The organizing process leads to the creation of organization structure, which defines how tasks are divided and resources deployed. Organization structure is defined as (1) the set of formal tasks assigned to individuals and departments; (2) formal reporting relation- ships, including lines of authority, decision responsibility, number of hierarchical levels, and span of managers’ control; and (3) the design of systems to ensure effective coordina- tion of employees across departments.4

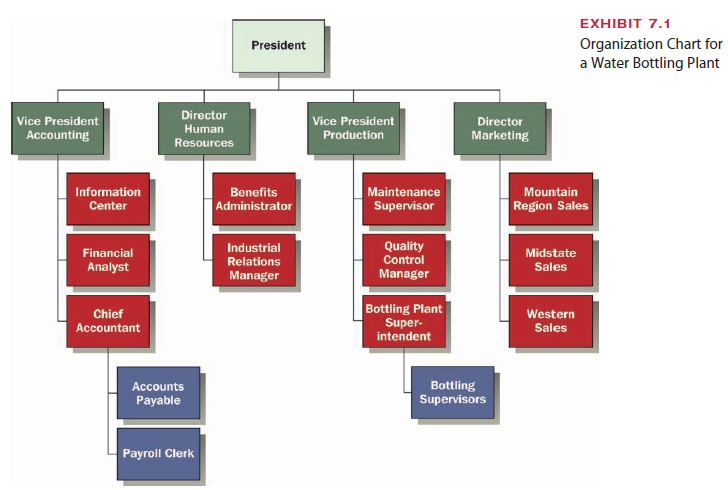

The set of formal tasks and formal reporting relationships provides a framework for vertical control of the organization. The characteristics of vertical structure are portrayed in the organization chart, which is the visual representation of an organization’s structure.

A sample organization chart for a water bottling plant is illustrated in Exhibit 7.1. The plant has four major departments—Accounting, Human Resources, Production, and Marketing. The organization chart delineates the chain of command, indicates departmental tasks and how they fit together, and provides order and logic for the organization. Every employee has an appointed task, line of authority, and decision responsibility. The following sections discuss several important features of vertical structure in more detail.

1. WORK SPECIALIZATION

Organizations perform a wide variety of tasks. A fundamental principle is that work can be performed more efficiently if employees are allowed to specialize.5 Work specialization, sometimes called division of labor, is the degree to which organizational tasks are subdi- vided into separate jobs. Work specialization in Exhibit 7.1 is illustrated by the separation of production tasks into bottling, quality control, and maintenance. Employees within each department perform only the tasks relevant to their specialized function. When work spe- cialization is extensive, employees specialize in a single task. Jobs tend to be small, but they can be performed efficiently. Work specialization is readily visible on an automobile as- sembly line where each employee performs the same task over and over again. It would not be efficient to have a single employee build the entire automobile or even perform a large number of unrelated jobs.

Despite the apparent advantages of specialization, many organizations are moving away from this principle. With too much specialization, employees are isolated and do only a single, boring job. Many companies are enlarging jobs to provide greater challenges or as- signing teams so that employees can rotate among the several jobs performed by the team. One company that has followed work specialization, though, is Kate Spade, as described in the Spotlight on Skills box.

2. CHAIN OF COMMAND

The chain of command is an unbroken line of authority that links all persons in an orga- nization and shows who reports to whom. It is associated with two underlying principles. Unity of command means that each employee is held accountable to only one supervisor. The scalar principle refers to a clearly defined line of authority in the organization that in- cludes all employees. Authority and responsibility for different tasks should be distinct. All persons in the organization should know to whom they report as well as the successive management levels all the way to the top. In Exhibit 7.1 shown earlier, the payroll clerk re- ports to the chief accountant, who in turn reports to the vice president, who in turn reports to the company president.

3. AUTHORITY, RESPONSIBILITY, AND DELEGATION

The chain of command illustrates the authority structure of the organization. Authority is the formal and legitimate right of a manager to make decisions, issue orders, and allocate resources to achieve organizationally desired outcomes. Authority is distinguished by three characteristics:

- Authority is vested in organizational positions, not people. Managers have authority because of the positions they hold, and other people in the same positions would have the same authority.

- Authority is accepted by subordinates. Although authority flows top-down through the organization’s hierarchy, subordinates comply because they believe that managers have a legitimate right to issue orders. The acceptance theory of authority argues that a manager has authority only if subordinates choose to accept his or her commands. If subordinates refuse to obey because the order is outside their zone of acceptance, a manager’s authority disappears.7

- Authority flows down the vertical hierarchy. Positions at the top of the hierarchy are vested with more formal authority than are positions at the bottom.

Responsibility is the flip side of the authority coin. Responsibility is the duty to per- form the task or activity as assigned. Typically, managers are assigned authority commen- surate with responsibility. When managers have responsibility for task outcomes but little authority, the job is possible but difficult. They rely on persuasion and luck. When manag- ers have authority exceeding responsibility, they may become tyrants, using authority toward frivolous outcomes.8

Accountability is the mechanism through which authority and responsibility are brought into alignment. Accountability means that the people with authority and responsibility are subject to reporting and justifying task outcomes to those above them in the chain of command.9 For organizations to function well, everyone needs to know what they are ac- countable for and accept the responsibility and authority for performing it. Accountability can be built into the organization structure. For example, at Whirlpool, incentive programs tailored to different hierarchical levels provide strict accountability. Performance of all managers is monitored, and bonus payments are tied to successful outcomes. Another example comes from Caterpillar Inc., which got hammered by new competition in the mid-1980s and reorganized to build in accountability.

Some top managers at Caterpillar had trouble letting go of authority and responsibility in the new structure because they were used to calling all the shots. Another important concept related to authority is delegation.11 Delegation is the process managers use to transfer authority and responsibility to positions below them in the hierarchy. Most orga- nizations today encourage managers to delegate authority to the lowest possible level to provide maximum flexibility to meet customer needs and adapt to the environment. How- ever, as at Caterpillar, many managers find delegation difficult.

Line Authority and Staff Authority. An important distinction in many organizations is between line authority and staff authority, reflecting whether managers work in line departments or staff departments in the organization’s structure. Line depart- ments perform tasks that reflect the organization’s primary goal and mission. In a software company, line departments make and sell the product. In an Internet-based company, line departments develop and manage online offerings and sales. Staff departments include all those that provide specialized skills in support of line departments. Staff departments have an advisory relationship with line de-partments and typically include market- ing, labor relations, research, account- ing, and human resources.

Line authority means that people in management positions have formal au- thority to direct and control immediate subordinates. Staff authority is nar- rower and includes the right to advise, recommend, and counsel in the staff spe- cialists’ area of expertise. Staff authority is a communication relationship; staff spe- cialists advise managers in technical areas. For example, the finance department of a manufacturing firm would have staff authority to coordinate with line depart- ments about which accounting forms to use to facilitate equipment purchases and standardize payroll services.

4. SPAN OF MANAGEMENT

The span of management is the number of employees reporting to a supervisor. Sometimes called the span of control, this characteristic of structure determines how closely a supervisor can monitor subordinates. Traditional views of organization design recommended a span of management of about seven subordinates per manager. However, many lean or-ganizations today have spans of management as high as 30, 40, and even higher. For ex- ample, at Consolidated Diesel’s team-based engine assembly plant, the span of manage- ment is 100.12 Research over the past 40 or so years shows that span of management varies widely and that several factors influence the span.13 Generally, when supervisors must be closely involved with subordinates, the span should be small, and when supervisors need little involvement with subordinates, it can be large. The following factors are associated with less supervisor involvement and thus larger spans of control:

- Work performed by subordinates is stable and routine.

- Subordinates perform similar work tasks.

- Subordinates are concentrated in a single location.

- Subordinates are highly trained and need little direction in performing tasks.

- Rules and procedures defining task activities are available.

- Support systems and personnel are available for the manager.

- Little time is required in nonsupervisory activities such as coordination with other departments or planning.

- Managers’ personal preferences and styles favor a large span.

The average span of control used in an organization determines whether the structure is tall or flat. A tall structure has an overall narrow span and more hierarchical levels. A flat structure has a wide span, is horizontally dispersed, and has fewer hierarchical levels.

Having too many hierarchical levels and narrow spans of control is a common structural problem for organizations. The result may be routine decisions that are made too high in the organization, which pulls higher-level executives away from important long-range stra- tegic issues. It also limits the creativity and innovativeness of lower-level managers in solv- ing problems.14 The trend in recent years has been toward wider spans of control as a way to facilitate delegation.15 One study of 300 large U.S. corporations found that the average number of division heads reporting directly to the CEO tripled between 1986 and 1999.16

Exhibit 7.2 illustrates how an international metals company was reorganized. The multi- level set of managers shown in panel a was replaced with 10 operating managers and 9 staff specialists reporting directly to the CEO, as shown in panel b. The CEO welcomed this wide span of 19 management subordinates because it fit his style, his management team was top quality and needed little supervision, and they were all located on the same floor of an office building.

5. CENTRALIZATION AND DECENTRALIZATION

Centralization and decentralization pertain to the hierarchical level at which decisions are made. Centralization means that decision authority is located near the top of the organi- zation. With decentralization, decision authority is pushed downward to lower organi- zation levels. Organizations may have to experiment to find the correct hierarchical level at which to make decisions.

In the United States and Canada, the trend over the past 30 years has been toward greater decentralization of organizations. Decentralization is believed to relieve the burden on top managers, make greater use of employees’ skills and abilities, ensure that decisions are made close to the action by well-informed people, and permit more rapid response to external changes.

However, this trend does not mean that every organization should decentralize all deci- sions. Managers should diagnose the organizational situation and select the decision- making level that will best meet the organization’s needs. Factors that typically influence centralization versus decentralization are as follows:

- Greater change and uncertainty in the environment are usually associated with decen- tralization. A good example of how decentralization can help cope with rapid change and uncertainty occurred following Hurricane Katrina. Recall from the Chapter 1 opening example how Mississippi Power restored power in just 12 days thanks largely to a decentralized management system that empowered people at the electrical substations to make rapid on-the-spot decisions. Simi-larly, decentralized decision making at UPS enabled trucks to keep running on time in New York after the September 2001 terrorist attacks.17 With the world rapidly changing, you could expect information management to be decentral- ized, as it is in Wikipedia’s model, described in the Benchmarking box.

- The amount of centralization or decentralization should fit the firm’s strategy. For ex- ample, Johnson & Johnson gives almost complete authority to its 180 operating companies to develop and market their own products. Decentralization fits the cor- porate strategy of empowerment that gets each division close to customers so it can speedily adapt to their needs.18 Taking the opposite approach, Procter & Gamble recentralized some of its operations to take a more focused approach and leverage the giant company’s capabilities across business units.19

- In times of crisis or risk of company failure, authority may be centralized at the top. When Honda could not get agreement among divisions about new car models, President Nobuhiko Kawamoto made the decision himself.20

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

Good day very nice web site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I will bookmark your site and take the feeds additionally…I am glad to search out numerous helpful information here in the publish, we want work out extra techniques on this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .