Total quality is not just one individual concept. It is a number of related concepts pulled together to create a comprehensive approach to doing business. Many people contributed in meaningful ways to the development of the various concepts that are known collectively as total quality. The three major contributors are W. Edwards Deming, Joseph M. Juran, and Philip B. Crosby. To these three, many would add Armand V. Feigenbaum and a number of Japanese experts, such as Shigeo Shingo.

1. Deming’s Contributions

Of the various quality pioneers in the United States, the best known is W. Edwards Deming. Deming’s contribution was his ability to see the big picture, envision the impact of quality on it, and meld different management philosophies into a new, workable, unitary whole. More than any other quality pioneer, Deming is responsible for the total quality approach.

Deming came a long way to achieve the status of internationally acclaimed quality expert. During his formative years, Deming’s family bounced from small town to small town in Iowa and Wyoming, trying in vain to rise out of poverty. These early circumstances gave Deming a lifelong appreciation for economy and thrift. In later years, even after he was generating a substantial income, Deming maintained only a simple office in the basement of his modest home out of which he conducted his international consulting business.

Working as a janitor and at other odd jobs, Deming worked his way through the University of Wyoming, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering. He went on to receive a master’s degree in mathematics and physics from the University of Colorado and a doctorate in physics from Yale.

His only full-time employment for a corporation was with Western Electric. Many feel that what he witnessed during his employment there had a major impact on the direction the rest of his life would take. Deming was disturbed by the amount of waste he saw at Western Electrics Hawthorne plant. It was there that he pioneered the use of statistics in quality.

Although Deming was asked in 1940 to help the U.S. Bureau of the Census adopt statistical sampling techniques, his reception in the United States during these early years was not positive. With little real competition in the international marketplace, major U.S. corporations felt little need for his help. Corporations from other countries were equally uninterested. However, attitudes toward Deming’s idea were changed by World War II. The need to rebuild after the devastation of World War II, particularly in bombed-out Japan, brought Deming’s ideas on quality to the forefront.

During World War II, almost all of Japan’s industry went into the business of producing war materials. After the war, those firms had to convert to the production of consumer goods, and the conversion was not very successful. To have a market for their products, Japanese firms had to enter the i nternational marketplace. This move put them in direct competition with companies from the other industrialized countries of the world, and the Japanese firms did not fare well.

By the late 1940s, key industrial leaders in Japan had finally come to the realization that the key to competing in the international marketplace is quality. At this time, Shigeiti Mariguti of Tokyo University, Sizaturo Mishibori of Toshiba, and several other Japanese leaders invited Deming to visit Japan and share his views on quality. Unlike their counterparts in the United States, the Japanese industrialists accepted Deming’s views, learned his techniques, and adopted his philosophy. So powerful was Deming’s impact on industry in Japan that the most coveted award a company there can win is the Deming Prize. In fact, the standards that must be met to win this prize are so difficult and so strenuously applied that it is now being questioned by some Japanese companies.

By the 1980s, leading industrialists in the United States were where their Japanese counterparts had been in the late 1940s. At last, Deming’s services began to be requested in his own country. By this time, Deming was over 80 years old. He had not been received as openly and warmly in the United States as he was in Japan. Deming’s attitude toward corporate executives in the United States can be described as cantankerous at best.

Deming’s contributions to the quality movement would be difficult to overstate. Many consider him the founder of the movement. The things for which he is most widely known are the Deming Cycle, his Fourteen Points, and his Seven Deadly Diseases.8

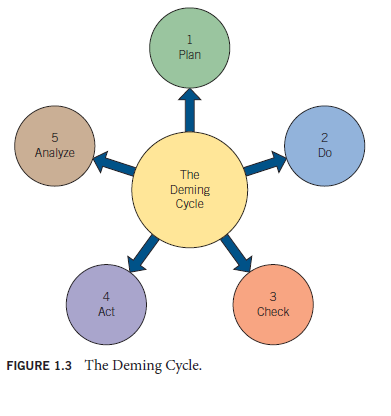

The Deming Cycle Summarized in Figure 1.3, the Deming Cycle was developed to link the production of a product with consumer needs and focus the resources of all departments (research, design, production, marketing) in a cooperative effort to meet those needs. The Deming Cycle proceeds as follows:

- Conduct consumer research and use it in planning the product (plan).

- Produce the product (do).

- Check the product to make sure it was produced in accordance with the plan (check).

- Market the product (act).

- Analyze how the product is received in the marketplace in terms of quality, cost, and other criteria (analyze).

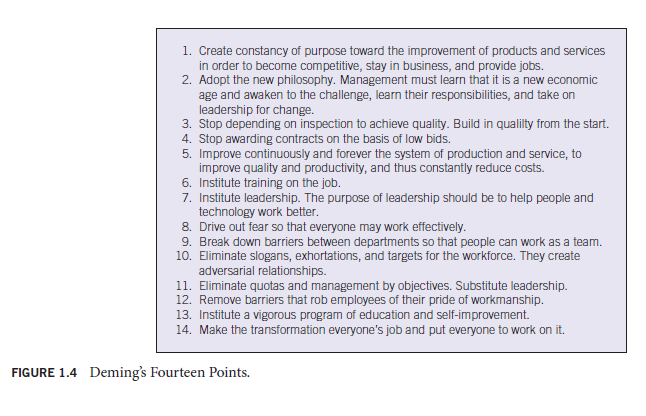

Deming’s Fourteen Points Deming’s philosophy is both summarized and operationalized by his Fourteen Points, which are contained in Figure 1.4. Deming modified the specific wording of various points over the years, which accounts for the minor differences among the Fourteen Points as described in various publications. Deming stated repeatedly in his later years that if he had it all to do over again, he would leave off the numbers.

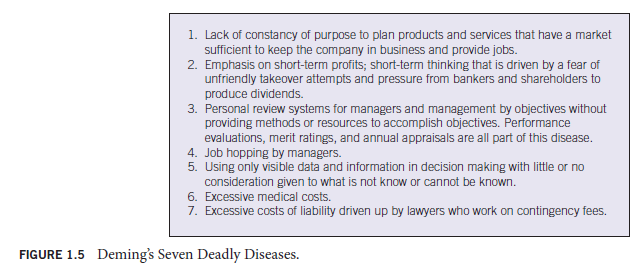

Deming’s Seven Deadly Diseases The Fourteen Points summarize Deming’s views on what a company must do to effect a positive transition from business as usual to world-class quality. The Seven Deadly Diseases summarize the factors that he believed can inhibit such a transformation (see Figure 1.5).

The description of these factors rings particularly true when viewed from the perspective of U.S. firms trying to compete in the global marketplace. Some of these factors can be eliminated by adopting the total quality approach, but three cannot. This does not bode well for U.S. firms trying to regain market share. Total quality can eliminate or reduce the impact of a lack of consistency, personal review systems, job hopping, and using only visible data. However, total quality will not free corporate executives from pressure to produce short-term profits, excessive medical costs, or excessive liability costs. These are diseases of the nation’s financial, health care, and legal systems, respectively.

By finding ways for business and government to cooperate appropriately without collaborating inappropriately, other industrialized countries have been able to focus their industry on long-term rather than short-term profits, hold down health care costs, and prevent the proliferation of costly litigation that has occurred in the United States. Excessive health care and legal costs represent non-value-added costs that must be added to the cost of products produced and services delivered in the United States.

2. Juran’s Contributions

Joseph M. Juran ranks near Deming in the contributions he has made to quality and the recognition he has received as a result. His Juran Institute Inc. in Wilton, Connecticut, is an international leader in conducting training, research, and consulting activities in the area of quality management (see Figure 1.6). Quality materials produced by Juran have been translated into 14 different languages.

Juran holds degrees in both engineering and law. The emperor of Japan awarded him the Order of the Sacred Treasure medal, in recognition of his efforts to develop quality in Japan and to promote friendship between Japan and

figure 1.6 Services Provided by the Juran Institute.

the United States. Juran is best known for the following contributions to the quality philosophy:

- Juran’s Three Basic Steps to Progress

- Juran’s Ten Steps to Quality Improvement

- The Pareto Principle

- The Juran Trilogy

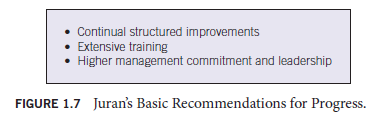

Juran’s Three Basic Steps to Progress Juran’s Three Basic Steps to Progress (listed in Figure 1.7) are broad steps that, in Juran’s opinion, companies must take if they are to achieve world-class quality. He also believes there is a point of diminishing return that applies to quality and competitiveness.

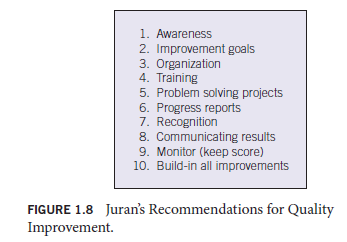

Juran’s Ten Steps to Quality Improvement Examining Juran’s Ten Steps to Quality Improvement (in Figure 1.8), you will see some overlap between them and Deming’s Fourteen Points. They also mesh well with the philosophy of quality experts whose contributions are explained later in this chapter.

The Pareto Principle The Pareto Principle espoused by Juran shows up in the views of most quality experts, although it often goes by other names. According to this principle, organizations should concentrate their energy on eliminating the vital few sources that cause the majority of problems. Further, both Juran and Deming believe that systems that are controlled by management are the systems in which the majority of problems occur.

The Juran Trilogy The Juran Trilogy summarizes the three primary managerial functions. Juran’s views on these functions are explained in the following sections.

Quality Planning Quality planning involves developing the products, systems, and processes needed to meet or exceed customer expectations. The following steps are required:

- Determine who the customers are.

- Identify customers’ needs.

- Develop products with features that respond to customer needs.

- Develop systems and processes that allow the organization to produce these features.

- Deploy the plans to operational levels.

Quality Control The control of quality involves the following processes (see Figure 1.9):

- Assess actual quality performance.

- Compare performance with goals.

- Act on differences between performance and goals.

Quality Improvement The improvement of quality should be ongoing and continual:

- Develop the infrastructure necessary to make annual quality improvements.

- Identify specific areas in need of improvement, and implement improvement projects.

- Establish a project team with responsibility for completing each improvement project.

- Provide teams with what they need to be able to diagnose problems to determine root causes, develop solutions, and establish controls that will maintain gains made.

3. Crosby’s Contributions

Philip B. Crosby started his career in quality later than Deming and Juran. His corporate background includes 14 years as director of quality at ITT Corporation (1965-1979). He left ITT in 1979 to form Philip Crosby Associates, an international consulting firm on quality improvement, which he ran until 1992, when he retired as CEO to devote his time to lecturing on quality-related issues. More recently, Crosby had once again entered the business arena as a quality consultant until his death in 2001.

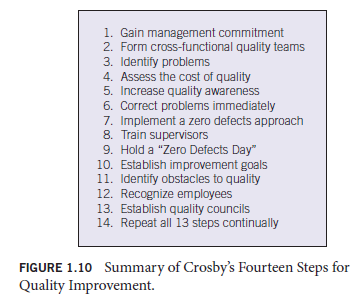

Crosby, who defined quality simply as conformance, is best known for his advocacy of zero-defects management and prevention as opposed to statistically acceptable levels of quality. He is also known for his Quality Vaccine and Crosby’s Fourteen Steps to Quality Improvement.

Crosby’s Quality Vaccine consists of three ingredients:9

- Determination

- Education

- Implementation

His Fourteen Steps to Quality Improvement are listed in Figure 1.10.

Source: Goetsch David L., Davis Stanley B. (2016), Quality Management for organizational excellence introduction to total Quality, Pearson; 8th edition.

magnificent issues altogether, you just won a new reader. What could you recommend in regards to your publish that you just made a few days in the past? Any sure?

I view something truly interesting about your web site so I saved to fav.