In recent years, most organizations have incorporated the Internet as part of their IT strategy.99 The Internet is a global collection of computer networks linked together for the exchange of data and information. The Internet became accessible as a public information and communications tool after Tim Berners-Lee, a researcher at CERN (Centre Européan pour la Recherche Nucléaire) in Geneva, Switzerland, designed software for the original World Wide Web (WWW), a user-friendly interface that today allows people to easily communicate with each other and with the Internet via a set of central servers.100

Both business and nonprofit organizations quickly realized the poten- tial of the Internet for expanding their operations globally, improving business processes, reaching new customers, and making the most of their resources. Exhibit 6.10 shows the opening Web page for IKEA, a Swedish furniture retailer with more than 200 stores around the world and a thriving catalog and Internet business.

E-business has begun to flourish. E-business can be defined as any business that takes place by digital processes over a computer network rather than in physical space. Most commonly today, it refers to electronic linkages over the Internet with customers, partners, suppliers, employ- ees, or other key constituents. E-commerce is a more limited term that refers specifically to business exchanges or transactions that occur electronically.

Some organizations are set up as e-businesses that are run completely over the Internet, such as eBay, Amazon.com, Expedia, and Yahoo!. These companies would not exist with- out the Internet. However, most traditional, established organizations, including General Electric, the City of Madison, Wisconsin; Target stores; and the U.S. Postal Service, also make extensive use of the Internet, and we will focus on these types of organizations in the remainder of this section. The goal of e-business for established organizations is to digi- talize as much of the business as possible to make the organization more efficient and ef- fective. Companies are using the Internet and the Web for everything from filing expense reports and calculating daily sales to connecting directly with suppliers for the exchange of information and ordering of parts.101 Indie rock band String Cheese Incident has used the Internet to create a highly profitable venture.

First, each organization operates an intranet, an internal communications system that uses the technology and standards of the Internet but is accessible only to people within the company. The next component is a system that allows the separate companies to share data and information. Two options are an electronic data interchange network or an extranet. Electronic data interchange (EDI) networks link the computer systems of buyers and sellers to allow the transmission of structured data primarily for ordering, distribution, and payables and receivables.102 An extranet is an external communications system that uses the Internet and is shared by two or more organizations. With an extranet, each organization moves certain data outside of its private intranet, but makes the data available only to the other companies sharing the extranet. The final piece of the overall system is the Internet, which is accessible to the general public. Organizations make some information available to the public through their Web sites, which may include products or services offered for sale. For example, at IKEA’s Web site, consumers can chat with an automated online assistant, use room planning tools for interior design, and order furniture and other products.

1. E-BUSINESS STRATEGIES

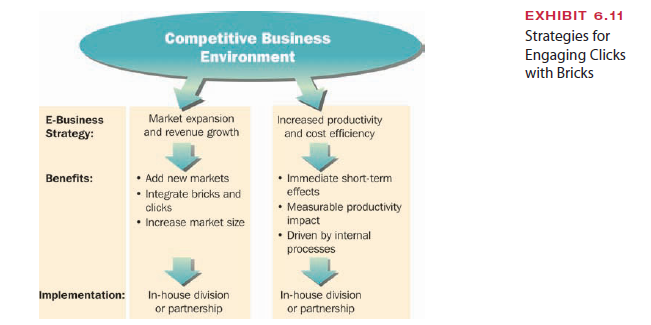

The first step toward a successful e-business is for managers to determine why they need such a business to begin with.103 Failure to align the e-business initiative with corporate strategy can lead to e-business failure. Two basic strategic approaches for traditional orga- nizations setting up an Internet operation are illustrated in Exhibit 6.11. Some companies embrace e-business primarily to expand into new markets and reach new customers. Others use e-business as a route to increased productivity and cost efficiency. As shown in the exhibit, these strategies are implemented either by setting up an in-house Internet division or by partnering with other organizations to handle online activities.

Market Expansion. An Internet division allows a company to establish direct links to customers and expand into new markets. The organization can provide access around the clock to a worldwide market and thus reach new customers. ESPN.com, for example, is the biggest Internet draw for sports, attracting a devoted audience of 18- to 34-year-old men, which is an audience that is less and less interested in traditional television. The site’s ESPN360, a customizable high-speed service, offers super-sharp video clips of everything from SportsCenter to poker tournaments, as well as behind-the-scenes coverage. To reach young viewers, other television networks, including Comedy Central; E. W. Scripps Net- works, which owns HGTV and the Food Network; CBS Broadcasting; and NBC Universal, are also launching high-speed broadband channels to deliver short videos, pilots of new shows, or abbreviated and behind-the-scenes looks.104 Print media organizations use Web sites to reach new customers, as well. Radar magazine is taking an innovative approach by launching a Web site to build a market before publishing the magazine itself.

It remains to be seen whether Radar will succeed in any form—print or online. Efforts have just begun to build a market for the new publication. For established firms, the market expansion strategy is competitively sustainable because the e-business division works in conjunction with a conventional bricks-and-mortar company. For example, The Finish

Line, a retailer of athletic clothing, footwear, and accessories, sells products online but also uses the Web site as a way to drive more traffic into its stores.106

Productivity and Efficiency. With this approach, the e-business initiative is seen primarily as a way to improve the bottom line by increasing productivity and cutting costs. An automaker, for example, might use e-business to reduce the cost of ordering and tracking parts and supplies and to implement just-in-time manufacturing. GM has imple- mented wireless Internet technology to increase productivity in 90 of its plants, where Wi-Fi devices are mounted on forklifts and used by assembly workers to track the move- ment of engine parts and car seats tagged with tiny chips that emit electronic signals.107 At Nibco, a manufacturer of piping products, 12 plants and distribution centers automatically share data on inventory and orders, resulting in about 70 percent of orders being auto- mated. The technology has enabled Nibco to trim its inventory by 13 percent, as well as re- spond more quickly to changes in orders from customers.108

Several studies attest to real and significant gains in productivity from e-business, and productivity gains from U.S. businesses were projected to reach $450 billion by 2005.109

Even the smallest companies can realize gains. Rather than purchasing parts from a local supplier at premium rates, a small firm can access a worldwide market and find the best price, or negotiate better terms with the local supplier.110 Service firms and government agencies can benefit too. New York City became the first city to use the Internet to settle personal injury claims more efficiently. Using NYC Comptroller’s Cybersettle Service, lawyers submit blind offers until a match is hit. If an agreement can’t be reached, the parties go back to face-to-face negotiations. The city saved $17 million in less than 2 years by settling 1,137 out of 7,000 claims online, and reduced settlement times from 4 years to 9 months.111

2. IMPLEMENTING E-BUSINESS STRATEGIES

When traditional organizations such as Nibco, CBS Broadcasting, or General Motors Corporation want to establish an Internet division, managers have to decide how best to integrate bricks and clicks—that is, how to blend their traditional operations with an Internet initiative.112 One approach is to set up an in-house division. This approach offers tight integration between the online business and the organization’s traditional operation.

Managers create a separate department or unit within the company that functions within the structure and guidance of the traditional organization. This approach gives the new division several advantages by piggybacking on the established company, including brand recognition, purchasing leverage with suppliers, shared customer information, and market- ing opportunities. Office Depot, for example, launched an online unit for market expan- sion as a tightly integrated in-house part of its overall operation. Managers and employees within the company are assigned to the unit to handle Web site maintenance, product of- ferings, order fulfillment, customer service, and other aspects of the online business.113

A second approach is through partnerships, such as joint ventures or alliances. Safeway partnered with the British supermarket chain Tesco, described in the previous chapter, to establish its online grocery business in the United States. Safeway first tried to go it alone but found that it needed the expertise of an established online player with a proven business model.114 In many cases, a traditional company will partner with an established Internet firm to reach a broader customer base or to handle activities such as customer service, order fulfillment, and Web site maintenance. Companies such as Linens ’n Things, Timberland, and Reebok partner with GSI Commerce, which stores goods, takes orders, and then picks, packs, and ships orders directly to customers. The bricks-and-mortar companies get the expertise and services of a world-class Internet business without having to hire more people with IT expertise and build the capabilities themselves.115

3. GOING INTERNATIONAL

When businesses were first rushing to set up Web sites, managers envisioned easily doing business all over the world. Soon, though, they awakened to the reality that national bound- aries matter just as much as they ever did. The global e-market can’t be approached as if it were one homogeneous piece.116 Organizations that want to succeed with international e-business are tailoring their Web sites to address differences in language, regulations, pay- ment systems, and consumer preferences in different parts of the world. For example, Yahoo!, Amazon, Dell, Walt Disney, and the National Football League have all set up country-specific sites in the local language. Washingtonpost.com gives its news a broader global flavor during the overnight hours when international readers frequent the site. eBay is struggling with currency issues, as it has alienated many potential users in other countries by quoting prices only in U.S. dollars. And companies with online stores are finding that they may need to offer a different product mix and discounts tailored to local preferences. The Internet is a powerful way to reach customers and partners around the world, and managers are learning to address the cross-national challenges that come with serving a worldwide market.

4. E-MARKETPLACES

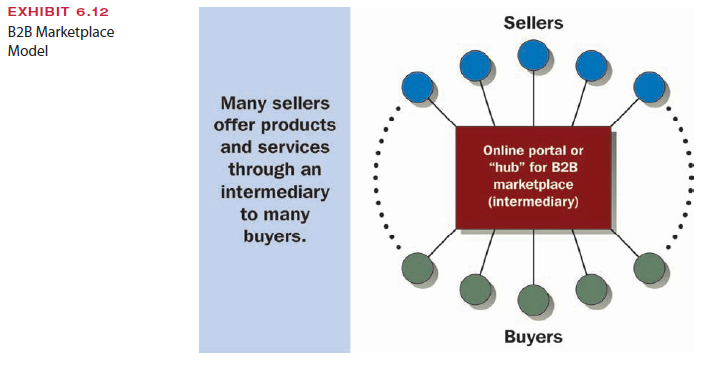

The biggest boom in e-commerce has been in business-to-business (B2B) transactions, or buying and selling between companies. B2B transactions are at $2.4 trillion and growing, according to Forrester Research Inc.117 One significant trend is the development of B2B marketplaces, in which an intermediary sets up an electronic marketplace where buyers and sellers meet, acting as a hub for B2B commerce. Exhibit 6.12 illustrates a B2B market- place, where many different sellers offer products and services to many different buyers through a hub, or online portal. Conducting business through a Web marketplace can mean lower transaction costs, more favorable negotiations, and productivity gains for both buyers and sellers. For example, defense contractor United Technologies buys around $450 million worth of metals, motors, and other products annually via an e-marketplace and gets prices about 15 percent less than what it once paid.118 Whirlpool uses Rearden Commerce, an online marketplace that is the world’s largest hub for services, to book travel arrangements, make restaurant reservations for managers, schedule shipping, and arrange other services. Within the first two months of using the system, shipping department em- ployees saved 10 percent and cut the time spent arranging for shipping by 52 percent.119

eBay, which started out as a marketplace primarily for consumers, has also expanded into B2B commerce. Reliable Tools, Inc., a machine tool shop, tried listing a few items on eBay in late 1998, including items such as a $7,000, 2,300-pound milling machine. The items “sold like ice cream in August,” and sales on eBay now make up about

75 percent of Reliable’s overall business. Pioneers such as Reliable spurred eBay to set up an industrial products marketplace, which is now on track to top $500 million in annual gross sales.120 The success of eBay has created an entirely new kind of mar- ketplace, where both individuals and businesses are buying and selling billions of dollars worth of goods a year. A Canadian organization, Mediagrif Interactive Technologies, is giving eBay a run for its money in the B2B marketplace. Mediagrif focuses its efforts entirely on B2B exchanges in markets such as used computer parts, routers and switches, automotive parts, medical equipment, and other areas.121

In addition to open, public B2B marketplaces such as eBay, Mediagrif, and AutoTradeCenter, where dealers buy about 100,000 used cars a year, some companies set up private marketplaces to link with a specially invited group of suppliers and partners.122 For example, General Motors spends billions a year on public market- places, but it also operates its own private marketplace, GMSupplyPower, to share proprietary information with thousands of its parts suppliers. E-marketplaces can bring efficiencies to many operations, but some companies find that they don’t offer the personal touch their type of business needs.

5. CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT

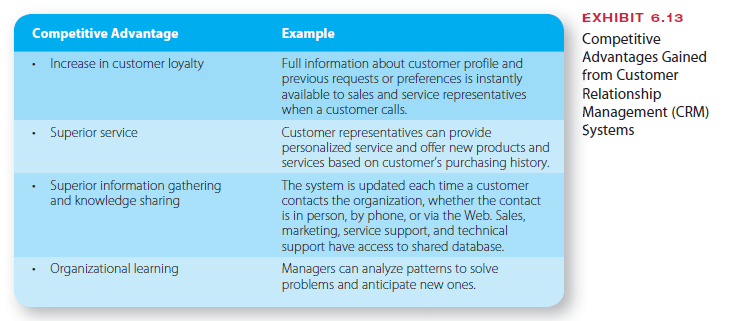

In addition to better internal information management and information sharing with sup- pliers and other organizations, companies are using e-business solutions to build stronger customer relationships. One approach is customer relationship management (CRM) systems that help companies track potential customers, follow customers’ interactions with the firm, and allow employees to call up a customer’s past sales and service records, outstanding orders, or unresolved problems.123 According to a 2005 study by Gartner Group, 60 percent of mid-sized businesses had plans to adopt or expand their CRM usage, while only 2 percent of surveyed companies had no plans for using this technology.124

Today, CRM tools are evolving to provide “collaborative customer experiences.”125

Whereas the traditional CRM model gives the organization insight into customers, the new approach provides for a two-way relationship that also gives customers transparency into company thinking. This means that, rather than having employees provide what they think customers want and need, employees and customers will jointly craft the customer experience, with the customer, rather than the company, defining what value means.

Increasingly, what distinguishes an organization from its competitors are its knowledge resources, such as product ideas and the ability to identify and find solutions to customers’ problems. Exhibit 6.13 lists examples of how CRM and other IT can shorten the distance between customers and the organization, contributing to organizational success through cus- tomer loyalty, superior service, better information gathering, and organizational learning.

6. TURNING DATA AND INFORMATION INTO KNOWLEDGE

The Internet also plays a key role in the recent emphasis managers are putting on knowl- edge management, the efforts to systematically gather knowledge, make it widely available throughout the organization, and foster a culture of learning. Some researchers believe that intellectual capital will soon be the primary way in which businesses measure their value.126

Therefore, managers see knowledge as an important resource to manage, just as they manage cash flow, raw materials, and other resources. An effective knowledge management system may incorporate a variety of technologies, supported by leadership that values learning, an organizational structure that supports communication and information sharing, and pro- cesses for managing change.127 Two specific technologies that facilitate knowledge manage- ment are business intelligence software and corporate intranets or networks. The use of new business intelligence software helps organizations make sense out of huge amounts of data.

These programs combine related pieces of information to create knowledge. Knowledge that can be codified, written down, and contained in databases is referred to as explicit knowledge. However, much organizational knowledge is unstructured and resides in people’s heads. This tacit knowledge cannot be captured in a database, making it difficult to formalize and transmit. Intranets and knowledge-sharing networks can support the spread of tacit knowledge.

Intranets. Many companies are building knowledge management portals on the corpo- rate intranet to give employees an easier way to access and share information. A knowledge management portal is a single, personalized point of access for employees to access multi- ple sources of information on the corporate intranet. Intranets can give people access to ex- plicit knowledge that may be stored in databases, but the greatest value of intranets for knowledge management is increasing the transfer of tacit knowledge. For example, Xerox tried to codify the knowledge of its service technicians and embed it in an expert decision sys- tem that was installed in the copiers. The idea was that technicians could be guided by the system and complete repairs more quickly, sometimes even off-site. However, the project failed because it did not take into account the tacit knowledge—the nuances and details— that could not be codified. After a study found that service techs shared their knowledge pri- marily by telling “war stories,” Xerox developed an intranet system called Eureka to link 25,000 field service representatives. Eureka, which enables technicians to electronically share war stories and tips for repairing copiers, has cut average repair time by 50 percent.128

Organizations typically combine several technologies to facilitate the sharing and trans- fer of both tacit and explicit knowledge. For example, to spur sharing of explicit knowl- edge, a leading steel company set up a centralized data warehouse containing the financial and operational performance data and standards for each business unit. Managers can use business intelligence and other decision tools to identify performance gaps and make changes as needed. The company also enables tacit knowledge transfer through an intranet- based document management system, combined with Web conferencing systems, where worldwide experts can exchange ideas.129 Similarly, when employees of Barclays Global In- vestors are working on proposals from large customers who require answers to hundreds of complex questions, they can access the knowledge network to reuse answers from previous similar proposals. In addition, employees set up online workspaces to tap into subject ex- perts who can collaborate to help answer new kinds of queries and complete proposals faster.130

Overall, IT, including e-business and knowledge management systems, can enable managers to be better connected with employees, customers, partners, and each other.

Source: Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2009), Understanding Management, South-Western College Pub; 8th edition.

29 Apr 2021

6 May 2021

6 May 2021

5 May 2021

5 May 2021

3 May 2021