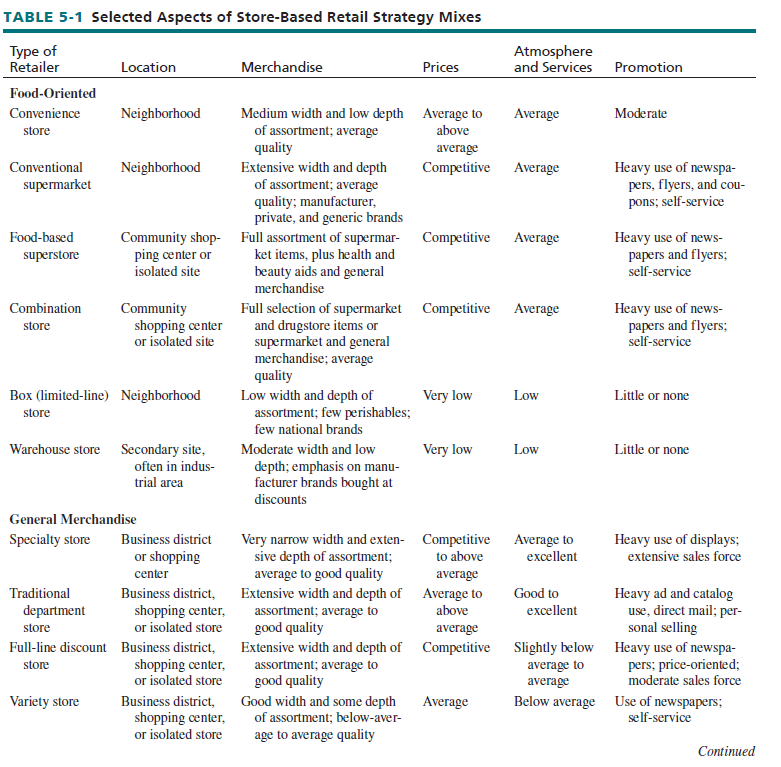

Selected aspects of the strategy mixes of 14 store-based retail institutions, divided into food- oriented and general merchandise groups, are highlighted in this section and in Table 5-1. Although not all-inclusive, these strategy mixes provide a good overview of store-based strategies. Please note that width of assortment is the number of different product lines carried by a retailer; depth of assortment is the selection within the product lines stocked.

1. Food-Oriented Retailers

The following food-oriented strategic retail formats are described next: convenience store, conventional supermarket, food-based superstore, combination store, box (limited-line) store, and warehouse store.

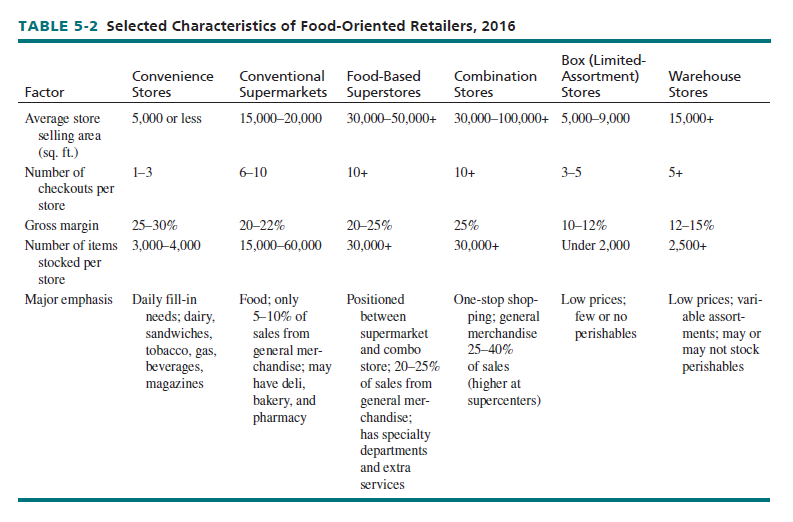

CONVENIENCE STORE A convenience store is typically a well-located, food-oriented retailer that is open long hours and carries a moderate number of items. The store facility is small (only a fraction of the size of a conventional supermarket) and has average to above-average prices and average atmosphere and customer services. The ease of shopping at convenience stores and the impersonal nature of many large supermarkets make convenience stores particularly appealing to their customers, many of whom are male.

There are more than 154,000 U.S. convenience stores (excluding stores where food is a small fraction of revenues), and total annual sales are $215 billion (excluding gasoline).10 7-Eleven (www .7-eleven.com), Circle K (www.circlek.com), Casey’s General Store (www.caseys.com), and Wawa (www.wawa.com) are major food-based U.S. convenience store chains. Speedway (www.speedway .com) is a leading gasoline service-station-based convenience store chain with 2,770 outlets.11

Items such as milk, eggs, and bread once represented the major portion of convenience store sales; today, healthy food options such as packaged salads and fresh whole or cut fruits and vegetables are generating the fastest growth in sales.12 Sandwiches, tobacco products, snack foods, soft drinks, general merchandise, beer and wine, ATMs, and lottery tickets are also key items. Lately, many convenience stores are adding prepared foods. Gasoline generates 30 percent or more of total sales at most of the convenience stores that carry it.

This format’s advantages are its usefulness when a person does not want to travel to or shop at a supermarket, when fill-in items and gas are needed, when store hours are long, and when drive-thru windows are available. Many shoppers visit multiple times a week, and the average transaction is small. Due to limited space, stores get frequent deliveries and have high handling costs. Buyers are less price-sensitive than at other food-oriented stores.

The convenience stores industry does have problems: Some areas are saturated with stores; some stores have become too big, making shopping less convenient; supermarkets now offer longer hours and more nonfood items; a decrease in tobacco purchasing, which is a big sales category; and some chains have had financial woes.

CONVENTIONAL SUPERMARKET A supermarket is a self-service food store with grocery, meat, and produce departments and a minimum annual sales of $2 million. Included are conventional supermarkets, food-based superstores, combination stores, box (limited-line) stores, and warehouse stores. See Figure 5-6.

A conventional supermarket is a departmentalized food store with a wide range of food and related products; sales of general merchandise are rather limited. This institution started more than 85 years ago when it was recognized that large-scale operations would let a retailer combine volume sales, self-service, and low prices. Self-service enabled supermarkets to cut costs as well as increase volume. Personnel costs were reduced, and impulse buying increased. The car and the refrigerator contributed to the supermarket’s success by lowering travel costs and adding to the life span of perishables.

For several decades, overall supermarket sales have been about 70 to 75 percent of U.S. grocery sales, with conventional supermarkets now yielding a fraction of total supermarket sales. There are over 26,000 conventional units, with annual sales of $420 billion.13 Chains account for the great majority of sales. Among the leaders are Kroger (www.kroger.com), Safeway (www .safeway.com), and Publix (www.publix.com), although a number of these firms’ stores are now food-based superstores. Many independent supermarkets are affiliated with cooperative or voluntary organizations such as IGA (www.iga.com) and Supervalu (www.supervalu.com).

Conventional supermarkets generally rely on high inventory turnover (volume sales). Their profit margins are low. In general, average gross margins (selling price less merchandise cost) are 20 to 22 percent of sales, and net profits are 1 to 3 percent of sales.

These supermarkets face intense competition from other food stores: Convenience stores offer easier shopping; food-based superstores and combination stores have more product lines and greater variety within them, as well as better margins; and box and warehouse stores have lower operating costs and prices. Delivery-based food services such as Fresh Direct and AmazonFresh offer the convenience of online ordering and in-home scheduled delivery. Membership clubs (discussed later), with low prices, also provide competition—especially now that they have many expanded food lines. Variations of the supermarket are covered next.

FOOD-BASED SUPERSTORE A food-based superstore is larger and more diversified than a conventional supermarket but usually smaller and less diversified than a combination store. This format originated in the 1970s as supermarkets sought to stem sales declines by expanding store size and the number of nonfood items carried. Some supermarkets merged with drugstores or general merchandise stores, but more grew into food-based superstores. There are 12,000 food- based U.S. superstores, with sales of $280 billion.14

A food-based superstore occupies at least 30,000 to 50,000 square feet of space, and 20 to 25 percent of sales are from general merchandise, such as garden supplies, flowers, small appliances, and DVDs. It caters to complete grocery needs, along with fill-in general merchandise.

Like combination stores, food-based superstores are efficient, offer a degree of one-stop shopping, stimulate impulse purchases, and feature high-profit general merchandise. They also have other advantages: It is easier and less costly to redesign and convert supermarkets into food-based superstores than into combination stores. Many people feel more comfortable shopping in true food stores than in huge combination stores. Management expertise is more focused.

Numerous U.S. supermarket chains have turned more to food-based superstores. They have expanded and remodeled existing supermarkets and built new stores. Many independents have also converted to food-based superstores.

COMBINATION STORE A combination store unites supermarket and general merchandise in one facility, with general merchandise accounting for 25 to 40 percent of sales. The format began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as common checkout areas were used for separately owned supermarkets and drugstores or supermarkets and general merchandise stores. The natural offshoot was integrating operations under one management. The thousands of U.S. combination stores (including supercenters) have annual sales of several hundred billion dollars.15 Combination store leaders are Meijer (www.meijer.com), Fred Meyer (www.fredmeyer.com), and Albertson’s (www .albertsons.com).

Combination stores are large, from 30,000 up to 100,000 or more square feet. This means operating efficiencies and cost savings. Most consumers like one-stop shopping and will travel the extra distance to patronize them. Impulse sales are high. General merchandise often has better margins than food items. Supermarkets and drugstores have commonalities in customers served and the low-price, high-turnover items sold. Drugstore and general merchandise customers are drawn to the store more frequently.

A supercenter is a combination store blending an economy supermarket with a discount department store. It is the U.S. version of the even larger hypermarket (the European institution pioneered by firms such as Carrefour [www.carrefour.com] that did not succeed in the United States). As a rule, the majority of supercenter sales are from nonfood items. Stores usually range from 75,000 to 150,000 square feet in size, and they stock up to 50,000 or more items—much more than the 30,000 or so items carried by other combination stores. Walmart and Target both operate a growing number of supercenters.

BOX (LIMITED-LINE) STORE The box (limited-line) store is a food-based discounter that focuses on a small selection of items, moderate hours of operation (compared with other supermarkets), few services, and limited manufacturer brands. This type of store carries under 2,000 items, few refrigerated perishables, and few sizes and brands per item. Items are displayed in cut cases, and prices are shown on shelves or overhead signs. Customers bag their own purchases. Box stores rely on low-priced, private-label brands. Their prices are 20 to 30 percent below those in supermarkets.

The box store originated in Europe and was exported to the United States in the mid-1970s. The growth of these stores has not been as anticipated, and sales have actually fallen modestly in recent years. Some other food stores have matched box-store prices. Many people are loyal to manufacturer brands, and box stores cannot fulfill one-stop shopping needs. There are 2,500 box stores in the United States, with sales of $14 billion.16 The leading box store operators are Save- A-Lot (http://save-a-lot.com) and Aldi (www.aldi.com).

WAREHOUSE STORE A warehouse store is a food-based discounter that offers a moderate number of food items in a no-frills setting. It appeals to one-stop food shoppers, concentrates on special purchases of popular brands, uses cut-case displays, offers little service, posts prices on shelves, and locates in secondary sites. These stores began in the late 1970s. There are now 1,700 U.S. stores with $70 billion in annual sales.17

The largest warehouse store is known as a superwarehouse. There are more than 600 of them in the United States. They have annual sales exceeding $20 million each, and they contain a variety of departments, including produce. High ceilings accommodate pallet loads of groceries. Shipments are made directly to the store. Customers pack their own groceries in these types of stores. Superwarehouses are profitable at gross margins far lower than for conventional supermarkets. The leading super warehouse chain is Cub Foods (www.cub.com).

Many people do not like shopping in warehouse settings. Also, because products are usually acquired through special deals, brands may be temporarily or permanently out of stock. Table 5-2 shows selected characteristics for the food-oriented retailers just described.

2. General Merchandise Retailers

We now look at the general merchandise retail formats highlighted in Table 5-1: specialty store, traditional department store, full-line discount store, variety store, off-price chain, factory outlet, membership club, and flea market.

SPECIALTY STORE A specialty store concentrates on selling one type of goods or service line, such as young women’s apparel. It usually carries a narrow but deep assortment in the chosen category and tailors the strategy to a given market segment. This enables the store to maintain a better selection and sales expertise than its competitors, which are often department stores. Investments are controlled, and there is a certain amount of flexibility. Among the most popular categories of specialty stores are apparel, personal care, auto supply, home furnishings, electronics, books, toys, home improvement, pet supplies, jewelry, and sporting goods.

Consumers often shop at specialty stores because of the knowledgeable sales personnel, the variety of choices within a given category, customer service, intimate store size and atmosphere (although this is not true of the category killer store), the lack of crowds (also not true of the category killer store), and the absence of aisles of unrelated merchandise that they must pass through. Some specialty stores have elaborate fixtures and upscale merchandise for affluent shoppers, whereas others are discount-oriented and aim at price-conscious consumers. See Figure 5-7.

Total specialty store sales are tough to determine because these retailers sell virtually all kinds of goods and services, and aggregate specialty store data are not compiled by the government. Specialty store leaders include Home Depot (home improvement), Best Buy (consumer electronics), Staples (office supplies), Toys “R” Us (toys), GameStop (videogames), and Bed Bath & Beyond (household furnishings and small appliances).

One type of specialty store—the category killer—has gained particular strength. A category killer (also known as a power retailer) is an especially large specialty store. It features an enormous selection in its category and relatively low prices. Consumers are drawn from wide geographic areas. Home Depot (www.homedepot.com), Barnes & Noble (www.barnesandnoble.com), Sephora (www.sephora.com), and Staples (www.staples.com) are among the chains almost fully based on the concept. Not only is Sephora the leading chain of perfume and cosmetics stores in France but it also has more than 1,900 stores in 29 countries around the world (including 360 stores located in North America). Sephora’s stores sell a broad range of brands in such product categories as makeup, skin care, fragrances, bath and body lotions, lip care, and hair care. In addition, Sephora has its own private label.18

Nonetheless, smaller specialty stores (even ones with under 1,000 square feet of space) can prosper if they are highly focused, offer strong customer service, and avoid imitating larger firms. Shoppers looking to purchase products quickly may not want to spend the time and effort to search through multiple categories and brands at a huge category-killer store and instead may prefer to shop at a smaller specialty store. Some categories of merchandise, such as high-tech consumer electronics products, require greater support from specially trained, knowledgeable employees than the support typically offered at category-killer stores.

Any size specialty store can be adversely affected by seasonality or a decline in the popularity of its product category. This type of store may also fail to attract consumers who are interested in one-stop shopping for multiple product categories.

TRADITIONAL DEPARTMENT STORE A department store is a large retail unit with an extensive assortment (width and depth) of goods and services that is organized into separate departments for purposes of buying, promotion, customer service, and control. It has the most selection of any general merchandise retailer, often serves as the anchor store in a shopping center or district, has strong credit card penetration, and is usually part of a chain. To be classified as a department store, a retailer must sell a wide range of products (such as apparel, furniture, appliances, and home furnishings), and selected other items (such as paint, hardware, toiletries, cosmetics, photo equipment, jewelry, toys, and sporting goods) with no one merchandise line predominating.

Two basic types of retailers meet the preceding criteria: the traditional department store and the full-line discount store. Together, they generate about $680 billion in U.S. revenues annually.19 The traditional department store is discussed next, followed by coverage on the full-line discount store.

At a traditional department store, merchandise quality ranges from average to quite good. Pricing is moderate to above average. Customer service ranges from medium levels of sales help, credit, delivery, and so forth to high levels of each. For example, Macy’s (www.macys.com) targets middle-class shoppers interested in assortment and moderate prices, whereas Bloomingdale’s (www.bloomingdales.com) aims at upscale consumers through more trendy merchandise and higher prices. Few traditional department stores sell all of the product lines that the category used to carry. Many place greater emphasis on apparel and may not carry such lines as furniture, electronics, and major appliances.

Over its history, the traditional department store has contributed many innovations, such as advertising prices, enacting a one-price policy (whereby all shoppers pay the same price for the same item), developing computerized checkouts, offering money-back guarantees, adding branch stores, decentralizing management, and moving into suburban shopping centers. However, in recent years, the performance of traditional department stores has lagged far behind that of fullline discount stores. Today, traditional department store sales ($170 billion annually) represent one-quarter of total department store sales. These are some reasons for traditional department stores’ difficulties:

- Price-conscious consumers are more attracted to discounters and online stores than to traditional department stores.

- These stores no longer have exclusive brands for many of the items they sell.

- The growth of shopping centers has aided specialty stores because consumers can engage in one-stop shopping at several specialty stores in the same shopping center. Department stores do not dominate the smaller stores around them as they once did.

- Specialty stores often have better assortments in the lines they carry.

- Customer service has deteriorated. Often, store personnel are not as loyal, helpful, or knowledgeable as in prior years.

- Some stores are too big and have a lot of unproductive space and low-turnover merchandise.

- Many department stores have had a weak focus on market segments and a fuzzy image.

- Such chains as Sears have repeatedly changed strategies, confusing consumers as to their image. (Is Sears a traditional department store chain or a full-line discount store chain?)

- Some companies are not as innovative in their merchandise decisions as they once were.

Traditional department stores need to clarify their niche in the marketplace (retail positioning); place greater emphasis on customer service and sales personnel; present more exciting, better-organized store interiors; use space better by downsizing stores and eliminating slow-selling items; and open outlets in smaller, less developed towns and cities (as Sears has done). They can also centralize more buying and promotion functions, do better research, and reach customers more efficiently (by such tools as targeted mailing pieces). See Figure 5-8.

FULL-LINE DISCOUNT STORE A full-line discount store is a type of department store with these features:

- It conveys the image of a high-volume, low-cost outlet selling a broad product assortment for less than conventional prices.

- It is more apt to carry the range of general merchandise once expected only at department stores, including electronics, furniture, and appliances—as well as auto accessories, gardening tools, and housewares.

- Shopping carts and centralized checkout service are provided.

- Customer service is not usually provided within store departments but at a centralized area. Products are normally sold via self-service with minimal assistance in any single department.

- Nondurable (soft) goods often feature private brands, whereas durable (hard) goods emphasize well-known manufacturer brands.

- Less fashion-sensitive merchandise is often carried.

- Buildings, equipment, and fixtures are less expensive; and operating costs are lower than for traditional department stores and specialty stores.

Annual U.S. full-line discount store revenues are $510 billion (including general merchandise-based supercenters and leased departments), roughly 75 percent of all U.S. department store sales. Together, Walmart (www.walmart.com) and Target (www.target.com) operate 7,400 full-line discount stores (including supercenters) in the United States alone.20

The success of full-line discount stores is due to many factors. They have a clear customer focus: middle-class and lower-middle-class shoppers looking for good value. The stores feature popular brands of average- to good-quality merchandise at competitive prices. They have expanded their goods and service categories and often have their own private brands. Full-line discount stores have worked hard to improve their image and provide more customer services. The average outlet (not the supercenter) tends to be smaller than a traditional department store, and sales per square foot are usually higher, which improves productivity. Some full-line discount stores are located in small towns where competition is less intense. Facilities may be newer than those of many traditional department stores.

The greatest challenges facing full-line discount stores are the competition from other retailers (especially lower-priced store discounters, category killer stores, and Web-based retailers such as Amazon.com and eBay), too rapid expansion of some firms, saturation of prime locales, and the dominance of Walmart and Target (as Kmart has fallen dramatically from its heyday). The industry has undergone a number of consolidations, bankruptcies, and liquidations.

VARIETY STORE A variety store handles an assortment of inexpensive and popularly priced goods and services, such as apparel and accessories, costume jewelry, notions and small wares, candy, toys, and other items in the price range. There are open displays and few salespeople. The stores do not carry full product lines, may not be departmentalized, and do not deliver products. Although the conventional variety store format has faded away, there are two successful spin-offs from it: dollar discount stores and closeout chains.

Dollar discount stores sell similar items to those in conventional variety stores but in plainer surroundings and at much lower prices. They generate $40 billion in yearly sales. Dollar General and Dollar Tree (which acquired Family Dollar in 2015) are the two leading dollar discount store chains. The two firms operate over 26,000 stores and have about $35 billion in annual sales. Closeout chains sell similar items to those in conventional variety stores but feature closeouts and overruns. They account for $8 billion in sales annually. Big Lots (www.biglots.com) is the leader in that category with about 1,460 stores and annual sales of $5.2 billion.21

The conventional variety store format (which included Woolworths and McCrorys) pretty much disappeared from the U.S. marketplace in the mid-1990s after a long, successful run. What happened? There was heavy competition from specialty stores and discounters, most of the stores were older facilities, and some items had low profit margins. At one time, Woolworths had 1,200 variety stores with annual sales of $2 billion.

OFF-PRICE CHAIN An off-price chain features brand-name (sometimes designer) apparel and accessories, footwear (primarily women’s and family), linens, fabrics, cosmetics, and/or housewares and sells them at everyday low prices in an efficient, limited-service environment. It frequently has community dressing rooms, centralized checkout counters, no gift wrapping, and extra charges for alterations. The chains buy merchandise opportunistically, as special deals occur. Other retailers’ canceled orders, manufacturers’ irregulars and overruns, and end-of-season items are often purchased for a fraction of their original wholesale prices. The total sales of U.S. off- TJX (www.tjx.com) price apparel stores are $55 billion. The biggest chains are T. J. Maxx (www.tjmaxx.com) and Marshalls (www.marshalls.com) (both owned by TJX), Ross Stores (www.rossstores.com), and Burlington Coat Factory, now advertised as Burlington (www.burlingtoncoatfactory.com).

Oil-price chains aim at the same shoppers as traditional department stores do—but with prices reduced by 40 to 50 percent. Shoppers are also lured by the promise of new merchandise on a regular basis. See Figure 5-9.

The most crucial strategic element for off-price chains involves buying merchandise and establishing long-term relationships with suppliers. To succeed, the chains must secure large quantities of merchandise at reduced wholesale prices and have a regular flow of goods into the stores. Sometimes manufacturers use off-price chains to sell samples, products that are not doing well when they are introduced, and remaining merchandise near the end of a season. At other times, off-price chains employ a more active buying strategy. Instead of waiting for closeouts and canceled orders, they convince manufacturers to make merchandise during off-seasons and will pay cash for items early. Off-price chains are less demanding in terms of the support requested from suppliers; they do not return products and they pay promptly.

Off-price chains face some market pressure because of competition from other institutional formats that run frequent sales throughout the year, such as temporary pop-up stores and factory outlets. In addition, they have disadvantages associated with discontinuity of merchandise, poor management at some firms, insufficient customer service for some shoppers, and the shakeout of underfinanced companies.

FACTORY OUTLET A factory outlet is a manufacturer-owned store that sells closeouts, discontinued merchandise, irregulars, canceled orders, and sometimes in-season, first-quality merchandise. Manufacturers’ interest in outlet stores has risen for four basic reasons:

- Manufacturers can control where their discounted merchandise is sold. By placing outlets in out-of-the-way spots with low sales penetration of the firm’s brands, outlet revenues do not affect relationships with key specialty and department store accounts.

- Outlets are profitable despite prices being up to 60 percent less than customary retail prices. Profits are due to low operating costs—few services, low rent, limited displays, and plain store fixtures—and selling more merchandise made especially for outlet stores.

- The manufacturer decides on store visibility, sets promotion policies, removes labels, and ensures that discontinued items and irregulars are disposed of properly.

- Because many specialty and department stores are increasing private-label sales, manufacturers need revenue from outlet stores to sustain their own growth.

More factory stores now locate in clusters or outlet malls to expand customer traffic, and they use cooperative ads. The states with a large number of outlet centers are California, Florida, Texas, Pennsylvania, and New York. The largest U.S. factory outlet mall is Woodbury Common Premium Outlets (located in Central Valley, New York) with 904,000 gross leasable square feet.

There are more than 200 outlet malls nationwide.22 Firms with a major presence include Phillips-Van Heusen Corp. (Tommy Hilfiger, Calvin Klein, and Arrow); Ascena Retail Group (Dress Barn, Maurices, Justice, Lane Bryant, and Catherines); Gap Inc. (Gap and Banana Republic); JAG Footwear; and Carter’s, Inc. (children’s clothing). Worldwide factory outlet sales equaled $46 billion in 2015.

Large outlet centers are in Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and other states. There are more than 15,000 U.S. factory outlet stores representing hundreds of manufacturers, many in outlet malls. These stores have $27 billion in U.S. yearly sales, with three-quarters from apparel and accessories. Firms with a mall presence include Bass (footwear); Polo Ralph Lauren (apparel); Levi’s (apparel); Nike (apparel and footwear); Samsonite (luggage); and Totes (rain gear).

When deciding whether to utilize factory outlets, manufacturers must be cautious. They must evaluate their own retailing expertise, the investment costs, the impact on existing retailers that buy from them, and the response of consumers. Manufacturers do not want to jeopardize their products’ sales at full retail prices.

MEMBERSHIP CLUB A membership (warehouse) club straddles the line between wholesaling and retailing. It appeals to price-conscious consumers, who must be members to shop there. Some members are small business owners and employees who pay a membership fee to buy merchandise at wholesale prices. They make purchases for use in operating their firms or for personal use and yield 60 percent of club sales. Most members are final consumers who buy for their own use; they represent 40 percent of club sales. They must pay an annual fee to be a member. Prices may be slightly more than for business customers. There are over 1,500 U.S. membership clubs, with annual sales to final consumers of $75 billion. Costco www .costco.com) and Sam’s Club (www.samsclub.com) generate over 90 percent of industry sales.23

The operating strategy of today’s membership club centers on large stores (up to 100,000 or more square feet), inexpensive sites, opportunistic buying (with some product discontinuity), a fraction of the items stocked by full-line discount stores, little advertising, warehouse-style fixtures, wide aisles to give forklift trucks access to shelves, concrete floors, limited delivery, and low prices. A typical club carries general merchandise, such as consumer electronics, appliances, computers, housewares, tires, and apparel (35 to 60 percent of sales); food (20 to 35 percent); and sundries, such as health and beauty aids, tobacco, liquor, and candy (15 to 30 percent). It may have a pharmacy, photo developing, a car-buying service, a gas station, and other items once seen as frills for this format. Inventory turnover is several times that of a department store.

The major retailing challenges relate to the allocation of efforts between business and final consumer accounts (without antagonizing one group or the other and without presenting a blurred image), the lack of interest by many consumers in shopping at warehouse-type stores, the power of the two industry leaders, and the potential for saturation caused by overexpansion.

FLEA MARKET At a flea market, many retail vendors sell a range of products at discount prices in plain surroundings. It is rooted in the centuries-old tradition of street selling—shoppers touch and sample items, and haggle over prices. Vendors used to sell only antiques, bric-a-brac, and assorted used merchandise. Today, they also frequently sell new goods, such as clothing, cosmetics, watches, consumer electronics, housewares, and gift items. See Figure 5-10.

Many flea markets are in nontraditional sites such as racetracks, stadiums, and arenas. Some are at sites abandoned by other retailers. Typically, vendors rent space; depending on location, a flea market might rent individual spaces for $30 to $100 or more a day. Some flea markets impose a parking fee or admission charge for shoppers.

There are a few hundred major U.S. flea markets, but overall sales data are not available. The credibility of permanent flea markets, consumer interest in bargaining, a broader product mix, availability of brand-name goods, and low prices all contribute to the format’s appeal. A popular site is the Rose Bowl Flea Market (www.rgcshows.com/rosebowl.aspx), which is open the second Sunday of each month. It regularly features 2,500 vendors and attracts 20,000 shoppers a day. The only restricted items are “food, animals, guns, ammunition, pornography, and services requiring physical contact.” A vendor space costs from $60 to $250 for 1 day.

At a flea market, price haggling is common, cash is the predominant currency, and many vendors gain their first real experience as retail entrepreneurs. One twenty first-century trend involves nonstore, Web-based flea markets such as eBay (www.ebay.com), eBid (www.ebid .com), OnlineAuction (www.onlineauction.com), and Skoreit! (www.skoreit.com). Online auction sites account for several billion dollars in sales annually and are popular among bargain hunters.

Many traditional retailers believe flea markets represent an unfair method of competition because the quality of merchandise may be misrepresented, consumers may buy items at flea markets and return them to other retailers for higher refunds, suppliers are often unaware their products are sold there, sales taxes can be easily avoided, and operating costs are quite low. Flea markets may also cause traffic congestion.

The high sales volume from off-price chains, factory outlets, membership clubs, and flea markets is explained by the wheel of retailing. These institutions are low-cost operators appealing to price-conscious consumers who are not totally satisfied with other retail formats that have upgraded their merchandise and customer service, raised prices, and moved along the wheel.

Source: Barry Berman, Joel R Evans, Patrali Chatterjee (2017), Retail Management: A Strategic Approach, Pearson; 13th edition.

Very interesting info !Perfect just what I was looking for!

You are my intake, I own few web logs and rarely run out from to post .