To take advantage of all the resources and practices available, good marketers adopt a formal marketing research process that follows the six steps shown in Figure 4.1. We illustrate these steps in the following situation.17

American Airlines (AA) was one of the first companies to install phone handsets on its planes. Now it’s reviewing many new ideas, especially to cater to its first-class passengers on very long flights, mainly businesspeople whose high-priced tickets pay most of the freight. Among these ideas are:

(1) ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service, (2) 124 channels of high-definition satellite cable TV, and (3) a 250-CD audio system that lets each passenger create a customized in-flight playlist. The marketing research manager was assigned to investigate how first-class passengers would rate these services, specifically ultra high-speed Wi-Fi, and how much extra they would be willing to pay. One source estimates revenues of $70 million from Wi-Fi access over 10 years if enough first-class passengers paid $25. AA could thus recover its costs in a reasonable time, given that making the connection available would cost $90,000 per plane.

1. STEP 1: DEFINE THE PROBLEM, THE DECISION ALTERNATIVES, AND THE RESEARCH OBJECTIVES

Marketing managers must be careful not to define the problem too broadly or too narrowly for the marketing researcher. A marketing manager who says “Find out everything you can about first-class air travelers’ needs” will collect a lot of unnecessary information. One who says “Find out whether enough passengers aboard a B777 flying direct between Chicago and Tokyo would pay $25 for ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service so we can break even in one year on the cost of offering this service” is taking too narrow a view of the problem.

The marketing researcher might ask, “Why does Wi-Fi have to be priced at $25 as opposed to $15, $35, or some other price? Why does American have to break even on the service, especially if it attracts new customers?” Another relevant question is, “How important is it to be first in the market, and how long can the company sustain its lead?”

The marketing manager and marketing researcher agreed to define the problem as follows: “Will offering ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service create enough incremental preference and profit to justify its cost against other service enhancements American might make?” To help design the research, management should first spell out the decisions it might face and then work backward. Suppose management outlines these decisions: (1) Should American offer ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service? (2) If so, should it offer it to first-class only or include business class and possibly economy class? (3) What price(s) should be charged? (4) On what types of planes and lengths of trips should the service be offered?

Now management and marketing researchers are ready to set specific research objectives: (1) What types of first-class passengers would respond most to ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service? (2) How many are likely to use it at different price levels? (3) How many might choose American because of this new service? (4) How much long-term goodwill will this service add to American’s image? (5) How important is ultra highspeed Wi-Fi service to first-class passengers relative to other services, such as a power plug or enhanced entertainment?

Not all research can be this specific. Some is exploratory—its goal is to identify the problem and to suggest possible solutions. Some is descriptive—it seeks to quantify demand, such as how many first-class passengers would purchase ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service at $25. Some research is causal—its purpose is to test a cause-and-effect relationship.

2. STEP 2: DEVELOP THE RESEARCH PLAN

In the second stage of marketing research we develop the most efficient plan for gathering the needed information and discover what that will cost. Suppose American made a prior estimate that launching ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service would yield a long-term profit of $50,000. If the manager believes the marketing research will lead to an improved pricing and promotional plan and a long-term profit of $90,000, he should be willing to spend up to $40,000 on this research. If the research will cost more than $40,000, it’s not worth doing.

To design a research plan, we need to make decisions about the data sources, research approaches, research instruments, sampling plan, and contact methods.

DATA SOURCES The researcher can gather secondary data, primary data, or both. Secondary data are data that were collected for another purpose and already exist somewhere. Primary data are data freshly gathered for a specific purpose or project.

Researchers usually start their investigation by examining some of the rich variety of low-cost and readily available secondary data to see whether they can partly or wholly solve the problem without collecting costly primary data. For instance, auto advertisers looking to get a better return on their online car ads might purchase a copy of a J. D. Power and Associates survey that gives insights into who buys specific brands and where advertisers can find them online.

When the needed data don’t exist or are dated or unreliable, the researcher will need to collect primary data. Most marketing research projects do include some primary-data collection.

RESEARCH APPROACHES Marketers collect primary data in five main ways: through observation, focus groups, surveys, behavioral data, and experiments.

Observational Research Researchers can gather fresh data by observing unobtrusively as customers shop or consume products. Sometimes they equip consumers with pagers and instruct them to write down or text what they’re doing whenever prompted, or they hold informal interview sessions at a cafe or bar.18 Photographs and videos can also provide a wealth of detailed information. Although privacy concerns have been expressed, some retailers are linking security cameras with software to record shopper behavior in stores. In its 1,000 retail stores, T-Mobile can track how people move around, how long they stand in front of displays, and which phones they pick up and for how long.19

Ethnographic research uses concepts and tools from anthropology and other social science disciplines to provide deep cultural understanding of how people live and work.20 The goal is to immerse the researcher into consumers’ lives to uncover unarticulated desires that might not surface in any other form of research.21 Fujitsu Laboratories, Herman Miller, Steelcase, and Xerox have embraced ethnographic research to design breakthrough products. Technology companies like IBM, Microsoft, and Hewlett-Packard use anthropologists and ethnologists working alongside systems engineers and software developers.22

Any type of firm can benefit from the deep consumer insights of ethnographic research. To boost sagging sales for its Orville Redenbacher popcorn, ConAgra spent nine months observing families at home and studying weekly diaries of how they felt about various snacks. Researchers found a key insight: the essence of popcorn was that it was a “facilitator of interaction.” Four nationwide TV ads followed with the tagline “Spending Time Together: That’s the Power of Orville Redenbacher.”23

Ethnographic research isn’t limited to consumer products. UK-based Smith & Nephew, a global medical technology business, used extensive international ethnographic research with patients and clinicians to understand the physical and emotional toll of wounds, developing ALLEVYN Life, a new wound-management dressing, in the process.24 In a business-to-business setting, a sharper focus on end users helped propel Thomson Reuters to greater financial heights.25

THOMSON REUTERS Just before it acquired Reuters, global information services giant Thomson Corporation embarked on extensive research to better understand its ultimate customers. Thomson sold to businesses and professionals in the financial, legal, tax and accounting, scientific, and health care sectors, and it wanted to know how individual brokers and investment bankers used its data, research, and other resources to make day-to-day investment decisions for clients. Segmenting the market by its end users, rather than by its corporate purchasers, and studying the way they viewed Thomson versus competitors allowed the firm to identify market segments that offered growth opportunities. Thomson then conducted surveys and “day in the life” ethnographic research on how end users did their jobs. Using an approach called “three minutes,” researchers combined observation with detailed interviews to understand what end users were doing three minutes before and after they used one of Thomson’s products. Insights from the research helped the company develop new products and make acquisitions that led to significantly higher revenue and profits in the year that followed.

The American Airlines researchers might meander around first-class lounges to hear how travelers talk about different carriers and their features or sit next to passengers on planes. They can fly on competitors’ planes to observe in-flight service.

Focus Group Research A focus group is a gathering of 6 to 10 people carefully selected for demographic, psychographic, or other considerations and convened to discuss various topics at length for a small payment. A professional moderator asks questions and probes based on the marketing managers’ agenda; the goal is to uncover consumers’ real motivations and the reasons they say and do certain things. Sessions are typically recorded, and marketing managers often observe from behind two-way mirrors. To allow more in-depth discussion, focus groups are trending smaller in size.26

Focus group research is a useful exploratory step, but researchers must avoid generalizing to the whole market because the sample is too small and is not drawn randomly. Some marketers feel this research setting is too contrived and prefer less artificial means. “Marketing Memo: Conducting Informative Focus Groups” has some practical tips to improve the quality of focus groups.

In the American Airlines research, the moderator might start with a broad question, such as “How do you feel about first-class air travel?” Questions then move to how people view the different airlines, different existing services, different proposed services, and, specifically, ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service.

Survey Research Companies undertake surveys to assess people’s knowledge, beliefs, preferences, and satisfaction and to measure these magnitudes in the general population. A company such as American Airlines might prepare its own survey instrument, or it might add questions to an omnibus survey that carries the questions of several companies at a much lower cost. It can also pose questions to an ongoing consumer panel run by itself or another company. It may do a mall intercept study by having researchers approach people in a shopping mall and ask them questions. Or it might add a survey request at the end of calls to its customer service department.

However they conduct their surveys—online, by phone, or in person—companies must feel the information they’re getting from the mounds of data makes it all worthwhile. San Francisco-based Wells Fargo bank collects more than 50,000 customer surveys each month through its bank branches. It has used customers’ comments to begin more stringent new wait-time standards designed to improve customer satisfaction.

Of course, companies may risk creating “survey burnout” and seeing response rates plummet. Keeping a survey short and simple is one key to drawing participants. Offering incentives is another. Walmart, Rite Aid, Petco, and Staples include an invitation to fill out a survey on the cash register receipt with a chance to win a prize.27

Behavioral Research Customers leave traces of their purchasing behavior in store scanning data, catalog purchases, and customer databases. Marketers can learn much by analyzing these data. Actual purchases reflect consumers’ preferences and often are more reliable than statements they offer to market researchers. For example, grocery shopping data show that high-income people don’t necessarily buy the more expensive brands, contrary to what they might state in interviews, and many low-income people buy some expensive brands. As Chapter 3 described, there is a wealth of online data to collect from consumers. Clearly, American Airlines can learn many useful things about its passengers by analyzing ticket purchase records and online behavior.

The most scientifically valid research is experimental research, designed to capture cause-and-effect relationships by eliminating competing explanations of the findings. If the experiment is well designed and executed, research and marketing managers can have confidence in the conclusions. Experiments call for selecting matched groups of subjects, subjecting them to different treatments, controlling extraneous variables, and checking whether observed response differences are statistically significant. If we can eliminate or control extraneous factors, we can relate the observed effects to the variations in the treatments or stimuli.

American Airlines might introduce ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service on one of its regular flights from Chicago to Tokyo and charge $25 one week and $15 the next week. If the plane carried approximately the same number of first-class passengers each week and the particular weeks made no difference, the airline could relate any significant difference in the number of passengers using the service to the price charged.

RESEARCH INSTRUMENTS Marketing researchers have a choice of three main research instruments in collecting primary data: questionnaires, qualitative measures, and technological devices.

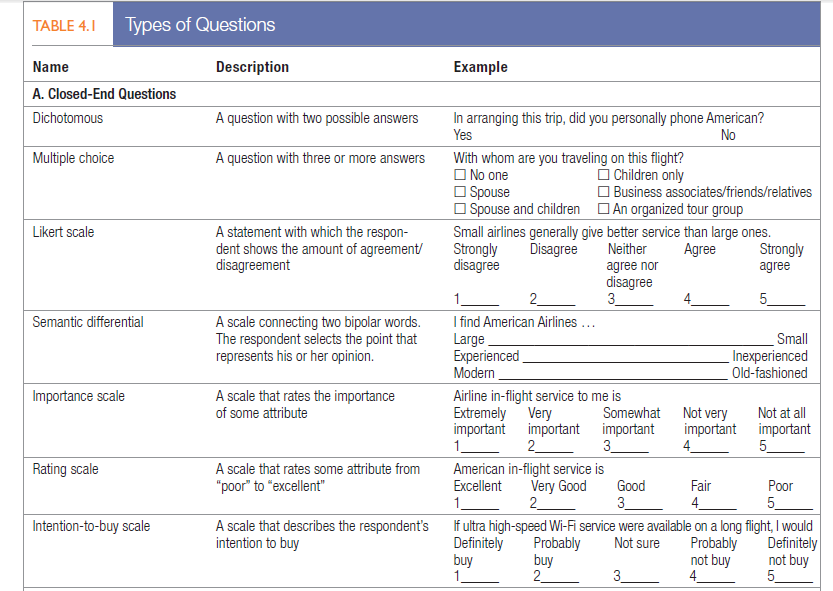

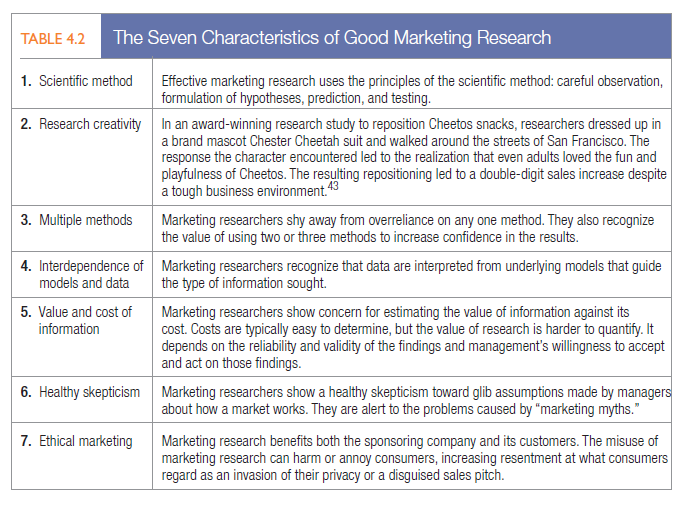

Questionnaires A questionnaire consists of a set of questions presented to respondents. Because of its flexibility, it is by far the most common instrument used to collect primary data. The form, wording, and sequence of the questions can all influence the responses, so testing and de-bugging are necessary. Closed-end questions specify all the possible answers, and the responses are easier to interpret and tabulate. Open-end questions allow respondents to answer in their own words. They are especially useful in exploratory research, where the researcher is looking for insight into how people think rather than measuring how many think a certain way. Table 4.1 provides examples of both types of questions; also see “Marketing Memo: Questionnaire Dos and Don’ts.”

Qualitative Measures Some marketers prefer qualitative methods for gauging consumer opinion because they feel consumers’ actions don’t always match their answers to survey questions. Qualitative research techniques are relatively indirect and unstructured measurement approaches, limited only by the marketing researcher’s creativity, that permit a range of responses. They can be an especially useful first step in exploring consumers’ perceptions because respondents may be less guarded and reveal more about themselves in the process.

Qualitative research does have its drawbacks. The samples are often very small, and results may not generalize to broader populations. And different researchers examining the same qualitative results may draw very different conclusions.

Nevertheless, there is increasing interest in using qualitative methods. “Marketing Insight: Getting into the Heads of Consumers” describes the pioneering ZMET approach. Other popular methods include:28

- Word associations. To identify the range of possible brand associations, ask subjects what words come to mind when they hear the brand’s name. “What does the Timex name mean to you? Tell me what comes to mind when you think of Timex watches.”

- Projective techniques. Give people an incomplete or ambiguous stimulus and ask them to complete or explain it. In “bubble exercises” empty bubbles, like those in cartoons, appear in scenes of people buying or using certain products or services. Subjects fill in the bubble, indicating what they believe is happening or being said. In comparison tasks people compare brands to people, countries, animals, activities, cars, nationalities, or even other brands.

- Visualization requires people to create a collage from magazine photos or drawings to depict their perceptions.

- Brand personification. Ask “If the brand were to come alive as a person, what would it be like, what would it do, where would it live, what would it wear, who would it talk to if it went to a party (and what would it talk about)?” For example, the John Deere brand might make someone think of a rugged Midwestern male who is hardworking and trustworthy.

- A series of increasingly specific “why” questions can reveal consumer motivation and deeper goals. Ask why someone wants to buy a Nokia cell phone. “They look well built” (attribute). “Why is it important that the phone be well built?” “It suggests Nokia is reliable” (a functional benefit). “Why is reliability important?” “Because my colleagues or family can be sure to reach me” (an emotional benefit). “Why must you be available to them at all times?” “I can help them if they’re in trouble” (a core value). The brand makes this person feel like a Good Samaritan, ready to help others.

Marketers don’t have to choose between qualitative and quantitative measures. Many use both, recognizing that their pros and cons can offset each other. For example, companies can recruit someone from an online panel to participate in an in-home product use test by capturing his or her reactions and intentions with a video diary and an online survey.

Technological Devices Galvanometers can measure the interest or emotions aroused by exposure to a specific ad or picture. The tachistoscope flashes an ad to a subject with an exposure interval that may range from less than one hundredth of a second to several seconds. After each exposure, the respondent describes everything he or she recalls. Many advances in visual technology techniques studying the eyes and face have benefited marketing researchers and managers alike.

STUDYING THE EYES AND FACE A number of increasingly cost-effective methods study the eyes and faces of consumers have been developed in recent years with diverse applications. Packaged goods companies such as P&G, Unilever, and Kimberly-Clark combine 3-D computer simulations of product and packaging designs with store layouts and use eye-tracking technology to see where consumer eyes land first, how long they linger on a given item, and so on. After doing such tests, Unilever changed the shape of its Axe body wash container, the look of the logo, and the in-store display. In the International Finance Center Mall in Seoul, Korea, two cameras and a motion detector are placed above the LCD touch screens at each of the 26 information kiosks. Facial recognition software estimates users’ age and gender, and interactive ads targeting the appropriate demographic then appear. Similar applications are being developed for digital sidewalk billboards in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco. Facial recognition cameras and software are being tested to identify and reward participating loyal U.S. customers of retailers and restaurants via opt-in smart phone updates. In one commercial application, SceneTap uses cameras with facial detection software to post information about how full a bar is, as well as the average age and gender profile of the crowd, to help bar hoppers pick their next destination.

Technology now lets marketers use skin sensors, brain wave scanners, and full-body scanners to get consumer responses.31 For example, biometric-tracking wrist sensors can measure electrodermal activity, or skin conductance, to note changes in sweat levels, body temperature and movement, and so on.32 “Marketing Insight: Understanding Brain Science” provides a glimpse into some of the new marketing research frontiers in studying the brain.33

Technology has replaced the diaries that participants in media surveys used to keep. Audiometers attached to television sets in participating homes now record when the set is on and to which channel it is tuned. Electronic devices can record the number of radio programs a person is exposed to during the day or, using Global Positioning System (GPS) technology, how many billboards a person may walk or drive by during a day.

MARKETING MEMO Conducting Informative Focus Groups

Focus groups allow marketers to hone in on issues not easily addressed by surveys. The key to using them successfully is to thoughtfully listen and carefully observe, leaving assumptions and biases behind.

Although useful insights can emerge, questions also arise about focus groups’ validity. Some researchers believe consumers are so bombarded with ads, they unconsciously (or perhaps cynically) parrot back what they’ve heard instead of what they really think. It’s always possible participants are trying to maintain their self-image and public persona, engage in “groupthink,” or satisfy a need to identify with other members. They may be unwilling to acknowledge—or even recognize—their behavior patterns and motivations, and one highly opinionated person can drown out the rest of the group. Getting the right participants is crucial, but groups can be expensive too ($3,000 to $5,000 per group).

It can be difficult to generalize the results, even from multiple focus groups. For example, within the United States, findings often vary from region to region. One firm specializing in focus group research claimed Minneapolis was the best city to get a sample of fairly well-educated people who were honest and forthcoming. Many marketers interpret focus groups in New York and other northeastern cities carefully because people there tend to be highly critical and generally don’t report that they like much.

Participants must feel relaxed and be strongly motivated to be truthful. Physical surroundings can be crucial. At one agency an executive noted, “We wondered why people always seemed grumpy and negative—people were resistant to any idea we showed them.” Finally in one session a fight broke out between participants. The problem was the room itself: cramped, stifling, forbidding. “It was a cross between a hospital room and a police interrogation room.” To fix the problem, the agency gave the room a makeover. Other firms adapt the room to fit the topic—such as designing it to look like a playroom when speaking to children. To increase interactivity among focus group members, some researchers assign pre-session homework such as diaries, photography, and videography.

Online focus groups may cost less than a quarter of an in-person focus group. They are also less intrusive, allow geographically diverse subjects to participate, and yield fast results. Proponents of traditional groups maintain that in-person sessions immerse marketers in the research process, offer a close-up look at people’s emotional and physical reactions, and ensure that sensitive materials are not leaked. In-person, marketers can also adjust the flow of discussion and delve deeply into more complex topics.

Regardless of the form it takes, the focus group is still, as one marketing executive noted, “the most cost-effective, quickest, dirtiest way to get information in rapid time on an idea.” Wharton’s Americus Reed might have said it best: “A focus group is like a chain saw. If you know what you’re doing, it’s very useful and effective. If you don’t, you could lose a limb.”

Sources: Sarah Jeffrey Kasner, “Fistfights and Feng Shui,” Boston Globe, July 21, 2001; Linda Tischler, “Every Move You Make,” Fast Company, April 2004, pp. 73-75; Dennis Rook, “Out-of-Focus Groups,” Marketing Research 15, no. 2 (Summer 2003), p. 11; Piet Levy, “In with the Old, In Spite of the New,” Marketing News, May 30, 2009, p. 19; Piet Levy, “10 Minutes with … Robert J. Morais,” Marketing News, May 30, 2011; William Boateng, “Evaluating the Efficacy of Focus Group Discussion (FGD) in Qualitative Social Research,” International Journal of Business and Social Science 3 (April 2012), pp. 54-57; Demetrius Madrigal and Bryan McClain, “Do’s and Don’ts for Focus Groups,” www.uxmatters.com, July 4, 2011.

MARKETING MEMO Marketing Questionnaire Dos And Don’ts

- Ensure that questions are without bias. Don’t lead the respondent into an answer.

- Make the questions as simple as possible. Questions that include multiple ideas or two questions in one will confuse respondents.

- Make the questions specific. Sometimes it’s advisable to add memory cues. For example, be specific with time periods.

- Avoid jargon or shorthand. Avoid trade jargon, acronyms, and initials not in everyday use.

- Steer clear of sophisticated or uncommon words. Use only words in common speech.

- Avoid ambiguous words. Words such as usually or frequently have no specific meaning.

- Avoid questions with a negative in them. It is better to say, “Do you ever…?” than “Do you never…?”

- Avoid hypothetical questions. It’s difficult to answer questions about imaginary situations. Answers aren’t necessarily reliable.

- Do not use words that could be misheard. This is especially important when administering the interview over the telephone. “What is your opinion of sects?” could yield interesting but not necessarily relevant answers.

- Desensitize questions by using response bands. To ask people their age or ask companies about employee turnover rates, offer a range of response bands instead of precise numbers.

- Ensure that fixed responses do not overlap. Categories used in fixed-response questions should be distinct and not overlap.

- Allow for the answer “other” in fixed-response questions. Precoded answers should always allow for a response other than those listed.

Source: Adapted from Paul Hague and Peter Jackson, Market Research: A Guide to Planning, Methodology, and Evaluation (London: Kogan Page, 1999). See also Hans Baumgartner and Jan-Benedict E. M. Steenkamp, “Response Styles in Marketing Research: A Cross-National Investigation,” Journal of Marketing Research (May 2001), pp. 143-56; Bert Weijters and Hans Baumgartner, “Misreponse to Reverse and Negated Items in Surveys: A Review,” Journal of Marketing Research 49 (October 2012), pp. 737-47.

MARKETING INSIGHT Getting into the Heads of Consumers

Former Harvard Business School marketing professor Gerald Zaltman, with colleagues, developed an in-depth methodology to uncover what consumers think and feel about products, services, brands, and other things. The basic assumption behind the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET) is that most thoughts and feelings are unconscious and shaped by a set of universal deep metaphors, basic orientations toward the world that shape everything consumers think, hear, say, or do. According to Zaltman, there are seven main metaphors:

- Balance: justice equilibrium and the interplay of elements;

- Transformation: changes in substance and circumstance;

- Journey: the meeting of past, present, and future;

- Container: inclusion, exclusion, and other boundaries;

- Connection: the need to relate to oneself and others;

- Resource: acquisitions and their consequences; and

- Control: sense of mastery, vulnerability, and well-being.

The ZMET technique works by first asking participants in advance to select a minimum of 12 images from their own sources (magazines, catalogs, family photo albums) to represent their thoughts and feelings about the research topic. In a one-on-one interview, the study administrator uses advanced interview techniques to explore the images with the participant and reveal hidden meanings. Finally, the participants use a computer program to create a collage with these images that

communicates their subconscious thoughts and feelings about the topic. The results often significantly influence marketing actions, as the following two examples illustrate:

- In a ZMET study about pantyhose for marketers at DuPont, some respondents’ pictures showed fence posts encased in plastic wrap or steel bands strangling trees, suggesting that pantyhose are tight and inconvenient. But another picture showed tall flowers in a vase, suggesting the product made a woman feel thin, tall, and sexy. The “love-hate” relationship in these and other pictures suggested a more complicated product relationship than the DuPont marketers had assumed.

- Although many older consumers told Danish hearing aid company Oticon that cost was the reason they were postponing purchase, a ZMET analysis revealed the bigger problem was fear of being seen as old or flawed. Oticon responded by creating Delta, a line of stylish new hearing aids that came in flashy colors such as sunset orange, racing green, or cabernet red.

ZMET has also been applied to help design the new Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh, PA, remake the classic soup labels for Campbell, and i mprove letters to prospective undergraduate applicants for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sources: Gerald Zaltman and Lindsay Zaltman, Marketing Metaphoria: What Deep Metaphors Reveal about the Minds of Consumers (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2008); Glenn L. Christensen and Jerry C. Olson, “Mapping Consumers’ Mental Models with ZMET,” Psychology & Marketing 19 (June 2002), pp. 477-502; Emily Eakin, “Penetrating the Mind by Metaphor,” New York Times, February 23, 2002; Anne Eisenberg, “The Hearing Aid as Fashion Statement,” New York Times, September 24, 2006; Mackenzie Carpenter, “The New Children’s Hospital: Design Elements Combine to Put Patients, Parents at Ease,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 26, 2009; Jennifer Williams, “Campbell’s Soup Neuromarketing Redux: There’s Chunks of Real Science in That Recipe,” Fast Company, February 22, 2010; Jay Matthews, “Admissions Office Probes Applicants’ Scary Depths,” Washington Post, July 22, 2010.

SAMPLING PLAN After choosing the research approach and instruments, the marketing researcher must design a sampling plan. This calls for three decisions:

- Sampling unit: Whom should we survey? In the American Airlines survey, should the sampling unit consist of only first-class business travelers, only first-class vacation travelers, or both? Should it include travelers under age 18? Both traveler and spouse? With the sampling unit chosen, marketers must next develop a sampling frame so everyone in the target population has an equal or known chance of being sampled.

- Sample size: How many people should we survey? Large samples give more reliable results, but it’s not necessary to sample the entire target population to achieve reliable results. Samples of less than 1 percent of a population can often provide good reliability, with a credible sampling procedure.

- Sampling procedure: How should we choose the respondents? Probability sampling allows marketers to calculate confidence limits for sampling error and makes the sample more representative. Thus, after choosing the sample, marketers could conclude that “the interval five to seven trips per year has 95 chances in 100 of containing the true number of trips taken annually by first-class passengers flying between Chicago and Tokyo.”

CONTACT METHODS Now the marketing researcher must decide how to contact the subjects: by mail, by telephone, in person, or online.

Mail Contacts The mail questionnaire is one way to reach people who would not give personal interviews or whose responses might be biased or distorted by the interviewers. Mail questionnaires require simple and clearly worded questions. Unfortunately, responses are usually few or slow.

Telephone Contacts Telephone interviewing is a good method for gathering information quickly; the interviewer is also able to clarify questions if respondents do not understand them. Interviews must be brief and not too personal. Although the response rate has typically been higher than for mailed questionnaires, telephone interviewing in the United States is getting more difficult because of consumers’ growing antipathy toward telemarketers.

In late 2003, Congress passed legislation allowing the Federal Trade Commission to restrict telemarketing calls through its “Do Not Call” registry. By mid-2010, consumers had registered more than 200 million phone numbers. Marketing research firms are exempt from the ruling, but the increasingly widespread resistance to telemarketing undoubtedly reduces the effectiveness of telephone surveys in the United States.

In other parts of the world, such restrictive legislation does not exist. Because mobile phone penetration in Africa had risen from just 1 in 50 people in 2000 to almost eighty percent of the population by 2014, marketers use cell phones there to convene focus groups in rural areas and to interact via text.34

Personal Contacts Personal interviewing is the most versatile method. The interviewer can ask more questions and record additional observations about the respondent, such as dress and body language. Personal interviewing is also the most expensive method, is subject to interviewer bias, and requires more planning and supervision. In arranged interviews, marketers contact respondents for an appointment and often offer a small payment or

incentive. In intercept interviews, researchers stop people at a shopping mall or busy street corner and request an interview on the spot. Intercept interviews must be quick, and they run the risk of including nonprobability samples.

Online Contacts The Internet offers many ways to do research. A company can embed a questionnaire on its Web site and offer an incentive for answering, or it can place a banner on a frequently visited site, inviting people to answer questions and possibly win a prize. Online product testing can provide information much faster than traditional new-product marketing research techniques.

Marketers can also host a real-time consumer panel or virtual focus group or sponsor a chat room, bulletin board, or blog where they introduce questions from time to time. They can ask customers to brainstorm or have the company’s Twitter followers rate an idea. Insights from Kraft-sponsored online communities helped the company develop its popular line of 100-calorie snacks.35

Del Monte tapped its 400-member, handpicked online community called “I Love My Dog” when it was considering a new breakfast treat for dogs. The consensus request was for something with a bacon-and-egg taste and an extra dose of vitamins and minerals. Working with the online community throughout product development, the company introduced fortified “Snausages Breakfast Bites” in half the time usually required to launch a new product.36

Online research was a $2.4 billion dollar business in 2011. A host of new online survey providers have entered the market, such as SurveyMonkey, Survey-Gizmo, Qualtrics, and Google Consumer Surveys. Founded in 1999, SurveyMonkey has over 15 million registered users. Members can create surveys to quickly post on blogs, Websites, Facebook, or Twitter. 37 Like any survey, however, online surveys need to ask the right people the right questions on the right topic.

Other means to use the Internet as a research tool including tracking how customers clickstream through the company’s Web site and move to other sites. Marketers can post different prices, headlines, and product features on separate Web sites or at different times to compare their relative effectiveness. Researchers like Bluefin Labs monitor all relevant Twitter tweets, Facebook posts, and broadcast television stories to provide companies with real-time trend analysis.38

Yet, as popular as online research methods are, smart companies use them to augment rather than replace more traditional methods. Like any method, online research has pros and cons. Here are some advantages:

- Online research is inexpensive. A typical online survey can cost 20 percent to 50 percent less than a conventional survey, and return rates can be as high as 50 percent.

- Online research is expansive. There are essentially no geographical boundaries, allowing marketers to consider a wide range of possible respondents.

- Online research is fast. The survey can automatically direct respondents to applicable questions, store data, and transmit results immediately.

- Responses tend to be honest and thoughtful. People may be more relaxed and candid when they can answer on their own time and respond privately without feeling judged, especially on sensitive topics (such as “how often do you bathe or shower?”).39

- Online research is versatile. Virtual reality software lets visitors inspect 3-D models of products such as cameras, cars, and medical equipment and manipulate product characteristics. Online community blogs allow customer participants to interact with each other.

Some disadvantages include:

- Samples can be small and skewed. Some 28 percent of U.S. households still lacked broadband Internet access in 2014; the percentage is higher among lower-income groups, in rural areas, and in most parts of Asia, Latin America, and Central and Eastern Europe, where socioeconomic and education levels also differ.40 Although Internet access will increase, online market researchers must find creative ways to reach population segments on the other side of the “digital divide.” Combining offline sources with online findings and providing temporary Internet access at locations such as malls and recreation centers are options. Some research firms use statistical models to fill in the gaps left by offline consumer segments.

- Online panels and communities can suffer excessive turnover. Members may become bored and flee or, worse, stay but participate halfheartedly. Panel and community organizers can raise recruiting standards, downplay incentives, and monitor participation and engagement levels. A constant flow of new features, events, and activities can keep members interested and engaged.

- Online market research can suffer technological problems and inconsistencies. Because browser software varies, the designer’s final product may look very different on the research subject’s screen.

Online researchers have also begun to use text messaging in various ways—to conduct a chat with a respondent, to probe more deeply with a member of an online focus group, or to direct respondents to a Web site. Text messaging is also a useful way to get teenagers to open up on topics.

MARKETING INSIGHT Understanding Brain Science 133

As an alternative to traditional consumer research, some researchers have begun to develop sophisticated techniques from neuroscience that monitor brain activity to better gauge consumer responses to marketing. The term neuromarketing describes brain research on the effect of marketing stimuli. Firms are using EEG (electroencephalograph) technology to correlate brand activity with physiological cues such as skin temperature or eye movement and thus gauge how people react to ads.

Researchers studying the brain have found different results from conventional research methods. One group of researchers at UCLA used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to find that the Super Bowl ads for which subjects displayed the highest brain activity were different from the ads with the highest stated preferences. Other research found little effect from product placement unless the products in question played an integral role in the storyline.

Several studies have found higher correlations with brain wave research and behavior than with surveys. One study found that brain waves better predicted music purchases than stated music preferences. One major finding from neurological consumer research is that many purchase decisions appear to be characterized “as a largely unconscious habitual process, as distinct from the rational, conscious, information-processing model of economists and traditional marketing textbooks.” Even basic decisions, such as the purchase of gasoline, seem to be influenced by brain activity at the subrational level.

A group of researchers in England used EEG to monitor cognitive functions related to memory recall and attentiveness for 12 different regions of the brain as subjects were exposed to advertising. Brain wave activity in different regions indicated different emotional responses. For

example, heightened activity in the left prefrontal cortex is characteristic of an “approach” response to an ad and indicates an attraction to the stimulus. In contrast, a spike in brain activity in the right prefrontal cortex is indicative of a strong revulsion to the stimulus. In yet another part of the brain, the degree of memory formation activity correlates with purchase intent. Other research has shown that people activate different regions of the brain in assessing the personality traits of other people than they do when assessing brands.

Although it may offer different insights from conventional techniques, neurological research can still be fairly expensive and has not been universally accepted. Given the complexity of the human brain, many researchers caution that it should not form the sole basis for marketing decisions. The measurement devices to capture brain activity can also be highly obtrusive, using skull caps studded with electrodes or creating artificial exposure conditions.

Others question whether neurological research really offers unambiguous implications for marketing strategy. Brian Knutson, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at Stanford University, compares the use of EEG to “standing outside a baseball stadium and listening to the crowd to figure out what happened.” Other critics worry that if the methods do become successful, they will only lead to more marketing manipulation by companies. Despite controversy, marketers’ endless pursuit of deeper insights about consumers’ response to marketing virtually guarantees continued interest in neuromarketing.

Sources: Carolyn Yoon, Angela H. Gutchess, Fred Feinberg, and Thad A. Polk, “A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Neural Dissociations between Brand and Person Judgments,” Journal of Consumer Research 33 (June 2006), pp. 31-40; Martin Lindstrom, Buyology: Truth and Lies about Why We Buy (New York: Doubleday, 2008); Brian Sternberg, “How Couch Potatoes Watch TV Could Hold Clues for Advertisers,” Boston Globe, September 6, 2009, pp. G1, G3; Kevin Randall, “Neuromarketing Hope and Hype: 5 Brands Conducting Brain Research,” Fast Company, September 15, 2009; Todd Essig, “The Future of Focus Groups: My Brain Knows What You Like,” Forbes, April 28, 2012; Carmen Nobel, “Neuromarketing: Tapping into the ‘Pleasure Center’ of Consumers,” Forbes, February 1, 2013.

3. STEP 3: COLLECT THE INFORMATION

The data collection phase of marketing research is generally the most expensive and error-prone. Some respondents will be away from home, offline, or otherwise inaccessible; they must be contacted again or replaced. Others will refuse to cooperate or will give biased or dishonest answers.

Internationally, one of the biggest obstacles to collecting information is the need to achieve consistency.41 Latin American respondents may be uncomfortable with the impersonal nature of the Internet and need interactive elements in a survey so they feel they’re talking to a real person. Respondents in Asia, on the other hand, may feel more pressure to conform and may not be as forthcoming in focus groups as online. Sometimes the solution may be as simple as ensuring the right language is used.

4. STEP 4: ANALYZE THE INFORMATION

The next-to-last step in the process is to extract findings by tabulating the data and developing summary measures. The researchers now compute averages and measures of dispersion for the major variables and apply some advanced statistical techniques and decision models in the hope of discovering additional findings. They may test different hypotheses and theories, applying sensitivity analysis to test assumptions and the strength of the conclusions.

5. STEP 5: PRESENT THE FINDINGS

As the last step, the researcher presents the findings. Researchers are increasingly asked to play a proactive, consulting role in translating data and information into insights and recommendations for management. “Marketing Insight: Bringing Marketing Research to Life with Personas” describes an approach that some researchers are using to maximize the impact of their consumer research findings.

The main survey findings for the American Airlines case showed that:

- Passengers would use ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service primarily to stay connected and receive and send large documents and e-mails. Some would also surf the Web to download videos and songs. They would charge the cost back to their employers.

- At $25, about 5 of 10 first-class passengers would use Wi-Fi service during a flight; at $15, about 6 would. Thus, a fee of $15 would produce less revenue ($90 = 6 x $15) than $25 ($125 = 5 x $25). Assuming the same flight takes place 365 days a year, American could collect $45,625 (= $125 x 365) annually. Given an investment of $90,000 per plane, it would take two years for each to break even.

- Offering ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service would strengthen American Airlines’ image as an innovative and progressive carrier and earn it some new passengers and customer goodwill.

MARKETING INSIGHT Bringing Marketing Research to Life with Personas

To bring all their acquired information and insights to life, some researchers are employing personas. Personas are detailed profiles of one, or perhaps a few, hypothetical target consumers, imagined in terms of demographic, psychographic, geographic, or other descriptive at- titudinal or behavioral information. Photos, images, names, or short bios help convey how the target customer looks, acts, and feels so marketers can incorporate a well-defined target-customer point of view in all their marketing decision making. Many software companies, Microsoft in particular, have used personas to help improve user interfaces and experiences, and marketers have broadened the application. For example:

- Unilever’s biggest and most successful hair-care launch, for Sunsilk, was aided by insights into the target consumer the company dubbed “Katie.” The Katie persona outlined the 20-something female’s hair-care needs, but also her perceptions and attitudes and the way she dealt with her everyday “dramas.”

- Specialty tool and equipment maker Campbell Hausfeld relied on the many retailers it supplied, including Home Depot and Lowe’s, to help it keep in touch with consumers. After developing eight consumer profiles, including a female do-it-yourselfer and an elderly consumer, the firm was able to successfully launch new products such as drills that weighed less or that included a level for picture hanging.

Although personas provide vivid information to aid marketing decision making, it’s important not to overgeneralize. Any target market may have a range of consumers who vary along a number of key dimensions, so researchers sometimes employ two to six personas. Using quantitative, qualitative, and observational research, Best Buy developed five customer personas to guide the redesign and relaunch of GeekSquad.com, its national computer-support service:

- “Jill”—a suburban mom who uses her computer daily and depends on the Geek Squad as on a landscaper or plumber.

- “Charlie”—a 50-plus male who is curious about technology but needs an unintimidating guide.

- “Daryl”—a technologically savvy hands-on experimenter who occasionally needs a helping hand.

- “Luis”—a time-pressed small business owner whose primary goal is to complete tasks as expediently as possible.

- “Nick”—a prospective Geek Squad agent who views the site critically and needs to be challenged.

To satisfy Charlie, a prominent 911 button was added to the upper right-hand corner in case a crisis arose, but to satisfy Nick, Best Buy created a whole channel devoted to geek information.

Sources: Dale Buss, “Reflections of Reality,” Point, June 2006, pp. 10-11; Todd Wasserman, “Unilever, Whirlpool Get Personal with Personas,” Brandweek, September 18, 2006, p. 13; Daniel B. Honigman, “Persona-fication,” Marketing News, April 1,2008, p. 8; Lisa Sanders, “Major Marketers Get Wise to the Power of Assigning Personas,” Advertising Age, April 9, 2007, p. 36; Paul Murray, “Who Are They?,” www.chiefmarketer.com, June/July 2010, pp. 53-54; Lauren Sorenson, “6 Core Benefits of Well-Defined Marketing Personas,” www.blog.hotspot.com, December 13, 2011.

6. STEP 6: MAKE THE DECISION

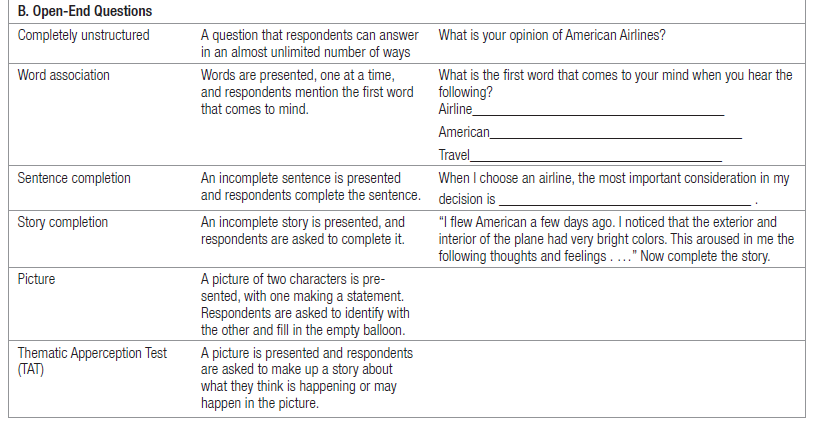

The American Airlines managers who commissioned the research need to weigh the evidence. If their confidence in the findings is low, they may decide against introducing ultra high-speed Wi-Fi service. If they are predisposed to launching it, the findings support their inclination. They may even decide to study the issue further and do more research. The decision is theirs, but rigorously done research provides them with insight into the problem (see Table 4.2).42

Some organizations use marketing decision support systems to help their marketing managers make better decisions. MIT’s John Little defined a marketing decision support system (MDSS) as a coordinated collection of data, systems, tools, and techniques, with supporting software and hardware, by which an organization gathers and interprets relevant information from business and environment and turns it into a basis for marketing ac- tion.44 Once a year, Marketing News lists hundreds of current marketing and sales software programs that assist in designing marketing research studies, segmenting markets, setting prices and advertising budgets, analyzing media, and planning sales force activity.

Source: Kotler Philip T., Keller Kevin Lane (2015), Marketing Management, Pearson; 15th Edition.

I am continually searching online for tips that can assist me. Thx!