Exploration and testing are two processes through which we construct knowledge. To explore in management consists of discovering, or looking further into, a structure or a way of functioning in order to satisfy two broad objectives: the quest for explanation (and prediction) and the quest for comprehension. Through exploration, researchers satisfy their initial intentions: to propose innovative theoretical results – to create new theoretical links between concepts, or to integrate new concepts into a given theoretical field. Testing is the set of operations by which we assess the reality of one or more theoretical elements. Testing is also used to evaluate the significance of hypotheses, models or theories to a given explanation.

The dichotomy (exploration and test) we suggest in this chapter is justified by the different types of logic that are characteristic of these two processes. To explore, the researcher adopts an approach that is either inductive or abductive, or both – whereas testing calls for a deductive method.

1. Logical Principles

1.1. Deduction

By definition, deduction is characterized by the fact that, if the hypotheses formulated initially (premises) are true, then the conclusion that follows logically from these premises must necessarily be true.

Example: A classic deduction: the syllogism of Socrates

-

- All men are mortal.

- Socrates is a man.

- Socrates is mortal.

In this example of deductive logic, (1) and (2) are the premises and (3) the conclusion. It is not possible that (3) is false once (1) and (2) are accepted as true. Schematically this argument follows the following logic: every A is B, C is A, therefore C is B. (See also Chapter 1)

We should not, however, limit deduction to the type of syllogism evoked in the above example. In fact, logicians make a distinction between formal and constructive deduction. Formal deduction is an argument or an inference – a logical operation by which one concludes the necessary consequence of one or several propositions – that consists of moving from the implicit to the explicit, the most usual form being the syllogism. Although formal deduction involves valid logical reasoning, it is sterile insofar as the conclusion does not enable us to learn a new fact. The conclusion is already presupposed in the premises; consequently the argument is tautological. Constructive deduction, on the other hand, while also leading to a necessary conclusion, makes a contribution to our knowledge. The conclusion is a demonstration – composed not only of the contents of the premises, but also of the logic by which one shows that one circumstance is the consequence of another.

Deductive logic thus underpins the hypothetico-deductive method. This consists of elaborating one or more general hypotheses, and then comparing them against a particular reality in order to assess the validity of the hypotheses formulated initially.

1.2. Induction and abduction

Induction, in logic, usually means to assert the truth of a general proposition by considering particular cases that support it. Mill (1843: 26) defines it as ‘the operation of discovering and proving general propositions . . . by which we infer that what we know to be true in a particular case or cases, will be true in all cases which resemble the former in certain assignable respects’. Induction is called summative (or complete) if it proceeds through an enumeration of all cases that its conclusion is valid for. Induction is called ampliative (or incomplete) if its conclusion goes beyond its premises. That is, the conclusion is not a logical consequence of the premises. Ampliative induction is thus an inconclusive argument.

This argument illustrates the principle of induction. Researchers in management, however, frequently explore complex contexts; drawing from them a large number of observations of a variety of natures which are at first ambiguous. They will then attempt to structure their observations so as to derive meaning from them. In the social sciences, the aim is not really to produce universal laws, but rather to propose new theoretical conceptualizations that are valid and robust, and are thought through in minute detail. It is said, then, that the researcher proceeds by abduction (a term employed in particular by Eco, 1990) or by adduction (term used by Blaug, 1992).

Thus induction is a logical inference which confers on a discovery an a priori constancy (that is, gives it the status of law), whereas abduction confers on it an explanatory status which then needs to be tested further if it is to be tightened into a rule or a law.

By applying an abductive method, the researcher in management can use analogy and metaphor to account for observed phenomena, or to illustrate or explain propositions. The aim is to use the comparison as an aid in deriving meaning. An analogy is an expression of a relationship or a similarity between several different elements. Consequently, to argue analogically involves drawing connections and noting resemblances (so long as these indicate some sort of relationship). The researcher proceeds then by association, through familial links between observed phenomena. Metaphors are transfers by analogical substitution – a metaphor is a figure of speech by which we give a new signification to a name or a word, in order to suggest some similarity. The metaphor is thus relevant only as far as the comparison at hand; it can be described as an abridged comparison.

In management, recourse to analogical reasoning or metaphor is common when researchers choose to construct knowledge through exploration. Pentland (1995) establishes a relationship between the structures and processes of grammatical models and the structure characteristics of an organizational environment along with the corresponding processes likely to be produced within it. Using metaphor as a transfer by analogical substitution, Pentland demonstrates to what extent the ‘grammatical metaphor’ can be useful in understanding organizational processes.

In his work Images of Organization, Morgan (1986) discusses using metaphor as an aid in analyzing organizations. Morgan sees metaphor as a tool with which to decode and to understand. He argues that metaphorical analysis is an effective way of dealing with organizational complexity. Morgan raises the metaphorical process to the status of legitimate research device. He distinguishes several metaphorical conceptions of the organization: in particular as a machine, an organism, a brain and a culture. The choice of which metaphorical vision to borrow influences the meaning produced.

1.3. Constructing knowledge

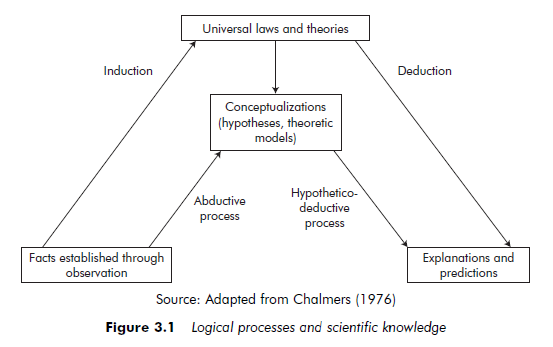

Although so far we have differentiated between induction and deduction, used respectively for exploration and testing, these two logics are complementary when it comes to the construction of scientific knowledge (see Figure 3.1).

It is traditionally considered that deductive reasoning moves from the general to the particular, and inductive from the particular to the general. For Blaug (1992) however, induction and deduction are distinguished by the character – demonstrative or not – of the inferences formed. The conclusions of inductive or abductive reasoning are not demonstrations. They represent relationships that, through the thoroughness with which they have been established, have achieved the status of valid propositions. These propositions are not, however, certain – as those elaborated through deduction can be. They are regarded as inconclusive, or uncertain, inferences.

Yet ‘certain’ and ‘uncertain’ inferences are both integral to the process of constructing new knowledge. From our observations, we can be led to infer the existence of laws (through induction – an uncertain inference) or, more reasonably, conceptualizations: explanations or conjectures (through abduction – again uncertain). These laws or conceptualizations might then be used as premises, and be subjected to tests. By testing them we might hopefully develop inferences of which we are certain (through deduction). In this way, researchers are able to advance explanatory and/or predictive conclusions.

2. Theoretical Elements

Exploration can often lead researchers to formulate one or more temporary working hypotheses. These hypotheses may in turn be used as the basis of further reflection, or in structuring a cohesive body of observations. But while the final result of the exploration process (using an abductive approach) takes the form of hypotheses, models, or theories, these constitute the starting point of the testing process (in which deduction is employed). It is from these theoretical elements that the researcher will try to find an answer to the question he or she posed initially.

2.1. Hypotheses

In everyday usage, a hypothesis is a conjecture about why, when, or how an event occurs. It is a supposition about the behavior of different phenomena or about the relationships that may exist between them. One proposes, as a hypothesis, that a particular phenomenon is an antecedent or a consequent of, or is invariably concomitant to, other given phenomena. Developed through theoretical reflection, drawing on the prior knowledge the researcher has of the phenomena being studied, hypotheses are actually the relationships we establish between our theoretical concepts.

A concept refers to certain characteristics or phenomena that can be grouped together. Alternatively, a concept represents similarities in otherwise diverse phenomena … Concepts are located in the world of thought . . . are abstracted forms and do not reflect objects in their entirety but comprehend only a few aspects of objects.

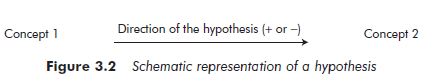

When we map out a hypothesis, we explain the logic of the relations that link the concepts involved (see Figure 3.2). From the moment it has been formulated, the hypothesis replaces the initial research question, and takes the form of a provisional answer.

If the direction of the hypothesis is positive, the more Concept 1 is present, the stronger Concept 2 will be; if the direction is negative, then the presence of Concept 1 will lessen the presence of Concept 2.

Like the research subject, a research hypothesis should have certain specific properties. First, the hypothesis should be expressed in observable form. To assess its value as an answer to the research question, it needs to be weighed against experimental and observational data. It should therefore indicate the type of observations that must be collected, as well as the relationships that must be established between these observations in order to verify to what extent the hypothesis is confirmed (or not) by facts.

For example, let us consider the following hypothesis: ‘There are as many readings of a text as there are readers of it.’ Here we have an expression that cannot be operationalized, and which therefore cannot constitute an acceptable research hypothesis in the sense we have outlined. In reading a text we acquire a mental image which will always lose something when it is verbalized. The concept of protocol sentences is generally applied in such a case, but this can still only partly account for the results of the reading.

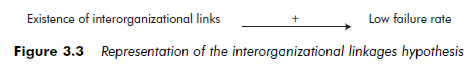

On the other hand, a hypothesis such as ‘Organizations with interorganizational linkages should show a lower failure rate than comparable organizations without such linkages’ (Miner et al., 1990: 691) indicates the kind of observations we need to have access to if we are to assess its legitimacy. The researcher is led to identify the existence or not of interorganizational links and the suspension or not of the organization’s activities. The hypothesis can be represented by the diagram in Figure 3.3.

Second, hypotheses should not be relationships based on social prejudices or stereotypes. For example, the hypothesis that ‘absenteeism increases with an increase in the number of women in a company’ leads to a distorted view of social reality. Ideological expressions cannot be treated as hypotheses.

In practice, it is rare for researchers to restrict themselves to only one hypothesis. The researcher is most often led to work out a body of hypotheses, which must be coherent and logically consistent. It is only then that we have the form of a model.

2.2. Models

There are many definitions of the term ‘model’. According to Kaplan (1964: 263): ‘We say that any system A is a model of system B if the study of A is useful for the understanding of B without regard to any direct or indirect causal connection between A and B.’

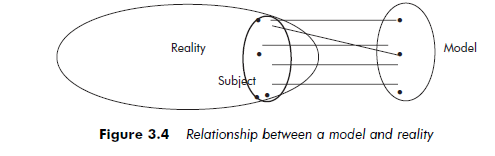

In the social sciences, a model is a schematic illustration of physical or cognitive relationships among its elements. In practice, a ‘model’ is a simplified representation of a process or a system that is designed to explain and/or simulate a real situation. The model is then schematic, in that the number of parameters it incorporates is sufficiently limited that they can be readily explained and manipulated.

The subject-model relationship is by nature subjective. In other words, the model does not aim to account for every aspect of the subject, nor even every aspect of any one possible approach to the subject (see Figure 3.4).

2.3. Theories

In broad terms, a theory can be said to be a body of knowledge, which forms a system, on a particular subject or in a particular field. But this definition is of limited use in practice. That said, as authors continue to formalize more precisely what they mean by theory, the number of definitions of the term continues to increase. Zaltman, et al. (1973) note ten different definitions, all of which have one point in common: theories are sets of interconnected propositions. Ambiguity or confusion between the terms ‘theory’ and ‘model’ is not uncommon.

It is not the aim of the present chapter to settle this debate. We will use the term here with the definition suggested by Bunge (1967: 387):

Theory designates a system of hypotheses. A set of scientific hypotheses is a scientific theory if and only if it refers to a given factual subject matter and every member of the set is either an initial assumption (axiom, subsidiary assumption, or datum) or a logical consequence of one or more initial assumptions.

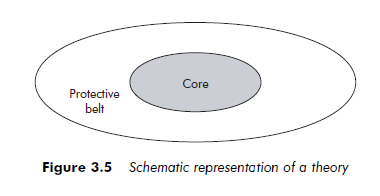

To be more precise, we can adopt the vocabulary of Lakatos (1974), and say that a theory is a system made up of a ‘core’ and a ‘protective belt’ (see Figure 3.5). The core includes the basic hypotheses that underlie the theory, those which are required – they can be neither rejected nor modified. In other words, the core cannot be modified by methodological decision. It is surrounded by the protective belt, which contains explicit auxiliary hypotheses that supplement those of the core, along with observations and descriptions of initial conditions (Chalmers, 1976).

Researchers in management do not deal with laws or universal theories. Instead they construct or test theories that are generally qualified as substantive. It is important to distinguish the claims of such substantive theories from those of more universal theories. Glaser and Strauss (1967) make a distinction between substantive and formal theories: a substantive theory is a theoretical development in direct relation to an empirical domain, whereas a formal theory relates to a conceptual domain.

A concept of inclusion exists between these two levels of theories. A formal theory usually incorporates several substantive theories that have been developed in different or comparable empirical fields. While formal theories are more ‘universal’ than substantive theories, which are ‘rooted’ in a context, a formal theory generally evolves from the successive integration of several substantive theories (Glaser and Strauss, 1967).

In the above discussion we have looked at the two types of logic that underlie the two processes we employ in constructing knowledge (exploration and testing). We have also considered the theoretical elements key to these logical processes.

Source: Thietart Raymond-Alain et al. (2001), Doing Management Research: A Comprehensive Guide, SAGE Publications Ltd; 1 edition.

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021

26 Jul 2021