If you own a bond, you are entitled to a fixed set of cash payoffs. Every year until the bond matures, you collect regular interest payments. At maturity, when you get the final interest payment, you also get back the face value of the bond, which is called the bond’s principal.

1. A Short Trip to Paris to Value a Government Bond

Why are we going to Paris, apart from the cafes, restaurants, and sophisticated nightlife? Because we want to start with the simplest type of bond, one that makes payments just once a year.

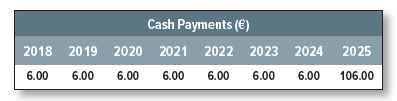

French government bonds, known as OATs (short for Obligations Assimilables du Tresor), pay interest and principal in euros (€). Suppose that in October 2017 you decide to buy €100 face value of the 6.00% OAT maturing in October 2025. Each year until the bond matures, you are entitled to an interest payment of .06 X 100 = €6.00. This amount is the bond’s coupon.1 When the bond matures in 2025, the government pays you the final €6.00 interest, plus the principal payment of €100. Your first coupon payment is in one year’s time, in October 2018. So the cash payments from the bond are as follows:

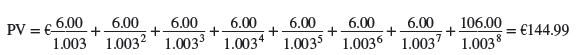

What is the present value of these payments? It depends on the opportunity cost of capital, which in this case equals the rate of return offered by other government debt issues denominated in euros. In October 2017, other medium-term French government bonds offered a return of just .3%. That is what you were giving up when you bought the 6.00% OATs. Therefore, to value the 6.00% OATs, you must discount the cash flows at .3%:

Bond prices are usually expressed as a percentage of face value. Thus the price of your 6.00% OAT was quoted as 144.99%.

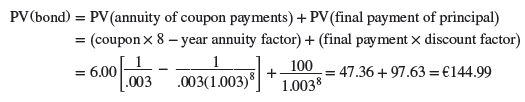

You may have noticed a shortcut way to value this bond. Your OAT amounts to a package of two investments. The first investment gets the eight annual coupon payments of €6.00 each. The second gets the €100 face value at maturity. You can use the annuity formula from Chapter 2 to value the coupon payments and then add on the present value of the final payment.

Thus, the bond can be valued as a package of an annuity (the coupon payments) and a single, final payment (the repayment of principal).2

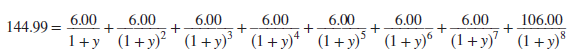

We just used the .3% interest rate to calculate the present value of the OAT. Now we turn the valuation around: If the price of the OAT is 144.99%, what is the interest rate? What return do investors get if they buy the bond and hold it to maturity? To answer this question, you need to find the value of the variable y that solves the following equation:

The rate of return y is called the bond’s yield to maturity. In this case, we already know that the present value of the bond is 144.99% at a .3% discount rate, so the yield to maturity must be .3%. If you buy the bond at 144.99% and hold it to maturity, you will earn a return of .3% per year.

Why is the yield to maturity less than the 6.00% coupon payment? Because you are paying €144.99 for a bond with a face value of only €100. You lose the difference of €44.99 if you hold the bond to maturity. On the other hand, you get eight annual cash payments of €6.00. (The immediate, current yield on your investment is 6.00/144.99 = .0414, or 4.14%.) The yield to maturity blends the return from the coupon payments with the declining value of the bond over its remaining life.

Let’s generalize. A bond, such as our OAT, that is priced above its face value is said to sell at a premium. Investors who buy a bond at a premium face a capital loss over the life of the bond, so the yield to maturity on these bonds is always less than the current yield. A bond that is priced below face value sells at a discount. Investors in discount bonds look forward to a capital gain over the life of the bond, so the yield to maturity on a discount bond is greater than the current yield.

The only general procedure for calculating the yield to maturity is trial and error. You guess at an interest rate and calculate the present value of the bond’s payments. If the present value is greater than the actual price, your discount rate must have been too low, and you need to try a higher rate. The more practical solution is to use a spreadsheet program or a specially programmed calculator to calculate the yield. At the end of this chapter, you will find a box that lists the Excel function for calculating yield to maturity plus several other useful functions for bond analysts.

2. Back to the United States: Semiannual Coupons and Bond Prices

Just like the French government, the U.S. Treasury raises money by regular auctions of new bond issues. Some of these issues do not mature for 20 or 30 years; others, known as notes, mature in 10 years or less. The Treasury also issues short-term debt maturing in a year or less. These short-term securities are known as Treasury bills. Treasury bonds, notes, and bills are traded in the fixed-income market.

Let’s look at an example of a U.S. government bond. In 1991, the Treasury issued 8.00% bonds maturing in 2021. These bonds are called “the 8s of 2021.” Treasury bonds and notes have face values of $1,000, so if you own the 8s of 2021, the Treasury will give you back $1,000 at maturity. You can also look forward to a regular coupon, but in contrast to our French bond, coupons on Treasury bonds and notes are paid semiannually.3 Thus, the 8s of 2021 provide a coupon payment of 8/2 = 4% of face value every six months.

You can’t buy Treasury bonds, notes, or bills on the stock exchange. They are traded by a network of bond dealers, who quote prices at which they are prepared to buy and sell. For example, suppose that you decide to buy the 8s of 2021. You phone a broker, who checks the current price on her screen. If you are happy to go ahead with the purchase, your broker contacts a bond dealer and the trade is done.

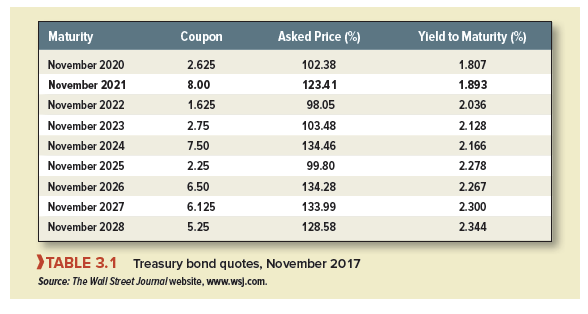

The prices at which you can buy or sell Treasury notes and bonds are shown each day in the financial press and on the web. In November 2017, there were 310 different Treasury notes and bonds. Table 3.1 shows the prices of just a small sample of them. Look at the entry for our 8.00s of 2021. The asked price, 123.41, is the price you need to pay to buy the bond from a dealer. This means that the 8.00% bond costs 123.41% of face value. The face value of the bond is $1,000, so each bond costs $1,234.10.[4]

The final column in the table shows the yield to maturity. Because interest is semiannual, annual yields on U.S. bonds are usually quoted as twice the semiannual yields. Thus, if you buy the 8.00% bond at the asked price and hold it to maturity, every six months you earn a return of 1.893/2 = .947%.

You can now repeat the present value calculations that we did for the French government bond. You just need to recognize that bonds in the U.S. have a face value of $1,000, that their coupons are paid semiannually, and that the quoted yield is a semiannually compounded rate.

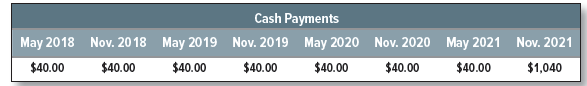

Here are the cash payments for the 8.00s of 2021:

If investors demand a return of .947% every six months, then the present value of these cash flows is

![]()

Each bond is worth $1,234.10, or 123.41% of face value.

Again we could turn the valuation around: Given the price, what’s the yield to maturity? Try it, and you’ll find (no surprise) that the semiannual rate of return that you can earn over the eight remaining half-year periods is .00947. Take care to remember that the yield is reported as an annual rate, calculated as 2 x .00947 = .01893, or 1.893%. If you see a reported yield to maturity of R%, you have to remember to use y = R/2% as the semiannual rate for discounting cash flows received every six months.

You could definitely see your skills in the paintings you write. The sector hopes for more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid to mention how they believe. Always follow your heart.