1. About the Firm

LG Electronics (LG) is the second largest Korean Chaebol in consumer electronics after Samsung. Established in 1958, LG was originally known under the brand Lucky Goldstar. During the 1960s, LG produced Korea’s first radios, television sets, refrigerators, washing machines, and air conditioners. In 1995, renamed LG Electronics, the Korean conglomerate acquired the US-based enterprise Zenith. In 2008, LG introduced a new global brand identity: ‘stylish design and smart technology in products that fit our consumers’ lives’ (LG Electronics 2005a, 2005b, 2009). During the last two decades, LG Electronics developed successfully, expanded worldwide, and became a serious competitor in the electronics business. However, the aggressive expansion was financed to a large extent by loans, which resulted in a critical debt-to-equity ratio. As a result of the financial crisis in Asia at the end of the 1990s, LG Electronics faced severe financial difficulties and needed to find external investors (Glowik 2007b; LG Electronics 2008).

At that time, the traditional and largest European-based electronics company, the Royal Dutch Philips from the Netherlands, was technologically already behind its Korean competitor in television flat panel manufacturing. Philips had a very reputable image with enormous brand recognition among European customers and had a large European sales network, which were the firm’s most valuable resource assets. The 1990s was a decade of organizational changes for Philips. The company carried out a major restructuring program, simplifying its organizational structure and reducing the number of business areas (Philips 2008). In September 2006, Philips sold 80.1 percent of its semiconductor business to a consortium of private equity partners. This laid the foundation for a new independent semiconductor company, called NXP. In September 2007, Philips communicated its Vision 2010 strategic plan to further grow the company with increased profitability targets. As part of Vision 2010, the organizational structure was simplified on January 1, 2008, by forming three sectors: Healthcare, Lighting, and Consumer Lifestyle. With a massive advertising campaign to unveil its new brand promise of ‘sense and simplicity,’ the company confirmed its dedication to offering consumers around the world products that are advanced; easy to use; and, above all, designed to meet their needs (Philips 2008).

2. The Foundation of the First International Joint Venture Between LG Electronics and Philips Named PhilipsLCD

In August 1999, the management of Philips took the chance to overcome its technological drawback in flat panel display technologies and decided to invest in LG Electronics. Philips paid USD 1.6 billion to LG Electronics and reserved 50 percent of the shares of the newly established joint venture, LG.PhilipsLCD. The partnership aimed for world leadership in the flat display television set industry. The capital investment was carried out so that Phillips purchased new stock (common shares) against payment to LG Electronics, which kept 98.8 percent of the subsidiary LG LCD shares it held before the transaction was completed (LG.PhilipsLCD 2005a, 2005b).

The joint venture with LG was not the first time Philips had tried to get into the LCD panel business through a partnership with another firm. Several years before, Philips experimented with developing its own production facilities with limited success. In 1997, Philips attempted to join forces and establish a joint venture with Hosiden Co., Kobe, Japan, a second-tier Japanese LCD manufacturer (Kovar 1999). However, the joint venture failed and caused losses that reached more than USD 100 million a year (Bondgenoten 2001).

At the beginning, the international new venture, LG.PhilipsLCD, was managed by a board of directors composed of six members, three each from LG and Philips. According to a press release:

The alliance between LG Electronics Inc. and Philips (implemented through selling shares of LG LCD, the global electronic appliances manufacturer) is considered to have an important meaning from the perspective of competition strategy for the highly technical electronics industry, including LCDs. The alliance provides an opportunity for Korea to have absolute superiority in the leading-edge LCD industry because a synergy effect will be generated when the world-class technology of LG’s LCD is combined with the market reputation and distribution network of Philips (LG.PhilipsLCD 2001).

In other words, besides the financial investment of Philips, which helped LG survive at the peak of the financial crisis in Asia, the Korean Chaebol could make use of Philips’ exclusive brand and distribution network in Europe and America. Previously, LG’s reputation in Europe was linked with a rather cheap, imitative manufacturer’s image; and the company name, ‘Lucky Goldstar,’ was rather promoting its low-end image among European consumers.

Headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, the newly established international joint venture, LG.PhilipsLCD, operated six fabrication facilities in China and South Korea and had approximately 15,000 employees, including those in South Korea. A new production site in Poland, responsible for the manufacture of LCD modules targeting the European market, launched production in 2007 (LG.PhilipsLCD 2007a, 2007b, 2007c). LG.PhilipsLCD started to compete mainly against Samsung and Sharp in the segment that manufactures and supplies thin-film-transistor liquid crystal display (TFT-LCD) panels. The firm concentrated on TFT-LCD panels in a wide range of sizes and specifications for use in notebook computers, desktop monitors, and television sets (LG.PhilipsLCD 2008a). On September 6, 2005, LG.PhilipsLCD announced that it planned to construct a ‘back-end’ module production plant in Wroclaw, becoming the first global LCD industry player to commence such production in Europe. LG.PhilipsLCD considered building a production plant by 2011 with an annual capacity of 11 million units and an investment volume total of 429 million euros. The manufacture of the LCD module began in the middle of 2007, when the construction of the first batch of module lines was completed with an annual capacity of 3 million units (LG.PhilipsLCD 2006a, 2006c). As the vice chairman and CEO of LG.PhilipsLCD, Bon Joon Koo, commented,

Our planned production facility in Poland is an important step for LG.PhilipsLCD, as we establish our manufacturing expertise in the geographic center of Europe. With this first major factory outside of Asia, LG.PhilipsLCD will better serve the rapidly growing European LCD TV market. As we implement our strategic plan for the future, we are proud to broaden the reach of our industry-leading LCD technology and expand our customer intimacy as we bring our products closer to our customers. We are grateful to the Polish government and the city of Wroclaw for their support and cooperation in this great partnership (LG.PhilipsLCD 2006c).

LG.PhilipsLCD relied on a worldwide manufacturing network. Major LCD display production plants were located in Asia and Europe, which provided various advantages in terms of manufacturing costs and logistics because of proximity to its regional markets (compare Figure 4.28).

Global sales were organized by LG.PhilipsLCD, mainly through three distribution clusters in Europe, America, and Asia, which served as a further strength relative to its competitors (compare Figure 4.28).

The investment of LG.PhilipsLCD in Kobierzyce, near Wroclaw, in 2005 generated further market entry activities through direct foreign investment in Poland. The Japanese electronics enterprise Toshiba, for example, decided to set up a Polish subsidiary, assembling LCD TVs in Kobierzyce as well. Toshiba also operated an LCD factory in Plymouth, UK. The new Polish plant was scheduled to start operation by mid-2008. About 1,000 employees would manufacture between 1.5 and 2 million 32-inch and larger TVs annually (Johnston 2006; LG.PhilipsLCD 2007c). Toshiba’s annual production capacity of flat panel TVs in Europe, counting both UK and Polish output, reached around 3 million units by 2009. Toshiba’s factory procured large quantities of its LCD panels from the Dutch-Korean joint venture LG.PhilipsLCD. Toshiba invested 19.9 percent interest in the LG.PhilipsLCD plant in Poland. The developing industry cluster initiated the market entry of Korean component suppliers (‘follow the customer’ phenomenon). Various Korean firms decided to enter the Polish market and invested near the LG.Philips plant. Poland was becoming an important industry cluster in terms of vertically integrated LCD television set manufacturing outside Asia, which at that time was unique. From Poland, the module supply of LG.PhilipsLCD to other television set assemblers located in Europe was organized as Figure 4.30 illustrates (Johnston 2006; LG.PhilipsLCD 2007c).

In the years following the founding, LG.PhilipsLCD established various bilateral relationships with other firms doing business in consumer electronics. Stable supplier-customer relationships that secure economies of scale as well as the wish to develop a technological leadership positioning in the LCD business were the main incentives for seeking relationships for LG.PhilipsLCD. The networking activities of LG.PhilipsLCD led to the introduction of other partner firms with further distribution channels, competencies, and technological knowledge to the LG.Philips relationship network (compare Figure 4.31).

Despite a loss in 2001, net income increased in the years following the venture’s founding and reached a peak of around USD 1.5 billion in 2004. In 2006, more LCD TVs were sold in Europe than cathode-ray tube TVs, for the first time in history. Market forecasts were promising. Overall, the global LCD business developed well, and LG.Philips was able to reap the rewards of it. In the following years net sales and net income progressively developed because of the increasing LCD TV market demand. The joint venture delivered positive results in terms of the net sales and also net income. The data below illustrate the financial development of the joint venture (LG.PhilipsLCD 2003, 2006b, 2008b).

3. Philips Reduces its Stake in LG.PhilipsLCD and Says Good-Bye

On March 3, 2008, LG.PhilipsLCD changed the name of the firm. The world’s second-largest manufacturer of LCDs, which began as a joint venture between South Korea’s LG Electronics Inc. and Philips in 1999, was renamed LG Display Corporation nine years later. Despite the promising financial development of the international joint venture, Philips finally decided to terminate its engagement. On the one hand, Philips doubted the future of the LCD business due to competitive forces. On the other hand, Philips was in need of money in order to finance their new ambitions in the medical devices and healthcare sector. As a result, the Philips name disappeared from the title of the joint venture as result of the stepwise reduction in shares held by Philips. In October 2007, Philips reduced its stake from 32.9 to 19.9 percent, followed by a further reduction in March 2008 to 13.2 percent. As per December 31, 2007, LG Electronics, LG.Philips’ largest shareholder, held a 37.9 percent stake. Domestic (Korean) shareholders held 25.3 percent, and overseas investors and others held 16.9 percent (LG.PhilipsLCD, 2008c). In April 2008, Mr. Young Soo Kwon, CEO of LG Display, announced,

Last quarter was a notable quarter for us. Our performance was encouraging despite the seasonally slow market conditions. In addition, we have changed our corporate name from LG.PhilipsLCD Co., Ltd., to LG Display Co., Ltd., and will transition into a single representative director’s organization at the annual general meeting in accordance with the change in corporate governance following the reduction of Philips’ equity. The new name reflects our intention to expand our business scope and diversify the business model for sustainable growth in the future. While there were changes in our corporate governance, we remain committed to maintaining our integrity and being transparent and consistent, accompanied by our competent directors on the board (LG.PhilipsLCD 2008c).

From this time onwards, LG Display Co., headquartered in Seoul, South Korea, concentrated its research and development in Anyang (South Korea) and maintained major module factories in Paju and Gumi (South Korea). In China, the firm established factories in Nanjing and Guangzhou. The one and only European module assembly line remains in Wroclaw, Poland.

Philips announced in February 2008 that it is looking to outsource manufacturing for 70 percent of its LCD TVs (in 2006 nearly 60 percent). The company expected to ship 14 million LCD TVs in 2008, with about 10 million units outsourced (Digitimes.com 2008). In other words, Philips will further reduce its technological and manufacturing involvement in the television set business, taking the increased risk of losing know-how. According to the firm’s strategic plan, Philips will strengthen its activities in other business segments, such as lighting and healthcare, in order to be prepared for future markets (Emphasize Emerging Markets 2007).

4. The Foundation of the Second International Joint Venture Between LG Electronics and Philips Named Philips Displays- This Time Everything Will be Better?!

In Amsterdam, on June 11,2001, Gerard Kleisterlee, president and chief executive officer of Royal Philips Electronics, and John Koo, vice chairman and CEO of LG Electronics, signed a ‘definitive agreement’ through which the two companies would merge their respective cathode ray tube (CRT) businesses into a new joint venture company. The official presentation of the new company was held on July 5,2001, in Hong Kong. The fifty-fifty joint venture in display technology concerned all CRT activities, including glass and key components. With expected annual sales of nearly USD 6 billion and approximately 36,000 employees, the new company was expected to have a global leadership position in the CRT market. Philips paid USD 1.1 to LG Electronics. At that time, the joint venture held 25 percent of the global market share and ranked ahead of Samsung SDI in the CRT business. The following complementary strengths and synergy potentials of the merged entities were mentioned by both parties’ management in an enthusiastic manner (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2001a, 2001b):

- Philips’s leadership in television tubes and LG’s leadership in monitor tubes

- LG’s geographical leadership in Asia and Philips’ brand reputation and distribution network in Europe, China, and America

- LG’s industrial and manufacturing expertise and Philips’ global marketing and technological innovation. Further benefits were expected in the areas of purchasing as well as research and development through combining resources and economies of scale effects (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2001b)

Under the terms of the agreement, LG and Philips had equal control of the joint venture. The new company was legally established in the Netherlands, with operational headquarters in Hong Kong. Philippe Combes, former CEO of Philips Display Components, was appointed to lead the joint venture (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2001a, 2001b).

Synergies of joint venture operations below expectations, but why?

The television set market dramatically changed in 2004. While the demand for conventional cathode ray tubes went down, LCD and plasma sales increased. LCD replaced conventional television set sales in Europe. Nevertheless, even in 2005, LG.Philips Displays still pronounced in a press release the bright future of conventional television sets and that the cathode ray technology would remain a dominant force in display technology, for example, through the introduction of ‘slim tubes’ (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005a, 2005d). The venture management was totally wrong when it made such a forecast. Just two years later, in 2007, 26 million LCD sets were sold in Europe compared to only 10 million CRT-based units (DisplaySearch 2008; GfK 2007). From 2010 onwards it was even hard to find conventional, bulky CRT-based TVs. Everybody wanted to have ‘flat and light.’ CRT manufacturers in general, among them LG.Philips Displays, faced increasing price pressure, particularly in highly competitive markets such as Europe. During the course of an increasing risk of running overcapacities, the culturally biased management behavior became increasingly obvious in the Korean-Dutch joint venture. Mr. David Kang, a manager of LG Electronics, explained his joint venture work experience to me,

There is a considerably different understanding among Western managers. They insist always on profits, the earlier the better. But our view is different and more long-term oriented. We enter the market with reasonable, well, let’s say with low prices. We may even have a loss. But what is more important? If we become the market leader, one day our products will set the standards. Then we will drive the market and its prices. From my point of view, these contrasting time horizons are one of the main reasons why joint ventures of Western and Korean companies fail (Glowik 2007a).

Concerning different work attitudes and language barriers, Mr. Kang further commented,

When we had a problem with the customer, for example, it was sometimes hard to find a Western manager when it happened out of the ordinary daily working time. We Koreans cannot understand such customer treatment. For the Europeans, it seems more important to arrange the time with their private families. We Koreans work hard; we have a lot fewer holidays, but the Philips people had 2.5 times higher salaries than we had. How can a joint venture run like this in the long term? Moreover, I have to say, we had a communication problem. English was selected as the company language, but Koreans have weaknesses communicating in English (Glowik 2007a).

The European view of the joint venture was different. A former senior manager at LG.Philips Displays, who preferred to remain anonymous, commented about the working atmosphere in the international joint venture like this,

When we (Philips) had a meeting with LG people, sometimes they kept silent the whole time. Later, we recognized the Koreans arranged a separate meeting among themselves, where they discussed and fundamental decisions were made…without us. Moreover, I think the Koreans had very effective conversations among themselves in the ‘smoker’s room’ more than during official meetings with us. It is hard to cooperate and get access to them. The Korean community is rather a closed shop (Glowik 2004).

Just two years after the establishment of the joint venture, on May 22,2003, LG.Philips Displays announced the closure of its European production plants in Newport, Wales, and Southport, England, and that the management had started consultations with employees and trade union representatives (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005b, 2005c). The corresponding press release said,

The decision is based on business and economic conditions, which are characterized by an increasingly competitive and consolidating industry. The company’s plant at Newport in South Wales produces color display tubes (CDT) for monitors and color picture tubes (CPT) for televisions as well as deflection yokes. A sharp decline in the market for CDTs due to increasing competition from other display technologies also supplying products for use in computer monitors and severe downward pressure on prices for CDT and CPT are the primary reasons for the closure (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005c).

Phil Styles, general manager of manufacturing at Newport, commented,

The decision to close was made with great regret and is based solely on the continuing adverse business situation. It in no way reflects on the performance of the employees at the plant, who have worked hard and demonstrated considerable commitment over these past five years (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005c).

Just a couple of months later, on December 2, 2003, LG.Philips Displays announced a decision to further restructure its industrial production infrastructure in Europe. As announced by the management,

The measures, in line with the company’s continuous drive for optimizing business performance, are necessary to remain competitive in a mature and consolidating industry. As a consequence, the company’s cathode ray tube plants in Aachen, Germany, and a glass factory in Simonstone, UK, will be shut down. At all other sites in Europe, cost reduction will be realized by further optimizing the production infrastructure (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005e, 2005f).

In the following years, LG.Philips continued the final closing process, mainly of its European facilities. On March 2,2005, LG.Philips Displays published the closure of its plant at Durham in Northeast England. As was stated in the press release,

Crippling price erosion and a shift in demand from Europe to Asia Pacific are the main reasons for the decision, which has been made with great regret. Consultations with employees and trade union representatives have begun. Production is expected to cease towards the end of July 2005 and will result in the loss of 761 jobs (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005b).

Finally, in October 2005, Philips announced that it would stop television set manufacturing for the European market, which affected its major supplier LG.Philips Displays and particularly its brand new factory in Hran- ice, Czech Republic, as well as its R&D and manufacturing facilities in Angers, France. Nevertheless, major production operations in Asia and some in Brazil, representing 85 percent of total manufacturing capacity, as well as minor European component suppliers (Stadskanaal and Sittard, the Netherlands, and Blackburn, United Kingdom) continued activities (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005e, 2006, 2007a).

Three months later, on January 27,2006, LG.Philips Displays Holding B. V. announced that due to worsening conditions in the cathode ray tube marketplace and unsustainable debt, the holding companies, as well as one of the Dutch subsidiaries (LG.Philips Displays Netherlands B. V.) and its remaining legal German subsidiary in Aachen, Germany, had all filed for insolvency protection. The holding company of LG.Philips Displays in Hong Kong also announced that it would not be able to provide further financial support to certain loss-making subsidiaries (in Europe) because it had been unable to obtain sustainable new or additional funding. As a result, approximately 350 employees at the company’s operations in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, and 400 employees in Aachen, Germany, were dismissed (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2006). Concerning the insolvency filings, LG.Philips Displays headquarters in Hong Kong officially declared in a corresponding press release,

Over the past year, LG.Philips Displays and other CRT manufacturers have seen an unprecedented decline in the market for CRTs, especially in Europe. At the same time, the demand for new flat panel televisions, including liquid crystal display (LCD) and plasma televisions, has surged dramatically as these alternatives have dropped in price and become cost competitive faster than anticipated. Although demand for CRTs has dropped precipitously in mature markets, global demand for CRTs remains strong, especially in emerging markets. LG.Philips Displays has been in extensive discussions with the company’s financiers and parent companies, Philips and LG Electronics, over the past several months to explore financial solutions to the market challenges, especially in Europe (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2006).

The president and CEO of LG.Philips Displays, Korean native, J. I. Son, commented,

We deeply regret this outcome and the painful impact these filings will have on our valued employees and the communities that have supported us over the years. Unfortunately, market conditions and our financial situation have made this very difficult decision unavoidable. Having explored all possible restructuring options, we really have no choice but to take these actions. We are working to maintain employment for our remaining employees through our ongoing operations (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2006).

In the course of its retrenchment strategy, additional subsidiaries of LG.Philips Displays in France, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Mexico, and the US were liquidated. LG.Philips Displays emphasized that its plants in Brazil, China, Indonesia, South Korea, and Poland (component supplier) were, in principle, unaffected. The company’s factories in the United Kingdom (Blackburn) and the Netherlands (Stadskanaal and Sittard, with support from some employees in Eindhoven) were economically viable and were expected to continue production, for which LG.Philips Displays would seek support and approval from the Dutch trustee and supervisory judge (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2005e, 2006).

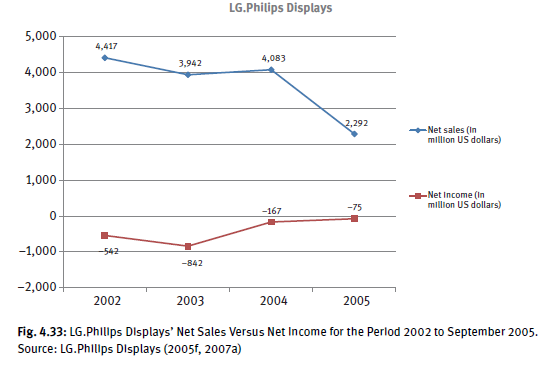

In fact, the LG.Philips Displays joint venture operations resulted in a loss just after the firm’s foundation. The financial situation could not recover in the following years. What are the reasons? Contrary to optimistic forecasts by the joint venture parents Philips and LG Electronics, the European television set cathode ray tube market declined. CRT technology had reached the end of its product life-cycle and had been replaced by flat panel technologies. Consequently, competition had become more and more price focused. The remaining tube supplying manufacturers in Europe, such as large firms like Samsung, Thomson, and Panasonic, but also small competitors like Ekranas (Lithuania) and Tesla (Czech Republic) operating in niche markets, were seriously competing for survival. Additionally, Chinese cathode ray tube manufacturers increased their shipments to Europe and worsened the attractiveness of the market. In parallel, the venture partners from contrasting cultural backgrounds could not solve internal communication problems, which had a negative impact on performance as illustrated in Figure 4.33 (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2001a 2007b).

In 2001, when the joint venture with LG Electronics was established, the television set business unit of Philips had a turnover of USD 3 billion, ran twelve cathode ray tube production sites with 24,000 workers worldwide, and reached a profit of USD 157 million (Bondgenoten 2001). Just a couple of years later, the former European market leader in consumer electronics, Philips, had disappeared with the joint venture bankruptcy and simultaneously disappeared from the cathode ray tube television set business (The Inquirer 2006).

5. Philips Displays Gets a New Name

Effective on April 1, 2007, LG.Philips Displays changed its name to LP Displays. The corresponding press release by the top management said,

The new name and stylized logo are designed to reflect its new corporate status while saluting its roots as a joint venture between LG Electronics and Royal Philips Electronics. At the same time, it reinforces continuity in LP Displays’ position as one of the world’s leading global suppliers of picture tubes used for television sets and computer monitors. The new name and the logo act as an important step forward for LP Displays and reflect the management and financial stakeholders’ confidence in both the future of the company and the CRT business (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2007c).

LP Displays continued to focus its business on high-performance CRTs and a growing demand for its ‘SuperSlim’ and ‘UltraSlim’ CRTs, particularly in emerging markets. The global demand for CRTs was expected to remain strong. LP Displays’ president and CEO, Mr. Jeong IL Son, commented,

Of the countries with the largest populations, the majority will be CRT customers for the foreseeable future. Markets in Asia and South America offer the company an exciting challenge going forward, and the ’UltraSlim’ and ‘SuperSlim’ series provide LP Displays the competitive advantage it needs to capture this tremendous opportunity (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2007c).

LP Displays’ management team remained in Hong Kong under the leadership of Mr. Son. The company continued to serve its global markets from its plants in Brazil, China, Indonesia, and South Korea and from its minor component operations in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. LP Displays continued to employ around 11,000 people worldwide. The company’s new name and logo reflected the change in ownership structure. Dutch representatives disappeared completely from the firm, which was originally established in 2001 as a fifty-fifty joint venture with a payment of USD 1.1 billion by Philips. A couple of years later, the top management consisted of Korean managers only: Mr. Jeong IL Son, president and chief executive officer; Mr. Deok Sik Moon, chief financial officer and deputy chief executive officer; Mr. J. M. Park, chief sales officer; and Mr. Soo Dyeog Han, executive vice president of New Business Development (LG.PhilipsDisplays 2007c).

6. What Happened Next to the International Joint Venture Terminations?

Without the financial involvement of Philips, it is questionable whether LG could have recovered and developed successfully after the Asian financial crisis as they have done in recent years. On the one hand, the management of Philips underestimated the sharp decline in conventional cathode ray tube TV demand when the company decided to invest in the joint venture with LG Electronics. On the other hand, the Philips’ management obviously did not foresee that flat TV technology would drive the business at least for the next decade when they decided to leave the LG.PhilipsLCD joint venture in 2008. Meanwhile, the European joint venture partner, Philips, lost its vertical manufacturing integration in the consumer electronics business. Today we can still buy consumer electronics products such as television sets, audio, and others where the Philips brand is labeled on the outside of the product. Most customers believe the consumer electronic product is from Philips. However, the reality is that it is assembled by Taiwanese, Chinese, or other firms, usually based on a manufacturing or licensing contract against payment of loyalties to Philips.

The management of Philips did not pay too much attention to the absorptive and fast learning capabilities (compare the resource-based view) of LG Electronics’ management. LG gained valuable knowledge from Philips in terms of marketing (such as a favorable brand name and slogans for the European markets) and access to Western markets and their distributions channels. For instance, LG has changed the meaning of its initials from ‘LG = Lucky Goldstar’ to ‘LG = Life’s Good’, in order to get closer to its European customers. The strength of LG Electronics is its technology and research and development expertise. Through its new LCD module plant in Poland, the firm has been able to supply LCD modules to the LG Electronics factory in Mlawa, Poland, which does the final assembly of television sets and supplies them to the entire European market. Following the joint venture termination, LG Electronics could have significantly increased its net sales on the global markets. Net income has not increased over the years, but the Korean company has performed better than, for example, firms like Sony or Panasonic in terms of net income during the years after the joint venture termination. In 2009 net sales and net income almost doubled compared to the previous year. As illustrated in Figure 4.35 sales remains volatile between around USD 54 billion in 2014 and around USD 46 billion in 2016 and USD 55 billion in 2018. Net income has increased from half a billion US dollars in 2014 to more than USD 1.3 billion in 2017 and USD 1.2 billion in 2018 (LG Electronics 2019).

7. And the Future?

In 2019, South Korea’s LG Display Co., a sub division of LG Electronics, decided to shut down its liquid crystal display (LCD) module plant in Poland, its manufacturing base in Europe built in 2005. LG aims to move away from the ‘money-losing’ LCD business due to emerging Chinese and Taiwanese competition. Instead, LG is shifting its activities to organic light-emitting diode (OLED) display TV manufacturing (HwanJin & HaYeon 2019). LG currently operates two display manufacturing plants at home and eight in three countries overseas – five in China, one in Vietnam, and one in Poland, and the Polish manufacturing site will be sold to LG Chem before June, LG Display said. LG Chem, which already has a battery facility in Poland, will decide on what to do with the new site (HwanJin & HaYeon 2019).

Today, LG is leading the way technologically in OLED since it started supplying first OLED TV panels in 2013. They deliver OLEDs to various TV assemblers including its main competitor from Korea, Samsung, but also to Japanese competitors such as Sony and Panasonic. In 2018 the Korean company shipped 3 million units of OLED panels and plans to add 8K resolution OLED panels to its TV panel line-up from 2020 onwards. Prices and corresponding margins in the OLED market segment are higher than average TV prices. Besides the 8K modules, LG Display is developing other advanced OLEDs such as speaker-embedded Crystal Sound OLED (CSO) and Wall Paper TV, which is as thin as wallpaper, as well as rollable and with transparent displays. ‘We’re going all-out efforts to make OLED the standard type of display and LG Display will cement its position as a global leader in the display market,’ said Han Sang-Beom, vice chairman and CEO of LG Display at a press meeting in 2019 (HwanJin & HaYeon 2019). LG Display is a part of the home entertainment division (e.g., audio, video, TV, monitors) which is one out of five business divisions of LG Electronics [status: 20 November 2019] such as mobile communication (smartphones), home appliance and air solution (e.g., refrigerators, washing machines, dishwasher, vacuum cleaners, etc.), vehicle component solution (e.g., infotainment), and business solutions (e.g., energy storage) (compare Figure 4.36)

LG Electronics is making use of its core competencies by, focusing on its display technology expertise and, therefore diversifying into other related business fields such as the smartphone and automotive industries. Similar to Samsung, LG Electronics develops car infotainment devices, including monitors and navigation systems. Aside from in-vehicle infotainment, LG also offers safety, engineering, and electric vehicle solutions that target autonomous and energy-saving driving (LG Electronics 2015b). LG’s vehicle components division combines component-related business units by merging the car infotainment unit with the home entertain-ment division. LG Electronics also develops motors and batteries for electric vehicles as well as inverters and compressors (LG Electronics 2015a, 2015c). However, the home entertainment division, with its OLED products, will remain one of the most important business units where the destiny of LG Electronics probably will be decided in the coming years.

Source: Glowik Mario (2020), Market entry strategies: Internationalization theories, concepts and cases, De Gruyter Oldenbourg; 3rd edition.

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

21 Jul 2021

3 Jun 2021

21 Jul 2021