Every business has startup costs; how much and what type will depend greatly on what you’re going to do for a living. If you are going to be office-based or you’re going to have a storefront, your costs will differ than someone who is going to run an Internet operation. Here are some basics for you to consider:

1. Office

Whether or not to have an office is a difficult choice. I was chatting with a multibillionaire gentleman who is quite famous, and he was remarking how he used to have a highly impressive office, but then realized (paraphrasing here), “Heck, I just want to wear my shorts all day, why do I need this office?” and converted his living room into his office. Even his employees, when he has them, work from there—or from their own homes. I’ve had both—a home office and an outside office. I’ll describe each and give you some of my personal pros and cons.

When I was running my computer consulting business, I was a “kid.” I say this because I was in my very early 20s, and I had started it in my teens. I decided one day that I wanted a place to store equipment and I wanted my contractors to have a home base—I wanted a desk, and I wanted legitimacy. I think legitimacy was the biggest reason I wanted to move my office out of my laptop!

One of my clients happened to own the office building where his practice was and he offered me a suite, five rooms for $300 a month. In today’s money this would be about $550—still a really good deal. It would come complete with a sign on the door—and a sign on the street in the business complex. I was a legit business! I moved in, they paid for new carpet (talk about lucky), and I bought IKEA furniture, a few file cabinets, some whiteboards, some entryway furniture (that I never used, because not one client came into my business), and I was happy. I left work at lunchtime and then again after work and I’d go to my office, do my work, pay my contractors, answer calls that had come in, schedule appointments and work for the next day or week, run quotes, and pick up equipment. I staged new systems there, had my “ghosting equipment,” hardware that copies computer hard drive data running with a very strong up-time, and my contractors worked from there. I paid nearly nothing in rent.

This was a bad move! Why was this bad? Because I didn’t need it! Not one person ever came to my office but my team, and my team could stage their computers from anywhere. My work was onsite—I went to my clients. That was the entire idea behind my service—so I didn’t need the not-so-fancy office with new carpet. I moved out about two years later and moved back into my laptop. While it wasn’t nearly as fancy or nearly as “legit” feeling, I got to keep an extra $300 per month for myself and pump it back into my business. (The constant barrage of solicitors stopped, too—they couldn’t knock on my laptop!)

Years later, I began another business—online education and real estate consulting. While they sound highly dissimilar, they have more in common than one might think. I taught online—one class or so here and there—for about ten years. One day toward the end of my doctorate, my dissertation chairperson said, “Hey I do this full time.” I was shocked. He really taught online and made a living at it? I thought to myself, “Wait, he lives in a lower-cost area than I do; I pay nearly double the tax he does. I’d have to do double the work.” Turns out, I have double the energy and half the family commitments (and I can type really fast!).

So began the quest for a few additional schools to add to my income and fill up my free time, eight years after my first online teaching job. After less than a year and a Ph.D. almost finished, I had equal pay from schools as I did from my day job. To my astonishment, I was winning quality awards—in both of my careers! Obviously the quality of my work wasn’t suffering. What if I added to my workload? So I did, and so I left—my day job, that is. I eventually decided to market my additional expertise—my advanced concepts of statistical models and my expertise in technology, management, real estate, entrepreneurship, and so on—and decided to design courses, further expanding my offerings. I began writing books about what I was seeing in the market—again an expansion. Then the television appearances started, the expertise began to flow, and the research I embarked on more than doubled. Products were added to my list, and the product/service mix was working very well. But guess what? This was all done from my home office—the loft in my 2400-square-foot home.

The lesson here? I was too focused in my early days on what it meant to have an office and not what it meant to have a business. I was looking at what would make me feel good, not what I needed. In the right career, working from anywhere would make me feel good. I toy now and again with the idea of renting space in a gorgeous tower off the 405 freeway, but then I remind myself that it would all be for show.

I did find a nice compromise, one you might find useful yourself. I moved into a new home last year, a bit larger, with a casita—a guest house. The guest house is … yes, you guessed it, my new office. It’s a building apart from home, giving me home/work separation, but a low cost one—and a tax write off to boot!

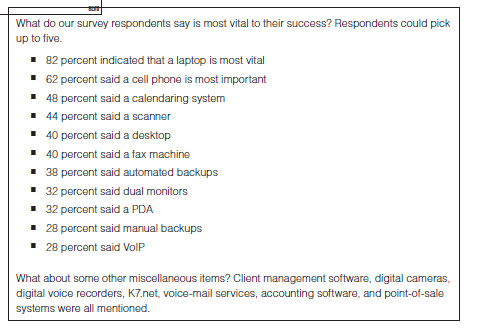

2. Technology

As with anything in life or business, what you need depends on what you’re doing. The same goes for technology. I am an online professor primarily, an author and a speaker, and an analyst. What am I using as my home PC? A machine I built seven years ago. I’ve upgraded parts as they’ve died off (that old IT business expertise comes in handy once in a while, like when I try to figure out just where the smoke is coming from in the grey box under my desk), but I have a (very) fast Internet connection, a large monitor, a comfortable chair, and an old—a very old—PC. My websites are stored on some virtual server somewhere in who-knows-what-country, and they are reliable and cheap.

If you’re going to host a site like eBay or Amazon, you obviously can’t do this. You need to analyze what you do need. How many calls will you make? Do you need a fax? Will a free electronic fax do? Can you use a cell for all your calls? What sort of backups do you need? Do you really need QuickBooks, or will your bank offer you a small business service that lets you invoice clients and handle payroll online?

Once you get a good list, figure out what it will cost and then set a budget and stick to it. Try not to get sucked in with all the bells and whistles. You probably don’t need Blu-ray on that work computer!

3. Staffing

To staff or not to staff—the age old question. You may want to begin your business with just you—for a while, you may well be your business. If you’re going to hire staff, though, you will need to consider all costs involved. In each state, this will vary greatly. The U.S. Department of Labor has some great resources that will help you determine the cost for employees. Here is how they break it down (keep in mind that this is for workers of all categories; these are averages including highly skilled workers with doctorates all the way down to the lowest skilled, most uneducated workers)—the key to take from this section is how much more it will cost you to employ someone than just their wage.

Overall in the United States, a worker earning a salary of $18.67 per hour (average for December 2007 in private industry) cost the employer an additional $7.75 in fees, resulting in a cost of about $26.42 per hour.

In the Northeast, the average salary is $20.99 per hour, with an additional $9.20 in costs, for a total average of $30.18. In the West, this is $20.05, with an additional $8.22 in costs, for a total of $28.27. In the Midwest, it is $17.93 with an additional $7.71 in benefits, for a total of $25.63. Finally, in the South, it is $16.99 in wages and $6.65 in benefits, for a total of $23.64.

In nearly all cases, benefits are running about 30 percent or more for employees! Some benefits are legally required, some are not. In some states, for instance, you must provide healthcare and in others you don’t. Legally required benefits are Social Security, workers’ compensation, and unemployment insurance.

These average around $2.50 per hour per worker. Note that these figures assume straight time, and no overtime or bonuses. (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2008)

What is the take-away lesson here? Having employees isn’t cheap. You may only need moderately skilled workers who you can pay less than the average; remember that these numbers include the highly educated and senior professionals.

There is another option, and that is contractors. There are rules, though, about contractors that you need to strictly abide by!

Initially it is up to you whether you want to bring someone on as a contractor or as an employee. But this is subject to potential review by the IRS and state workers’ compensation and unemployment compensation agencies. The IRS is most likely to classify a person as an independent contractor if she …

- Is capable of earning a profit or loss from an activity.

- Provides her own materials and tools needed to do the job.

- Is paid by the job.

- Works for more than one company at a time.

- Pays her own business and travel expenses—you don’t reimburse her for mileage, and so on.

- Pays and hires assistants.

- Has flexible working hours.

There are common law rules according to the IRS, too. Does the company control or have the right to control what the worker does and how the worker does his job? If so, he may be considered an employee. Does the business provide tools and reimburse for travel and mileage and expenses? If so, he may be an employee. Are there written contracts or benefits like vacations, pension plans, and insurance? If so, he may be an employee. There is no magic bullet that makes a person an employee or a contractor. The entire relationship is taken into consideration, including flexibility and control. The IRS does offer form SS-8, Determination of Worker Status for Purpose of Federal Employment Taxes and Income Tax Withholding, available in the References section of this book. (Internal Revenue Service)

If you are going to hire contractors, you must require a W9 form from your contractors, which is a taxpayer identification number and certification. You can get the W9 form online at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/fw9.pdf?portlet=3. Then you file a simple 1099 MISC form at the end of each year. The money you pay them comes off your taxable income and you don’t withhold taxes from them.

Life is a bit more complicated with employees. You must withhold federal income tax using form W4. Publication 15, “The Employers’ Tax Guide,” available on the IRS website, will walk you through this. Grab Publication 15A, “The Employers’ Supplemental Tax Guide,” while you’re there.

Social Security and Medicare taxes pay for benefits that workers and families receive under the Federal Insurance Contributions Act, or FICA. You must pay a portion of these as well. Social Security tax pays for benefits under the old age, survivors, and disability insurance part of FICA. Medicare pays for benefits under the hospital insurance part of FICA. These also need to be withheld and you pay a matching amount yourself, which adds costs.

You will have to file quarterly Form 941, the Employers’ Quarterly Federal Tax Return.

You will have to file Form 944, the Employers’ Annual Federal Tax Return.

There is yet another tax you must pay on your own: the Federal Unemployment Tax, or FUTA. This pays unemployment compensation to workers that lose their jobs. Employees don’t pay this at all! You, the owner of the company, pay this entirely. You report it on Form 940.

You must deposit withheld income taxes and employer and employee Social Security and Medicare taxes, minus any Earned Income Credit payments, by depositing electronically or delivering a check, money order, or cash to a banking institution that is an authorized depository for federal taxes, or by using the electronic federal tax payment system available on the Internet at the IRS’s website. It is discussed in great detail in Publication 15, under the How to Deposit section. This is one thing the IRS makes it easy to do—pay them!

You also must prepare a Form W2 each year, on the last day of February for paper forms and March 31 for electronic forms. You can do this online using the Social Security Administration’s online W2 filing system (www.socialsecurity. gov/employer).

4. Vehicles

This consideration is more pertinent if your new venture is service based, but even product-based businesses could be affected.

Rehashing an earlier example, if your idea is for a landscaping business, even if you are planning on being a sole proprietor, you will likely need a truck, and perhaps a trailer. If you are going to employ a crew (or more than one), you may even be considering a “fleet” of trucks. There are many aspects to this that need to be considered.

First, if you already own a truck, and you are planning on only using your personal vehicle, you will be allowed certain tax advantages. Similarly, if you don’t own a truck (or opt not to use your own vehicle), and you want to buy or lease a “work truck,” you will be eligible for some different and/or additional tax benefits. For example, if you lease a truck, your lease payment now becomes a business expense, as do your insurance payments and the costs of fuel and maintenance. You will not necessarily be eligible for the same tax advantages if you are using your own personal vehicle. You will need to consult with an accountant, not merely a tax preparer, for an interpretation of the full letter of the law. It is advisable to consult with a tax professional before making this decision.

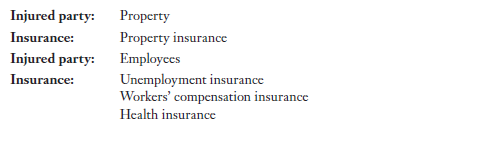

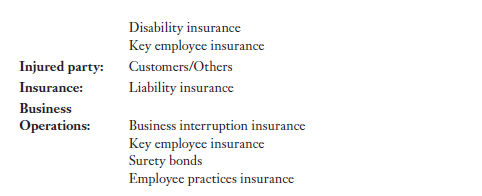

5. Insurance

I don’t mean only healthcare insurance (as I discuss this in the next section), but the other types that are often not considered, and which generally fall under the main category of “business insurance.” These include professional liability, business liability, general liability, umbrella liability, workers’ compensation, etc.

Here’s a quick breakdown, based on an injured party and insurance plans that cover the injured party:

If you’re feeling a bit overwhelmed, you’re not alone. Insurance is often overlooked for this simple reason. Here is a bit of a further breakdown from Microsoft’s website, which you can read for yourself at www.microsoft.com/ smallbusiness/resources/finance/business-insurance/protect-your-business-7- types-of-insurance-coverage.aspx:

Business owner coverage. Otherwise known as “catch-all” coverage, business owner insurance provides damage protection from fire and other mishaps. Owner coverage also offers a degree of liability protection.

Property insurance. This can augment the property coverage offered by business owner insurance. Property insurance covers damage to the building that houses your business, as well as to items inside, such as furniture and inventory.

Liability insurance. In our litigation-looped society, this may be as important a form of coverage as you can get. It covers damage to property or injuries suffered by someone else for which you are held responsible. This can take in a range of disasters, from the postal worker who sues you for a dog bite incurred during a delivery to your home business to the clumsy customer who scorches himself after you make your complimentary coffee just too darn hot.

Product liability insurance. You might want this form of coverage if you make a product that could conceivably harm someone else. For instance, catering businesses worried about some dicey-looking truffles or Brie would do well to tack on this coverage.

Errors and omissions insurance. This coverage is particularly important for service-based businesses, offering protection should you make a mistake or neglect to do something that causes a customer or client some harm. A good example is doctor’s medical malpractice insurance, which practicing physicians are required to carry.

Business income insurance. This is disability coverage for your business. It ensures you get paid if you lose income as a result of damage that temporarily shuts down or limits your business.

Automobile insurance. This last item should come as no great surprise. If your business uses cars or trucks in some manner, you have to have this type of insurance for collision and liability coverage. (Wuorio, Microsoft, 2008, retrieved from www.microsoft.com/ smallbusiness/resources/finance/business-insurance/protect-your- business-7-types-of-insurance-coverage.aspx)

Other types of insurance may be necessary or unique to your particular business. For instance, a book author or consultant may want to carry a policy that will protect them from libel, plagiarism, or negligence lawsuits. For professionals in the medical field or legal field, professional liability or malpractice insurance is important. The cost of insurance can have a significant impact on your bottom line, so find out what you really need to be protected and what your umbrella policy covers.

One thing that should be clear from this section is that you should never, ever settle for insurance you know to be inadequate, such as $300,000 in property insurance for a shop worth well over half a million dollars. You need to find a good insurance agent who you can trust, and make sure that he or she helps you get the right type of insurance plan(s) for your particular needs. Spend some time in choosing your agent. You need someone you can be comfortable with on a long-term basis—someone who will advise you well so that you can spend your time on your business, not worrying about the fine print of the coverage.

6. Healthcare

Ah, healthcare. Although mentioned in the previous section, it can get so confusing and is so often misunderstood, I’m devoting a section to it all on its own.

We hear companies complain all the time about how expensive it is to provide healthcare. We already ran through the costs for individuals and to insure your own family, but what about employees?

The price will depend on which state you live in, how healthy your employees are, and how many people you are employing, among other things. Allied Quotes at www.alliedquotes.com provides small business health insurance quotes, so you can check them out. Shop around—you will be amazed at how drastically different prices are.

You should know that health insurance, in general, is the most expensive employer-paid benefit. Many companies are cutting back by either providing lower quality service or increasing co-pays or both. The cost of healthcare is rising at a rate nearly twice that of inflation. Most small businesses in America don’t provide healthcare. For instance, in California, full time workers at small businesses account for over 20 percent of the uninsured. As of April 2008, more than half (56 percent) of all small businesses don’t offer healthcare because of the costs (SurePayroll Survey at www.surepayroll.com/spsite/press/releases/2008/ release041608.asp). It is also important to note that you do not provide healthcare to contractors. One way many employers are handling the healthcare issue is to give a self-insured healthcare credit to employees, requiring them to buy a plan and helping them offset the cost with a check each month.

Source: Babb Danielle (2009), The Accidental Startup: How to Realize Your True Potential by Becoming Your Own Boss. Alpha.

I wanted to thank you for this great read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post…