The degree of vertical, lateral, conglomerate or international integration reflects the firm’s strategic development. Another important feature of the firm is its internal administrative structure. In Chapter 6, we investigated the incentive properties of simple hierarchies, but we did not consider in what ways administrative systems might differ and whether any differences between firms might be explicable using the framework of transactions costs. Just as, at the beginning of Chapter 6, it was to the literature on management science that we turned for the early analysis of hierarchies, so it is to the business history literature that we must refer for the first attempts to analyse developments of business structure and to consider possible links between changes in structure and changes in strategy.

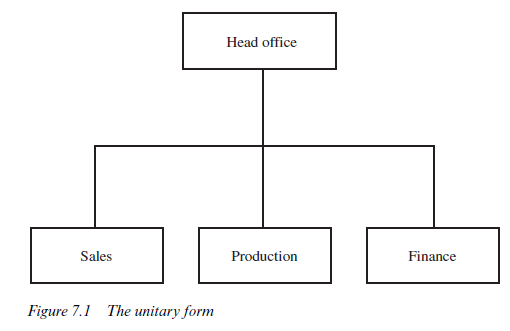

Chandler (1977) considers the impact of the railroad and the telegraph on business organisation in the United States during the nineteenth century. Although economic historians have hardly overlooked the importance of the railroad, the purely administrative achievement which they represented is not something that has been emphasised. Chandler points out that before the 1840s there were no business hierarchies in the United States and no middle managers. A railroad, however, requires a relatively complex administration to undertake the function of scheduling the trains, contracting for fuel and other supplies, maintaining rolling stock and track, selling tickets to passengers or arranging for the carriage of freight and so forth. In short, ‘the operational requirements of the railroads demanded the creation of the first administrative hierarchies in American business’ (p. 87). The typical administrative solution adopted during the nineteenth century, both in the US and in the UK, to the problems encountered as the scale of operations grew was the so called ‘functional’ or ‘unitary’ (U)- form. Although the scale of business enterprise developed rapidly, its scope remained limited. The improvements in communication brought about by the railroad and telegraph encouraged forward vertical integration into wholesaling for some branded goods, and even into retailing with the development of ‘new complex, high priced machines that required specialised marketing services – demonstration, installation, consumer credit, aftersales service and repair’ (p. 288); but the typical firm was not highly diversified and the U-form was the standard corporate structure.

Figure 7.1 illustrates the structure of a U-form enterprise. It is centralised and divided into departments which specialise in certain enterprisewide functions. For illustrative purposes, the functions identified are the conventional production, sales and finance; but we might also have added other possible functions depending upon the character of the enterprise, such as research and development, personnel and distribution. This U- form structure reflects the advantages of arranging both for managers to specialise in the problems of a particular function and for communication to be established mainly along functional lines. Production managers communicate primarily with other production workers and, for the most part, do not require detailed information about finance or marketing. Given the bounds on the individual’s information-processing capacity, each manager is left to concentrate on specific links that are expected to be most important for his or her particular purpose or function.

For enterprises with a limited scope, this system had (and has) definite advantages. Problems were encountered only when the firm began to undertake an increasing variety of activities and operate in many different geographical locations. The production and marketing problems arising in the field of one product may have very little connection with the production and marketing problems arising in another. In consequence, functional managers begin to become overloaded, attempting to make sense of flows of information which do not have many links between them. A firm manufacturing products such as shampoo, hair dyes and ethical drugs may find, for example, that the sales effort needs to be ‘divisionalised’. Ethical drugs may be marketed by visits to doctors and hospitals by a specialised staff of trained representatives. Shampoo requires large-scale advertising and may be sold through thousands of retail outlets. The same management team will find it difficult to cope with the problems of both sectors simultaneously.

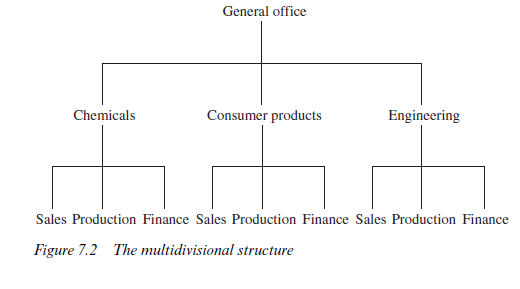

The gradually extending scope of the firm during the 1920s and 1930s in the United States led to experiments with different administrative structures and ultimately to what is now termed the multidivisional or M-form. Chandler traces these developments to a few major firms, such as Du Pont and General Motors. The innovation consisted of a set of ‘divisions’ based upon products or geographical areas, with a management organised within each division on functional lines to take responsibility for short-run operational decisions. Over these divisions was a ‘general office’ with the task of planning long-term strategy and monitoring divisional performance. Figure 7.2 illustrates the ‘pure’ case of the multidivisional structure in the context of the ‘conglomerate’. Many intermediate cases could be envisaged, of course, and it would be a mistake to consider the business history of the last seventy years simply as comprising the general gradual adoption of the ‘superior’ M-form of organisation. The M-form structure is better adapted than the U-form to a particular type of strategic development, especially conglomerate and multinational expansion, and the diversified corporation could not have reached the stage that it has without this organisational innovation, but firms adopting a more specialised strategy will not necessarily be divisionalised, or may adopt a hybrid organisational form.

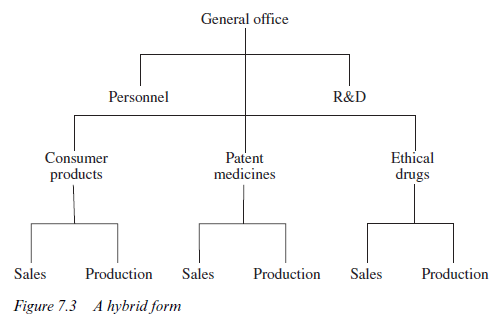

Underlying the choice of organisational structure are the same considerations which have proved important throughout this book. Information must be collected and deciphered, responses put into effect, and inputs policed. If information about the market in hair dyes, shampoos, setting lotions and the like is jointly produced, it is reasonable to prevent duplication and to attach responsibility for these products to a single office. On the other hand there may be almost no connection between the market in shampoo and that in cough mixture and even less with drugs which can be obtained only from a doctor. In these circumstances, sales might be divisionalised into consumer products, patent medicines and ethical drugs. Research and development, on the other hand, might not be divisionalised and serve the entire organisation, depending upon perceptions about possible links between research into cough mixture and other drugs. Figure 7.3 illustrates the corporate structure of an entirely imaginary corporation, specialising in chemical products that are all more or less related to ‘personal health’. If it were the case that the same production lines could be used to make and pack shampoo as could make and pack cough mixture, production would not be controlled by the divisions but would become ‘functionalised’, and the company would become increasingly U-form.

Economies in the collection and use of information therefore represent an important determinant of organisational structure. Kay (1982, 1983) presents an analysis of structure based squarely on informational links: ‘Wherever a potential link exists it may give rise to a potential economy; for example by facilitating specialisation and division of labour, or by improved exploitation of an indivisible resource’ (1984, p.95). Information which may have consequences for a number of different activities is just such an ‘indivisible’ resource. Communicating information to others can present severe problems (a factor which will be of great importance in section 6), and this leads to the boundaries between decision units being drawn ‘to minimise necessary exchanges of information’ (p.102). ‘Strategy thus determines structure; the extent and content of links dictate the appropriate form of internal organisation’ (p. 103). In the context of the large, complex corporation, the M-form, in Williamson’s words ‘served both to economise on bounded rationality and attenuate opportunism’ (1981, p. 1556). Kay (1983, Ch. 6) concentrates on information-handling economies and bounded rationality; problems that would exist even in the absence of opportunism, though Williamson’s reference to opportunism reminds us that corporate structure will also affect the ability to police inputs.

Because the staff at the general office are relieved of day-to-day operational responsibilities, much of their time is spent in considering strategic alternatives and monitoring the divisions. Two significant theoretical propositions have flowed from this observation.

- If the general office is seen as charting the overall progress of the corporation, it will have control over investment resources, which it will allocate to the various divisions. In Chapter 6, we considered Williamson’s idea of the firm as an ‘internal labour market’. Here, in Chapter 7, we come across the idea of the firm as an ‘internal capital market’. In both instances, the words ‘allocation mechanism’ might be more appropriate than the word ‘market’, since the whole point is that pure market forms of contract are superseded by ‘non-market’ forms. The terminology, however, is now quite well established. This idea of the firm as a response to transactions costs in the capital market will be considered in greater detail in sections 4 and 6.

- The existence of a group of general managers monitoring the divisions may increase the efficiency of operations and induce greater effort. This has been termed the ‘M-form hypothesis’. Organisation along M-form lines ‘favours goal pursuit and least cost behaviour more nearly associated with the neoclassical profit maximisation hypothesis than does the U-form organisational alternative’ (Williamson, 1975, p. 150). The M-form represents a more efficient monitoring environment and the gains, it is argued, will be reflected in the profitability of the firms which adopt it. This hypothesis has stimulated a number of empirical studies. Armour and Teece (1978), for example, studied a sample of petroleum firms covering the period 1955-73 and found a positive relationship between M-form structure and profitability ‘during the period in which the M-form innovation was being diffused’ (p. 106). In the period 1969-73, however, differential performance between M-form organisation and other forms was not observed and the authors inferred that ‘the sample firms were, in general, appropriately organised’ (p. 118). Thus, there is no assumption that M-form organisations are more efficient under all circumstances, but merely that for certain types of firm the M-form innovation was profitable. Over time, imitation reduces the profits accruing to the innovating firms.

Another study by Teece (1981) covered a wider range of industrial activities. It involved identifying the first firm in an industry (in the case of conglomerate enterprise this is, of course, not an easy concept to define) to adopt the M-form of organisation. This firm was tagged ‘the leading firm’ and its performance was compared with a second firm ‘the control firm’, as close to the leading firm as possible in terms of product range and size, which adopted the M-form later. Performance was compared in two time periods. In the first, only the leading firm was organised in an M-form. In the second, both firms were M-form. The economic hypothesis was that the ‘control’ firm would improve its performance relative to the ‘leading’ firm in the second period. Two statistical tests rejected the ‘null hypothesis’ that there was no effect on performance of organisational form (that is, that the probability of observing an ‘improvement’ in the second period was the same as the probability of observing a ‘deterioration’ on the part of the ‘control’ firm).4

In the UK, adoption of the M-form took place later than in the USA (Channon, 1973). ICI was evolving a divisionalised structure as early as the 1930s (Hannah, 1983a, pp.81-5) and this was fully established by the mid- 1950s, described in such textbooks as Edwards and Townsend (1967, p. 67). This experience, however, was not typical. Just as the UK lagged by several decades in the merger movement which established the framework of the ‘corporate economy’ at the end of the nineteenth century and the very beginning of the twentieth century in the USA, there was a similar lag in the development of managerial structures to cope. Between the two World Wars, many firms in the UK were ‘loosely run confederations of subsidiaries with little central control’ (Hannah, 1983a, p. 87). As was reported in Chapter 4, Chandler identifies family management and the absence of a managerial class as reasons for UK backwardness. In the USA, adoption of the M-form of organisation and the rapid development of conglomerate and multinational enterprise were associated with the 1940s and 1950s. In the UK (and other European countries), these changes appear to have been delayed until the 1960s and 1970s. When they did arrive, the evidence of studies by Steer and Cable (1978) and Thompson (1981) is that the organisational changes had substantial effects consistent with the M-form hypothesis.

Source: Ricketts Martin (2002), The Economics of Business Enterprise: An Introduction to Economic Organisation and the Theory of the Firm, Edward Elgar Pub; 3rd edition.

naturally like your web site but you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I find it very bothersome to tell the reality nevertheless I¦ll surely come back again.