Price is not just a number on a tag. It comes in many forms and performs many functions. Rent, tuition, fares, fees, rates, tolls, retainers, wages, and commissions are all the price you pay for some good or service. Price also has many components. If you buy a new car, the sticker price may be adjusted by rebates and dealer incentives. Some firms allow customers to pay through multiple forms, such as $150 plus 25,000 frequent flier miles for a flight.2

Throughout most of history, prices were set by negotiation between buyers and sellers. Bargaining is still a sport in some areas. Setting one price for all buyers is a relatively modern idea that arose with the development of large-scale retailing at the end of the nineteenth century. F. W. Woolworth, Tiffany & Co., John Wanamaker, and others advertised a “strictly one-price policy,” efficient because they carried so many items and supervised so many employees.

1. PRICING IN A DIGITAL WORLD

Traditionally, price has operated as a major determinant of buyer choice. Consumers and purchasing agents who have access to price information and price discounters put pressure on retailers to lower their prices. Retailers in turn put pressure on manufacturers to lower their prices. The result can be a marketplace characterized by heavy discounting and sales promotion.

Downward price pressure from a changing economic environment coincided with some longer-term trends in the technological environment. For some years now, the Internet has been changing the way buyers and sellers interact. Here is a short list of how the Internet allows sellers to discriminate between buyers and buyers to discriminate between sellers.

Buyers can:

- Get instant price comparisons from thousands of vendors. Customers can compare the prices offered by multiple retailers by clicking mySimon.com. Intelligent shopping agents (“bots”) take price comparison a step further and seek out products, prices, and reviews from hundreds if not thousands of merchants.

- Check prices at the point of purchase. Customers can use smart phones to make price comparisons in stores before deciding whether to purchase, pressure the retailer to match or better the price, or buy elsewhere.

- Name their price and have it met. On Priceline.com, customers state the price they want to pay for an airline ticket, hotel, or rental car, and the site looks for any seller willing to meet that price.3 Volume-aggregating sites combine the orders of many customers and press the supplier for a deeper discount.

- Get products free. Open source, the free software movement that started with Linux, will erode margins for just about any company creating software. The biggest challenge confronting Microsoft, Oracle, IBM, and virtually every other major software producer is: How do you compete with programs that can be had for free? “Marketing Insight: Giving It All Away” describes how firms have been successful with essentially free offerings.

Sellers can:

- Monitor customer behavior and tailor offers to individuals. GE Lighting, which gets 55,000 pricing requests a year from its B-to-B customers, has Web programs that evaluate 300 factors going into a pricing quote, such as past sales data and discounts, so it can reduce processing time from up to 30 days to six hours.

- Give certain customers access to special prices. Ruelala is a members-only Web site that sells upscale women’s fashion, accessories, and footwear through limited-time sales, usually two-day events. Other business marketers are already using extranets to get a precise handle on inventory, costs, and demand at any given moment in order to adjust prices instantly.

Both buyers and sellers can:

- Negotiate prices in online auctions and exchanges or even in person. Want to sell hundreds of excess and slightly worn widgets? Post a sale on eBay. Want to purchase vintage baseball cards at a bargain price? Go to baseball-cards.com. According to Consumer Reports, more than half of U.S. adults reported bargaining for a better deal on everyday goods and services in the past three years; almost 90 percent were successful at least once. Some successful tactics included: told salesperson I’d check competitor’s prices (57 percent of respondents); looked for lower prices at a walk-in store (57 percent); chatted with salesperson to make a personal connection (46 percent); used other store circulars or coupons as leverage (44 percent); and checked user reviews to see what others paid (39 percent).4

2. A CHANGING PRICING ENVIRONMENT

Pricing practices have changed significantly, thanks in part to a severe recession in 2008-2009, a slow recovery, and rapid technological advances. But the new millennial generation also brings new attitudes and values to consumption. Often burdened by student loans and other financial demands, members of this group (born between about 1977 and 1994) are reconsidering just what they really need to own. Renting, borrowing, and sharing are valid options to many.

Some say these new behaviors are creating a sharing economy in which consumers share bikes, cars, clothes, couches, apartments, tools, and skills and extracting more value from what they already own. As one sharing- related entrepreneur noted, “We’re moving from a world where we’re organized around ownership to one organized around access to assets.” In a sharing economy, someone can be both a consumer and a producer, reaping the benefits of both roles.5

Trust and a good reputation are crucial in any exchange, but imperative in a sharing economy. Most platforms that are part of a sharing-related business have some form of self-policing mechanism such as public profiles and community rating systems, sometimes linked with Facebook. Let’s look at bartering and renting, two pillars of a sharing economy.

BARTERING Bartering, one of the oldest ways of acquiring goods, is making a comeback through transactions estimated to total $12 billion annually in the United States. Trade exchange companies like Florida Barter and Web sites like www.swap.com connect people and businesses seeking win-win solutions. One financial analyst has traded financial plans to clients in return for a tutorial in butter churning and trapeze and fire-breathing lessons. ThredUP allows parents to swap kids’ outgrown and unused clothing and toys with other parents in similar situations all over the United States. Zimride is a ride-sharing social network for college campuses.6

Experts advise using barter only for goods and services that someone would be willing to pay for anyway. The founders of a Web site for swapping sporting goods and outdoor gear drew up these criteria for sharable objects: cost more than $100 but less than $500, easily transportable, and infrequently used.7

RENTING The sector of the new sharing economy that is really exploding is rentals. RentTheRunway offers affordable rentals of designer dresses. Customers are sent two different sizes of the dress they choose—to ensure better fit—at a cost of $50 to $300, or about 10 percent of retail value. The site is adding 100,000 customers a month, typically 15 to 35 years old.8 One of the pioneers in the rental economy is Airbnb.9

AIRBNB Rhode Island School of Design graduates Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia came upon the idea of making a little extra money by launching www.airbedandbreakfast.com and renting out air mattresses to attendees at an industrial design conference in San Francisco. Emboldened by their success at attracting three very different guests for a week, the two shortened the name of their venture to Airbnb, hired a tech expert, and set out to extend their “couch-surfing” business by adding features such as escrow payments and professional photography so the potential rental properties looked their best. Around-the-clock customer service for guests and a $1 million insurance policy for hosts provided each party with valuable peace of mind. All kinds of spaces were included—not just rooms, apartments, and houses but also driveways, treehouses, igloos, and even castles. Airbnb applied a broker’s model to generate revenues: 3 percent from the host and 6 percent to 12 percent from the guest, depending on the property price. Although it now operates in 190 countries and 28,000 cities, books millions of spaces annually, and has seen its valuation approach $10 billion, it faces several significant challenges, including government intervention in the form of taxes, disputes over illegal subletting, and the imposition of safety and other hospitality-related regulation.

Even big companies are getting in on the act. German car maker Daimler introduced its Car2Go service for customers who want to rent a car for a short period of time—even at the spur of the moment. In about half its stores, Home Depot has a unit that rents out all kinds of products such as drills and saws that it also sells.10

3. MARKETING Insight Giving It All Away

Giving away products for free via sampling has been a successful marketing tactic for years. Estee Lauder gave free samples of cosmetics to celebrities, and organizers at awards shows lavish winners with plentiful free items or gifts known as “swag.” Other manufacturers, such as Gillette and HP, built their business model around selling the host product essentially at cost and making money on the sale of necessary supplies, such as razor blades and printer ink.

Software companies adopted similar practices. Adobe gave away its Adobe Reader for free in 1994, as did Macromedia with its Shockwave player in 1995. Their software became the industry standard, but the firms really made their money selling their authoring software. More recently, start-ups such as Blogger Weblog and Skype have succeeded with a “freemium” strategy—free online services with a premium component.

Chris Anderson, former editor-in-chief of Wired, believes that in a digital marketplace companies can make money with free products. As evidence, he offers revenue models relying on crosssubsidies (giving away a DVR to sell cable service) and freemiums (offering the Flickr online photo management and sharing application for free to everyone while selling the superior Flickr Pro to more committed users).

Some online firms have successfully moved “from free to fee” and begun charging for services. Under a new participative-pricing mechanism that lets consumers decide on the price they feel is warranted, buyers often choose to pay more than zero, and even enough for sellers’ revenues to increase over what a fixed price would have yielded.

Red Hat successfully applied a “freemium” model. A pioneer with open source Linux software, the company offers its business customers stability and dependability. Every few years it freezes a version of the constantly evolving software and sells a long-term support edition with customized applications, backdated updates from later versions of Linux, and customer support, all for a subscription fee. Red Hat also works with developers and programmers for its free version of Linux via its Fedora program. Thanks to these moves, Red Hat is now a billion- dollar company serving 80 percent of the Fortune 500 companies.

Sources: Ashlee Vance, “Red Hat Sees Lots of Green,” Bloomberg Businessweek, March 29, 2012; Jon Brodkin, “How Red Hat Killed Its Core Product—and Became a Billion-Dollar Business,” www.arstechnica.com, February 28, 2012; Chris Anderson, Free: The Future of a Radical Price (New York: Hyperion, 2009); Ju-Young Kim, Martin Natter, and Martin Spann, “Pay What You Want: A New Participative Pricing Mechanism,” Journal of Marketing 73 (January 2009), pp. 44-58; Koen Pauwels and Allen Weiss, “Moving from Free to Fee: How Online Firms Market to Change Their Business Model Successfully,” Journal of Marketing 72 (May 2008), pp. 14-31.

4. HOW COMPANIES PRICE

In small companies, the boss often sets prices. In large companies, division and product line managers do. Even here, top management sets general pricing objectives and policies and often approves lower management’s proposals.

Where pricing is a key competitive factor (aerospace, railroads, oil companies), companies often establish a pricing department to set or assist others in setting appropriate prices. This department reports to the marketing department, finance department, or top management. Others who influence pricing include sales managers, production managers, finance managers, and accountants. In B-to-B settings, research suggests that pricing performance improves when pricing authority is spread horizontally across the sales, marketing, and finance units and when there is a balance in centralizing and delegating that authority between individual salespeople and teams and central management.11

Many companies do not handle pricing well and fall back on “strategies” such as: “We calculate our costs and add our industry’s traditional margins.” Other common mistakes are not revising price often enough to capitalize on market changes; setting price independently of the rest of the marketing program rather than as an intrinsic element of market-positioning strategy; and not varying price enough for different product items, market segments, distribution channels, and purchase occasions.

For any organization, effectively designing and implementing pricing strategies requires a thorough understanding of consumer pricing psychology and a systematic approach to setting, adapting, and changing prices.

5. CONSUMER PSYCHOLOGY AND PRICING

Many economists traditionally assumed that consumers were “price takers” who accepted prices at face value or as a given. Marketers, however, recognize that consumers often actively process price information, interpreting it from the context of prior purchasing experience, formal communications (advertising, sales calls, and brochures), informal communications (friends, colleagues, or family members), point-of-purchase or online resources, and other factors.12

Purchase decisions are based on how consumers perceive prices and what they consider the current actual price to be—not on the marketer’s stated price. Customers may have a lower price threshold, below which prices signal inferior or unacceptable quality, and an upper price threshold, above which prices are prohibitive and the product appears not worth the money. Different people interpret prices in different ways. Consider the consumer psychology involved in buying a simple pair of jeans and a T-shirt.13

JEANS AND A T-SHIRT Why does a black T-shirt for women that looks pretty ordinary cost $275 from Armani but only $14.90 from the Gap and $7.90 from Swedish discount clothing chain H&M? Customers who purchase the Armani T-shirt are paying for a more stylishly cut T-shirt made of 70 percent nylon, 25 percent polyester, and 5 percent elastane with a “Made in Italy” label from a luxury brand known for suits, handbags, and evening gowns that sell for thousands of dollars. The Gap and H&M shirts are made mainly of cotton. For pants to go with that T-shirt, choices abound. Gap sells its “Original Khakis” for $44.50, though Abercrombie & Fitch’s classic button-fly chinos cost $70. But that’s a comparative bargain compared to Michael Bastian’s plain khakis for $480 or Giorgio Armani’s for $595. High-priced designer jeans may use expensive fabrics such as cotton gabardine and require hours of meticulous hand-stitching to create a distinctive design, but equally important are an image and a sense of exclusivity.

Understanding how consumers arrive at their perceptions of prices is an important marketing priority. Here we consider three key topics—reference prices, price-quality inferences, and price endings.

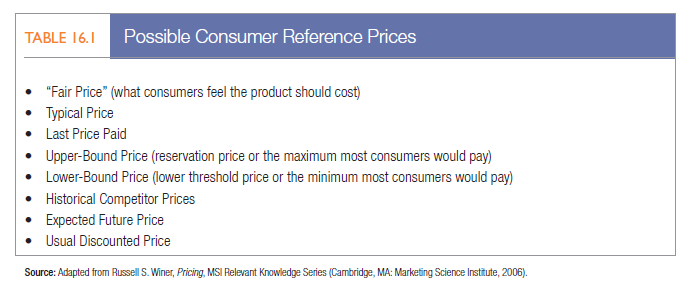

REFERENCE PRICES Although consumers may have fairly good knowledge of price ranges, surprisingly few can accurately recall specific prices.14 When examining products, however, they often employ reference prices, comparing an observed price to an internal reference price they remember or an external frame of reference such as a posted “regular retail price”15

All types of reference prices are possible (see Table 16.1), and sellers often attempt to manipulate them. For example, a seller can situate its product among expensive competitors to imply that it belongs in the same class. Department stores will display women’s apparel in separate departments differentiated by price; dresses in the more expensive department are assumed to be of better quality.16 Marketers also encourage reference-price thinking by stating a high manufacturer’s suggested price, indicating that the price was much higher originally, or by pointing to a competitor’s high price.17

When consumers evoke one or more of these frames of reference, their perceived price can vary from the stated price.18 Research has found that unpleasant surprises—when perceived price is lower than the stated price—can have a greater impact on purchase likelihood than pleasant surprises.19 Consumer expectations can also play a key role in price response. On Internet auction sites such as eBay, when consumers know similar goods will be available in future auctions, they will bid less in the current auction.20

Clever marketers try to frame the price to signal the best value possible. For example, a relatively expensive item can look less expensive if the price is broken into smaller units, such as a $500 annual membership for “under $50 a month,” even if the totals are the same.21

PRICE-QUALITY INFERENCES Many consumers use price as an indicator of quality. Image pricing is especially effective with ego-sensitive products such as perfumes, expensive cars, and designer clothing. A $100 bottle of perfume might contain $10 worth of scent, but gift givers pay $100 to communicate their high regard for the receiver.

Price and quality perceptions of cars interact. Higher-priced cars are perceived to possess high quality. Higher- quality cars are likewise perceived to be higher priced than they actually are. When information about true quality is available, price becomes a less significant indicator of quality. When this information is not available, price acts as a signal of quality.

Some brands adopt exclusivity and scarcity to signify uniqueness and justify premium pricing. Luxury-goods makers of watches, jewelry, perfume, and other products often emphasize exclusivity in their communication messages and channel strategies. For luxury-goods customers who desire uniqueness, demand may actually increase price because they then believe fewer other customers can afford the product.22

To maintain its air of exclusivity, Ferrari deliberately curtailed sales of its iconic, $200,000-or-more Italian sports car to below 7,000 despite growing demand in China, the Middle East, and the United States. But even exclusivity and status can vary by customer. Brahma beer is a no-frills light brew in its home market of Brazil but has thrived in Europe, where it is seen as “Brazil in a bottle.” Pabst Blue Ribbon is a retro favorite among U.S. college students, but its sales have exploded in China where an upgraded bottle and claims of being “matured in a precious wooden cask like a Scotch whiskey” allow it to command a $44 price tag.23

PRICE ENDINGS Many sellers believe prices should end in an odd number. Customers perceive an item priced at $299 to be in the $200 rather than the $300 range; they tend to process prices “left to right” rather than by rounding.24 Price encoding in this fashion is important if there is a mental price break at the higher, rounded price.

Another explanation for the popularity of “9” endings is that they suggest a discount or bargain, so if a company wants a high-price image, it should probably avoid the odd-ending tactic.25 One study showed that demand actually increased one-third when the price of a dress rose from $34 to $39 but was unchanged when it rose from $34 to $44.26

Prices that end with 0 and 5 are also popular and are thought to be easier for consumers to process and retrieve from memory. “Sale” signs next to prices spur demand, but only if not overused: Total category sales are highest when some, but not all, items in a category have sale signs; past a certain point, sale signs may cause total category sales to fall.27

Pricing cues such as sale signs and prices that end in 9 are more influential when consumers’ price knowledge is poor, when they purchase the item infrequently or are new to the category, and when product designs vary over time, prices vary seasonally, or quality or sizes vary across stores.28 They are less effective the more they are used. Limited availability (for example, “three days only”) also can spur sales among consumers actively shopping for a product.29

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

19 May 2021

20 May 2021

19 May 2021

20 May 2021

19 May 2021

19 May 2021