the greatest gap, with 154 women for every 100 men in the state’s colleges and universities.164

Among 25- to 29-year-olds, 32 percent of women have college degrees, compared to 27 percent of men. Women are rapidly closing the M.D. and Ph.D. gap, and they make up about half of all U.S. law students, half of all undergraduate business majors, and about 30 percent of MBA candidates. Overall, women’s participation in both the labor force and civic affairs steadily increased since the mid-1950s, while men’s participation has slowly but steadily declined.165

According to James Gabarino, an author and professor of human development at Cornell University, women are “better able to deliver in terms of what modern society requires of people—paying attention, abiding by rules, being verbally competent, and dealing with interpersonal relationships in offices.”166 His observation is supported by the fact that female managers are typically rated higher by subordinates on interpersonal skills as well as on factors such as task behavior, communication, ability to motivate oth- ers, and goal accomplishment.167 Recent research found a correlation between balanced gender composition in companies (that is, roughly equal male and female representation) and higher organizational performance. Moreover, a study by Catalyst indicates that organizations with the highest percentage of women in top management financially out- perform, by about 35 percent, those with the lowest percentage of women in higher-level jobs.168 It seems that women should be marching right to the top of the corporate hierar- chy, but prevailing attitudes, values, and perceptions in organizations create barriers and a glass ceiling.

2. Current Responses to Diversity

Today’s companies are searching for inclusive practices that go well beyond affirmative action to confront the obstacles that prevent women and minorities from advancing to senior management positions. Procter & Gamble, for example, dramatically improved its retention of women and increased the number who moved into senior level positions by offering time-management training and greater flexibility that enabled more women to accept career-oriented line management jobs.169 When the Boston-based law firm Mintz Levin Cohn Ferris Glovsky & Popeo decided to build an employment law practice in Washington, the partners determined to create a diverse, inclusive environment by hir- ing many minority lawyers for senior positions from the start. The goal is to create a “critical mass” of people who can serve as role models and mentors for younger minority lawyers who typically find it difficult to move up the ranks and become partners in large law firms.170

To prepare for and respond to an increasingly diverse business climate, managers in most companies are also expanding the organization’s emphasis on diversity beyond race and gender to consider such factors as ethnicity, age, physical ability, religion, and sexual orientation. Generational diversity is a key concern for managers in many of today’s companies, with four generations working side-by-side, each with a different mind-set and different expectations. “In my career, I was trained not to start a meeting without an agenda,” says 55-year-old manager J. Robert Carr. “Gen Yers make up the agenda as they go along.”171

After managers create and define a vision for a diverse workplace, they can analyze and assess the current culture and systems within the organization. Actions to develop an inclu- sive workplace that values and respects all people include three major steps: (1) building a corporate culture that values diversity; (2) changing structures, policies, and systems to support diversity; and (3) providing diversity awareness training.

3. Defining New Relationships in Organizations

One outcome of diversity is an increased incidence of close personal relationships in the workplace, which can have both positive and negative results for employees as well as the organization. Two issues of concern are emotional intimacy and sexual harassment.

3.1. EMOTIONAL INTIMACY

Close emotional relationships, particularly between men and women, often have been dis- couraged in companies for fear that they would disrupt the balance of power and threaten organizational stability.172 This opinion grew out of the assumption that organizations are designed for rationality and efficiency, which were best achieved in a nonemotional environment.

However, a recent study of friendships in organizations sheds interesting light on this issue.173 Managers and workers responded to a survey about emotionally intimate relationships with both male and female co-workers. Many men and women reported having close relationships with an opposite-sex co-worker. Called nonromantic love rela- tionships, the friendships resulted in trust, respect, constructive feedback, and support in achieving work goals. Intimate friendships did not necessarily become romantic, and they affected each person’s job and career in a positive way. Rather than causing problems, non- romantic love relationships, according to the study, affected work teams in a positive man- ner because conflict was reduced. Men reported somewhat greater benefit than women from these relationships, perhaps because the men had fewer close relationships outside the workplace upon which to depend.

However, when such relationships do become romantic or sexual in nature, real problems can result. Romances that require the most attention from managers are those that arise between a supervisor and a subordinate. These relationships often lead to morale problems among other staff members, complaints of favoritism, and ques- tions about the supervisor’s intentions or judgment. Harry Stonecipher was ousted as CEO of Boeing Corporation in 2005 after the board learned of an extramarital affair with a female executive. However, office romances in general are tolerated far more today than in the past. Some companies, including Xerox and IBM, have formal policies that allow romantic relationships between employees as long as neither party directly reports to the other. Surveys show that approximately 25 percent of sexual harassment policies now include guidelines about office relationships, and 70 percent of companies surveyed have policies prohibiting romantic relationships between a superior and a subordinate.174

3.2. SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Although psychological closeness between men and women in the workplace may be a positive experience, sexual harassment is not. Sexual harassment is illegal. As a form of sexual discrimination, sexual harassment in the workplace is a violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Sexual harassment in the classroom is a violation of Title VIII of the Education Amendment of 1972. The following list categorizes various forms of sexual harassment as defined by one university:

- Generalized. This form involves sexual remarks and actions that are not intended to lead to sexual activity but that are directed toward a co-worker based solely on gender and reflect on the entire group.

- Inappropriate/offensive. Though not sexually threatening, it causes discomfort in a co- worker, whose reaction in avoiding the harasser may limit his or her freedom and ability to function in the workplace.

- Solicitation with promise of reward. This action treads a fine line as an attempt to “pur- chase” sex, with the potential for criminal prosecution.

- Coercion with threat of punishment. The harasser coerces a co-worker into sexual activity by using the threat of power (through recommendations, grades, promotions, and so on) to jeopardize the victim’s career.

- Sexual crimes and misdemeanors. The highest level of sexual harassment, these acts would, if reported to the police, be considered felony crimes and misdemeanors.175

Statistics in Canada indicate that between 40 and 70 percent of women and about 5 percent of men have been sexually harassed at work.176 The situation in the United States is just as dire. Over a recent 10-year period, the EEOC shows a 150 percent increase in the number of sexual harassment cases filed annually.177 About 10 percent of those were filed by males. The Supreme Court held that same-sex harassment as well as harassment of men by female co-workers is just as illegal as the harassment of women by men. In the suit that prompted the Court’s decision, a male oil-rig worker claimed he was singled out by other members of the all-male crew for crude sex play, unwanted touching, and threats of rape.178

A growing number of men are urging recognition that sexual harassment is not just a woman’s problem.179

Because the corporate world is dominated by a male culture, however, sexual harassment affects women to a much greater extent. Companies such as Dow Chemical, Xerox, and The New York Times have been swift to fire employees for circulating pornographic images, surfing pornographic websites, or sending offensive e-mails.180

4. Global Diversity

Globalization is a reality for today’s companies. As stated in a report from the Hudson Institute, Workforce 2020, “The rest of the world matters to a degree that it never did in the past.”181 For example, Google, which employs about 4,000 people worldwide, has seen a tremendous increase in the number of immigrants working in its U.S. headquarters. This realization prompted leaders to take a new approach to the company cafeteria, as described in this chapter’s Benchmarking box.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Hello.This post was really interesting, especially because I was looking for thoughts on this topic last couple of days.